London's Royal Academy of Arts, the masterpieces of a little-known museum in the English capital

With its centuries-long history, the London institution has accompanied the most important moments in British art. It still maintains its appeal today through important collections open free to the public.

By Jacopo Suggi | 13/05/2025 16:06

Each of us has a firm conviction not to be part of the masses, to break away from the qualunquialisms and common customs that a massified society has imposed: it is also with these intentions that we set out on vacation, certain that we will carve out nonconformist itineraries not abused by tourism. Only then do we end up betraying every intention, children of a mainstream culture that we have absorbed through TV, cinema and social media. Finding ourselves in London, we cannot avoid visiting places that have become famous over time for various reasons but that, in a globalized world, have lost some of their charm, repurposing atmospheres, stores and attractions that we find not dissimilar in many other cities: this is the case, for example, of Carnaby Street or Camden Town. Another case in point is Piccadilly Circus, the famous square that sits on a major London thoroughfare and, in addition to a certain vibrancy, is known for its neon and lcd billboards. These illuminated signs have been present, obviously involving other technologies, since the very first decades of the 20th century, and for a long time they were to be experienced as signs of great modernity, a distinctive symbol of the London metropolis, but today they are but the norm in any large or medium-sized city. However, just a few hundred meters from the world-famous crossroads taken by storm by hordes of tourists, there is a place that retains its charm unchanged, the result of a prestige that summed up centuries, capable of standing as a "middle ground between tradition and innovation," in the words of Winston Churchill himself. This place is London's Royal Academy of Arts, based in the splendid Burlington House, and it is a destination that the art enthusiast should not miss on his or her visit to the English capital.

The Royal Academy of Arts is one of the most famous and prestigious art institutions and academies in the world, a place that plays a key role in the geography of European art. Its origins date back to the 18th century, a time when the lack of a major organization for training artists became increasingly pressing. Until that time, in fact, a few small private academies had operated, nothing comparable to the large and ancient institutions already present for centuries in Italy and other nations of Europe. After a few unsuccessful attempts, in 1768 the architect Sir William Chambers presented King George III with a petition, signed by thirty-six artists, advocating the need to open a society to promote the arts, capable of acting as a school, but also capable of organizing exhibitions and directing public taste. The king accepted the proposal, founding the academy with a personal act and guaranteeing financial support. The great English painter Joshua Reynolds was appointed its first president, while prominent figures such as Thomas Gainsborough, Angelica Kauffman, William Chambers, Benjamin West and many others appeared among the founding members. Thus began the history of the Royal Academy of Arts, flanked by the Royal Academy Schools and famous for its famous exhibitions, now known as Summer Exhibitions.

The problem of a venue, however, was still far from having a resolution: initially the new institution rented some cramped space in Pall Mall, from 1780 instead it found hospitality in the sumptuous public building, the new Somerset House, built by Chambers, at that time treasurer of the Royal Academy, to house some government offices.

But the pilgrimage had not come to an end, and in 1837 it found temporary tenancy in the rooms of the National Gallery's new, and current, home in Trafalgar Square, a building also constructed by an academic, William Wilkins. Finally, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of its founding, the British institution moved to Burlington House in Piccadilly, once the private residence of the Earls of Burlington but later to become state property, and here it still stands today in the main building that makes up the complex, for the remainder occupied by other academies, including the Geological Society of London, the Linnean Society, the Royal Astronomical Society, the Society of Antiquaries and the Royal Society of Chemistry.

In its centuries-long history it has seen among its academicians some of the greatest names in British art and beyond, practically impossible to name them all, but the following list suffices as an example: Heinrich Füssli, Thomas Lawrence, John Soane, J. M. W. Turner, John Constable, John Everett Millais, Eduardo Paolozzi, David Hockney, Joe Tilson, Jenny Saville, Tracey Emin, Gilbert & George, Anish Kapoor. In addition, it has been a promoter of and involved in numerous artistic endeavors destined to mark art history, among which exhibitions have been of no small importance.

The annual exhibitions or Summer Exhibitions are perhaps the RA's most identifiable initiative, and have been organized since 1769-they are considered the longest continuously staged art exhibitions in the world. Anyone can attempt to participate, except to be selected, and more than 1,000 artists, both emerging and established, exhibit there each year. Today it is open to any medium, but it has not lost its typical encrusted layout, presenting works side by side in a kind of horror vacui. But there have been many other Royal Academy exhibitions that have set the standard, such as those devoted to the Old Masters, which had the merit of spreading the taste for the Primitives, or the Italian Art Exhibition of 1930, which brought to London, not without risk, incredible Italian masterpieces such as Botticelli's Birth of Venus or Donatello's David and which was strongly advocated by Mussolini for propaganda purposes.

In times closer to home, the 1997 Sensation exhibition was extremely significant and also fueled much controversy, which, set up thanks to works from Charles Saatchi's collection, introduced Young British Artists, such as Damien Hirst with his famous shark, Tracey Emin's tent, and Marc Quinn's self-portrait made with his own blood. Today, exhibition opportunities have greatly increased, and the Royal Academy provides a rich program of exhibitions, devoted to famous names and others less well known. Still that peculiarity that Churchill pointed out, of standing between tradition and innovation, is perhaps one of the Royal Academy's most preponderant features and one of the reasons why, though less mentioned on tourist routes, a visit to Burlington House will not leave one disappointed.

The sumptuous building, whose origins can be traced back to the 17th century, has been remodeled several times, changing from Baroque to neo-Palladian architecture, punctuated by columns and pilasters, and niches housing statues of scholars and artists, while a statue by Reynolds towers in the courtyard. The interiors are also sumptuous and embellished with paintings by Kauffman, West but also Sebastiano Ricci.

Instead, the old, austere rooms are now lively and engaging, thanks in particular to a major renovation carried out on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of its founding and orchestrated by renowned architect David Chipperfield, also an academic. Inside are a shop, cafes and restaurants, a tiered auditorium, and, of course, exhibition spaces.

Admission to Burlington House is free, as is viewing some of the displays scattered along the structure, where works by members that are also for sale or by young students attending the Academy are cyclically displayed; in contrast, temporary exhibitions are priced not inconsiderable.

Fortunately, a visit to the Royal Academy's collection also remains free. It is a collection that has tens and tens of thousands of works: donations from members, cast plaster casts used in the past for study, and other ancient works, bequests or purchases always aimed at the education of students. The collection has a particular physiognomy, as the works were not selected by collectors or curators, but by the artists themselves, who often choose them because they are representative of their practice or show some states of execution such as sketches and sketches.

This boundless collection is displayed on a rotating basis in a number of small, long-lasting but temporary exhibitions, although some highlights enjoy better luck than others. The works are collected in small thematic exhibitions, ranging from architecture to design, but perhaps the most significant are found in the Collection Gallery, a space contained in square footage but highly curated. Organized into small focuses, the exhibition brings together past and contemporary works.

The center of the small gallery is occupied by works that refer to three of the most important protagonists of art of all time, masters on whom academics trained for centuries, namely Raphael, Leonardo and Michelangelo. Two monumental copies of famous works by the first two face each other in a magniloquent dialogue. Significant is the reproduction from Leonardo's Last Supper painted for the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. For a long time scholars questioned the authorship of the copy, naming Giampietrino, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio and Marco d'Oggiono, artists who were students in Milan of the Tuscan artist. In more recent times it has also been speculated that Giampietrino began the painting, which would later be finished by Boltraffio. The work, dated around 1515-1520, has almost the same dimensions as the original, although it deviates from it because it lacks the entire representation of the upper part, probably cut off to fit some location: in fact, in the original Leonardo painted the vault of the room, turning it into a perspective box. However, it shows some details no longer visible in Leonardo's masterpiece today, such as the salt shaker overturned by Judas's right arm and Christ's feet that were lost with the opening of a new door in the convent's refectory.

The great copy remained for some time in the hands of a private individual, until at the end of the 16th century it was purchased by the Charterhouse of Pavia, where it remained until 1793, when following the suppression of religious orders it was first displayed at the Brera Academy and then in 1817 taken to London to be sold. Finally, the painting, as Füssli recalled, was "rescued from an accidental pilgrimage by the courage and vigilance of our President who was then Sir Thomas Lawrence."

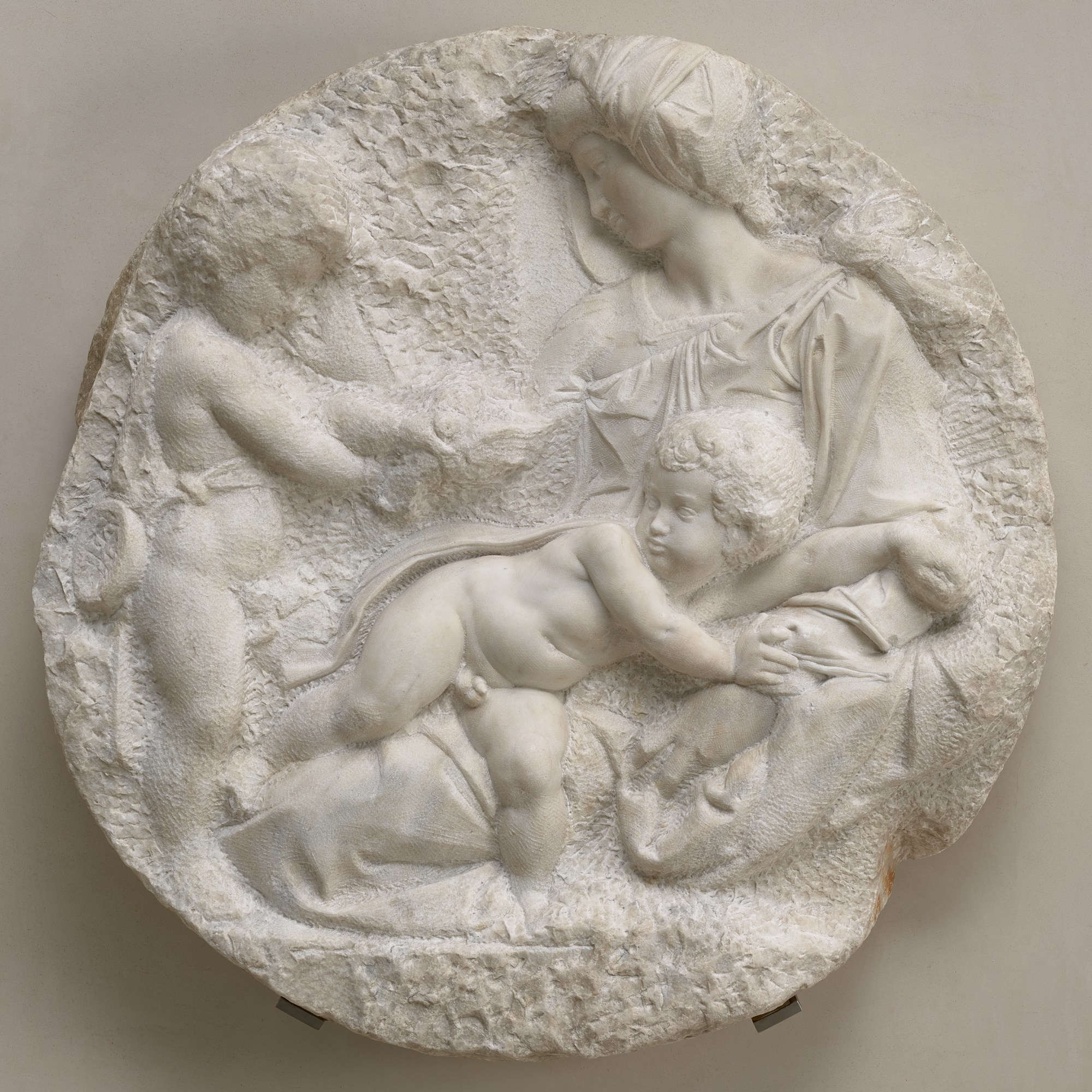

Fronting theLast Supper is a triptych of works by James Thornhill, copies from cartoons that Raphael made at the request of Pope Leo X to be translated into ten tapestries for the Sistine Chapel, now in the Vatican museums. King Charles I wanted to purchase seven of the ten original cartoons, which soon became emblematic models of the classical style on which generations of painters were trained. But the real masterpiece of the collection is the Tondo Taddei, a marble bas-relief made between 1504 and 1506 by Michelangelo, depicting the Madonna and Child with St. John. The work, made for the private devotion of wealthy merchant Taddeo Taddei, was never completed, adding to the long list of Michelangelo's "unfinished" works. There has long been debate over the correct reading of this work, where the Baptist, denoted by the attribute of the baptismal bowl, presents Jesus with a goldfinch, a symbol of the Passion. For some scholars, the Messiah is portrayed in the act of retreating fearfully to find comfort in his mother's arms, while others have proposed that it is simply a playful pose. What is certain is the great dynamism of the composition. Then the hypothesis of the influence of Leonardo's sfumato, discernible in the unpolished contours, has come forward, suggested by the unfinished conduct of the work. The bas-relief, the artist's only work in a British collection, was immediately hailed by the British, with Constable calling it "one of the finest works of art in existence."

Numerous other works highlight their didactic value, such as casts of the Laocoon and Belvedere Torso, a "disfigured and shattered fragment" that nevertheless, according to Reynolds, showed the "traces of superlative genius." Thus, sketches and studies by Thomas Lawrence show the studies he made of Raphael and Michelangelo, particularly for the characterization of the rebel angel in the work Satan summons his legions, shown at the Royal Academy's annual exhibition. And still numerous other sketches, drawings, palettes and pigments show procedural stages of the artistic craft of Reynolds, Constable, Millais and many others.

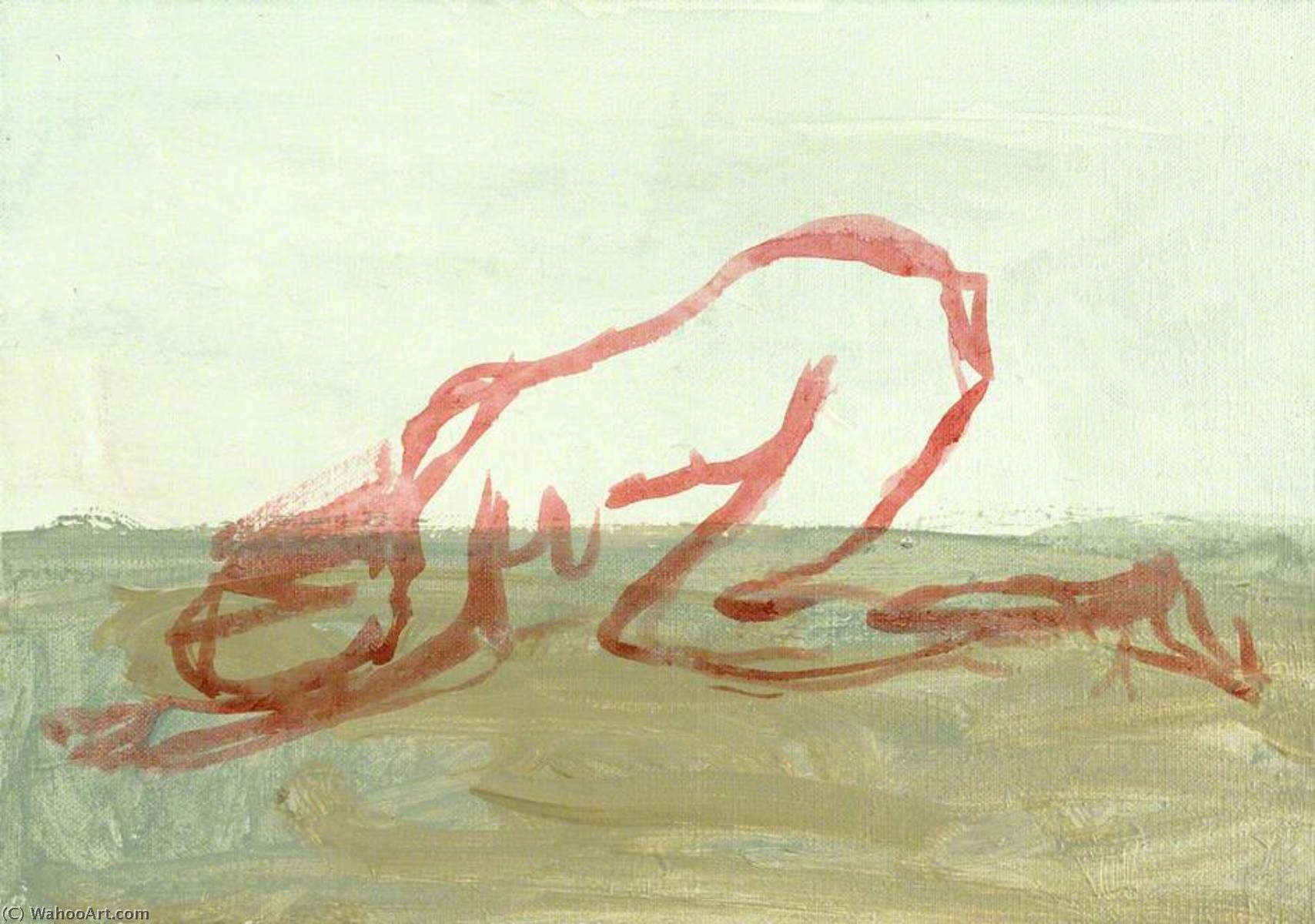

Currently, the collection also exhibits works by contemporaries, such as Trying to Find You 1, a small painting by Tracey Emin, a British artist who also taught drawing at the Royal Academy for a number of years. Here, a silhouette traced in red shows the evanescent figure of a woman in a prone position, in an ambiguous mixture of a prayer, a sign of submission and a reference to sex.

Still numerous are the works on display, alternating between big names and others perhaps less famous, but once again denoting that position of the Royal Academy of Arts poised between an established tradition and openings to the new. For this reason, Burlington House is a must-see attraction on any art enthusiast's London travel itinerary.