In Lunigiana, inside churches that hide traces of the struggles between Christians and pagans

In Filattiera, Lunigiana, two houses of worship hide the traces of a very ancient struggle: that of the Christians who, between the 6th and 7th centuries, tried to eradicate pagan idolatry among these mountains. A fascinating and largely unknown story, hidden within the walls of the oratory of San Giorgio and the parish church of Sorano. With two stele statues to pass it on.

By Federico Giannini | 01/09/2024 16:00

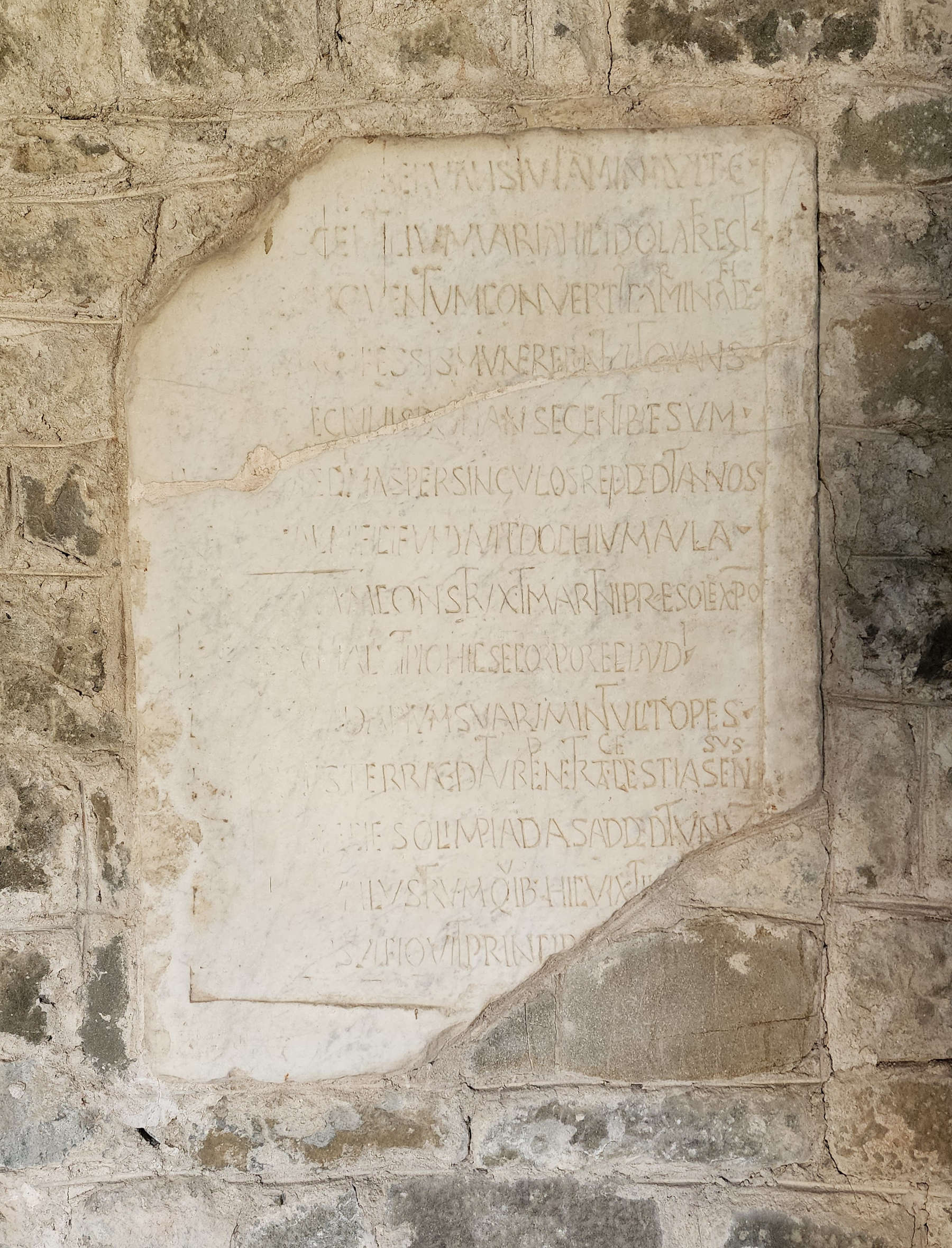

Bare, severe, devoid of any ornamentation. The small church of San Giorgio that stands in the lower part of the charming Filattiera, in Lunigiana, is a large pile of squared ashlars, a heap of stones that shortly after the year 1000 were stacked on top of a terrace to give a house of worship to the inhabitants of the village. Inside there are no painted panels, no fresco cycles, no fine furnishings, no nothing. One does not enter the Oratory of St. George to see works of art: if anything, if one decides to step through its small, massive stone portal, it is out of pure curiosity. Or, at most, to try to understand what the religious sentiment was in those far-off times. And in that sense it is a small Romanesque church like many. There is, however, one element that distinguishes it from all the others. A unique element. It is a marble slab that is walled in one of its walls, we do not know how long ago and we do not even know why: we only know that it is one of the most relevant testimonies of early medieval Italy. She is what makes this church so interesting: a slab that is the keeper of the oldest secrets of the lands of Lunigiana. A marble trace that tries to light a faint lamp in the darkness of history. Fourteen lines in Latin that hand down the memory of a time when Christians struggled to convert the last Lunensi refractory to the Gospel. And, apparently, they finally succeeded.

They call it the "Leodegar Gravestone," because in 1910 a local scholar, Pietro Ferrari, first read this name on the plaster on the side of the slab. Leodegar, perhaps Leodgar, in Italian Leotecario: in fact, the name on the wall may not even be referring to the epigraph. And on this point almost all scholars now agree, but the tombstone continues to be called by its conventional name. We do not know then what the real name of the person whose story the slab tells is. Nor do we know where it was originally placed, although it is evident that it covered a tomb, the tomb of an eminent personage: the signs of wear are typical of a marble that has been trodden on for centuries. Perhaps it was inside the parish church of Santo Stefano in Sorano, at the bottom of the Magra valley, the most fascinating Romanesque parish church in Lunigiana. All we know is that the history of this tombstone takes us back in time. To the time when priests and bishops were busy trying to indoctrinate the pagans still remaining in these areas, "not without contrasts," writes scholar Enrico Giannichedda. Pagans perhaps in the literal sense of the term: the inhabitants of the pagi, the most remote villages, hidden in the middle of the woods, among the mountains, hours' walk from the settlements closest to the communication routes. It takes us back, if we want to be precise, thirteen centuries. To the fourth year of Astolfo's reign. This is the date engraved on the slab, the year in which Leodgar died. The year 752 AD.

At that time, Lunigiana was the territory of the Diocese of Luni, founded probably three hundred years earlier, roughly: strong was the presence of Christians in the territory of Lunigiana and relevant must have been their community, since it is attested that the bishops of Luni had taken part, several times, in Roman synods between the fifth and sixth centuries. A presence, however, not so pervasive as to have culled all idol worshipers. We do not know who they were: perhaps stubborn pagans, mountain people who did not want to know about Christs and Madonnas, indomitable gentiles who lived in the most remote and inaccessible areas of Lunigiana. Perhaps people who did not want to be persuaded to embrace that Christianity to which even the Romans had converted, elevating it with Theodosius to the sole official religion of the empire in the year 380, with the Edict of Thessalonica. Eleven years later, pagan cults would even be banned. In Lunigiana, however, there were those who offered some form of resistance to Christianity, so much so that in 599 Pope Gregory the Great wrote to Venantius, bishop of Luni, to point out to him that it would be appropriate to consecrate new priests to turn the inhabitants of these mountains away from idolatry, to counteract the pagan cults still widespread in his land. We have little idea what these cults were: it is a fact that the Leodegar of the slab had found himself fighting them during his work of evangelization of Lunigiana. In those fourteen lines written in Latin on marble lies the summary of his life, the life of a man who knew nothing but total devotion to his creed. A summary that begins like this, "Not caring about the danger of death, he had broken pagan idols, converted sinners, helped the needy, fed pilgrims with his bread, distributed the tithes collected every year, founded the hospital of St. Benedict with its chapel, built a church dedicated to St. Martin." It is a portrait of a tireless missionary, a preacher devoted to action, a man who clearly also had broad decision-making powers, so much so that it was thought that the Leodegar on the plaque was the Leothecarius bishop of Luni who lived between the seventh and eighth centuries and is mentioned in the Acta sanctorum. And it was thought that he must have been buried not in the church of San Giorgio, but further downstream: in the parish church of Santo Stefano in Sorano.

Here, still in the seventh century, there was a Byzantine settlement, a fort called "Kastron Soreon," which stood on the plain of the Magra, the valley that today is crossed by the state road that runs the length of Lunigiana, starting from Sarzana and reaching as far as the Cisa and then continuing on to the Po Valley. It was the most important Byzantine military base north of Luni. That this area was a Byzantine garrison is, however, also evident from the very name of Filattiera (derived from the Greek Phylakterion, "fortress"), and from the fact that the titular saint of the village church, George, was the patron saint of the Byzantine army. The defensive system of the Provincia Maritima Italorum, the name the Byzantines gave to Liguria after conquering it in 538 during the Gothic War, which would end fifteen years later with the Byzantines' victory over the Ostrogoths, passed through here. They managed to hold it for just over a hundred years: as early as 643 the Lombard king Rotari finished his work of conquering Byzantine Liguria. Perhaps, however, an early house of worship had already been built when the Byzantines arrived. And it was also the one in which, in Lombard times, perhaps Leodegar was buried.

Later, between the 11th and 12th centuries, the old early medieval oratory was replaced with the present parish church: it was to become one of the most important buildings of worship in the Diocese of Luni. It was entirely built with river stones: the Lunigiana is a land abundant with water, with rivers, rivulets, streams. And it was not difficult to procure the raw material. Pebbles smoothed by water, all of different shapes and sizes, bound together with thick layers of mortar to form a basilica-shaped pieve: three wide, austere naves, without a transept, with a raised presbytery, preceded by a tripartite, salient façade, in the middle of which opens a four-lobed rose window reminiscent of the shape of a cross, which, however, could be the result of an intervention much later than the time when the parish was built. On the contrary, it is evident that the facade was remodeled over and over again, so much so that what is preserved of the original facade is only a portion of what can be seen: according to Giannichedda, it can all be reduced to "a secondary door, part of the central arched portal, perhaps a small window, large sections of the masonry preserved in height for about two meters and on which the later phases were set." We speak, moreover, of a parish church with rich stratification. To the side, a square, tall, squat bell tower with large, arched, walled-in windows: perhaps it originated as a watchtower and was later retrofitted. Behind, here are the three apses, also made of river stones, softened by large blind arcades, some decorated with lozenges. Also above is a small, unusual bell gable, not so common to find on an apse. All covered with large slabs of slate.

Even the parish church of Sorano inside is unadorned. Imposing, sober, grave. But here, too, there is something that breaks the balance: immediately after entering, one cannot help but notice the two stele statues that were put here between the 1990s and the early 2000s. A presence that seems jarring: a medieval church with two pagan idols inside? Modern ideas. Yet, those two statues almost seem to want to escort anyone who enters the church, they seem to want to play their role to the full as resigned witnesses of the history of a land inhabited in ancient times by a tough and proud people, who knew how to stand up to the Romans and did not want to give up the worship of their deities. Perhaps not even after the empire collapsed: the Apuan Ligurians were long gone, but the inhabitants of Lunigiana perhaps continued to revere those statues that were forgotten for centuries and were rediscovered only in the nineteenth century, a time when the first known stele statue was found in Novà di Zignago, in Val di Vara, not far from here. And here, in Sorano, seven stele statues have been found, a sign that in this area of the Magra valley, just a few meters from the great river, there must have been an important cult area. The first statue ever found in Sorano is here, inside the parish church: it is a female stele found in the 1920s, two and a half meters below the floor of the church. She was face down, headless, with signs of deliberate damage: someone, centuries ago, removed her breasts, surely because that statue served as a building material, it had to fit into the wall of a tub, and then it had to be made smooth. Then, when the tub was no longer needed and was dismantled, the statue was buried. The second stelae statue inside the parish church is "Sorano V": the stelae statues are given the names of the place where it was found, followed by a progressive Roman number indicating the chronological order of its discovery. It is better preserved than its smaller sister: meanwhile, its head is intact, is almost round, and does not have the half-moon shape that is commonly associated with stele statues, because it was reworked at a later date, more than a thousand years after it was made, most likely at a time in history when the Apuan Ligurians had perhaps begun to have contact with the Etruscans and were trying to give their idols more realistic features. We clearly recognize that he is a man and that he carries several weapons (an axe in his left hand, two javelins in his right, a dagger attached to his belt), so that today this statue is known to all as "the Warrior of Sorano." His weapons, however, could do nothing against Leodegar's shepherding and the forced Christianization of the inhabitants of these valleys.

Perhaps it is precisely to the stele statues that the tombstone of San Giorgio refers when it speaks of "broken idols." These mysterious statues, symbols of the ancient cults of the Apuan Ligurians, witnesses to their culture, their openness, their way of life, were either systematically destroyed during the early Middle Ages or reused. The Sorano Warrior himself had an inglorious end: he became the lintel of one of the parish doors, with the carved part facing upward, so that he was unrecognizable. And so it remained until July 1999, when the Warrior was discovered and removed from that location that had stripped it of all dignity: today, therefore, it is there, at the entrance to the parish, ready to tell its story to anyone who cares to hear it.

By the time Leodegar was roaming around Lunigiana preaching his god, converting pagans, coming to the aid of the needy, and founding churches and hospitals, there were few stele statues still around. Most of these ancient monuments had already gone underground. Some, however, still remained proudly and stubbornly visible, and even if their ancient worshippers no longer existed, it is possible, wrote Michele Armanini, one of the foremost scholars of the Apuan Ligurians, that "still in the early medieval period part of the population of Lunigiana practiced a cult linked to these artifacts." Even according to medieval art historian Guido Tigler, Leodegar's "broken idols" are nothing more than the stele statues of the Apuan Ligurians. Fetishes to be torn down. Or, at best, to be incorporated. To be reused as building materials, taking care that no one could see them anymore, that they could understand what they were, making sure that not the slightest trace remained of those cults and their totems.

Of course, about the "broken idols" the most varied hypotheses were then formulated. There are those who believed little in the idea of a survival of pre-Roman forms of worship in the late antique period, and explained the story told by the tombstone on the basis of some form of idolatry practiced by the Lombards (so thought Ubaldo Mazzini, who recalled a cult of trees and one of fountains), or, Romolo Formentini and Sandro Santini hypothesized, by the Goth mercenaries who served in the Byzantine castrum and who were a source of concern for the local populations. In any case, it is certain that the evangelizers of these lands wanted to get rid of any remnants, whether the inhabitants wanted them to or not. The history of the Apuan Ligurians thus remained buried for centuries, until the findings of the nineteenth century. And that there was a significant area of worship in Sorano, where the parish now stands, was discovered in even more recent times. So here was the idea of placing the stele statues inside the church, inside the temple of those who had wanted them erased. A kind of reparation, if you will. The statues that had been used as walls and lintels return to their place, to make evident to all the nature of this place, sacred for the Apuan Ligurians first, for the Romans later, for the Christians in the end. A kind of continuity, despite everything. A continuity that has transcended the ages, and that lives on today in those two statues. It could be said that they have little to do with the church, that in ancient times no one would have put them inside the parish, and what is more at the entrance. It only takes a little, however, to break down any security: go to the center of the nave looking at the altar, and look up to the left. You will notice a relief. Very familiar-looking. Its chronology is not yet clear, nor do we know what exactly it depicts or what it means. Probably an apotropaic figure, or an allegory of something. Whatever it means, one will notice a striking resemblance to the stele statues: it is clear that whoever carved that relief had those very ancient pagan idols well in mind. Yes, they had been broken. But somehow they had continued to survive.