July 24, 1911: the rediscovery of Machu Picchu, the lost city of the Incas

At 2,430 meters in the Peruvian Andes, the Inca city was unearthed on July 24, 1911, by Hiram Bingham. Remained hidden for centuries after the Spanish conquest, Machu Picchu is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and a key witness to Andean civilization.

By Noemi Capoccia | 24/07/2025 15:31

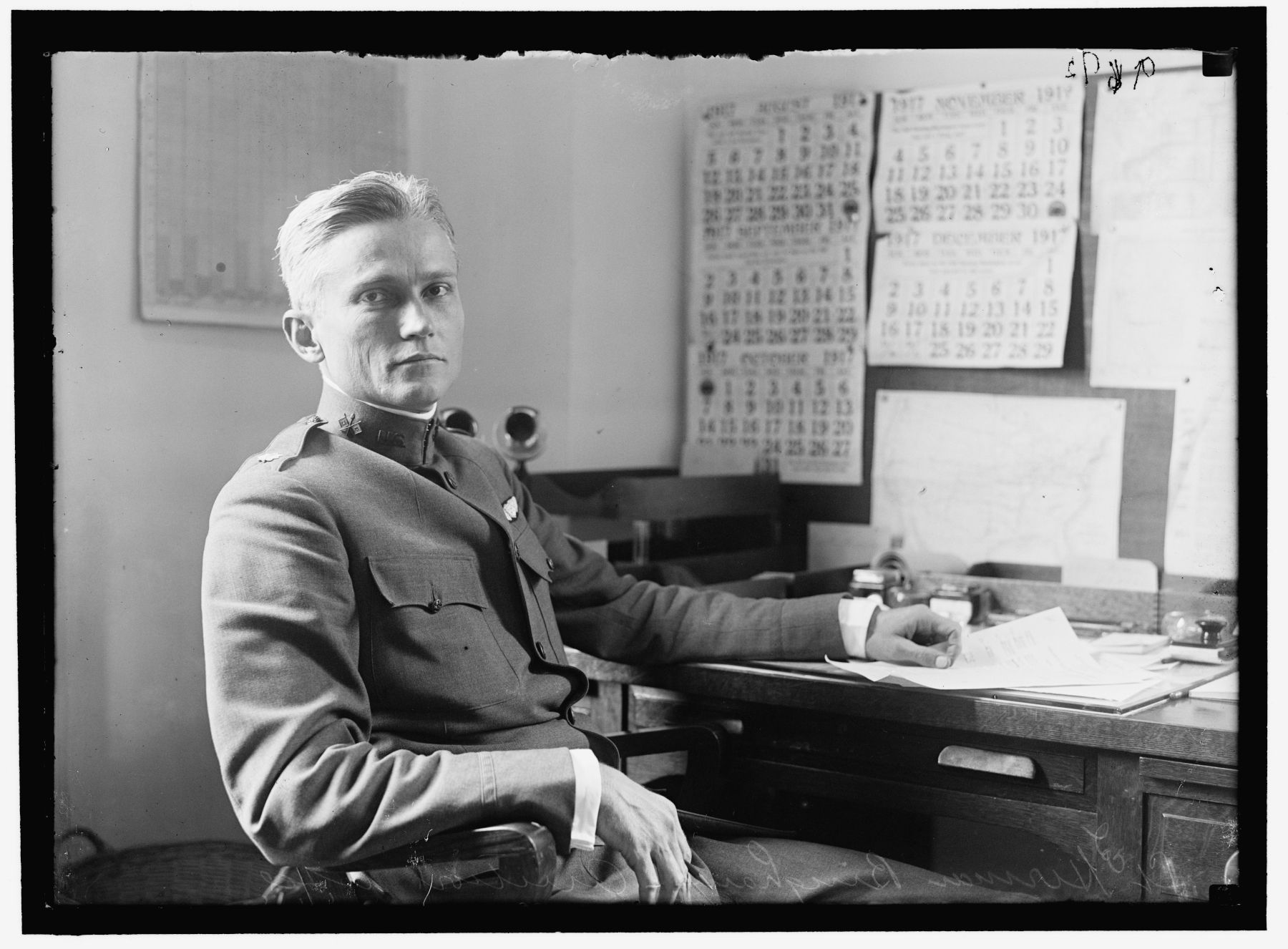

Majestic, millennia-old, shrouded in mystery, Machu Picchu was rediscovered in Peru on July 24, 1911 by U.S. historian and lecturer Hiram Bingham (Honolulu, 1875 - Washington, 1956). Indeed, the date symbolizes a crucial moment in the reconstruction of pre-Columbian Andean history. Situated at an altitude of 2,430 meters (7,500 feet) amid the peaks of the Peruvian Andes, the so-called Lost City of the Incas is now counted among the world's most important and spectacular archaeological sites, included since 1983 on theUNESCO World Heritage List. The discovery comes during a period, the first two decades of the twentieth century, characterized by a lively and intense exploratory activity that led to the rediscovery of numerous civilizations and forgotten places on the American continent. Among the most famous examples from those years is Percy Harrison Fawcett DSO (Torquay, 1867-deceased in Mato Grosso, 1925), a multifaceted figure who was a geographer, artillery officer, cartographer, archaeologist and explorer in the regions of British South America. Fawcett is best known for disappearing in 1925 with his eldest son Jack during an expedition to search for a lost city known as the City of Z, which he and others believed existed in the center of the Amazon rainforest.

The city of Machu Picchu, whose name in the Quechua language (one of the native American languages of South America) means old mountain, was most likely built in the second half of the 15th century, during the reign of the Inca emperor Pachacutec. The settlement, built in a strategically isolated location protected by deep cliffs, was abandoned less than a century later, around 1532, coinciding with the beginning of the Spanish Conquest. After its abandonment, the locality gradually disappeared from maps and the memory of the people. Nature absorbed its remains and the town entered the dimension of legend. No written sources from the colonial era mention its existence, and for more than four centuries its location remained unknown.

But how did the discovery of the lost city of the Incas come about? In December 1908, Hiram Bingham attended the first Pan American Scientific Congress in Santiago, Chile, where he had the opportunity to meet President Theodore Roosevelt (a strong bond was born between the two that would last until the former president's death). At the end of the congress, Bingham traveled to Peru, passing through Lima to Cusco, where he was welcomed by local authorities. His interest in exploration aroused enthusiasm, especially since it came from a U.S. delegate returning from an important scientific meeting.

So, after staying in and around Cusco, he ventured to Abancay in 1909, prompted by prefect Juan José Nuñez's desire to lead him to the archaeological site of Choquequirao, an Inca city located in southern Peru. Although he was neither an archaeologist nor a specialist in Inca culture, Bingham sought to document the site with photographs, surveys, and detailed descriptions, and during the exploration he read on the walls names and dates left by previous visitors, including Eugène de Sartiges in 1834 and José Benigno Samanez in 1861. His expedition, consisting of Nuñez and Lieutenant Cáceres, also left a trace, although in fact disappointment at the absence of tangible treasures prompted him to return to Lima and then to the United States.

The turning point came in 1910, when his friend Edward S. Harkness, after reading a draft of his book on the journey, suggested that he organize a new expedition to search for the last capital of the Inca, Vilcabamba. After several unsuccessful attempts to obtain funds, the project was financed by his wife Alfreda, the National Geographic Society and Yale University. In 1911, after lengthy preparations, Bingham then returned to Peru with a new expedition, and while gathering information in Cusco, the city's vice-prefect uttered a name destined to change his expedition: Huayna Picchu, the mountain at the base of which lay mysterious ruins known to few. Thus, on July 19 the expedition set out for the Urubamba valley, setting up camp a few days later on the Mandorpampa plateau near the site, which was also reported by the rector of the University of Cusco, Albert Giesecke.

On July 24, 1911, under a rainy dawn, Bingham entered the Machu Picchu archaeological complex for the first time. Before his eyes unfolded a city of exquisite architecture, built with impeccable Inca technique. Walls of white granite cut with extreme precision, temples, palaces, plazas and dwellings emerged from the vegetation that had hidden them for centuries. His discoveries included an inscription dated 1902 with the name Lizárraga, which showed that others had reached the site before him. In any case, it was Bingham who brought Machu Picchu to the world's attention.

In 1913, National Geographic magazine devoted a monographic issue to the discovery, igniting the interest of the international public. Bingham enthusiastically described the site, which in size and state of preservation was compared to the archaeological remains of Pompeii and Ostia Antica. The professor subsequently wrote several volumes on the site, the best known of which remains The Lost City of the Incas, published in the years following the expedition. Excavation campaigns were then conducted in two main phases: in 1912 and between 1914 and 1915. On those occasions, numerous artifacts were found, many of which were transported to Europe and the United States with the permission of Peruvian authorities at the time.

Hiram Bingham also came under criticism for the illicit transfer of a large quantity of archaeological artifacts: we are talking about more than 46,000 artifacts that were in fact taken and destined for Yale University. Of these, only three hundred were subsequently returned, while the remainder ended up in the collections of some of Europe's major museums, including the British Museum and the Louvre, or were dispersed in private collections. The issue of the return of the materials remained unresolved for decades until, some ninety years later, the Peruvian government entered into negotiations. We also know that an instrumental role was played by the then wife of the President of Peru, an archaeologist, who personally worked for the return of most of the artifacts to their place of origin.

In any case, the importance of Machu Picchu is not limited to the archaeological realm. The site represents an exemplary case of urban planning in a mountainous environment, with architectural, agricultural and religious structures perfectly integrated into the landscape. Among the best-known buildings are the Temple of the Sun, the Intihuatana stone, and the ceremonial area, which demonstrate the centrality of religion in Inca culture. According to historical tradition, Pachacutec, who led the empire's peak expansion phase, proclaimed himself the son of the god Inti, the solar deity, thus founding a dynasty of a theocratic nature. Indeed, the link between power and religion was one of the cornerstones of the Inca social organization, which succeeded in ruling a vast territory thanks in part to the ideological control exercised over the subjugated peoples. Machu Picchu, in this framework, may have had a dual function: summer seat of the imperial court and ceremonial site linked to solar worship. The arrival of the Spanish in the 16th century then marked the end of the Inca Empire. Colonial subjugation involved the dismantling of preexisting political structures and the imposition of Christianity as the official religion. Many ceremonial centers were destroyed or transformed. Machu Picchu, thanks to its isolation, remained intact even though abandoned.

Some interesting facts about the city

The site of Machu Picchu is built in a very seismically active area. Surprisingly, the stones of the most valuable buildings of the Inca Empire are not held together by mortar: they have been worked with such precision that they fit together perfectly. This system provides unsurpassed aesthetic beauty and also presents an important engineering function. Both Lima and Cusco, in fact, have been destroyed several times by strong earthquakes, and Machu Picchu lies just above two fault lines. During earthquakes, the stones dance, that is, they sway slightly and then fall back into place, thus preventing the buildings from collapsing. Without this technique, many of the most famous monuments would have long since disappeared.

For those who are not afraid of fatigue and altitude, it is possible to reach the ruins on foot, avoiding the high cost of transportation: the train ticket from Cusco exceeds 100 euros, entrance to the site is around 50 euros, and the bus ride up and down the slope costs another 20 euros. The walking trail, which takes about an hour and a half, in fact follows Bingham's route in 1911.

Another little-seen but crucial aspect concerns the engineering hidden beneath the surface. Although the Incas are best known for theircyclopean walls (similar to those of Mycenaean fortifications), their civil engineering proved highly advanced, if we consider that they used neither draft animals, iron tools, nor the wheel. Machu Picchu was in fact built by leveling a terrain between two mountain peaks, moving huge amounts of stones and earth to create a stable platform.

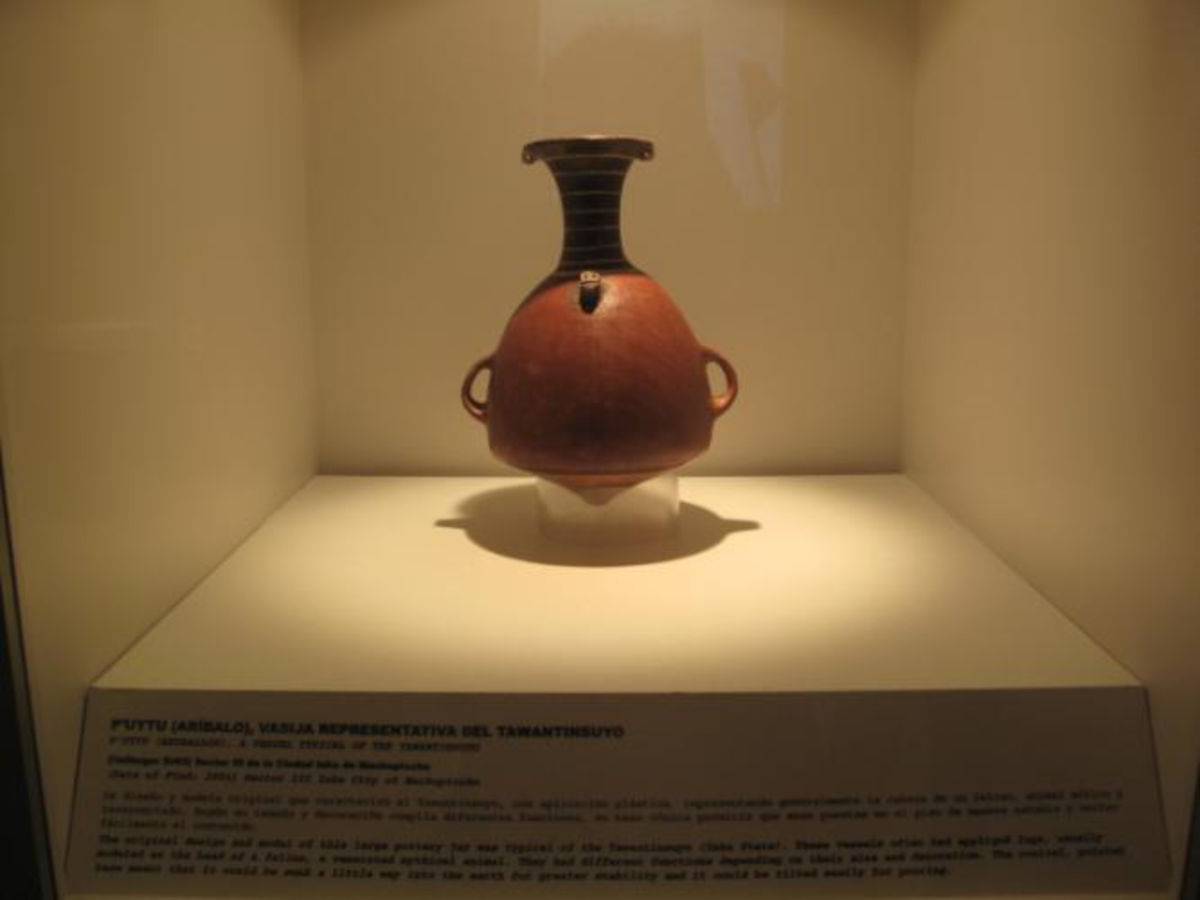

Finally, for those curious to explore further, there is a little-visited and somewhat hidden museum: it is the Museo de Sitio Manuel Chávez Ballón. Unlike the archaeological site, where contextual information is rather scarce, the museum provides a detailed overview in Spanish and English, explaining the historical and geographical reasons why the Incas built in that very area. Admission is inexpensive (about six euros) and presents a tour that guides the public through the main stages of the history of the Historic Sanctuary of Machu Picchu. The museum facility, which also presents the opportunity for a digital tour visitavirtual.cultura.pe, is named after Manuel Chávez Ballón, a researcher who promoted its creation in the late 1960s and early 1970s. After a period of closure due to renovations and exhibition upgrades, the museum was reopened on July 25, 2005, with a new museographic layout.

Five permanent rooms, distributed along an itinerary designed with an informative approach, tell the story of the cultural evolution of the area included today in the National Archaeological Park and Historic Sanctuary. Eight thematic sections, accompanied by visual materials, panels, maps, videos and infographics, take the visitor on a historical exploration that is completed by the display of numerous artifacts: ceramics, lithic tools, metal objects and archaeological evidence recovered during excavation campaigns.

What does Machu Picchu represent to date? An architectural and engineering masterpiece and a fundamental witness to the cultural and spiritual complexity of the Inca Empire. The rediscovery in 1911 opened a different page in the understanding of pre-Columbian history and highlighted the importance of preserving a heritage that embodies human ingenuity and the important the relationship between man and nature.