If a city is told through art that is public gesture. The example of the Voyage à Nantes

The Voyage à Nantes is a public art event that, since 2012, animates the streets and squares of the French city. Here, art is understood as a tool that does not impose itself, but allows itself to be crossed. A gesture that changes the way we are together. This is how in Nantes art becomes a collective gesture: the reportage by Francesca Anita Gigli.

By Francesca Anita Gigli | 17/07/2025 16:56

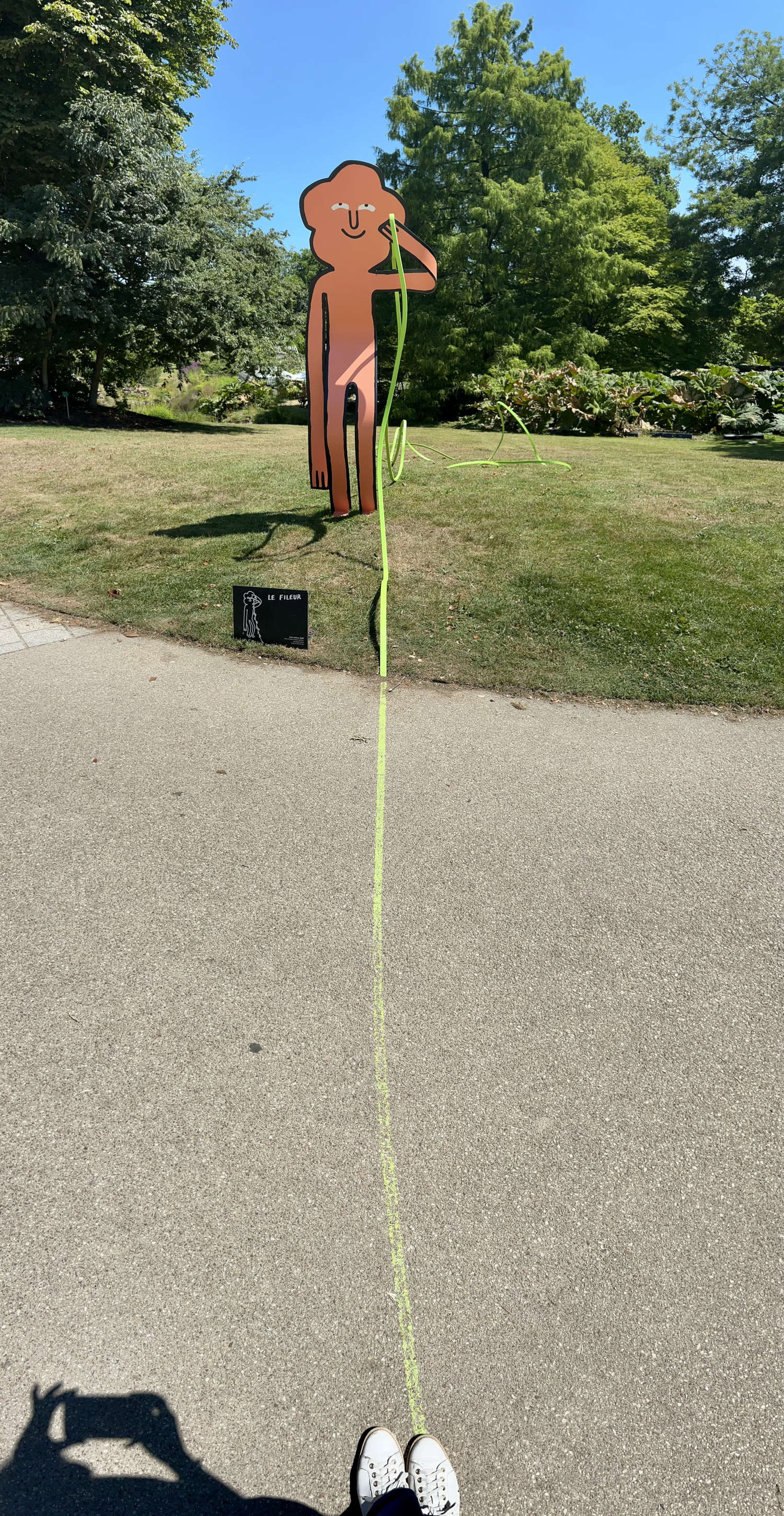

In Nantes, there is a green line that winds across the asphalt like an uncovered, tense, pulsing vein that invites detour, slanted step, and the lopsided geography of desire.

It starts from a garden populated by imaginary creatures, stretching colorful threads among the branches and climbing shiny ribbons that break the sunlight into sharp reflections. From there, from the Jardin des Plantes, the line begins to flow, stretching between sidewalks, skirting marginal neighborhoods, lapping buildings in silence and forgotten courtyards. Sometimes it climbs a blind staircase, bends under a bridge, stops in front of a work that seems almost a mistake: a sculpture that seems to say nothing, a dripping wooden animal, a mother ship landed by mistake in the heart of the city.

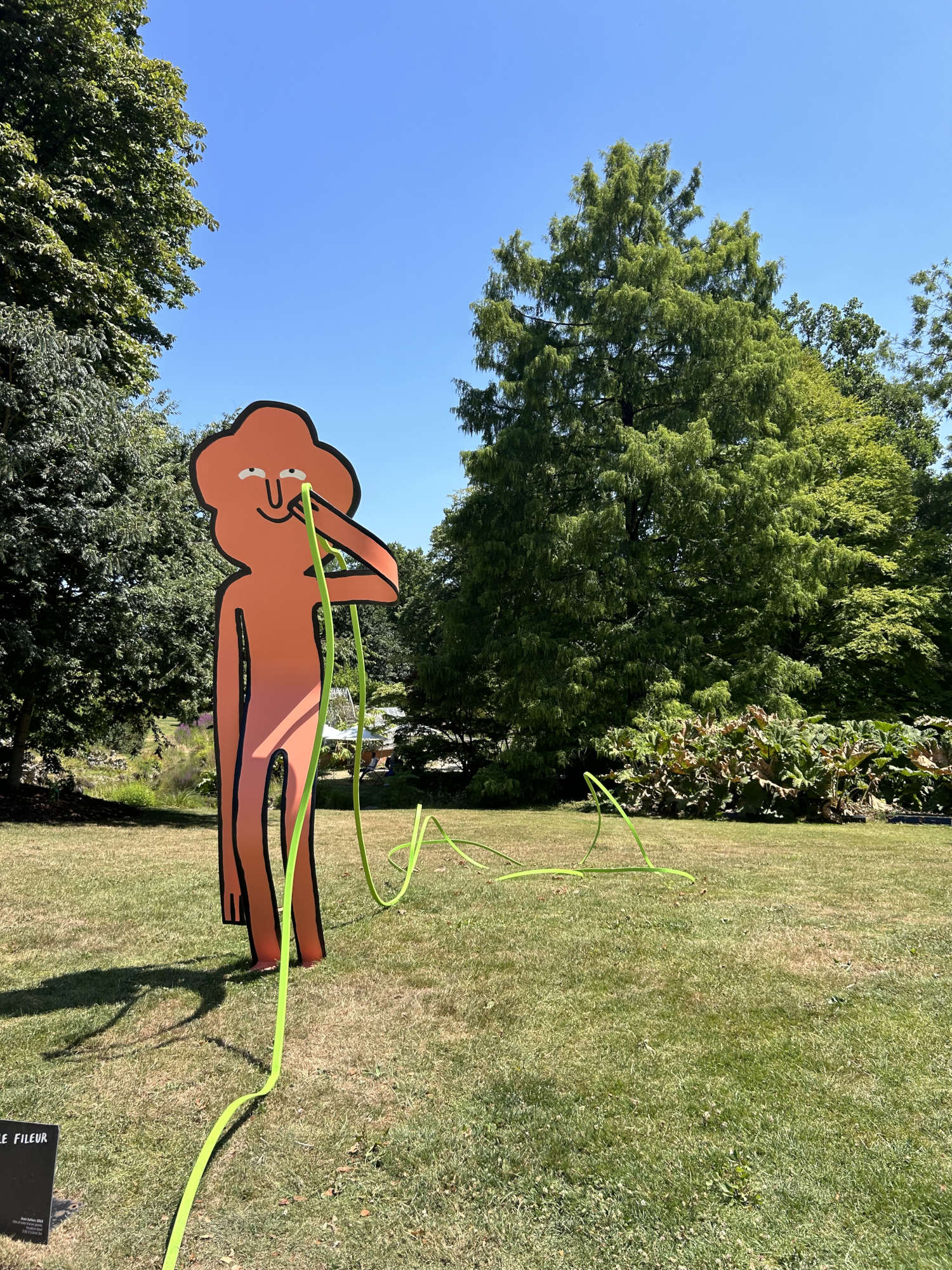

Once again this year, from June 28 to August 31, 2025, Voyage à Nantes invites you to walk this line drawn on the asphalt, to follow it with your body even before your gaze, to inhabit it as you inhabit a possibility. Some works change, others multiply, many vanish, but some remain. Éloge de la transgression, in the Cours Cambronne, continues to question us from the height of its semi-empty pedestal. Or again Jean Jullien with Le Fileur, weaving its green thread among the flower beds, as if drawing alternative paths for those willing to look down. To follow this line, then, is to unclutter the gaze and, above all, to question the very idea of work and public space. At each bend, time bends, the landscape opens up, and art emerges only if you agree not to recognize it right away. Getting lost along the path does not mean reaching, but accepting that a city can tell its story in this way as well: not by showing its masterpieces and places to be quickly ticked off on an imaginary list, but its edges, its folds, its interstices. Then it changes the pace, the rhythm, the gaze. Even the breath. Because, and this is very rare, the city does not offer itself as an exhibition. It is offered as a gesture, as a hypothesis; as a slow choreography that engages the body even before thought. It is, in the end, a subtle device for shifting the center, for redistributing attention and creating new possibilities. And perhaps this is where art stops being an object, and becomes relationship again. Something that happens between. Between one step and the next, between the beholder and that which does not allow itself to be explained, between your presence and a city that allows itself to be read in fragments, without the need for a unified sense.

It is precisely within this gentle drift, in this lucid suspension that the step imposes when one abandons haste and lets the walk become part of the work itself, that another possibility of thinking about urban space and its aesthetic dimension manifests itself, no longer as an inert backdrop nor as an open-air gallery, but as a porous system of relationships, as a living fabric in which art does not happen alongside life, but through it, contaminating it and allowing itself to be contaminated.

And in such generous openness to involvement lies a critical threshold, for not every participation is fertile and, more importantly, not every relationship produces transformation. Art historian Claire Bishop reminds us of this rigorously, warning that the sociality proposed by certain relational art runs the risk of slipping into a sham of inclusion, where the audience's presence is foreseen, registered, channeled, but rarely interpellated in depth and rarely called upon to confront the friction, disagreement and asymmetry that every authentic aesthetic experience brings with it.

It is precisely here, perhaps, that the city of Nantes chooses a different path since, instead of choreographing participation, it disperses it, scatters it along a line that neither protects nor orders, but invites misalignment, error, and the constant repositioning of the gaze. And in this continuous slippage of meaning, in the lack of fixed points, a form of temporary citizenship emerges, made up not of possession of space but of conscious crossing, of micro-actions that affect the city as a new form of writing. A writing that is read with feet, with sore knees, with shortening breath, with weather that changes a thousand times a day, with time that stretches, and that restores to the city not a function, but a question: who are you, when you stop claiming to have only one face?

Herein lies perhaps the most political gesture of public art, which is not the occupation of space, but its openness; not monumentality, but the margin; not visibility, but possibility. Here then, at times, the green line diverts silently and skims a side portal threading its way into a wide and collected courtyard where the stones tell of centuries of layering and passage. TheHôtel de Briord, once an aristocratic residence, then home to the École des Beaux-Arts from 1904 to 2017, now holds in its stone belly a work by Gloria Friedmann entitled Absurdistan. The introductory panel is clear, the access simple, the context carefully curated. And yet, in this very strict simplicity, Absurdistan builds a threshold.

Eleven life-size human figures gather around a central presence composed of cables, wires and eerie fragments of electronic memory. The mechanical body at the center has the density of an extinguished core, of an intelligence collapsed in on itself, yet held by all the others, as if each figure depended on that timeless, faceless mass. None of the characters on stage performs a full action, but each holds back a tension, a possibility, a frozen trajectory. The impression is that of a collective halt, a cruel pause in which the future remains held in the hands, never having a chance to fully manifest itself. Gloria Friedmann, with a gaze at once caressing and ruthless, constructs a silent theater in which the human being (this strange terrestrial biped who has learned to walk, rise and transform the world) finds himself hooked to his own technological evolution, connected to incessant streams of data, images and commands, made ever more transparent and ever less interpretable.

She creates motionless, suspended human figures, as if stranded in an unstoppable process that only makes them dependent. The German sculptor does not recount a dystopian future, but an already compromised present, in which technology is no longer a tool but an environment, an invisible membrane that connects, transforms and anesthetizes us. Bodies, in the installation, do not interact but suffer. They are intermediate creatures, already hybrid, already consigned to another form of existence in which technology is the very condition of our being in time.

A scene like this finds a powerful theoretical antecedent in Günther Anders and his 1956 book Man is Old-Fashioned. Anders lucidly describes the "Promethean shame" that consists in the increasingly widespread feeling that human beings experience when faced with theefficiency of their own technical creations. The machine is repeatable, precise, eternal. Man is not. Thus there arises a growing gap between those who produce and what is produced, a temporal divide between the mind and things. Man ends up feeling outdated, outmoded, inadequate, and this non-synchronicity between the individual and the technical world generates an existential paradox. Humanity is no longer able to understand or control its own artifacts because technology, Anders says, overpowers us with an impersonal efficiency, with a perfection that makes us clumsy and guilty. Hence a reversal of ends and means: we no longer use technique for our own ends, but are used by it for ends that elude us. In particular (and here, on this point, Anders' thought is prophetic) through the media, advertising sequences, and apparatuses of persuasion that create a world of phantom images, a serial, unreal world to which the individual responds passively, compulsively, obsessively.

In Absurdistan this disorientation is not shouted, but sculpted in the silence of postures. The figures are still, yet fragile. As if their stillness is already a form of surrender. A gentle, even elegant, but final surrender. A kind of inertia is staged, so aesthetic and so composed, in which a new and restless form of loneliness is glimpsed. Each figure is connected, embedded in a central body, in a network that seems to embrace but actually isolates; in which connection is not relationship, and proximity is not enough to bridge the gap, not enough to bridge the loneliness. We are part of a system that includes us but does not recognize us, that processes us as data but forgets us as people. In this sense, Absurdistan is also a map of our new cognitive dependencies: a society in which memory becomes externalized, judgment relies on algorithms, and artificial intelligence that assists us, anticipates us, interprets and eventually drains the very effort of thought. Everything becomes simpler, faster, more perfect. And we, at the heart of this perfection, remain alone. Impeccable, but alone.

Further on, near the station, as the pace lengthens between houses and storefronts, the green line creeps into the Rue de Richebourg and changes tone. It does not become more subtle, it does not try to disappear but becomes the bearer of another rhythm, of an irreverent vibration. In the courtyard of the Lycée Clemenceau stands Romain Weintzem's La Mauvaise Troupe: a band of human-sized sculptures, disguised as soldiers and overwhelmed by their own marvelous futility, mimetic figures holding monumental trumpets, drums and brass instruments as if they were parade weapons, marching silently against nothingness. Each body is motionless, but in the pose lives a restrained movement, a challenge still in progress. Everything in this installation breathes the precise will to challenge the codes of power: military postures deform into play, camouflaged bodies lose authority, fanfares turn into instruments of subversion. There is no trace of glorification, no documentary intent as La Mauvaise Troupe does not tell the story of war, but mocks it, defuses it, exposes it as self-weary theater.

The artist Weintzem's gesture is rooted in the very soil of the city, in the stubborn memory of that high school where, in 1913, a group of students, including Jacques Vaché, published the magazine En route, mauvaise troupe!: a single issue printed in 25 copies, a single issue, yet so laden with verse, invective and irony so cutting that it cost some of its authors expulsion. Inside those pages, later banned, a voice took shape that would become decisive for surrealism, a voice that rejected patriotic rhetoric, that chose dream instead of order, insolence instead of discipline. Romain Weintzem returns to that same courtyard with a work that is not simply memory, but living legacy.

Everything is held in precarious balance: the poem by Verlaine that titles the magazine ("To the street, evil troop! / Go, my lost sons!"), the faint shadow of Breton, the latent presence of Vaché as the silent detonator of an entire generation. Each figure on stage is a caricature of the mask of power, a visual twist that brings war back to its theatrical nakedness, its drained gesture, its obsession with form. Here, each musical instrument held like a rifle says exactly that: sound can overpower command, disorder can become score. It is no accident that Weintzem chooses precisely the musical instruments typical of military bands (brass, bass drums, trumpets) and turns them into scenic, ambiguous, defused objects. In this way, the artist amplifies the paradox inherent in the very tradition of fanfares as music for war, rhythm for order, sound for obedience. But in La Mauvaise Troupe that order is broken, the sound remains mute, and the music becomes only a simulacrum of a discipline that no longer commands anyone. What on the surface is only play or caricature, actually sinks into a hard, real, precise memory: the boys who in 1913 founded the magazine En route, mauvaise troupe! were, all of them, enlisted in World War I. Some did not return.

The anarchist gesture of publishing an anti-militarist school paper turned into the fate of an entire generation: the patriotic rhetoric overwhelmed them, the school trained them to die. And so La Mauvaise Troupe becomes a counter-march, a secular rite of resistance, a choral sculpture that offers itself not as an explanation but as an exhortation. To laugh, yes, but with awareness. To remain unarmed, also, but with intention. And to walk together, even out of time, even without purpose, even if only to not let the pace be decided by others. And in this courtyard, which could be any courtyard, behind a school that could be any school, La Mauvaise Troupe forces us to remember that every war also begins this way. With a band that plays, with a hymn that trains the ear, with a uniform that aligns bodies even before thought.

Then something even different happens. The green line crosses the Parc des Chantiers and opens onto a landscape that seems to have emerged from another time, or from a barely sketched collective dream. There is a silvery sphere, soft, perforated with craters, a huge moon lying on the ground, ready to be inhabited. We will walk on the moon, say Détroit Architectes and Bruno Peinado, and there is only one real, physical, sensory invitation here; that of climbing, bouncing, lying down, looking, inhabiting. To take all the space. As much as it takes.

Bodies hover for a few moments, slow down, sway, slip into a state of sudden suspension that resembles not performance but abandonment. And in that abandonment, which asks for nothing and yet returns everything, a different idea of public space takes shape that becomes, simply, pause. A place that is not only traversed, but that heals, as psychiatrist Paolo Inghilleri recounts in his essay I luoghi che curano, because it is capable of accommodating inner transformations, of offering a threshold between intimacy and the world, of hosting experiences that seek meaning rather than the utility of existing.

And as we lie or jump in the silver seas, under a sky that seems closer, something also changes in the way we think about ourselves. For an instant, even a brief one, the body stops weighing, time retracts, thought slackens. And in that instant a possible space opens up for care, for suspension of duty, for imagination that does not evade but grounds. For the places that heal are those that allow one to construct meaning, to recognize oneself as part of a larger rhythm, to inhabit the world without having to immediately explain or modify it.

Yet We Will Walk on the Moon is not a "beautiful" work in the strict sense, and perhaps not even a memorable one if thought of only in its form. It does not have the formal power of a sculpture, nor even the visionary intensity of a conceptual installation. Yet it works. It works because it transforms a marginal area of the city, a forgotten bend between the construction sites and the river, into a point of convergence where families, students, the elderly, bewildered tourists, screaming children, tired fathers, educators and kids who have arrived from elsewhere meet. It works because it does not impose meaning, but lets it emerge from the bodies that inhabit it. In a city that bears on its shoulders the heavy memory of colonialism and triangular trade, We Will Walk on the Moon is not an escape, but a concrete reappropriation of urban space, a minimal but tenacious action that rewrites the way we take our place in the world.

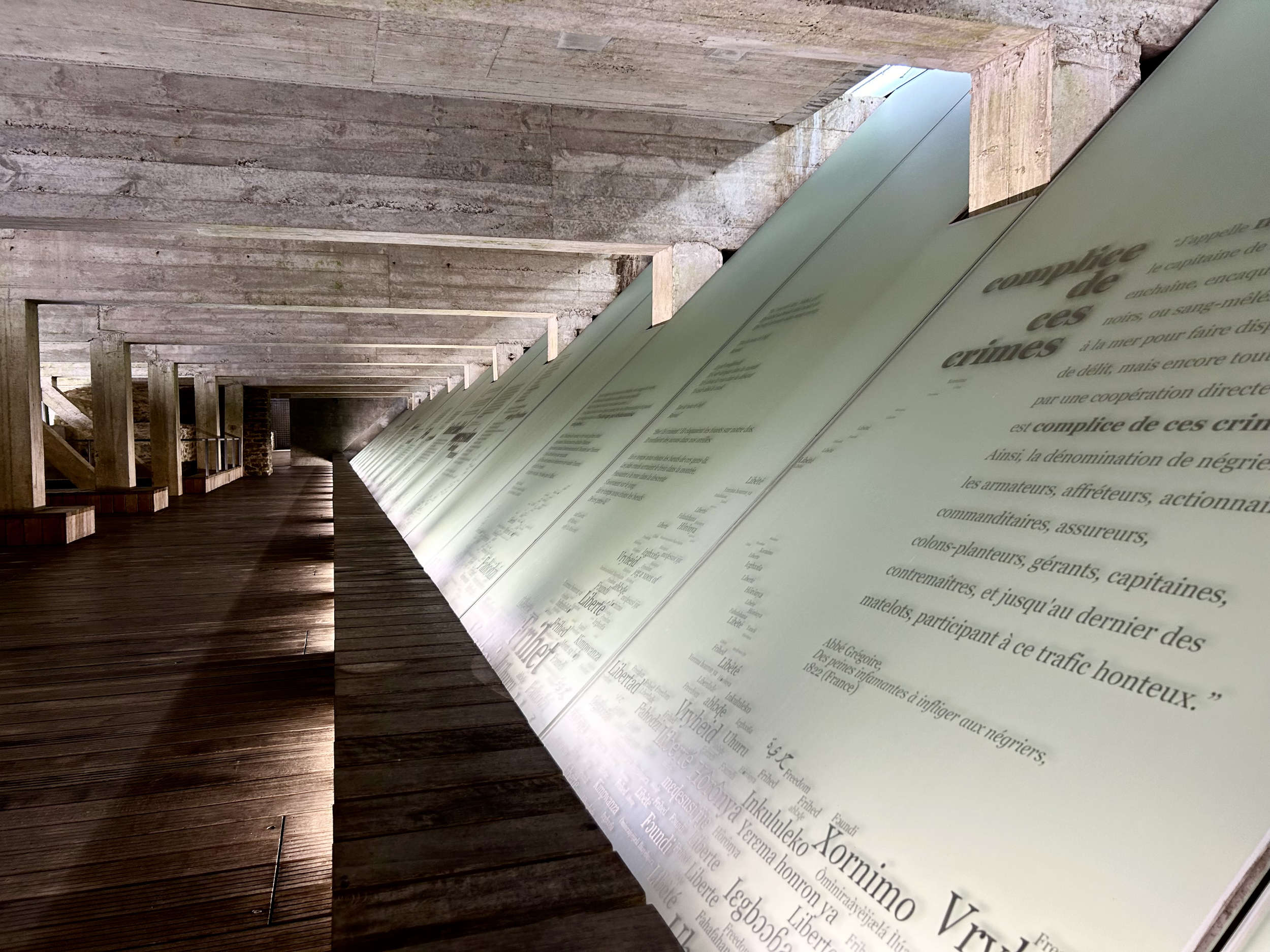

The green line, after stretching between courtyards, pierced moons and silent fanfares, leads toward the confluence of the Loire and the Erdre, where the island opens up like a geographical scar etched on the water. Here the streets become wider, the sounds rarefied, the houses barely leaning, but with such constancy as to seem like held breath. The whole area, built on sandy ground, rests on shifting, uncertain, sagging foundations. Entire period blocks, with their bourgeois facades, now show a visible deformation, a slight twist that strains the eye. Yet nothing collapses. Everything remains standing, shifted just enough to remind us that no stability is given forever, and that every city, if looked at properly, retains in its structure the mark of what it has passed through. This former island, once the beating heart of river trade, was also home to one of the central nodes of triangular trade. Nantes was one of the main European ports of the Atlantic trade: ships departed from here bound for Africa, laden with goods, then on to the Americas with human beings reduced to merchandise, and finally back to Europe with sugar, coffee, cotton, and fossilized blood in the form of capital. A memory that has not been erased, but for decades remained whispered, brushed over, compressed beneath the elegant architecture of the eighteenth century, as if the perfect lines of the buildings alone could contain the weight of a history removed. And further along the river, when the city begins to take on water and the footsteps barely tire, time contracts again. The Loire accompanies, flat and dense, with the calm that only great rivers can maintain, as if nothing could really disturb its flow. And right there, along the quai de la Fosse, one of the most intense spaces in all of Nantes opens up: the Mémorial de l'Abolition de l'Esclavage, which looks like an underground passageway and opens below ground level in a fissure between the city and its history. But the memorial begins earlier, on the surface with plaques set into the pavement that, illuminated at night, mark the approach like a procession, like a slow descent to the heart of memory.

Nantes, which, as we said, was the French capital of the slave trade, in the 18th century organized 43 percent of the transatlantic expeditions, and on this same pier sailed ships laden with bodies, names, and erased histories. And so the memorial exposes. It makes visible the unspeakable. Commissioned by the city and opened in March 2012, the Mémorial is the largest in Europe. The project was born out of an international competition won by Polish artist Krzysztof Wodiczko and Argentine architect Julian Bonder, and it stands as a political and poetic gesture that allows itself to be traversed in silence, among glass plates engraved with dates, routes, names of ships such as La Liberté and laws that made slavery the norm. In the heart of the Voyage à Nantes, where art plays, mocks, challenges, welcomes, the existence of a space like this one changes the measure of the passage. It reminds us that every crossing is also a gesture of choice: where to stop, where to slow down, where to listen. And above all, where to contain. Contain the weight, the doubt, the responsibility. Hold.

The river, meanwhile, continues to flow. Leaving the bank behind, when the light of the memorial fades under the earth and the surface becomes compact again, the landscape changes again. The asphalt stretches, the facades straighten, the windows line up in a bright discipline, and we enter another neighborhood of tree-lined avenues and austere buildings. This is how the Cours Cambronne appears, in all its architectural composure: an orderly promenade, designed for decorum, for civilized pause, for frictionless weather. And it is here, at the center of this apparent balance, that a dissonant gesture manifests itself. On a marble pedestal, where one would expect a bronze, definitive figure, stands instead a little girl immortalized in the act of climbing, or perhaps descending, precariously balanced on the plinth. Éloge de la transgression, Philippe Ramette calls it, and it is not about provocation. It is about displacement. Of minimal but decisive slippage. Of a measured deviation that is enough to crack the grammar of power.

Ramette, as always, works on the gap between sculpture and staging, between seriousness and paradox, between monument and abandonment. Here the homage is not to a man, to a hero, to a battle, but to a gesture. Or rather: to an attitude, to the act of disobedience.

The pedestal becomes a space of action. The pose becomes a question. It is not a question of whether he is ascending or descending, but of realizing that movement is already an act of thought.

In the neighborhood that more than any other in Nantes holds the city's noble memory (the neighborhood of composure, of uniform stone, of quiet symmetries), Éloge de la transgression introduces a crack that reminds us that every norm is a construction, and that every construction can be climbed. Even with grace.

So here the city, after showing its margins, its craters, its suspended moons, its memories sunk in the sand, arrives at the heart of its bourgeois elegance and, without raising its voice, without breaking anything, allows itself to be surprised by a little girl climbing a pedestal. She does not seem to be there to take its place, but to remind us that even emptiness has a right to its own statue, that even transgression has a right to its own space.

In the end, Voyage à Nantes is nothing more than an urban choreography that takes the city by the shoulders and invites it to dance out of time. It is a lopsided cartography that does not point toward a center, but opens along the edges, inside the fractures, between the sandy folds that make the houses tilt, without any need for unified meaning or linear narratives. The works traverse space and produce questions. And these questions are written on the walls, in the courtyards, in the trampolines, in the silences, in the changing materials, in the lights that come on after dark. Voyage is an urban gesture because it changes the way we are together. To watch, to detour, to walk without arriving. It is a collective gesture because it redistributes the possibility of feeling, even for a brief time, that the city can be other than itself: a place that heals, that disrupts, that laughs, that remembers with precision, that lets those who have not yet had a voice rise to the pedestal.

And, perhaps, it is just a way to be in the world without claiming to dominate it. A way to inhabit the city without expecting it to recognize us. A way to remain gentle strays, with pockets full of maps that lead nowhere, and the step that stumbles in the glass, in the water, in the moon. A way to be, if only for a few days, like certain off-key songs that sound good only on the street. And in that street, without any frame, something happens. Even if you can't tell what. Even if no one asks. But you live it. And you are not alone.