Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi in Rome: din of colored marbles and images of death

The church of Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi is one of the most extraordinary and surprising national churches in Rome: it is a riot of polychrome marble, but not only that. It is filled with funerary monuments that allow us to understand how, in the turn from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, the way death was conceived changed. A new installment of Federico Giannini's "The Ways of Silence" column.

By Federico Giannini | 08/06/2025 15:56

There is a work by Canova among the colored marbles of the church of Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi in Rome. It is certainly not counted among his masterpieces, much less listed among his best-known works, and most do not even know of its existence. The funerary stele of Alexandre de Sousa Holstein is the result of a production that we might say almost serial, it is one of the many bodies that punctuate a very wide constellation of monuments that Antonio Canova varied with few details: in the basilica of the Holy Apostles, a short distance from Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi, another stele can be seen, that of his friend Giovanni Volpato, who is considered the model for that of Sousa Holstein. The Portuguese diplomat's son, Pedro de Sousa Holstein, had seen it shortly after his father's death and asked Canova to execute a similar one for his parent. Again with the same scheme: the seated pietas , draped in a long peplos, is seated on a stool mourning the deceased before his portrait, a bust resting on a tall column.

Perhaps it is also to the credit of Canova and his funerary works that in the early nineteenth century a completely different image of death had spread throughout Europe than the one that enveloped seventeenth-century Rome. In Canova's mind, the funerary monument is a work faithful to its classical and etymological meaning as a testimony that perpetuates the memory of those who are no longer there, and meditation on death becomes secular, affectionate, private remembrance; it becomes a moment of recollection in which a feeling of disappearance prevails, understood as, Francesco Leone has written, "a sense of the correspondence of loving senses that binds the remaining family members to their departed loved ones, giving relief and meaning to grief." Canova, in all likelihood, had reasoned about Foscolo's Sepolcri , curiously published while the Venetian was in the process of finishing the stele for the diplomat, completed in 1808 and installed in the church of Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi much later, on November 16, 1816. Canova had perhaps been able to meditate at length on the poetry that defeats death, on the harmony that "conquers silence by a thousand centuries." A reflection aimed not so much at what will be next, but rather at what has been, and what continues to be for those who are alive. It is something completely different from what can be seen a few steps further on, in the chapel of St. John the Baptist, next to the great altarpiece with the Baptism of Christ by Giacinto Calandrucci, where the wealthy perfumer Giovanni Battista Cimini, who had built his fortunes on supplies of'essences to the papal court and who had obtained jus patronage of the chapel, had wanted to have his portrait and that of his wife Caterina Raimondi, attributed to a sculptor from Carrara, Andrea Fucigna, placed there. The plaque that commemorates the passing of Cimini, who died in 1682, is a blanket of black marble, a funereal veil bearing the mournful effigy of a skull resting on two crossed bones, with the eye sockets facing our eyes, as if to remind us that that fate is inescapable. We will become like him.

There is no jarring, however, with the feast of marbles surrounding Cimini's tombstone and that of his wife, placed exactly opposite. In the seventeenth century, death was experienced and celebrated first and foremost as a vibrant moment of passage to eternal life; it was considered the moment "of the assumption into heaven of the miles christianus," wrote Marcello Fagiolo. And the assumption was to be celebrated in a solemn way, there was almost rejoicing, one thought of the light that would welcome the deceased. There is then no inconsistency between those black headstones and the church's triumphal parade of marbles. On the contrary, Alexandre de Sousa Holstein's stele opens to the eyes of the faithful entering St. Anthony of the Portuguese almost as a disturbing element. A candid glimmer in the midst of a riot of colored spots. A gleam of purity, of whiteness, of stillness that interrupts the imaginative frenzy of an architect who had made the national church of the Lusitanian community in Rome a revelry of polychrome marble.

A nineteenth-century guide to Rome and its environs, published in 1861, dwelt on Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi without too much ado, but did not fail to praise its interior as one "of the most vague and rich, because of the quantity of colored marbles that give it a pleasant and svelte appearance," and of extolling "the gold and stuccoes" that "are lavished there unsparingly." The church stands on a widening where in ancient times there was a convent that housed Portuguese pilgrims passing through Rome. We are among the veins of medieval Rome trying to modernize itself, we are behind Palazzo Altemps, behind the via dei Coronari, behind Piazza Navona, not far from the via del Governo Vecchio, the "via Papalis" where in ancient times the processions of the pontiffs who s'settled on the throne of Peter, and where therefore stood the palaces of the Roman nobility of the Renaissance, in the midst of that vast network of buildings of worship that all the national communities of Rome dedicated to their saints. From here, in a five-minute walk, one can reach San Luigi dei Francesi, Santa Maria in Monserrato, San Girolamo degli Schiavoni, and virtually all the major national churches in the city. That of the Portuguese is one of the richest, despite its small size. It had been founded in 1440, with the permission of Pope Paul II, by Cardinal Antão Martins de Chaves, Bishop of Porto, and then, in the seventeenth century, the Portuguese community had decided that that building was too small and too un-sumptuous to convey in Rome a worthy image of the kingdom of Portugal: the ambassador had therefore mandated Martino Longhi the Younger to redo it practically from scratch, at the expense of the Portuguese crown.

It would be difficult to understand the glitter of the marbles of Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi without thinking of that international Rome that hosted dense communities of foreign immigrants devoted to the most varied activities, of that Rome "Grand Theater of the World" capable of attracting people from all parts of the planet who went to settle near the embassies, palaces, and centers where the diplomats, agents, cardinals, and dignitaries of their countries exercised their power. And national churches were perhaps the most effective weapon that foreign powers could deploy in that "symbolic warfare," as Claudio Strinati has called it, "made of pyrotechnics, images and festive machines" in which all the national communities of sixteenth-seventeenth-century Rome were engaged. Churches, then, were not just reflections of God's glory, not just buildings of worship that were meant to inspire wonder among the faithful: they were, perhaps above all else, witnesses to the wealth, prestige, and devotion of their communities. Martino Longhi the Younger, therefore, was given the task of designing a church that would be more beautiful than San Luigi dei Francesi, more than San Giacomo degli Spagnoli, more than all the other national churches. The work lasted fourteen years, from 1624 to 1638, but other building sites would drag on even after Longhi's passing, so much so that the dome would be finished decades later by Carlo Rainaldi, and the apse found a completed form under the direction of Cristoforo Schor almost at the end of the century.

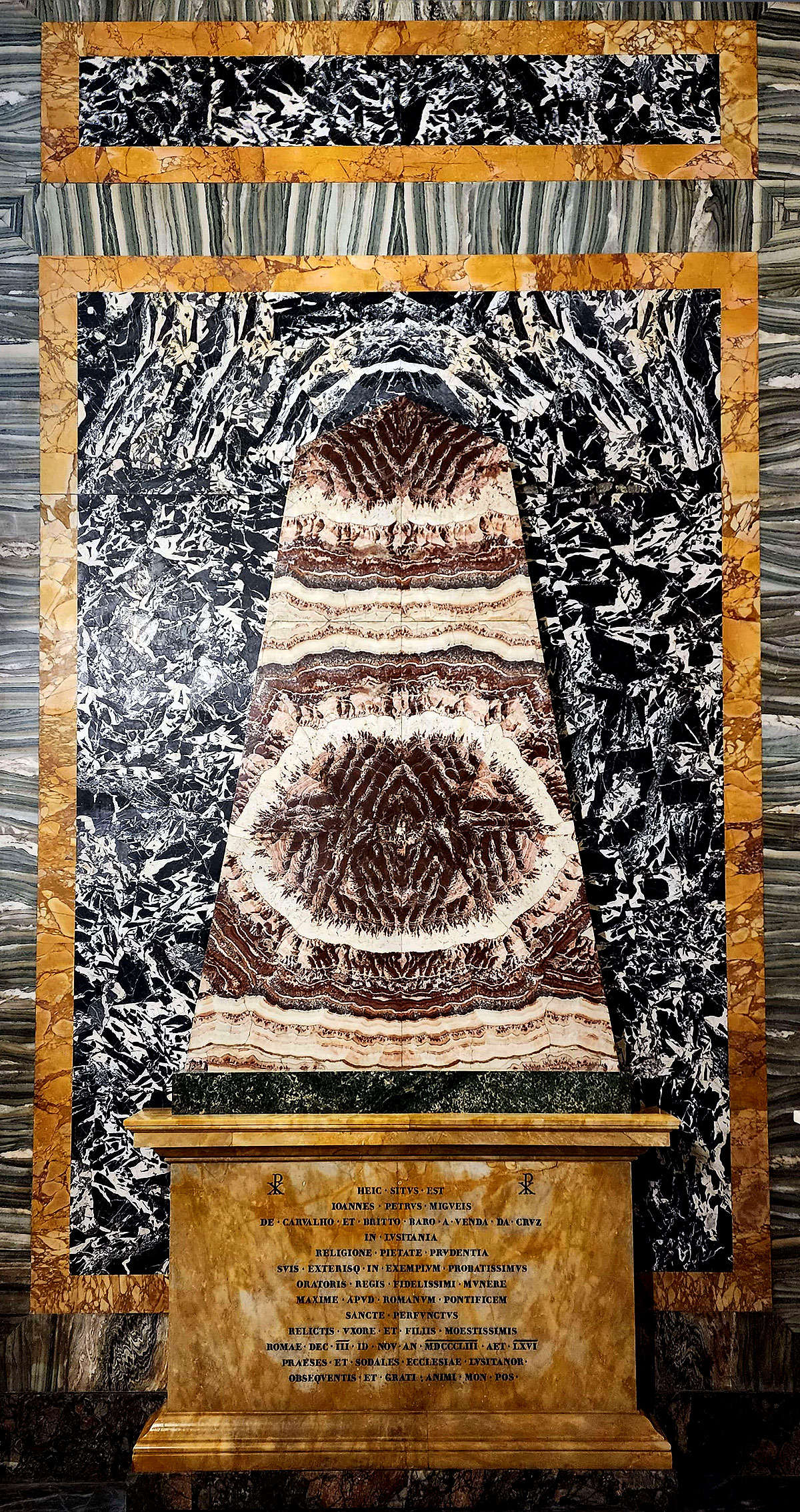

Today, those who enter St. Anthony of the Portuguese are almost overwhelmed by that overflowing symphony of marbles of every color. In the chapel of the Nativity, alternating bands of serpentine and French red frame the three 18th-century canvases by Antonio Concioli, with the Nativity surmounted by a broken tympanum in Siena yellow, invaded by a cascade of angels and cherubs pouring over the entablature. In the chapel of St. Catherine, Canova's stele stands out against a striking background in antique black, and looking across from it is the funerary stele of Ambassador João Pedro Migueis de Carvalho, dated 1853, in oriental alabaster worked in mirrored work and set on a base of antique yellow. The marbles in the chapel of St. Anthony Abbot enhance the gold background of the altarpiece, which is perhaps the church's most valuable painting, the Madonna and Child with Saints Francis of Assisi and Anthony of Padua by Antoniazzo Romano, Rome's greatest Renaissance artist, which, moreover, is quite rare to see in the city's churches: just the chance to admire this work (which was not originally here: it comes from another Portuguese-owned church, Santa Maria della Neve in Palazzolo, in the Alban Hills) would be worth a visit to the church by itself. Surrounding Antoniazzo's painting, beyond the two columns in veined black, is an uproar of alabasters, of yellow from Siena raging all over the walls, of red from France separating the elements, with splashes of white Carrara statuary at the bases of the columns, in the capitals, in the balustrade.

And then the high altar, where the altarpiece, the Virgin holding the Child to St. Anthony, by Giacinto Calandrucci in 1692, is raised in triumph by the glowing marble decoration designed by architect Francesco Navone and put in place by stonemason Francesco Ferrari, who finished the work in 1774, in time for the jubilee the following year. Here, large pilasters in jasper from Sicily, worked in quadruple mirrored stain, lead the eye to the panels of bardiglio, antique yellow and peach blossom that escort on either side thehigh altar, with its columns of French red, the plinths with alabaster paintings, the broken tympanum with the angels holding the gilded cross, the rays of light radiating toward the painted and gilded stucco vault, the work of Pompeo Gentili.

And even in the midst of this display, this apotheosis of color, this chaotic and redundant jubilation, images of death abound, as in all seventeenth-century Roman churches. Almost every chapel holds the memory of a deceased person, a funerary memorial, a slab on the floor, and there is even a portrait, that of the Navarro economist Martín de Azpilcueta, which astounds with its ostentatious realism. And then there is a monument that seems almost to stop halfway between the seventeenth-century idea of death and what was to come later. In 1750, the Portuguese ambassador to the Holy See, Manuel Pereira Sampaio, had passed away; he had obtained the title to a chapel in Sant'Antonio dei Portoghesi: he had decided to dedicate it to the Immaculate Conception and have it redesigned, entrusting the task to Luigi Vanvitelli. So in here, among many, is also the architect of the Royal Palace of Caserta.

The construction was a bit of a tribulation, but the chapel was after all of a new conception, more orderly, more rigorous, though without renouncing the usual display of marble, the fluted columns in peach blossom with lots of gilded capitals, the serpentine mensa, the plinths in French yellow: thus a monument divided on the two sides of the chapel was made for the ambassador, alongside the altarpiece with theImmaculate Conception painted by Giacomo Zoboli. It was the work of one of the greatest sculptors of eighteenth-century Rome, Filippo Della Valle, who had imagined for Pereira Sampaio a monument that could celebrate him in two ways. And one that would be lauded as one of the best cenotaphs of his time. On the one hand, above his black marble urn, the celebration of the person: the portrait of Manuel Pereira Sampaio enclosed within a large medallion, the figure of winged virtue holding him up, books to account for his interests. On the other, the celebration of the professional: here then is the fame that blows its trumpet carrying the ambassador's feat in glory, a caduceus, a symbol linked to diplomacy as an attribute of Mercury messenger of the gods, which is held tightly by two hands, with the motto "Fide et consilio." And that's it. There are no gruesome images of death. There are no long obituaries. There is no momentum toward the afterlife. There is only the memory of a man whom fame will industriously work to get everywhere in the earthly world. There is an idea of death that is taking on different contours, modern contours. There is a new sensibility, the same sensibility that will lead to Canova, to Foscolo. To that candid glow in the midst of the boisterous procession of Baroque colors.