The Farnese Palace in Caprarola, a masterpiece of Italian Mannerism

In the province of Viterbo is a monumental residence that has few equals in the world, as it encompasses wondrous architectural solutions and an immense pictorial cycle.

By Jacopo Suggi | 05/05/2025 19:44

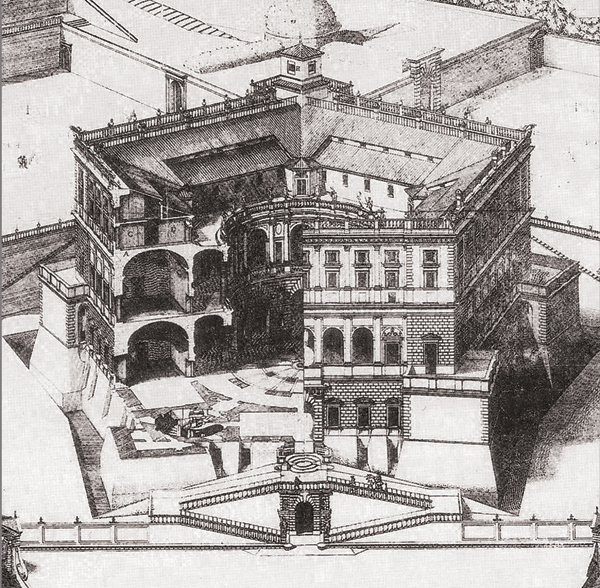

In Caprarola, a small village in Tuscia in the province of Viterbo, surrounded by the Cimini Mountains, is Palazzo Farnese, one of the most extraordinary residences built in Italy in the 16th century. It is undoubtedly one of the most brilliant jewels of late Mannerism, where some of the most important artists and architects collaborated, resulting in a building of gigantic dimensions, a happy combination of innovative architectural solutions and stunning pictorial decoration, both in quality and size. The monumental complex that dominates Caprarola from the top of the tufa spur on which the settlement is built still links its name to the family of patrons who built it, and who retained possession of it for a long time.

The Farnese were a dynasty that in a relatively short time was able to assertively impose itself on the European scene, so much so that it influenced world balances. In the palace of Caprarola one can read the culmination of the economic and social rise of the ancient family, which saw in Alessandro Farnese (Canino, 1468 - Rome, 1549) a nodal figure who marked the apex of the power of the lineage, first wearing the cardinal's purple and later ascending to the papal throne with the name of Paul III in 1534. It was Alessandro Farnese himself who decided to commission the celebrated Antonio da Sangallo to build a mighty fortress in a shepherd's village, which began around 1521. The efforts of Sangallo, famous for his military architecture and also mentioned by Vasari, led him to choose a fortress with a pentagonal plan, a solution also adopted for the almost contemporary Fortezza da Basso in Florence. Work on this monumental fortress, in which Baldassarre Peruzzi was also involved, lasted until 1534, and in the same year Paul III appointed his 14-year-old nephew, also named Alessandro, also known as Alessandro the Younger (Valentano, 1520 - Rome, 1589) or as the "Great Cardinal," for his political enterprise and the vast contribution he made to the arts, as cardinal.

It was the latter who resumed work on the Caprarola building site after a long period of interruption. Although the events and construction dates are not entirely clear, it is believed that around 1557 he turned to Jacopo Barozzi known as the Vignola to complete the building, although he did not take on the task until 1559. Times had changed, however, and the project no longer envisioned a mammoth fortress so much as a sumptuous residential palace.

Even today it is not so simple to decree with certainty which architectural gimmick is to be ascribed to Sangallo's or Vignola's design: clearly the pentagonal plan, the moat dug into the tuff and the angular ramparts are to be attributed to the former, while the staircase system and the rearrangement of the surrounding urban layout, creating a long straight artery that serves as a perspective axis and ceremonial route, and the square that scenographically surrounds the palace are by Vignola. Vignola also intervened massively on the pre-existing structure, softening it in appearance to accommodate the new use, opening up the curtain wall at the height of the piano nobile to make way for a luminous loggia and truncating the bastions to make terraces, and redesigned the inner courtyard.

By 1573, when the architect died, the palace must have been nearly completed, although some interventions, including the pictorial ones, lasted until Alexander's death in 1589. However, around 1580 the general layout must have already appeared almost complete, if such an illustrious visitor as the philosopher and politician Michel de Montaigne, during his trip, could report an enthusiastic impression of it: "From there following the straight road we stumbled upon at Caprarola Palazzo del Cardinal Farnese: which is of the greatest cry in Italy. I have not seen any in Italy that stands breast to breast with them." And indeed the Farnese Palace in Caprarola has few equals in the world: a gigantic building where every intervention, whether architectural or pictorial, is designed to exalt the dynasty and its patron. This makes any attempt to recount such magnificence a very difficult undertaking, here where more mind-boggling than the architecture itself is the decorative program that unfolds inside, in a horror vacui of paintings that run on the walls and vaults of most of the rooms.

As soon as one enters the structure, one encounters an airy vestibule, known as the Hall of the Guards, since it was intended for guard duty at the villa. The paintings in this first room, created by Federico Zuccari and aides, serve as a kind of introduction to the master of the house; indeed, the coats of arms of the Farnese family stand out on the vault, along with views of the palace itself and of the village of Caprarola undergoing renovation, magnifying the contribution of Alexander, the true architect of these operations. Thus the two views with naval scenes on the walls underscore the role of the Grand Cardinal as defender of Christendom, involved in the commission commissioned by Pius IV to deal with the Turkish threat. The spaces on this floor known as the floor of the Prelates and intended for distinguished guests are organized around the courtyard, the centerpiece of the palace. The courtyard is in the shape of a circle perfectly inscribed within a pentagon, in an architectural solution rare in Renaissance dwellings, but so desired by the commissioner because of its symbolic implications, perhaps recalling the palace of Emperor Charles V in Granada and the Villa Madama in Rome, built at the behest of Pope Leo X.

In Sangallo's early design, too, the courtyard took the same form, but it is likely that Vignola's efforts focused mainly on softening the space and ensuring maximum symmetry. This, in fact, is circumscribed and punctuated by a double order, the lower portico composed of arches and pillars decorated with an ashlar motif in peperino, a rock of volcanic origin widely used in Tuscia constructions, while above it develops a portico composed of Ionic half-columns. In order to preserve symmetry, the measure of the courtyard's diameter, about 21 meters, corresponds to its height, and for this reason the two floors intended for the family are set back, thus being hidden from view. The portico that crowns the courtyard has a dense pictorial decoration made between 1579 and 1581 under the direction of Antonio Tempesta, and depicts on the vault mock trellises with ever-changing textures, filled with fruit and flowers and animated by birds of different species, while on the walls tower more than forty coats of arms of the families related to the Farnese.

The portico leads to the guest apartments, divided into summer and winter, which are also embellished with sumptuous, fully decorated halls. Perhaps the most sumptuous is the Sala di Giove: here guests, amidst perspective openings and a rich weaving of grotesques, could admire the scenes painted by Taddeo Zuccari that tell the story of the god while still a child, rescued by his mother Rhea from the jaws of his ferocious father Saturn, and then given to the nymphs who weaned him to Crete on Mount Ida, where he was suckled by the goat Amalthea, who finally obtained as a reward his assumption into heaven to become a constellation. The cycle draws legitimacy from a commentary by Servius on Virgil's Book VII, according to which the nymph Melissa and Amalthea settled on Mount Cimino, and therefore the goat would become an allusion to Caprarola, while Jupiter would be identified with Cardinal Farnese.

Another marvel of the palace is the sumptuous royal staircase that runs from the basement floor, where it welcomed guests arriving by carriage, to connect the floor of the Prelates and the piano nobile. The helicoidal staircase designed by Vignola and widely celebrated by his contemporaries was a model for numerous other staircases, including the one built by Borromini for Palazzo Barberini. The architect of the Farnese family was in turn inspired by Bramante's great "snail" in the Vatican, but he gave it a more monumental scope by outfitting it with mighty Doric columns and peperino pilasters. These in their gray coloring contrast against the persuasive colors of the paintings that open the room to the outside world evoking fantastic landscapes and grotesques extolling the exploits of the Farnese family. In the dome that dominates the staircase, the center is occupied by the blazon of the Farnese family with the six blue lilies on a gold background, crowned by two putti wearing Cardinal's headgear, while around it in a radial pattern spreads a grotesque motif of various female allegories protruding from niches. Traditionally attributed to Antonio Tempesta are the landscape scenes, while still anonymous remains the author of the dome. And if on the floor of the Prelates the decorative program that magnifies the Farnese dynasty is hermetic, on the piano nobile it becomes uncovered and intelligible.

In the Loggia di Ercole, now a space enclosed by stained-glass windows overlooking the town of Caprarola, a cycle unfolds on the vault and in the lunettes where the sinewy mythical hero becomes the personification of Alessandro Farnese. Once again, myth is used to exalt the Genius loci. According to Servio's commentary, Hercules, being in the Cimini Mountains, was involved in a test of strength during which he thrust a spear into the ground; no one was able to remove it until the demigod himself drew it out, causing an abundant spring of water to gush forth, which gave rise to the nearby Lake Vico. The cardinal must have felt this endeavor particularly akin to himself, having promoted reclamation works and interventions to regulate the lake's waters. Moreover, in the scene where the inhabitants in gratitude build a temple for Hercules, Vignola is depicted in the figure of the architect. The scenes were begun by Federico Zuccari, but completed by Jacopo Zanguidi known as Bertoja, who adapted his style to the work. Zuccari was in fact removed by the cardinal, with whom disagreements had arisen, essentially for economic reasons and his discontinuous presence on the site. The cycle is then completed by ten views that effigy the main Farnese territories such as Castro, Ronciglione, Parma and Piacenza, integrating with the panorama that opens from the loggia. As the views suggest, the original environment played on the ambiguity of a semi-open space, through also the enameled floor and the monumental fountain.

In the center of the marble basin stand three cherubs, two of whom ride a dolphin and a unicorn; above them rises a limestone grotto, topped in turn by a landscape of antiquated taste. The fountain, as well as the recurrence of water in the painted scenes, probably also assumed a religious significance, aimed at moralizing pagan representations. In particular, it may allude to baptism, a sacrament rejected by Lutheran heretics and at the center of the theological debate at the Council of Trent, convened by Pope Farnese.

Also striking is the adjoining chapel, created by Taddeo and Federico Zuccari, where episodes from the Old Testament are historiated on the dome, while on the walls the apostles, including Judas Thaddeus bear the likeness of Taddeo Zuccari, and James the Elder those of Vignola. On the altar dominates a Pietà, a wall painting that replicates the famous panel made by Taddeo, but which his brother Federico wanted to keep for himself.

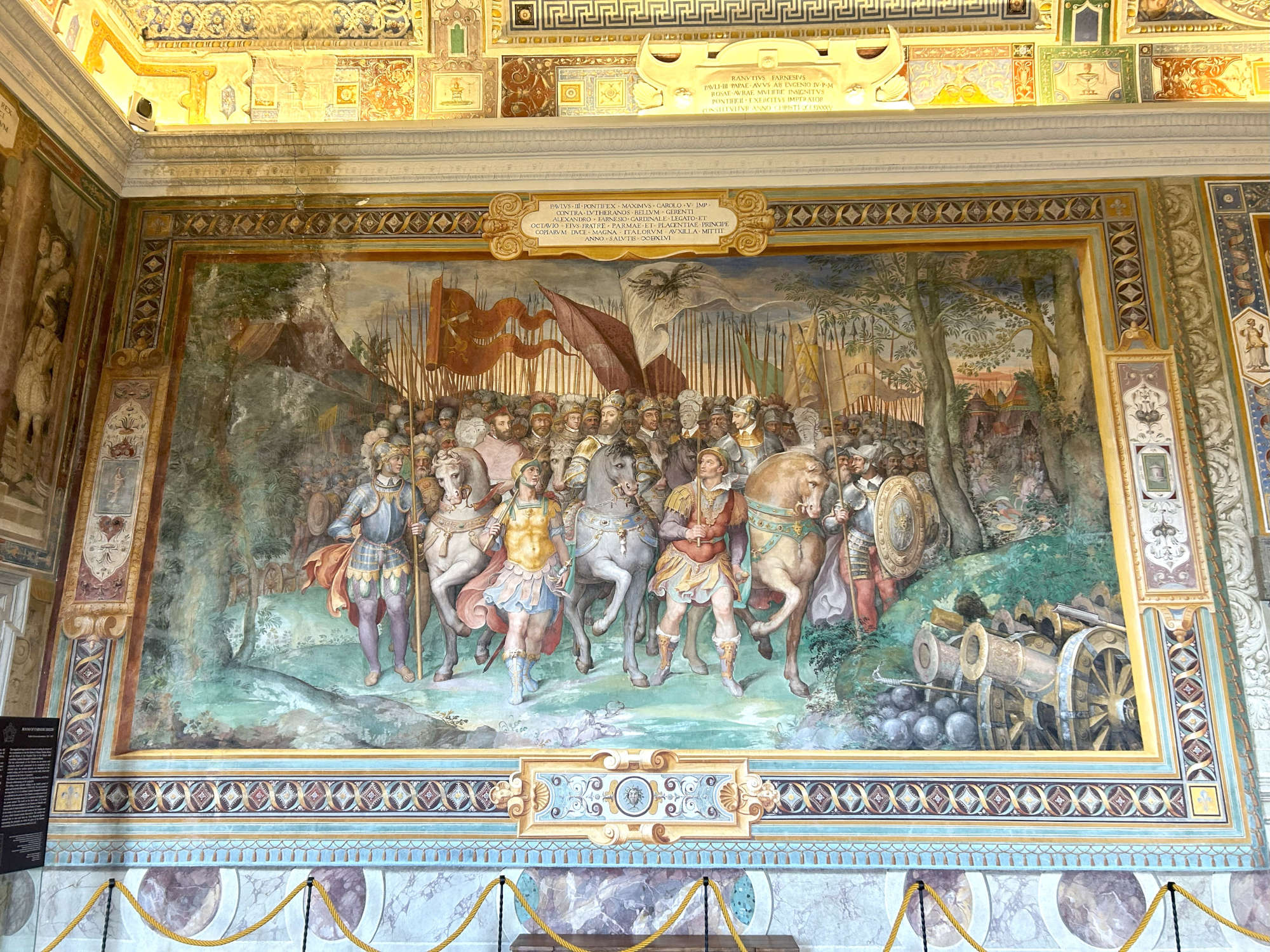

If in the chapel the propaganda program in favor of the House of Farnese is interrupted, it resumes even more strongly in the Hall of the Farnese Fasti. In the vast room with great clarity some of the highest episodes of the House of Farnese are restored, coinciding with the period of Paul III's pontificate, who unceremoniously distributed roles of great importance to family members. The pinnacle of the family's power was also reached with a far-sighted marriage policy, in particular the two marriages on the short sides of the room saw the pope's nephews tie themselves to the two superpowers of the period, France led by Henry II and Spain led by Charles V. These states were at war with each other, and the Farnese claimed their role as mediators, able to maintain the balance of the world. On the short sides, within ovals, are portraits of the rulers of France and Spain, who thus become symbolic protectors of the Farnese family.

On the long sides, on the other hand, it is Cardinal Alessandro who is magnified, involved in some military and diplomatic actions, or in favor of the family's possessions. The scenes are narrated with extreme clarity and meticulous attention to costumes and distinguishing marks. The physiognomies and clothes of the characters always recur the same, allowing the protagonists to be immediately identified, an objective also reinforced by the use of captions inserted in painted cartouches.

Even in theAnticamera del Concilio the narrative does not lose tenacity in its exaltatory objective of the Farnese family, and in particular of the real progenitor, Paul III, to whom all the painted scenes are dedicated. The name of the room takes its cue from the scene illustrated with the opening of the Council of Trent (1545-63), which was convened by the Farnese in response to the spread of Protestant doctrines. The other episodes historiated on the walls and walls further vindicate the great activity of the resolute pontiff, whose foresight is highlighted in the scene in which he appoints cardinals, four of whom became his successors to the papal throne, Julius III, Marcellus, Paul IV, and Pius IV. In this way Alexander also attributed to the Farnese the role they played as arbiters of the world.

In the many private rooms of the apartments, the decoration becomes more intimate and leaves the exalted register behind, to propose figurations that accompany the function of the rooms, such as the Chamber of Dawn, once a bedroom accompanied by allegories, personifications and myths related to the night and sleep, while in the room used for dressing all the scenes concern the theme of clothing and textiles, or in the Room of Solitude, the cardinal's study, a eulogy to thinkers, philosophers and politicians takes place. Among the most interesting pieces should be mentioned the depiction ofErmatena, painted by Federico Zuccari. This is an androgynous figure resulting from the fusion of Mercury and Minerva, an allegory of eloquence and wisdom, and a probable reference to the role of patron that Alexander boasted over the Bolognese Accademia Bocchiana, which had elected these two deities as its symbols. In two other sumptuous rooms, the Anticamera degli Angeli and the Sala del Mappamondo, the pictorial tone returns to declamatory and public. In the former, the success in the doctrinal and spiritual work of the Tridentine Council is reinforced; the scenes illustrated on the walls show the role of angels as divine instruments, bearers of mercy and rewards for the righteous and capable instead of tremendous ruthlessness toward those who have betrayed the Lord's will. On the vault unfolds the bloody battle of the Expulsion of the Rebel Angels, where naked bodies intertwine, between the angelic hosts and malevolent demons that almost seem to overflow the frame, risking falling into the visitor's space. The cycle was begun by Bertoja, and upon his death completed by Giovanni de' Vecchi and Raffaellino da Reggio.

In contrast, the Sala del Mappamondo becomes a perfect compendium of the role of supreme observer and judge of the world's destinies that the Grand Cardinal claimed for himself. The fate of the globe is observed through the maps painted by Vanosino, illustrating the four then known continents, the planisphere and Judea and Italy, that is, the lands of origin of Christianity and the Church. The celestial ones, on the other hand, are manifested in the vault, where constellations are flanked by zodiac signs. Towering above the maps, within ovals, are portraits of great explorers who wrested lands from the unknown through their discoveries, such as Magellan, Columbus, Cortés and Marco Polo. This reception hall also witnessed a banquet in honor of Pope Gregory XIII, who after visiting it wanted to commission the gallery of maps in the Vatican.

The complex also has two secret gardens, insulated from the outside with high walls and embellished with scenic nymphaea, and a perspective system engraved on a portion of the hill, organized as a walk through the greenery to reach the Casina del Piacere, which was created for hunting but also became a refuge for Cardinal Farnese. This is an exquisite little villa that scenically dominates the landscape with a vast system of terraces, fountains and caryatids.

In the Palazzo Farnese in Caprarola one can still read the yearnings and hegemonic appetites of a family that in a short period of time was able to forcefully impose itself on the world political scene.