Ceramic Treasures. The extraordinary spread of robbiane in the Valtiberina.

The glazed pottery technique promoted by the Della Robbia Renaissance workshop had a widespread fortune in the Valtiberina, where they can still be admired throughout the area. An itinerary to discover the robbiane of the Valtiberina.

By Jacopo Suggi | 04/09/2024 02:30

Along the banks of the upper Tiber River lies the Valtiberina, a land known for its splendid landscapes but also for its contribution to art. Here, in fact, were born Michelangelo and Piero della Francesca, who also left some of his most significant works there. The valley was also the site of the famous battle of Anghiari, made eternal by Leonardo da Vinci's late masterpiece. This area is endowed with a rich artistic heritage, of which a notable reason for interest is covered by the splendid robbiane scattered among churches and ancient palaces; these are the famous glazed ceramic sculptures that were popularized by the Florentine Della Robbia family and some close followers between the 15th and 16th centuries.

"Luca therefore, passing from one work to another, and from marble to bronze and from bronze to earth, this he did not out of infingardiness, nor for being, as many are, fantastic, unstable and not content with his art, but because he felt himself pulled by nature to new things, and by need to an exercise according to his taste and of manco fatigue and more gain. Hence the world and the arts of drawing were enriched with a new, useful and beautiful art, and he with immortal and perpetual glory and praise": thus concluded Giorgio Vasari 's life of Luca Della Robbia (Florence, c. 1400 - 1482), the progenitor and inventor of a technique that still, a century after its introduction, enjoyed great consideration and success. The Florentine sculptor was born around 1400, and distinguished himself in the early decades of his activity with gold work and marble sculpture, including the Cantoria for Florence Cathedral executed between 1431 and 1438, and the five panels dedicated to the Liberal Arts for Giotto's Campanile; he began experimenting around the 1940s with this new application for sculpture. As revolutionary as the scope of Della Robbia's work was in Italian art, one must nevertheless downplay the hagiography that Vasari weaves about it: in fact, Luca had not invented the technique per se, but had adopted ancient knowledge from the Arab world, which involved the use of a coating of stanniferous glaze on the terracotta that made the artifacts shiny and very durable.

The Della Robbia family, however, had the merit of spreading its use in monumental sculpture, experimenting with its possibilities and perfecting the technique to very high levels, handing down the secret of this workmanship only within the family. Thus it was that the Della Robbia's polychrome glazed ceramics, still known today as robbiane, in a short time not only conquered Florence, but spread from there to the whole of Tuscany, and then to the national borders and far beyond these.The Valtiberina was no exception, where, on the contrary, robbiane had an inordinate success, so much so that in practically every town in this splendid valley one can find significant evidence of them. The reason for the fortune and widespread diffusion in this area of the technique is probably to be found in multiple motivations, which are intertwined with the story of Andrea Della Robbia (Florence, 1435 - 1525), grandson of Luca, his disciple and heir to the family's knowledge.

To him we owe an iconographic turn in the production of glazed terracotta in a more devout and transcendent direction, and less austere than was characteristic of Luca's production. His works are cloaked in a chaste and humble language, more emotive and sentimental, certainly more inclined to popular sensibility and Franciscan spirituality and more generally that of the mendicant orders. And for that matter Andrea's religious inclinations are testified to by Vasari: "He left two sons friars in San Marco who were clothed by the Reverend Friar Girolamo Savonarola, of whom those of della Robbia were always very devout."

The new aesthetics promoted by his ceramics therefore met Franciscan orientations, which his commissions frequently resorted to. And his role in the building site of the Sanctuary of La Verna in Casentino, just a few kilometers from the Valtiberina, one of the most relevant places of Franciscanism, must have been of nodal importance for its diffusion in this area. Here he left a rich series of works, consisting of monumental glazed panels. To the aesthetic and even symbolic reasons (robbiane, being earthen artifacts, are certainly more in keeping with a doctrine extolling poverty than other precious materials) were obviously added purely practical reasons. In fact, according to Vasari, exposed to very rigid climatic conditions "no painting, nor even very few years would be preserved," while "this beautiful invention so vague and so useful and maximally for places where there are waters and where for dampness or other reasons paintings do not take place." Moreover, robbiane had the added advantage of being easily transportable, thanks to their certainly low weight and the fact that they were moved in pieces and then assembled on site, allowing for long journeys, even to the most peripheral places. Their having been successfully employed in such a revered and sacred place as La Verna and their merits of affordability, transportability and durability, as well as brightness, decreed the fortunes of the robbiane in this area.

One can trace a conspicuous number of works that critics have ascribed directly to the hand of Andrea or his workshop, some of which were used for devotional and liturgical purposes, while others were the result of secular commissions and purposes: as is the case, for example, with the numerous production of the noble coats of arms, which since the 1570s have come out with increasing continuity from the workshop of Andrea and his heirs, to encrust the facades of the Tuscan praetorian palaces, thus putting to maximum use that peculiarity of resisting atmospheric agents, and therefore probing an opportunity that had not been considered when the workshop was conducted by Luca. Thus, on both the Praetorian Palace of Anghiari and those of Sansepolcro and Pieve Santo Stefano, among the numerous coats of arms in pietra serena, one can also discern some in glazed terracotta.

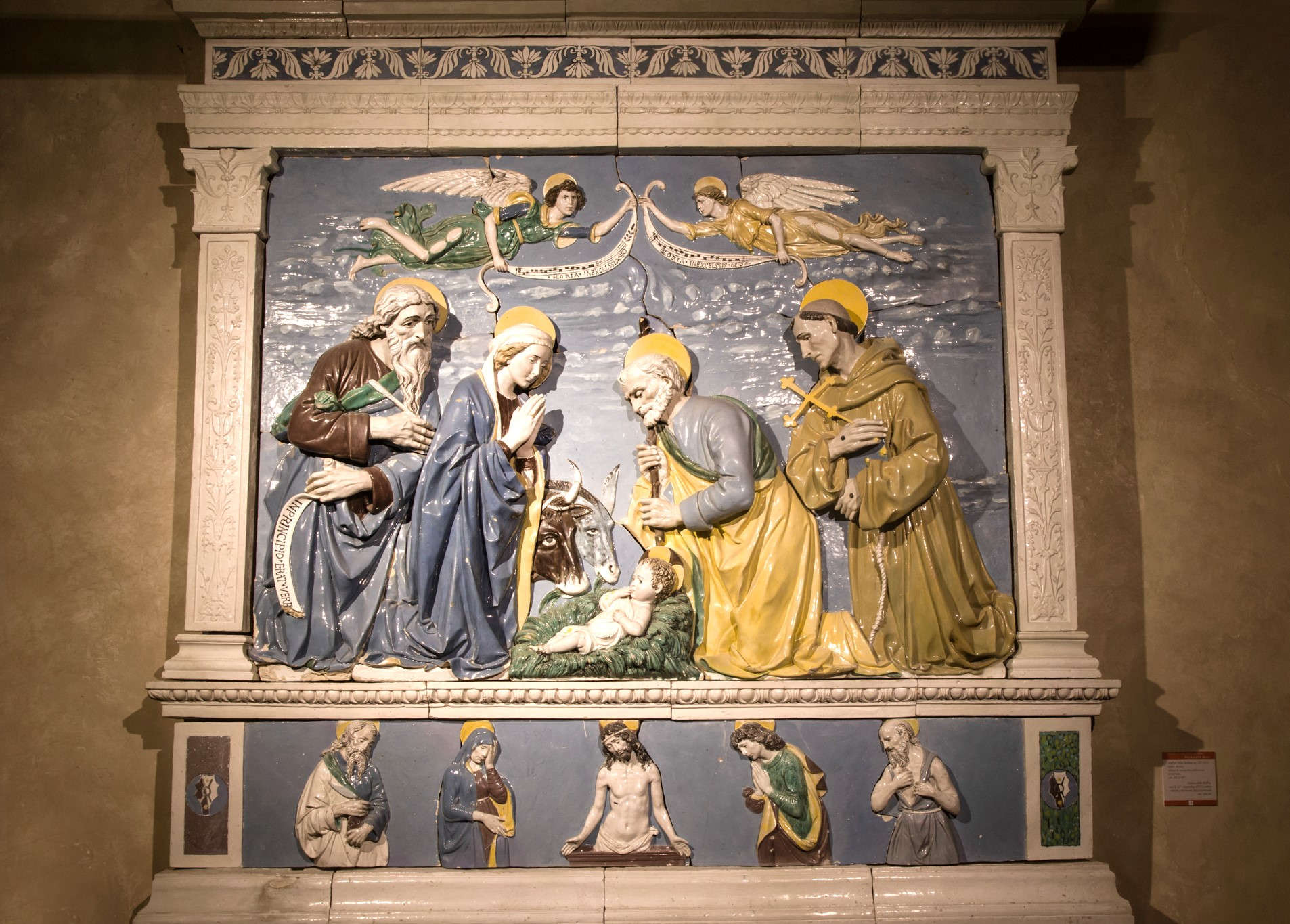

Also attributed to Andrea is the large terracotta altarpiece representing the Nativity and Adoration of the Shepherds, dated 1485 and now kept in the Museo Civico in Sansepolcro, but made for the monastery of Santa Chiara, and then moved to a chapel in the adjoining church, where it was seen by Marcel Reymond, who wrote about it in his 1897 publication Les Della Robbia, one of the first texts devoted to the family of Florentine ceramists. For the Frenchman, the work belonged to a late Andrea manner, when, with advancing age, the sculptor began to complicate his compositions, with more agitated rhythm and animating the work with a greater number of characters, in a more painterly stylistic rendering. The nativity that occupies the central compartment framed by a sober architectural frame with pillars in classical taste canonically represents the scene, while with lively naturalistic flair the vegetal setting is rendered. Completing the work at the top is a lunette with theAnnunciation and a predella at the bottom with four angels and at the ends genuflected St. Francis and St. Clare.

Also in the Museo Civico is another work by Andrea, one of his very widespread tondi with a Marian subject, probably executed for Bernardo di Filippo Manetti who was Podestà in Sansepolcro in 1502, as the family coat of arms held up by the angel at the top would allude to. Also in the city cathedral, there is a tabernacle of exquisite features by Andrea Della Robbia, and two relief sculptures the St. Benedict and St. Romuald (for others to be recognized instead as St. Blaise). The two Della Robbia figures of the founders of the Benedictine and Camaldolese Orders, respectively, are placed on the counter façade, and according to some scholars are to be addressed not to Andrea but rather to his sixth son, Luca della Robbia the Younger (Florence, 1475 - Paris, 1548).

Another significant work by Andrea, however, is found in Anghiari: it is the Madonna of Mercy, made for a monumental tabernacle in the town center, in what is now Via Garibaldi, where it has now been replaced by a copy. In contrast, the original commissioned by the Confraternity of Santa Maria della Misericordia del Borghetto has stood since 1938 on the high altar of the church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The Virgin while being crowned by angels, welcomes under her ample cloak a swarm of praying believers seeking protection, among whom ecclesiastical and lay bystanders can be distinguished, including a soldier in armor to be recognized perhaps as Iacopo Giusti or Gregorio d'Agnoluccio del Piccino, known as l'Anghiarese, two men-at-arms in the pay of the Florentine Republic who fell in battle and left their property to the confraternity.

The Museum of Palazzo Taglieschi also has some Della Robbia: a Nativity attributed to Andrea, less sophisticated than the one in Sansepolcro, but with more complex polychromy. Other ceramics follow, of which it is worth mentioning the lunette with Jesus and the Samaritan woman at the well, from the Bargello and attributed to the Buglioni workshop.

The Buglioni family from the eighth decade of the 15th century represented the alternative to the Via Guelfa workshop. The progenitor was Benedetto Buglioni (Florence, 1461 - 1521), a probable pupil of Verrocchio: according to Vasari, he got hold of the Della Robbia's secrets through an espionage carried out by a woman in the house of the famous ceramists. Despite the insinuation, it is likely that Benedetto came to know the technique by initially collaborating with Andrea. Buglioni's production, however, was characterized by an accentuated polychromy in a naturalistic direction and a simplification of Della Robbia models, a feature that entailed faster processes and lower prices, which certainly contributed to the fortunes of this workshop. They were joined by Santi Buglioni (Florence, 1494 - 1576), Benedetto's nephew, remembered by Vasari as the one "who alone knows how to work this sort of sculpture today." A fine terracotta altarpiece is preserved by Santi in the church of Sant'Agostino in Anghiari, depicting anAdoration, where the traditional Della Robbia color scheme is replaced by a bright polychromy and the compositional solution is inscribed in a blatantly Mannerist style.

The theme of Jesus and the Samaritan woman at the well also recurs in a splendid altarpiece, preserved in the Palazzo Pretorio in Pieve di Santo Stefano. Attributed to Girolamo della Robbia, it was originally displayed outside, commissioned by the Florentine vicar Giuliano di Guidetto Guidetti to adorn a public fountain. In the background of the sacred scene is a fresh account of the landscape of the time in the direction of La Verna. Also in the Collegiate Church of Santo Stefano are other marvelous Della Robbia works, including an altarpiece with Assumption of Mary among Saints from the workshop of Andrea della Robbia and a delicate all-round ceramic of an ephebic Saint Sebastian, ascribed to Giovanni della Robbia.

In Badia Tedalda is the church of San Michele Arcangelo, where even the entire decorative cycle is entrusted to the Robbiane, which were commissioned by the powerful bishop Leonardo Bonafede from the workshop of Benedetto and Santi Buglioni. The high altarpiece with the Madonna and Child between Saints Leonard, Michael, Archangel and Benedict, of refined neo-fifteenth-century taste, is the last documented work on which Benedetto worked. Upon his death, the workshop was carried on, as mentioned above by Santi, who in addition to other works in the church, also made TheIncredulity of St. Thomas, for the small church of Montebotolino.

From Pocaia, a hamlet of Monterchi where there is the church known as Madonna Bella, because it was built in the 16th century to house the image of the Virgin of Santi Buglioni, much venerated by the local community local community, to the parish church of Saints Ippolito and Cassiano in Caprese Michelangelo, the list of these marvelous inlaid treasures in the area is still long and certainly cannot be exhausted within the proper limits of an article, as evidence of an extraordinary heritage of translucent works, which deserves to be known.