The tower of San Lazzaro in Livorno: the legacy of Mario Puccini in Labronica painting

A retiree with a vivid passion for his city, who put his savings toward a restoration: that of the tower of Livorno's ancient lazaretto. An act of love that gave back to all a precious asset, the protagonist of a fortunate iconographic production that has as its initiator the post-Macchiaiolo painter Mario Puccini.

By Jacopo Suggi | 19/08/2024 21:42

"A longing to embrace these walls, a desire to lean your face against them, and stand there like that, as if flesh could defend the stone and overcome time." Perhaps this expression left to us by José Saramago in his Journey to Portugal is among the most poignant and evocative passages of a relationship, almost symbiotic, between the individual and the bricks and rock that make up the vestiges of the past, which we now call cultural heritage. I have always thought that these words could have been quietly uttered by a Livorno retiree, Alberto Mazzoni, who shows no less love for the vestiges, admittedly little more than a pile of bricks, of a watchtower in the lazzeretto of San Leopoldo in Livorno.

Mazzoni's life has somehow been marked by the presence of those corroded stones, not only today that he is a frequent visitor to the beach where the tower stands, known as the "Scogli dell'Accademia," named after the Naval Academy that since the late 19th century has insisted on the spaces that were once the maritime health facility, but from an early age. Born in 1948, several episodes in his family history are linked to those bricks, so much so that he decided to allocate part of his savings from his metalworker's pension for the restoration of the tower, which had partly collapsed over time. But making his wish come true was not easy: Mazzoni in fact found many closed doors, until his request was advocated by the Committee "The Forgotten Jewel," which over the years had been campaigning for the recovery of important monuments such as the Crypt of San Jacopo and the Statue of Peter Leopold by Domenico Andrea Pelliccia. The committee's experience was instrumental in juggling bureaucracy, and eventually, in 2022, the restoration of the tower began, which, if it could not restore the structure to its original appearance by raising the collapsed top part, aimed to consolidate it to prevent future new collapses. But what makes this operation important is not so much the intimate and personal story of Alberto Mazzoni, but the possibility of having ensured the preservation of a trace of the past, and revived attention to those stones.

The tower of which virtually all memory had been lost, in fact, is valuable evidence of the fourth and last of the lazzeretti with which the city of Livorno was endowed, structures necessary to attempt to stem the plagues that spread through ships, crews, passengers and goods. Investigating the ancient plans, it becomes clear that the structure, in order to ensure isolation, was equipped with walls and protective towers, named after thaumaturgic saints or saints with ties to the locality, and among these appeared the tower of San Lazzaro, the one Mazzoni wanted to restore, the only one that was preserved after the bombings of World War II. As luck would have it, the structure that escaped the damage of the conflict is cloaked with an additional value, an iconographic importance that was carved out for it by the thriving cadre of artists of the Labronica school.

The initiator of this interest was probably the post-macchiaiolo master Mario Puccini. The Leghorn painter in his work had always opted for unusual iconography, as pointed out by Giorgio Mandalis in the catalog of the exhibition dedicated to the artist held in 2021 at the Museum of the City of Leghorn. Puccini, in fact, had always stayed away from the most characteristic views of the city, while curious is the attention the painter turned toward the lazzeretto, perhaps drawn to its geometries as a professor of technical drawing. Puccini evidently had a soft spot for the melancholy lazzeretto, a lonely, somber space marked by extreme silence, a vestige of a lost time, where the wall and towers give rise to solid, angular forms, whose warm rock gives unexpected chromatic effects, silhouetted against the skies of Livorno and lapped by the sea. Llewellyn Lloyd, another great Leghorn artist, in his memoirs titled Times Gone By, recalled the works Puccini created for Caffè Bardi, a historic artists' hangout active in the early decades of the 20th century. The Welsh-born painter noted that Puccini, for the café, produced "views of Livorno: seascapes with sailboats and barges, makes a grand scene of his beloved lazzeretto, showing off in large a synchrony of reds and blues that warms all the dark surroundings of the café with sunshine," and again in another passage, Lloyd speaks of this Puccinian infatuation: "He stops behind the Lazzaretto towards sunset, enchanted by the red brick walls, corroded and worn by the saltiness of the Medici fortress." This is a tangible sign of how Puccini's passion for the lazzeretto certainly should not have been a mystery to his contemporaries.

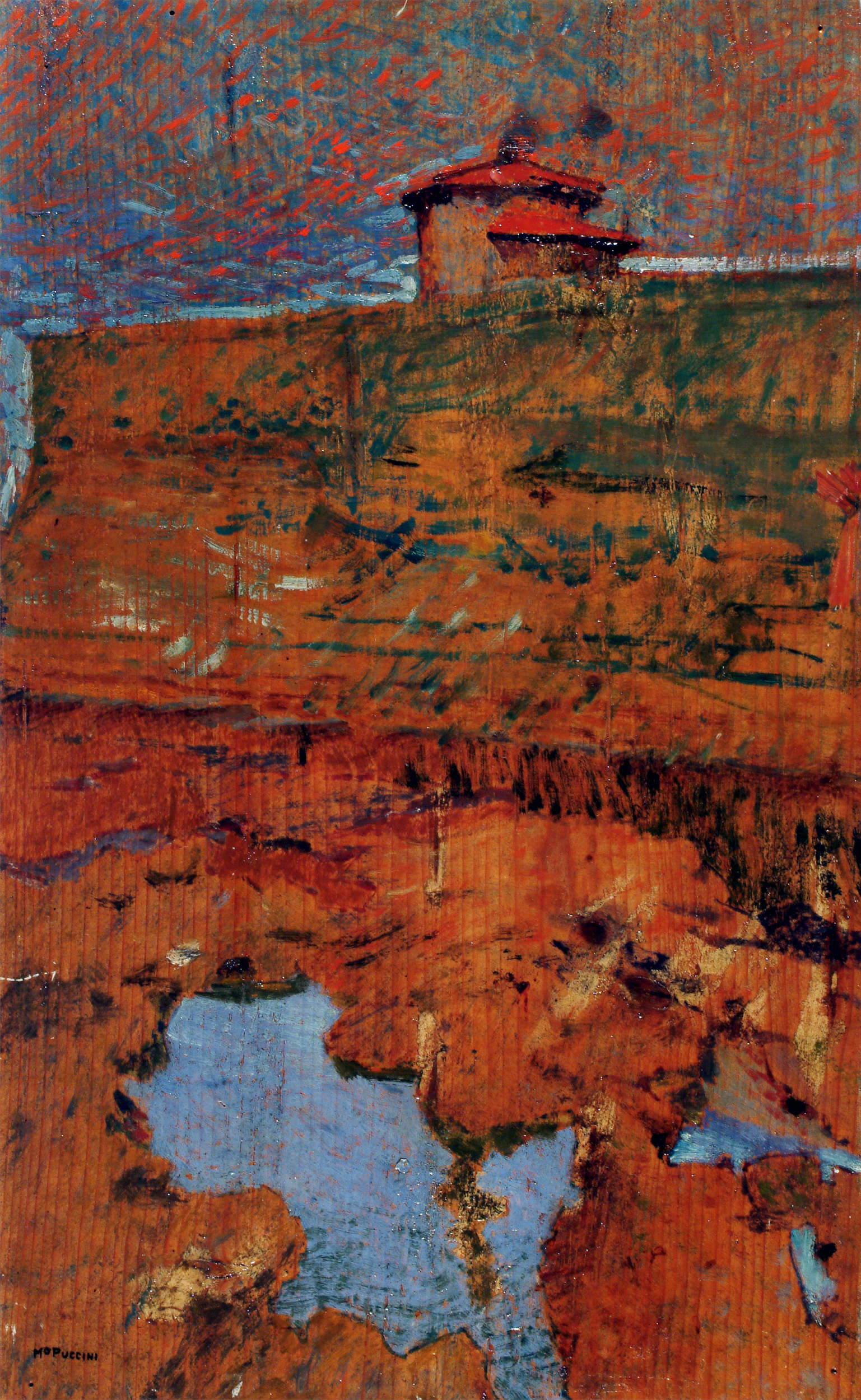

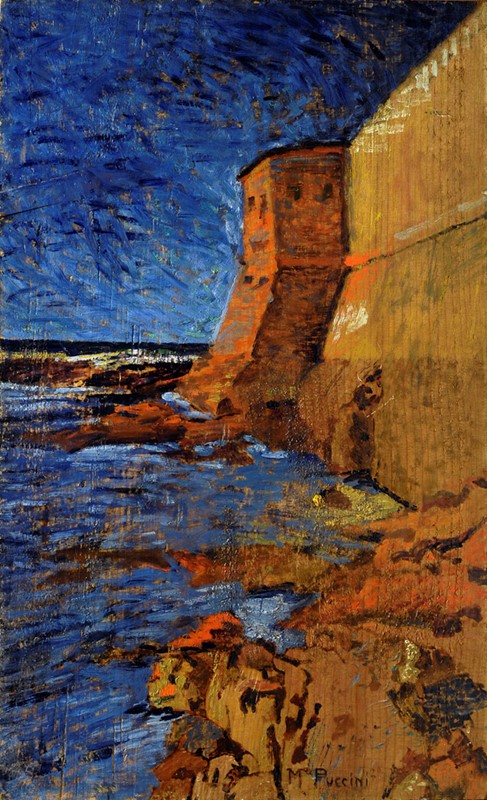

Probably the tablet titled The Lazzeretto of Livorno is the oldest one that has come down to us dedicated to the maritime health structure. Through a perspective typical of Puccini's, that is, with a bold foreshortening from below upward, the painter paints the low cliff jagged with red and brown tones, a texture interrupted only by the 'emergence of the bare board and a few pools of saline water; above it rises the imposing bulk of the lazaret wall, which goes to integrate by the chromatic solutions chosen, almost seamlessly, with the cliff. From behind the walls barely peeks out the summit part of the keep of San Rocco, the round tower placed to protect the entrance to the little harbor of the lazaretto, and just above it a small handkerchief of burning sky. To the same years is probably also to be traced a work with which it shares the palette and also a certain pictorial texture The wall of the ancient lazaretto of Livorno. The foreshortening presented is slightly varied: here the perspective is not barred by the massive wall, but rather it parades on the right side, then placing our very turret in the center of the composition. The composition is divided into two partitions, the one on the left where the clear blue of the sky meets that of the sea, and the red and brown tones of the turret and its respective wall that are integrated with the cliff on the lower right. The result is a less stuffy and pressed scheme than in the previous work, but more introspective and solitary.

Mario Puccini dedicated many other pieces to the lazzeretto, such as Scogliera del lazzeretto, Il lazzeretto dopo l'uragano, and Il mastio di San Rocco, but perhaps the most famous are the panels created for the Caffè Bardi. These are works of uncommon size for Puccini's production: Il Lazzeretto (Boat with fisherman seated from behind) and Il Lazzeretto (Boat with boy standing). We can therefore say with some certainty, unless works held in private collections in the future refute this thesis, that Puccini was the first among Leghorn artists to turn his attention to the lazzeretto and certainly the one who set the most paintings there.

The Leghorn master, who died prematurely in 1920, was elected as the point of reference for an entire generation of artists, who saw in him the continuer of the tradition begun by Giovanni Fattori. In the very year of his death, the Labronico Group was formed in his honor, which initially should have been called the "Mario Puccini" group. Puccini's death also witnessed a new critical analysis of the artist: an article by the powerful critic Ugo Ojetti aimed at exalting the figure of the artist was published in the "Corriere della Sera"; and then several of his works appeared in various exhibitions, including the 1922 Venice Biennale. This new exhibition fortune that invested Puccini's production, together with the role that Leghorn culture was carving out for him in the local pictorial legacy, probably prompted more and more artists to measure themselves against the subject of the lazzeretto.

But of all the iconographies indicated by Mario Puccini, it would seem that one in particular has entered the cultural carrier of more than one generation (moreover, the one with which Puccini was confronted with only one piece): it is the turret of San Lazzaro, which, eternalized in the painting Il muraglione dell'antico Lazzeretto in Livorno, would have been painted several times by Livorno painters, preferring it instead to the more characteristic keep of San Rocco. What is the reason for this iconographic success we can only speculate. A choice perhaps dictated not only by orientations of taste, but also by purely practical reasons. Of all the views of the harbor health structure only Il muraglione dell'antico Lazzeretto in Livorno would have had any prominence in the years immediately following Puccini's death. In fact, the painting was exhibited in 1922 in the V Mostra del Gruppo Labronico and in 1930 in the Centenary Exhibition of the Società Amatori e Cultori di Belle Arti held in Rome. In addition, precisely in conjunction with the Gruppo Labronico exhibition, the work also rose to prominence in the print media thanks to the interest of Campania critic and man of letters Gino Saviotti, who wrote about it several times in "Il Telegrafo" and the magazine "Pagine Critiche." A few years later, in 1931, Mario Tinti also included the work in his publication dedicated to Puccini. In a short time then, more and more artists pushed themselves to confront this emblematic work by the great painter.

There is an endless number of works dedicated to the same subject by even very different artists, more faithful interpretations alternating with more original works, good paintings and stereotypical reproductions. Among the oldest is perhaps that of Gino Romiti, who painted the lazzeretto in 1925. In the tiny space provided by the tablet, Romiti replicates the foreshortened view of the San Lazzaro turret, preferring Puccini's usual perspective. The result is a painting that is less expressive and laden with ominous foreboding, with no unexpected coloristic suggestions to give it a more earthy reading, closer to a simplified Factorian verbiage of which Romiti had been a pupil, and of which he had become one of the greatest interpreters.

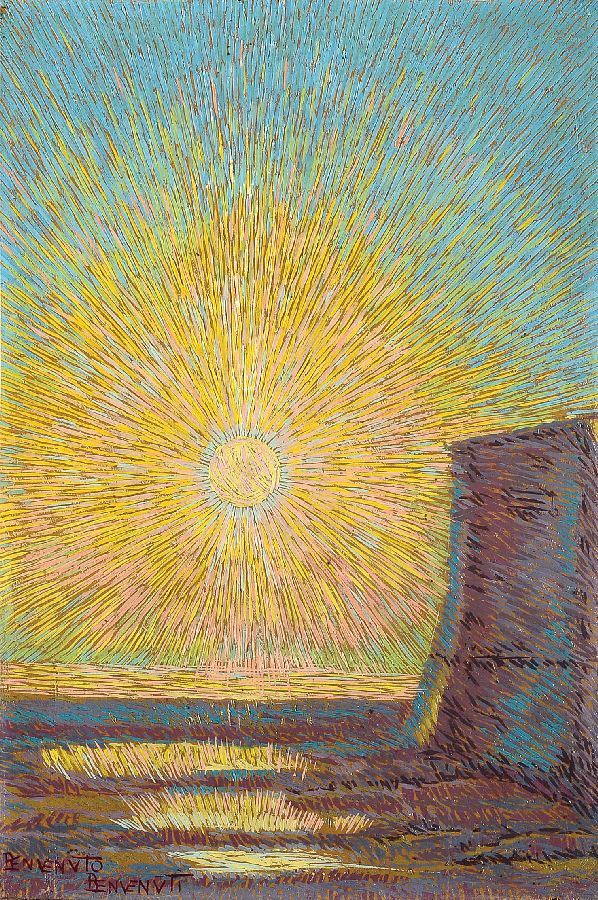

Divisionist Benvenuto Benvenuti also confronts Puccini's legacy, in the operas Tramonto and Notte al lazzeretto. In the nocturne composition, the one most faithful to the primitive model, he sets his work in a gray night interspersed with small blue filamentary brushstrokes of a Divisionist matrix, while the stones that make up the turret and the wall are scratched by a tangle of multicolored graphic signs also found in the rocks. The second, modestly sized tablet, on the other hand, shows the tower, whose architecture is simplified, captured when the now waning sun is perfectly in axis with it. The fiery star is the center of the composition, and glowing, textural rays originate from it, imposing rhythm on the entire composition.

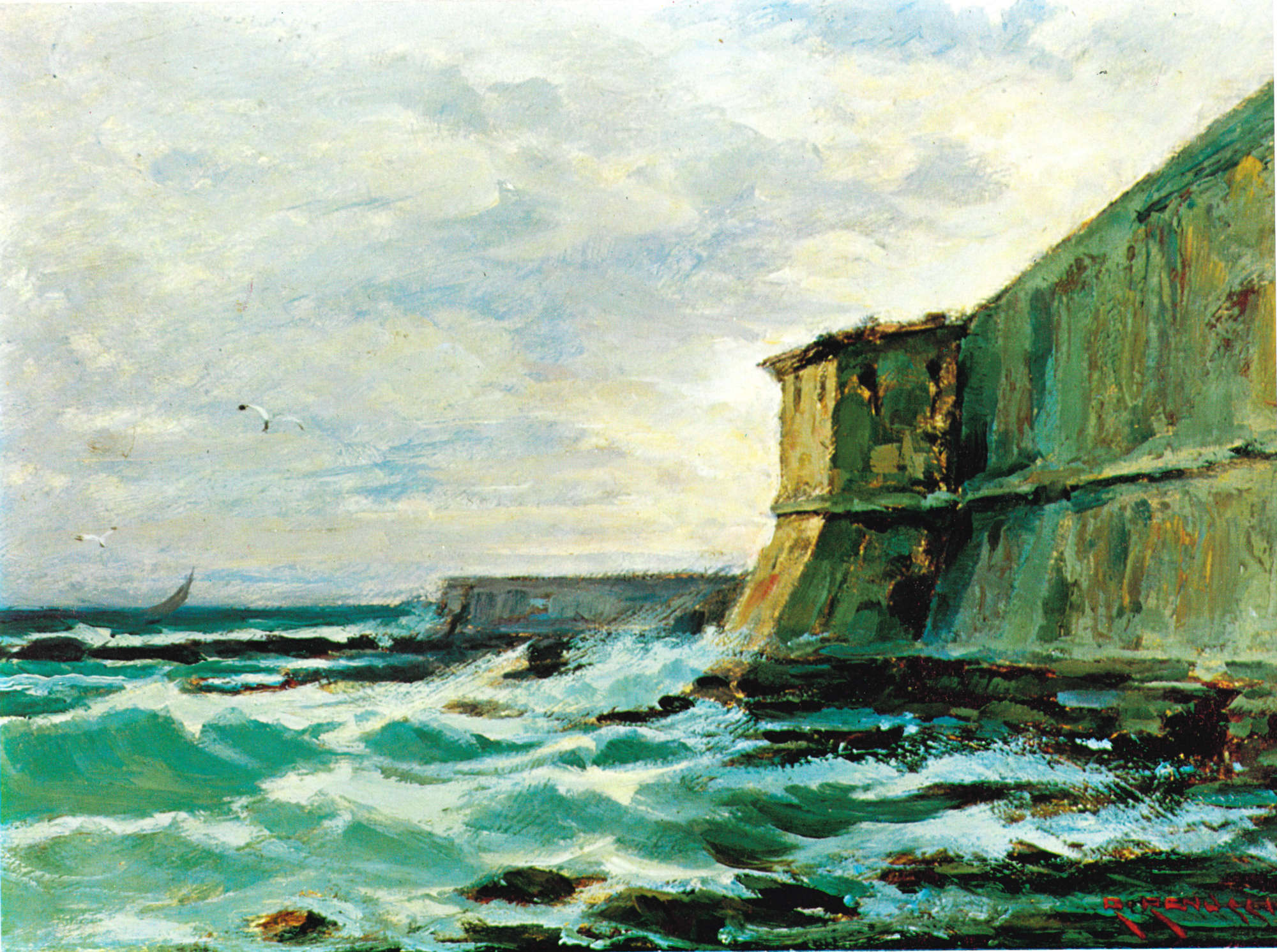

The painter Renuccio Renucci repeatedly reiterated paintings with views of the lazzeretto and in particular of the tower of San Lazzaro, in compositions that were sometimes larger, others smaller. We know of at least six works with the same subject, yet never repetitive: Renucci captures the tower at different times of the day, at dusk, at sunset and at night, but also in different weather conditions, crystal clear days alternating with cloud-laden nights or afternoons where the wind rages the sea. With great talent, the artist adapts the pictorial register with the changing temperament of the painting.

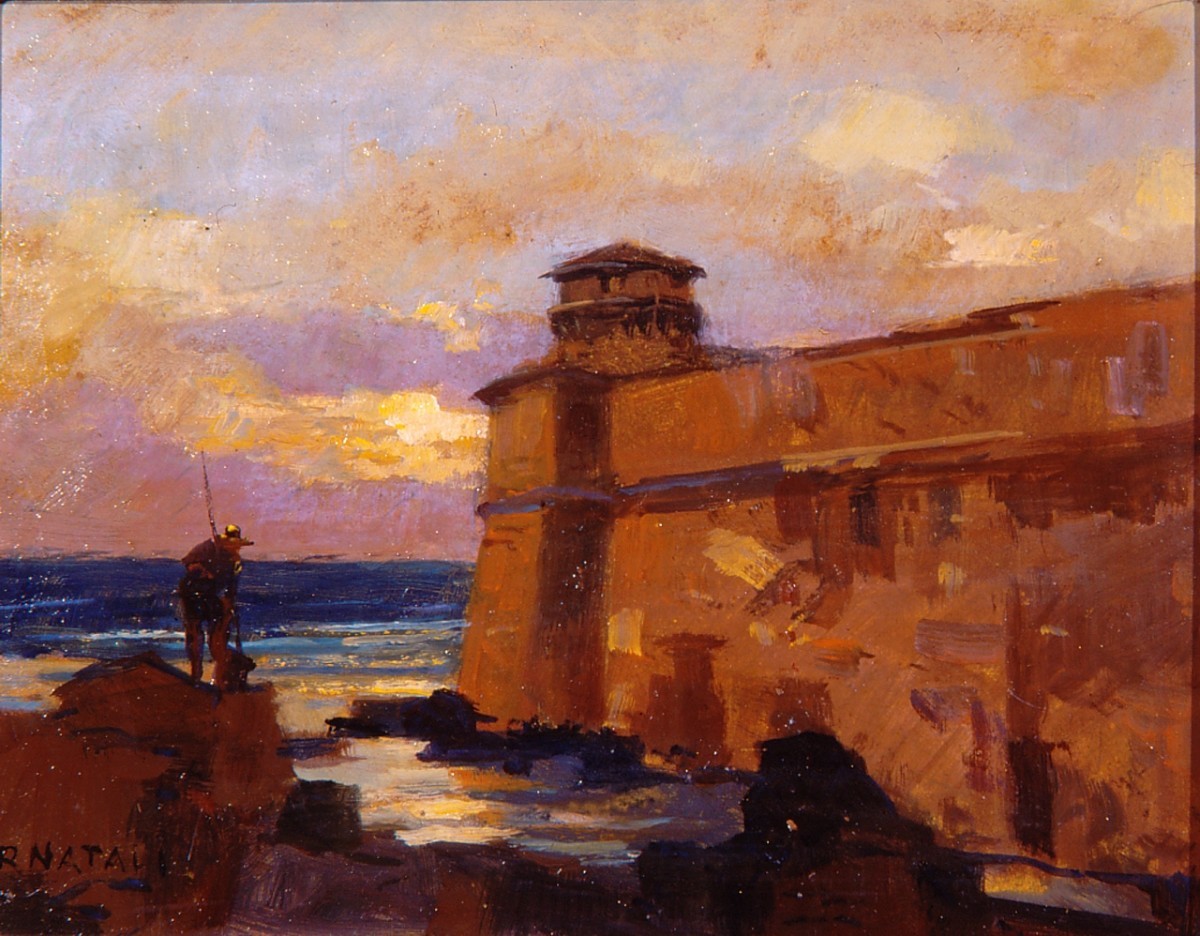

Renato Natali, among all Leghorners the one who with more commitment outlined an urban iconography of Leghorn, particularly the one that disappeared and was erased by bombs and reconstruction, did not fail to confront the theme of the lazaretto. The large group of works with that subject shows the same and rather monotonous patterns to which the painter returned several times over the years, albeit alternating horizontal and vertical supports. Natali creates views not from life, but rather mental reworkings by offering depictions that do not strictly adhere to the real thing, making changes to the original architecture. Decidedly more innovative, however, is the view of the lazzeretto handed down to us by painter Giovanni March in the work Marina, painted around 1960 and recently exhibited in the exhibition Giovanni March, The Painter of Light and Atmosphere curated by Michele Pierleoni. March, in a piece of great tonal painting, offers an almost intimate synthesis of the landscape. The certainly lesser-known Gino Centoni gives a more rambling and pastel reading of the turret, stripped of all anecdotal detail, while Carlo Domenici returns to models more in keeping with a late naturalism.

The artists of later generations were not exempt from the fascination with the subject of the San Lazzaro turret, and although perhaps the confrontation with this Puccinian iconography lost those characters of systematicity that the artists of the first Labronian Group had paid tribute to it, it had nonetheless been assimilated into the heritage of images and views of the Labronian pictorial tradition. In the second half of the twentieth century up to the present day, some painters have continued and still continue to deal with the foreshortening bequeathed by Puccini. It is difficult, however, to determine whether the will and awareness to pay homage to the old master's tradition with this pictorial foreshortening is also present in later artistic generations, or whether the choice is not due to the fact that the veduta has now entered the common imagination. Among them are painters of even very different qualities, but united by a very local penchant for figurative landscape painting, including Masaniello Luschi, Millus (Pietro Illusi), Giovanni Meroli, Aldo Mazziand Mario Rombolini, and Piero Vaccari.

Of some interest are those left to us by Giorgio Luxardo, which also record the passage of time, unlike the still landscape so far analyzed in the works of the other painters. His warm-colored paintings show us the tower of San Lazzaro now stumped, with the landslide end as it stands today. In Luxardo, the much larger composition no longer places the focus on the architectural bulk of the turret and the walls, but they become part of the background of picturesque seascapes, where scenes of seaside life are set. It is no coincidence that even the name by which these works are known no longer bears reference to the lazzeretto and its tower, but instead to the toponym by which this place is known and frequented by bathers today, namely "cliff (or rocks) of the Academy." These are just some of the passages identified starring the tower of San Lazzaro, and published in the writer's book entitled La Torretta di San Lazzaro. The Lazzeretto of San Leopoldo in Leghorn Painting.

Finally, wishing to draw a parallel that seems fitting to us, the tower of San Lazzaro stands to Puccini as the splendid tamarisk of Antignano eternalized by Giovanni Fattori in the painting la Libecciata stands to the progenitor of Leghorn painting. Both were masters and references for entire generations of artists, both linked their legacies (at least in the local sphere) to these respective views, views that were then widely successful, until they became acquired images of an indigenous tradition.

Why then both subjects had luck as pictorial testaments of the two masters, we can only speculate, but in this regard the words used by Federico Giannini, editor of this newspaper, in an article devoted to Libecciata, where he writes: "A landscape, then, which is alive as a portrait. Or perhaps, like a self-portrait." Here I believe that a not dissimilar speech can also be spent on Il Muraglione del Lazzeretto, a painting by Mario Puccini and the tower of San Lazzaro that is its main subject. At the end of this certainly not brief digression on the turret, one will then understand the importance of having safeguarded that pile of bricks, which when properly read show themselves in their value as an important testimony of the past and a monument made iconic by the painting that artists have recorded in different epochs and different light and climatic conditions. Here, I believe that perhaps the ideal approach to not losing all this is to follow that path already indicated by Tomaso Montanari, when about cultural heritage he writes to "look at the stones and see not the stones but the people."