Searching for truth among the stones and paintings of the convent of San Francesco in Fiesole

In 1937, a young Albert Camus found a fragment of his truth in the convent of San Francesco in Fiesole. Amidst the silence of the cloisters, in the light of Tuscany and and amidst the works of art that reveal the human to us, we grasp the essence of the human condition. Beauty and Resistance. A new installment of the column “The ways of silence” by Federico Giannini.

By Federico Giannini | 06/07/2025 17:33

Albert Camus had found at the age of twenty-four a fragment of his truth among the cells of the convent of San Francesco in Fiesole. He had climbed up here, on the hill overlooking Florence, in September 1937, and spent a morning among the Franciscans, amid the smell of laurels, jotting down his impressions in notebooks, a passage that would later shape The Desert, a reflection on the human condition sparked by the light of Tuscany's landscapes, the faces of the women and men of this land, the poetry of the works of Giotto and Piero della Francesca. "I had stood for a long time in a little courtyard swollen with red flowers, sunshine, yellow and black bees. In one corner was a green watering can. Earlier I had visited the monks' cells, and seen their tables garnished with a skull. Now this garden bore witness to their inspirations. I had returned toward Florence, down the hill that descended toward the city offered with all its cypresses. That splendor of the world, the women and the flowers, seemed to me like the justification of those men."

Camus' courtyard still greets the visitor who arrives as far as San Francesco, after climbing the steep slope that begins behind Fiesole Cathedral. Already by the end of spring the sun is adamant, there is no space of shade coming to refresh those who decide to climb the short side, which is the most scenic but also the steepest and sunniest. On hot days better then to pass through the friars' forest, take shelter in the shade of the holm oaks, skirt the Etruscan walls of Fiesole that encircle the westernmost part of the city and wind up to the top of the hill, and find the small gap that leads into the Franciscan complex. One finds oneself in a meadow, in front of one's eyes the facade of the convent church, on the right an arcade, on the left a small room now used as a bar, refreshment point, and resale of typical products. Here, at one time, stood the acropolis of the Etruscan city. Then would come the Romans, and then, at the time of the crisis of the Empire, Fiesole would become one of the oldest and most important bishoprics in Italy. It was a prosperous city, launched toward a destiny that would see it as a rival city to Florence. The city of the mountain on one side and the city of the plain on the other. The noble ancient city, clinging to the hill and defended by its mighty Etruscan walls, and the young city that was growing and wanted to expand. The origins of the clash are lost in the darkness of a time that has not left us many traces and documents, but we can imagine that the war was inevitable. Ancient chronicles (Giovanni Villani, for example) tell of a first destruction of Fiesole by the Florentines in the year 1010, although modern historians have come to the conclusion that this first devastation is to be considered legendary. True, however, is the destruction in 1125, the date of Fiesole's final subjugation to Florence: after a three-month siege in the summer of that year, the Florentines got the better of the Fiesolians, entered the town, destroyed the castle and forced the inhabitants to take up residence in Florence. The site on which St. Francis stands is where the castle of Fiesole stood in ancient times.

It dates from exactly a century after the founding of the convent. It was 1225 when a first community of Benedictine nuns settled here on the top of the hill and dedicated their monastery to Santa Maria del Fiore. The first nucleus would later grow in 1339, when a wealthy Fiesole tailor, Lapo di Guglielmo, had the chapel added, still today dedicated to Santa Maria del Fiore, which can now be reached by descending down a very steep flight of steps from one of the cloister corridors. Then, again the usual munificent Lapo di Guglielmo, a few years later financed the construction of another complex, along what is now Via Faentina, at the foot of the hill: entrusting the project to the architect Benci di Cione Dami, the building was completed in 1355, and the nuns left the Fiesole knoll to move here, to the new convent which, in honor of its benefactor, is still called Santa Maria del Fiore a Lapo. Then came, toward the end of the 14th century, the Observant Franciscans, who enlarged the original building, making it take on its present conformation. Again thanks to a donor, the Florentine nobleman Guido del Palagio, who left the friars his entire inheritance. And towards the beginning of the 15th century the Franciscans were already inhabiting the enlarged convent. Named, of course, after St. Francis.

The church today is no longer what the Franciscans saw in ancient times. Camus, however, saw it as we do, since the appearance with which the church appears today to the eyes of visitors and the faithful is due to the renovations that architect Giuseppe Castellucci, the same one who built the headquarters of the nearby Bandini Museum, conducted between 1905 and 1907, giving the church its present neo-Gothic facies . The intervention had removed all Baroque additions as was the custom of the time, although even in those years Castellucci's ideas were questioned: his operations had been deemed too radical and arbitrary. It is a fact that that intervention gave San Francesco the forms we see today. Castellucci reopened the façade's rose window, redid the windows of the presbytery where new stained-glass windows made by the De Matteis firm were placed, designed the new high altar and also the side altars, all in the neo-Gothic style, as well as its front elevation, which has a simple gabled façade covered with 'a masonry face made of large irregular stone ashlars, over which open the fretwork rose window, with its twelve rays, and the portal surmounted by a frescoed porch (which is still the old one and still retains its sober decorative apparatus).

Probably it was enough for Camus to observe the exterior, it was enough to stroll through the courtyard, it was enough to smell the scent of the flowers to grasp that close, deep, strong bond that, according to him, somehow associated the girls who wandered around Florence in their light dresses at the end of the summer, the Franciscans of Fiesole who meditated on their little tables with skulls, and even the young men who spent all year under the sun on the beaches of Algiers. A "common resonance," he said. "If they undress, if they renounce, it is for a greater life (and not for another life). It is at least the only valid use of the word 'undressing.' To be stripped always preserves a sense of physical freedom, and this agreement of the hand and the flowers, this loving understanding of the earth and man detached from the human--ah! I would convert to it if it were not already my religion. No, it cannot be blasphemy, nor can it be if I say that the inner smile of Giotto's Saint Francises justifies those who have a taste for happiness. For myths stand to religion as poetry stands to truth, ridiculous masks placed on the passion of living." This undressing, this lightness, that of the Franciscans who reject the world, who renounce earthly goods, that of the boys on the Algerian beaches who in their natural nakedness, in their simplicity, do not undress on principle but live in the essentials, is a form of liberation from everything that prevents contact with a life lived more intensely, with a fuller life. There is not, even in the Franciscans' renunciation, an escape from the world. There is, rather, the intensification of an earthly experience.

Truth is then that which continues, that which resists time and illusions. It is, that of Camus, a physical truth, an immanent truth, the truth of the mortal body, of the pulsing of the blood, the truth of the flesh, the truth that must corrupt itself and that therefore takes on "a bitterness and a nobility," a truth to which it becomes difficult to look in the face. The poetry of art can then be seen as a form of consolation, as an escape from brutal reality, an escape to an unreal, silent, reassuring world. The paradox, however, is that art does not hide the truth: if anything, it shows it. It reveals it. It consecrates it. Art elevates reality to the rank of absolute truth, because art does not cover reality with veils: poetry, if anything, is ascertainment. The art that "from Cimabue to Piero della Francesca the Italian painters have raised among the Tuscan landscapes," says Camus, is "the lucid protest of man thrown upon a land whose splendor and light speak to him ceaselessly of a God who does not exist." Echoed in Camus' words is Heidegger's Geworfenheit , the condition of discovering ourselves thrown, cast out, abandoned in a world we did not choose. Human beings, however, do not resign: they protest, with their lucidity and dignity. And art, for Camus, is the highest form of protest, it is a "black flame," a flame that burns in the dark, that promises nothing, shows the human being for what he is: a mortal creature, capable of creating beauty.

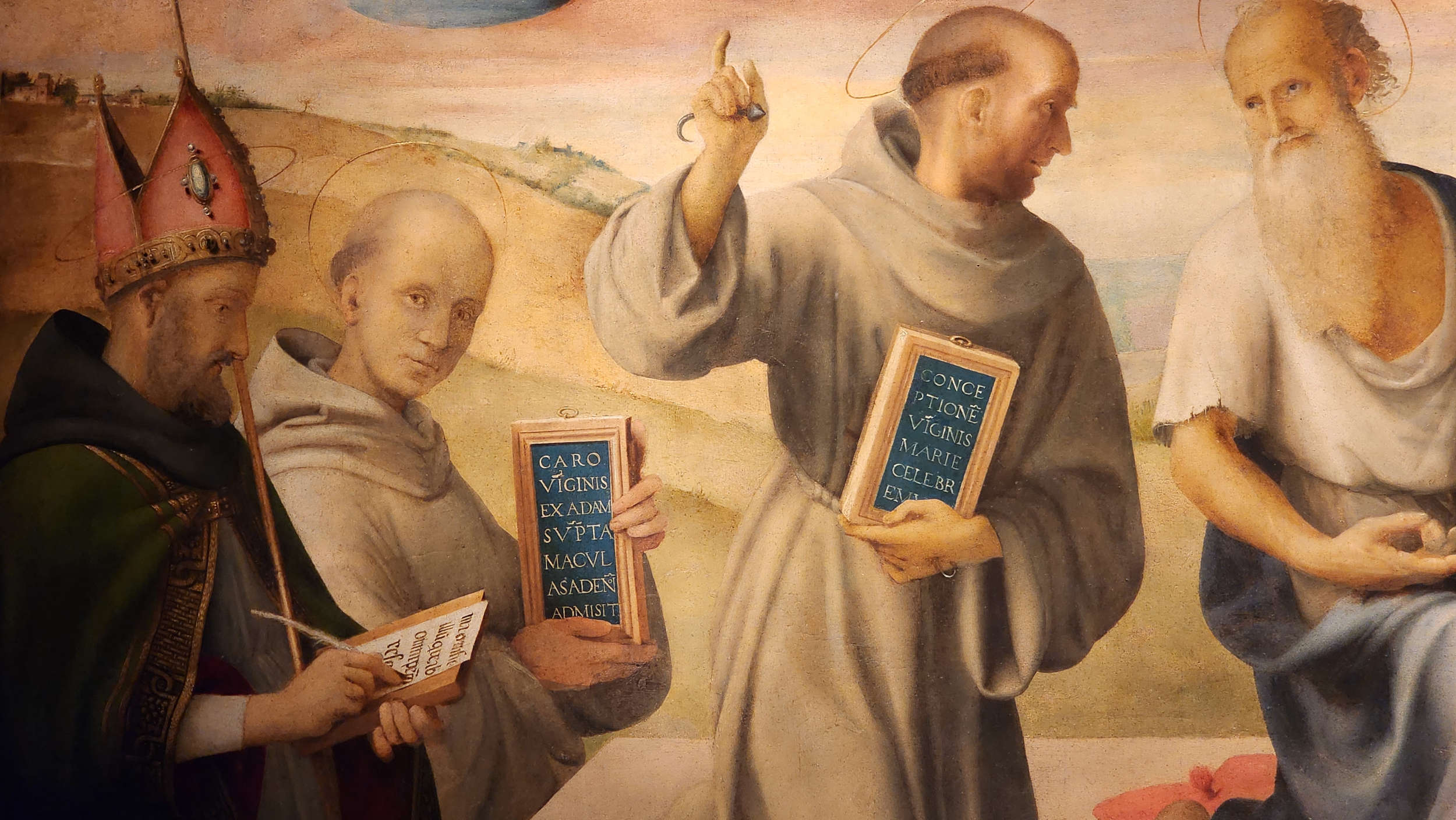

The church of St. Francis is, like all Franciscan churches, simple, sober, bare. On the altars, gold and azure poems on paneling remain. The Mystical Marriage of St. Catherine of Alexandria, a 14th-century work by Cenni di Francesco di Ser Cenni, is perhaps as close as Camus had in mind when he said that in those crowds of angels he had seen in the churches of Florence, in those infinitely recalculated faces, in those pensive hosts, he recognized a loneliness, he recognized the human condition expressed through the symbols of faith: very human faces caught in their existential isolation. Nearby, a beautiful Annunciation by Raffaellino del Garbo, which frames the sacred episode within a geometrically perfect serliana: at the top the roundels with the prophets Isaiah and Jeremiah announcing the arrival of Christ, the Tuscan landscape with river, village and bridge dominated by the mandorla in which the Eternal Father appears, the patron in the abyss, the angel and the Virgin almost extras of a mathematical scheme. Then there is the rebus of theAdoration by the Master of the Epiphany of Fiesole, an eponymous work by an artist who has not yet been identified, but who was working in late 15th-century Florence looking to the sweetnesses of Botticelli, here and there to the nervousness of Filippino Lippi, and above all to the finesse and marked linearism of Cosimo Rosselli, proposing a somewhat more schematic version. On the next wall is a splendid triptych by Bicci di Lorenzo, a Madonna and Child Enthroned flanked by St. Louis of Toulouse and St. Francis on one side, and St. Anthony of Padua and St. Nicholas of Bari on the other: late Gothic flourishes while in Florence the air was already full of Renaissance, a cascade of gold in a world that was now looking away. And then, further on, on the opposite wall, before turning our gaze to Neri di Bicci's Crucifixion placed on the high altar, in front of the Renaissance apse with its barrel-vaulted roof, we admire theImmaculate Conception which is among the lesser-known but no less interesting paintings by one of the most singular artists of the 15th century, Piero di Cosimo, whose apocryphal signature on the lower border, with an implausible date of 1480, someone affixed at a later date, as Berenson had already noticed in 1903.

Vasari cited the work in his Lives as the "tablet of the conception in the partition of the church of San Francesco da Fiesole" and judged it to be a "good little thing, sendo le figure non molto grandi." Actually, since there was no partition in the ancient church, we have to imagine that Vasari was wrong: already in the early 16th century, however, it must have been above one of the side altars. Piero di Cosimo imagined a composition divided into two registers: at the top, the Eternal Father raising his scepter over the kneeling Virgin, a scene that alludes, Gerardo De Simone has noted, "to the biblical episode of Esther and Ahasuerus, according to a parallelism that has become exemplary in the liturgical-devotional literature promoted by Sixtus IV: for the exemption of the capital law, reserved for Esther alone, análogon of the immaculist privilege but also, for the intercession with King Ahasuerus in favor of the Jewish people, for the reference to Mary's corredemptive role." The angels each bear a scroll: the one on the left identifies the Virgin with the bride of the Song of Songs, while the one on the right praises Mary's purity. In the lower portion, six saints hold scrolls and tablets: Augustine addresses the Virgin directly and asks her to magnify the God who preserved her from sin, St. Bernard shows a phrase from St. Peter Damiani ("the flesh of the Virgin taken from Adam did not admit the stains of Adam"), St. Francis calls for the celebration of the Immaculate Conception, Jerome shows a phrase from Paschasius Radbertus ("All that Mary did was totally pure, true and full of grace"), Thomas ofAquinas presents a passage from his Sententiae ("Mary is immune from all sin, original and actual"), and at the end, on the right, the theory of saints is closed by St.Anselm who, like Bernard and Jerome, shows a passage that was once thought to be his, while in his case it is to be attributed to one of his disciples, Eadherer of Canterbury ("I do not believe that one really loves the Virgin if one refuses to celebrate the feast of her conception.").

This celebration of the Virgin, exalted by the saints looking up to heaven, is an earthly construction, Camus would have thought. Those saints look to heaven, but they reveal a condition that is profoundly human. The Tuscan painters did not paint God: they painted their idea of God, a human idea. On a par with the works of mercy that Baccio Maria Bacci, between 1934 and 1935, painted on the walls of the sacristy, leaving here in Fiesole one of the most beautiful fresco cycles of the early 20th century, unjustly neglected by those who, dazzled by the gold of the 15th-century panels, devote the residual part of their visit to these lunettes. Also from these images seems to emerge that "wild, soulless grandeur [...] to be understood as a decision to live" that Camus found in Piero della Francesca's Risen Christ . His truth had appeared to him in the light of a summer spent among the hills of Tuscany, the same light that today tens of thousands of people, tourists, travelers from all over the world still see resting on the city, on the palaces, on the coasts that climb the hills, on the paved streets, the same light that enters the churches and shines on the golds of the ancient tables.

Inside the church of San Francesco, it's a weekday in late spring, tourists keep arriving who have made it all the way up, most passing by the street that juts out giving a view of all of Florence. Before the last ramp, there is a painter who has set up his frame in the shade of a tree and tries to capture the view that stretches to the hills of Oltrarno. So many prefer to brave the midday sun and see the city from above, rather than go through the friars' forest and deprive themselves of the magnificent view. Then, they stop on the courtyard wall to have a drink of water, refuel at the little bar open in one of the convent's rooms, take a few photos of the facade of St. Francis. They are all dressed for hiking, many have come up here with Nordic walking poles. Probably most wanted to get away for half a day from that bog of sweat and flip-flops that is Florence in high season. Then they enter the church and pause in the silence, among the golds of the tables. A lady, perhaps Polish, starts to pray. A small contingent of tourists, accents from the Veneto, lay down their cameras and contemplate in silence the Master'sAdoration of the Epiphany. A German girl holds the hand of her child, a half-foot little fellow with blindingly blond hair. A couple enters, camping backpacks on their shoulders, they start taking pictures. In the solitude of St. Francis, among the beauty of a landscape that does not promise salvation, in the midst of a Gospel that is made of matter, of stone, of sky, of trees, among the works that continue to make that black flame of protest burn, each perhaps seeks his truth.