The Cathedral of Our Lady in Antwerp, a Gothic masterpiece that holds a Baroque treasure

The Cathedral of Our Lady of Antwerp is one of the symbols of the Belgian city: a masterpiece of Brabant Gothic, it holds a Baroque treasure inside (there are also four works by Rubens). It is also famous for having one of the tallest bell towers in Europe (the tallest in Belgium).

By Redazione | 07/05/2025 19:45

It is inside the Cathedral of Our Lady of Antwerp, located in the middle of the narrow streets of the Grote Markt, that some of Flanders' most important artistic treasures are to be found. And it is the Cathedral itself that is one of Belgium's most important monuments. Despite its bulk, moreover, the cathedral does not immediately offer itself to the eye in its entirety: the houses in the neighborhood almost jealously conceal it, leaving only the roofs and spire to soar unmistakably over the city skyline. This seemingly minor architectural detail tells much about the relationship between the city and its main place of worship: a relationship made up of pride, belonging, but also of a daily, almost discreet, coexistence.

The history of the Cathedral of Our Lady is rooted in the distant past. As early as the 9th century, a chapel dedicated to Our Lady stood on the present site. In 1124 the church, where some dissident secular canons lived, became a monastic church thanks to the work of Norbert of Xanten, who convinced some of the dissidents to found an abbey. The church became the new parish church of Antwerp and was transformed into a Romanesque church of considerable size (it was 80 meters long and 42 meters wide). However, it was not until 1352 that the ambitious project that would give rise to the current, spectacular Gothic building, destined to become the largest church in Flanders, took shape. Today, the church is 120 meters long and 75 meters wide, and reaches with the north tower a height of 123 meters.

The construction of the cathedral was a titanic undertaking, lasting nearly two centuries. The building site, which began with the choir and continued with the piedych and transept, saw the collaboration of local and French workers, under the leadership of architects Jan and Pieter Appelmans, and later Rombout II Keldermans. In 1518 the great north tower was completed, while the cross on the spire was consecrated soon after. The south tower, however, remained unfinished, stuck on the third level due to financial problems and the religious turmoil that would mark the city's history in the following decades.

The architecture of the cathedral reflects the complexity of Antwerp's social and political fabric. The two towers designed on the main facade were meant to symbolize the two great city powers: the civic and the religious. The north tower, financed by the City and the Corporations, also served the function of civic tower, while the south tower, borne by the parish, remained unfinished. This dualism, which remained visible in the asymmetrical silhouette of the facade, testifies to that tension between secular and spiritual authority that runs through the city's history.

At 123 meters high, the north tower is still the tallest bell tower in Belgium and one of the tallest in Europe, a record achieved after the destruction of St. Lambert's Cathedral in Liège in 1794. The tower also earned its inclusion on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1999, at the site "Bell Towers of Belgium and France." The bell tower contains a carillon of 47 bells, which punctuates city life with its melodies.

However, the Cathedral of Our Lady is not just a religious building, but an authentic site of the city's memories, as each century has left a tangible mark on the building: from the early Gothic structures of the 14th century to the Baroque and neo-Gothic additions, to the contemporary artworks that still enrich its spaces today. The cathedral has thus become a kind of living archive, where the history of the city and its community is layered and preserved.

Its history, however, was not without dramatic moments. In October 1533, a serious fire destroyed part of the building, forcing the suspension of extension work and the final abandonment of the completion of the south tower. In the following decades, the rise of Protestantism and the subsequent financial crisis of the Church made it impossible to resume the original plans. In 1559, Antwerp was elevated to a seat of diocese by the will of Philip II, but the cathedral lost and regained this title several times due to the political and religious events that swept through the city, from the Eighty Years' War to the Concordat of 1801 between Napoleon and Pope Pius VII.

The cathedral was then the scene of devastation during the Iconoclasm of 1566, when Protestants destroyed much of the interior decoration, and suffered further damage under Protestant administration between 1581 and 1585. Only with the return under Habsburg rule was it possible to begin slow reconstruction and restoration work, which continued throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Architecturally, the Cathedral of Our Lady represents one of the most significant examples of Brabant Gothic. The seven-aisle structure, divided by large bundled polystyle pillars without capitals, introduces an innovative conception of interior space, inspired by the Collegiate Church of St. Peter in Leuven. The transept, not much wider than the aisles, houses the high altar and a deep choir, whose ambulatory ends in an apse surrounded by five radial chapels. The brightness of the interior is provided by the octagonal lantern-tower, or tiburium, erected in the 16th century precisely to prevent enlargements from making the sacred space too dark.

Despite the spoliations it has undergone over the centuries, the cathedral still retains many valuable artistic relics. Inlaid in the black stone floor are tomb slabs inlaid with white marble, while at the entrance the visitor is greeted by a Carrara marble statue of the Madonna and Child, dating back to the 14th century, the work of the Master of the Marble Madonnas of the Meuse. The path inside the cathedral is punctuated by works of art that testify not only to the richness of the local artistic tradition, but also to the church's ability to renew itself and dialogue with the present. In the right aisle are the fourteen panels of the Stations of the Cross (1866), a stained-glass window with theLast Supper (1503) by Nicolaas Rombouts, and, in the chapel of the Venerable, a Rococo tabernacle in gilded copper, adorned with bas-reliefs of great refinement.

In the middle aisles, between the pillars, are paintings such as the Multiplication of the Loaves and Fishes by Ambrosius Francken (1598) and theLast Supper by Otto van Veen (1592), Rubens' master, one of the great masterpieces to be found in the Cathedral. In the left aisle, the chapel of Our Lady houses a wooden statue of Our Lady (16th century), that of Our Lady of Antwerp, which enjoys great devotion, while not far away is the tomb of Isabella of Bourbon (1478) and a Baroque marble and silver altar by Artus Quellinus.

The central pulpit, made of oak wood by Michel Van Der Voort in 1713, is an outstanding example of Baroque and Rococo sculpture. Coming from St. Bernard's Abbey in Hemiksem, it replaces one destroyed during the French Revolution. At the base, four female figures represent the continents, while the faces of Christ, Our Lady and St. Bernard appear on the parlor. Above it all, a veil held up by angels reveals the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove, while a heralding angel with a trumpet crowns the entire composition.

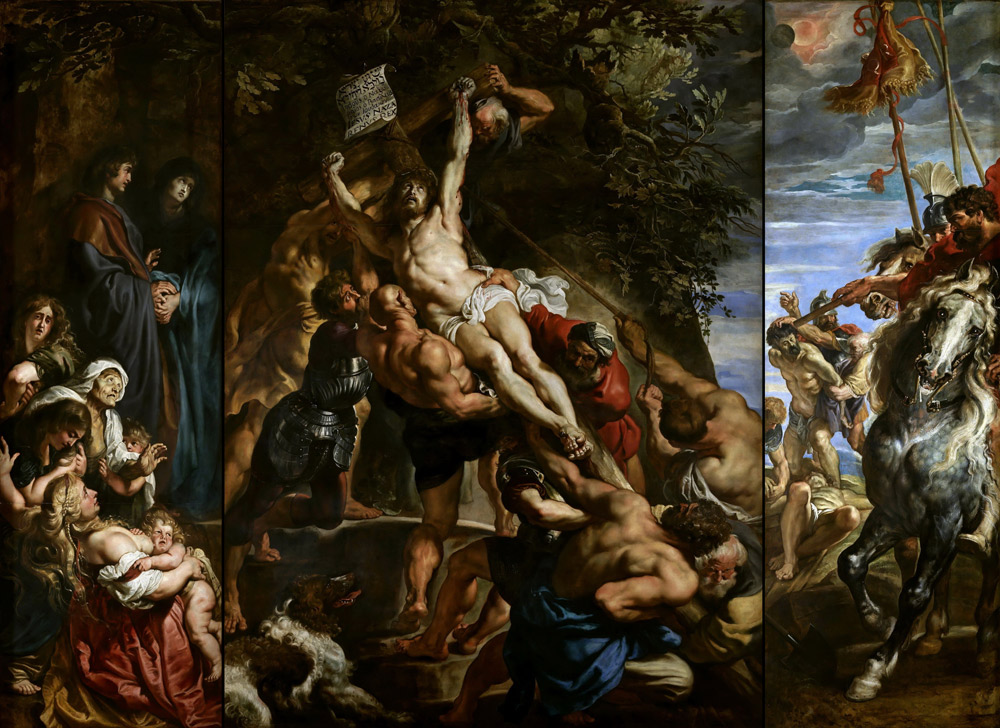

The Cathedral of Our Lady is most famous, however, for the presence of four masterpieces by Pieter Paul Rubens(more here), which mark an ideal path through the development of the artist's style. In the transept, the triptych of theElevation of the Cross (1610) introduces the Baroque to the Netherlands with its dramatic realism, while the Deposition of the Cross (1614), made only a few years later, stands out for its scenic construction and emotional depth. On the high altar, theAssumption of the Virgin (1626) represents a turning point in Marian iconography: Rubens captures Our Lady in the act of taking flight, surrounded by the apostles and the women who witnessed her death. In the chapel of Our Lady of Peace, the triptych of the Resurrection of Christ, painted for the tomb of Jan Moretus and Martina Plantijn, completes the journey through the different stages of Rubens' artistic maturation.

Alongside these historical works, the cathedral also hosts works by contemporary artists, such as Jan Fabre's self-portrait installation, The Man Carrying the Cross (2015), and Sam Dillemans'Homage to Rubens: the Descent from the Cross, which reinterprets the Flemish master's famous canvas in a modern key. These interventions testify to the vitality of the place, which is capable of welcoming and integrating different languages without losing its identity.

In addition to its religious function, the Cathedral of Our Lady has always been a landmark for the city community. Over the centuries, it has hosted public events, civil celebrations and moments of collective recollection, becoming a space for meeting and confrontation between different souls of the city. The cathedral has witnessed pivotal moments in Antwerp's history: from the devastation of the Wars of Religion and the French Revolution, which reduced it almost to ruins, to the major nineteenth- and twentieth-century restorations that restored its original beauty. Every intervention, every addition, every restoration has been the result of a dialogue between past and present, between memory and future.

Today, the cathedral continues to be a destination for pilgrimages, tourist visits and cultural initiatives, keeping alive the welcoming tradition that has characterized it for more than a thousand years. Its discreet but imposing presence in the heart of Antwerp is a tangible sign of a continuity that goes beyond human events, a silent reminder of the city's ability to endure, adapt and reinvent itself.