Japan in Tuscany: a journey through history, art and culture

A journey between Japan and Tuscany, from the first contacts in the 16th century to the comics of today: stories, art and crafts that unite two worlds only seemingly far apart. A living and mutual cultural dialogue.

By Redazione | 28/07/2025 14:27

Two worlds that, on the surface, appear as far apart as they can be: Japan and Tuscany. The land of the rising sun and the land of the Renaissance. Yet, Japan and Tuscany are closer than one might think, because they share ties rooted in a history that is made up of encounters, cultural exchanges, and mutual suggestions. Two worlds geographically distant yet united, meanwhile, by a similar sensitivity to art, to beauty, to harmony with nature. Japanese interest in Tuscany has deep roots, however, and has been fueled (especially since Japan interrupted, beginning in 1853, the sakoku, or its policy of isolation and closure to foreign countries that had begun in 1641) not only by the global fame of its art cities, but also by a genuine curiosity for its art, its traditions, its landscape, its material culture. And vice versa, Tuscany has long welcomed Japanese cultural forms with attention and respect, a circumstance that has helped build a rich and enduring intercultural dialogue that is still very much alive today.

However, the first contacts between Japan and Tuscany date back well before the 19th century. In 1585, the first Japanese diplomatic mission sent to Europe, which has gone down in history as theTenshō embassy, and consisted of four very young Japanese princes of the Christian religion (Itō Mancio, the head of the delegation, just 16 years old, accompanied by Giuliano Nakaura, Martino Hara, and Michele Chijiwa: it was not unusual for Japanese people of the Christian religion to have Western names), also touched on Tuscany on their journey, landing in Livorno on March 1 of that year: the young men were received by Francis I de' Medici, who gave them a tour of the capital Florence as well as Pisa and Siena. They stayed in Tuscany until March 17, when, from San Quirico d'Orcia, they departed for Rome.

Later, Florentine merchant Francesco Carletti (Florence, 1573 - 1636), the first private traveler to make the circumnavigation of the globe, was among the first Westerners to leave written records of his travels to Japan in the late sixteenth century. His chronicles, the Ragionamenti di Francesco Carletti fiorentino sopra le cose da lui vedute ne' gli suoi viaggi si dell'Indie Occidentali e Orientali come d'altri Paesi, describe with meticulous accuracy the Japanese society of the time, not without noting what might have seemed the most curious to the eyes of a Westerner (for example, Carletti insisted on the strong social hierarchy that resulted in relationships of total subservience to the point, the merchant recounted, that "many [...] by commandment of the king, or of their lords, kill themselves, and the like do the women, if their husbands tell them so [...] and this same authority have the superiors with their vassals, and the masters with their servants, and slaves.") The details on clothing are interesting: "They dress in silk and gold cloths of different painted colors, as bed sarge, or similar other kind of cloths, are painted among us, and those of the poor men are commonly of bamboagia cloth, also of blue, red and black, and for brown in the death of their relatives they use to dress in white. These clothes of theirs they baste them with said firm bale cloth mixed with a certain sort of fluff, which resembles silk, but softer, which is very approposite to keep warm in winter, which in these weights is not less full of rain, snow and ice, than it is infra of us."

During Japan's period of isolation, which lasted until the mid-19th century, contacts between Japan and Tuscany were completely interrupted. However, the country's reopening to the outside world coincided with a renewed interest in Western art and culture among Japanese elites. Tuscany, with its artistic heritage and craft tradition, soon became a favored destination for intellectuals, artists and collectors from the Rising Sun.

The modern age, the early collectors and artists who looked to Japan

The Meiji era, or the period from 1868 to 1912, marked the beginning of a strong interest among Tuscan collectors in Japanese art. In fact, the phenomenon of "Japanism" that swept Europe in the second half of the 19th century after the end of the sakoku found particularly fertile ground in Tuscany. Florence, with its tradition of patronage and collecting, became one of the most vibrant centers for collecting Japanese art in Italy.

Particularly significant was the activity of Frederick Stibbert (Florence, 1838 - 1906), an English art collector and entrepreneur who nurtured a very strong passion for Japan and in particular its weapons: even today theJapanese armory at the Stibbert Museum in Florence, the museum to which the collector devoted much of his energies, is one of the most important collections of Japanese weapons in the world, as well as one of the richest conspicuous outside Japan. In the armory are 95 complete suits of armor, 200 helmets, 285 swords and auction weapons, 880 tsubas (i.e., saber guards), and various accessories spanning three hundred years, with some pieces dating as far back as the 14th century.

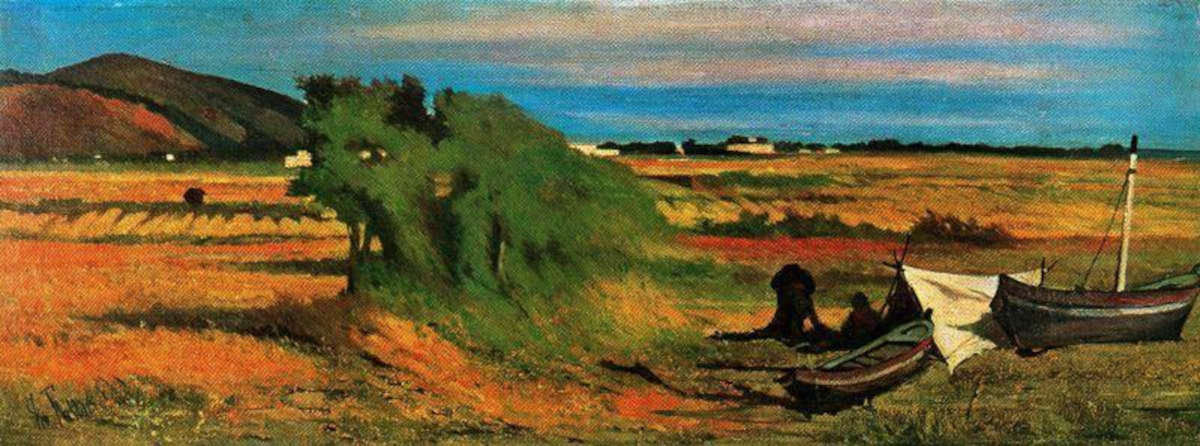

The interest was not purely commercial: in fact, the passion for Japan also invested art, according to trajectories that were well investigated in 2012 with the exhibition Japonism. Suggestions from the Far East from the Macchiaioli to the 1930s, curated by Maria Sframeli, Vincenzo Farinelli and Francesco Morena and held at Palazzo Pitti. Among the first to take an interest in Japanese art was, for example, Giovanni Fattori (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1908), who had the opportunity to see Japanese prints in Paris in 1875: Suggestions derived from Hokusai's ukiyo-e prints have been read in some of his works, such as the small canvas with the Rappezzatori di reti dating precisely from 1875, but also in works by Telemaco Signorini (Florence, 1835 - 1901), for example, the Sobborgo di Porta Adriana in Ravenna, which is perhaps the one that most closely attempts to approach the Nippon prints, or the painting Settignano (Impressions of the Countryside) that also recalls Hiroshige's Plum Blossom.

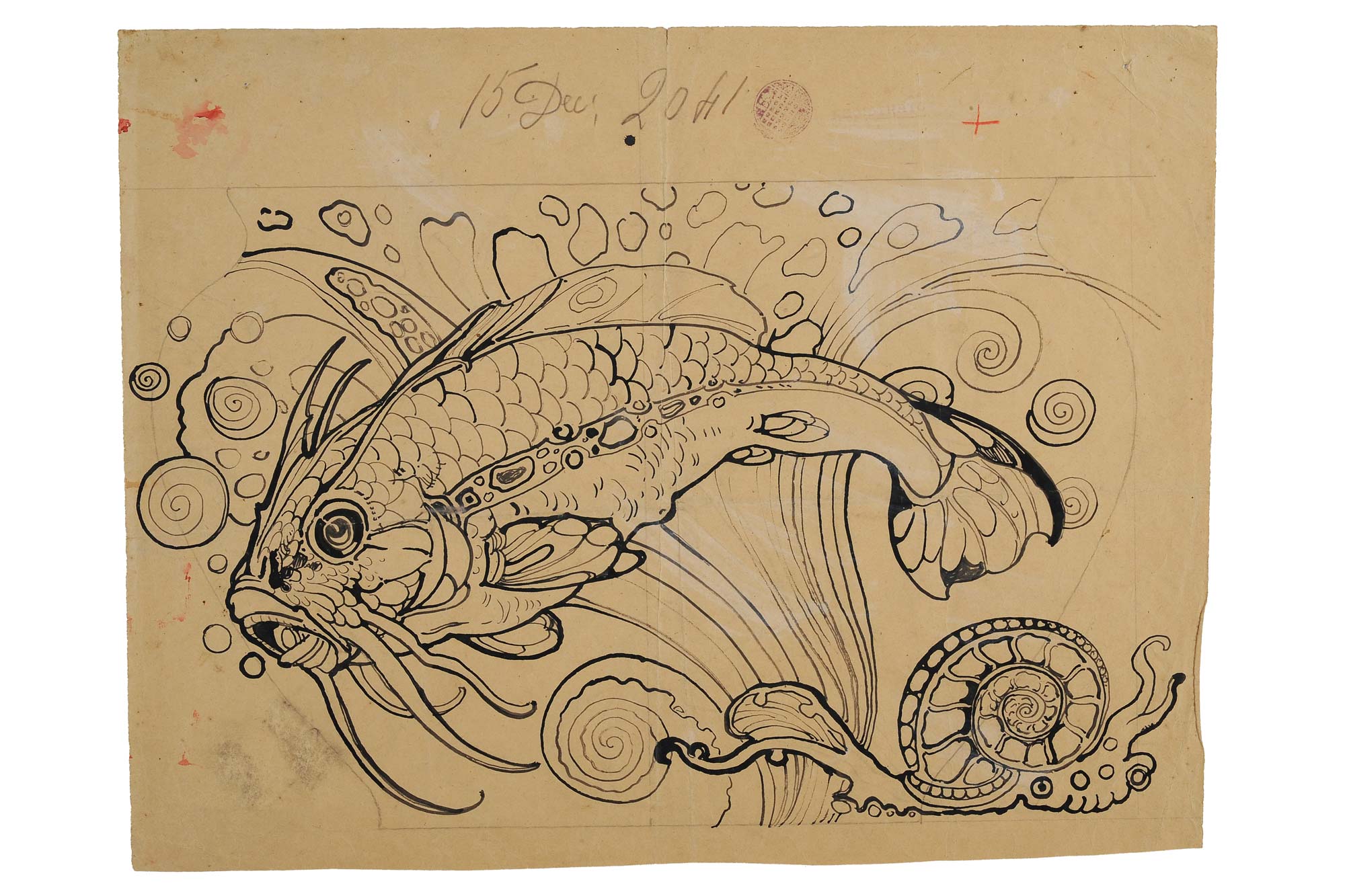

In the early twentieth century, this relationship underwent a further evolution. Plinio Nomellini, Renato Natali, Galileo Chini, and other leading figures in Tuscan art of the time developed a complex and articulate relationship with Japanese aesthetics that went far beyond the fashion for decorative Japanism. Galileo Chini (Florence, 1873 - 1956) was probably the most influenced by Japanese art among the Tuscan artists of his generation. His training at the family ceramic factory naturally led him to take an interest in Oriental decorative techniques, but his approach went far beyond superficial imitation. Chini studied in depth the compositional principles of Japanese art, particularly the use of empty space and dynamic asymmetry that characterize the Japanese pictorial tradition. His decorations and ceramics reveal a profound understanding of Japanese aesthetics, reinterpreted through a distinctively Tuscan sensibility and fused with Art Nouveau elegances (famous is his famous screen that represents perhaps the apex of this artistic dialogue). Plinio Nomellini (Livorno, 1866 - Florence, 1943), on the other hand, developed a more subtle relationship with Japanese art, mediated by his adherence to pointillism. The ukiyo-e prints toward which he harbored a certain passion suggested to him new possibilities in the use of pure color and formal synthesis. Certain of his landscapes, but also some of his portraits (e.g., The Girl with the Kimono) reveal the reception of certain cues, for example, a simplification of forms and a symbolic use of color that recalls the aesthetics of theukiyo-e masters.

A fundamental chapter in the relationship between Tuscan culture and the Japanese world is then represented by Giacomo Puccini (Lucca, 1858-Brussels, 1924) and his Madama Butterfly, an opera that was born in the cultural climate of early 20th-century Tuscany deeply permeated by interest in Eastern art. The composer from Lucca, who spent long creative periods at his villa in Torre del Lago, was immersed in an intellectual milieu where the passion for Japan was shared, and could not fail to offer suggestions to the great composer.

The dialogue between Japan and Tuscany today

In recent decades, the cultural dialogue between Japan and Tuscany has taken shape through a refined interweaving of Japanese art, craftsmanship, exhibitions, twinning and presence on Tuscan soil. This relationship, built on reciprocity and respect, is inscribed in a history of exchanges that touches different areas: from photography to ceramics, from cinema to crafts, to academic and civic exchanges.

Among the earliest initiatives in this regard is the twinning pact between Florence and Kyoto, signed on November 6, 1965, between then-mayors Lelio Lagorio and Yoshizo Takayama, and celebrated in 2025, on its 60th anniversary, with a ceremony at Palazzo Vecchio attended by current mayors Sara Funaro and Matsui Koji and Ambassador Suzuki Satoshi. The two cities, both UNESCO World Heritage Sites, share an artistic vocation and a focus on landscape preservation: the agreements include the exchange of restorers, museum curators, and master wood and silk artisans. The twinning was born as a result of the openings towards the East, in the 1950s, of Mayor Giorgio La Pira who, Sara Funaro recalled, "favored meetings with delegations from countries of the Far East, seeking to establish a constructive dialogue based on mutual respect and understanding between peoples; fundamental in this context are the relations between cities, seen not only as geographical entities, but as places where history, civilization and the destiny of women and men are realized, where it is possible to establish connections between distant peoples and build bridges of peace."

In the Tuscan territory, it is precisely twinnings that constitute a living channel of cultural interchange. Certaldo, linked for 40 years to the city of Kanramachi, often hosts Japanese delegations, with activities that enable dialogue between the two cultures. The academic and theatrical dimension takes a leading role in the Festival of Japanese Cinema in Tuscany, which since 2023 annually promotes the dissemination of Japanese film culture in Tuscany and more generally in Italy. And then, in 2025, the Osaka Expo was the setting for a week entirely dedicated to Tuscany: the Viareggio Carnival was presented to the Japanese public with shows, papier-mâché workshops and performances by Carnival artists, arousing excitement and curiosity among visitors. Italian operators reported how a significant number of Japanese actively participated in the workshops, attended the lectures with interest and welcomed the message of peace inherent in the Viareggio tradition.

In parallel, an important role is played by Lucca Comics & Games: in addition to the usual tributes to the masters of manga, the Japanese comic strip, who each year find in the Lucca event an important point of reference in Europe, recently, in July 2025, the organization presented the project of the future Museo Internazionale del Fumetto in Lucca, a new artistic pole dedicated to comics as a global language, under the cross-eye of the most influential cultural traditions of modern comics.

The dialogue between Japan and Tuscany remains a heterogeneous mosaic of experiences: exhibitions, festivals, twinning, handicrafts, Japanese language courses, and academic and cultural exchanges that build symbolic and concrete bridges, including through the work of various associations of Japanese culture in the territory, such as Lailac and IROHA, both based in Florence, which regularly organize activities outside the capital city as well, or subjects such as the Lucca Manga School, a Japanese comics school based in the city of walls. Traditional forms of Japanese craftsmanship, such as fabric, paper, the art of kimono or ceramic production, meet with the Tuscan identity made of manual skills, understated elegance, and historical memory. At the same time, Florence and Tuscany offer Japan the opportunity to express its artistic vision through photography, cinema, performing arts, and visual arts. A dialogue that shows the ability of two culturally distant regions to seek, discover and celebrate so that culture becomes a bridge and mutual nourishment.

Handicrafts and the transmission of knowledge

A particularly interesting aspect of the relationship between Japan and Tuscany concernstraditional crafts. Many young Japanese artisans choose to move to Tuscany to learn techniques that have been lost or overly industrialized in their country. Leatherworking, ceramics, weaving and goldsmithing attract hundreds of Japanese apprentices each year who are welcomed into traditional Tuscan workshops.

A subtle but valuable thread emerges in the Tuscan cultural fabric that links Japan to the region through crafts. Nipponese artists residing or operating in Tuscany (to whom we will reserve a dedicated article) have found fertile ground in the region, while numerous artisans have brought ancient traditional techniques here, reinterpreting them with contemporary sensibility and creating an authentic dialogue with local identity. Telling this presence means passing through paper workshops, marquetry workshops, jewelry studios, and cultural events where Japanese culture is not only celebrated, but inhabited, experienced, and put into practice.

One name among all emerges with particular clarity: Takafumi Mochizuki, known as "Zouganista," who in 2014 opened his own workshop in the Oltrarno. The name of his project, "Zouganista," enhances the Japanese word zougan (inlay), welded to the Italian root -ista, a symbol of cultural fusion(here an interview by Finestre Sull'Arte with Mochizuki). In Florence, Mochizuki carves and decorates reclaimed wood, commonly overlooked objects - shoe stands, hat blocks, coat hangers - transforming them into precious works of inlay, where Japanese aesthetics and Florentine craftsmanship coexist. He uses techniques such as kintsugi, the repair of broken objects by gilding cracks, to embellish rather than hide fragility, celebrating the beauty of imperfection. His workshop is both workshop, showroom and treasure chest of knowledge, exemplifying how Japanese artisan philosophies can relate to contemporary Tuscan craftsmanship

Another significant figure on the scene is Yuko Inagawa, a Japanese goldsmith who moved to Florence in 1993. After years of experience as an assistant at important local ateliers, she opened her own studio in 1996. She teaches and practices the techniques of investment casting, wax modeling, embossing, chiseling, 3D CAD design, gemology, jewelry histories and more. She works for world-class companies-including Tiffany & Co, Coccinella, Pineider-and is a constant participant in exhibitions.Her approach combines Japanese aesthetics with the history of Tuscan goldsmithing, making her a living, working example of cross-cultural craftsmanship. Long active in Tuscany, then, are artisans such as luthier Abe Jun, goldsmith Mari Yoshida Foglia, restorer Motoko Hasegawa, and leather goods designer Kyoko Morita, all names that have helped build bridges between Japanese and Tuscan techniques.

In their workshops, Japanese artisans offer not only objects, but also convey gestures, stories, gestures and rhythm. Every thread, every inlay, every mark on paper is a bridge between cultures. The activities of certain ateliers such as Washi-Arte, run by Meiko Yokoyama, an artisan specializing in washi paper who has long resided in Florence, or even calligraphy courses, and workshops such as Mochizuki's represent a form of implicit didactics, a way for Italy-and Tuscany in particular-to absorb the aesthetics, philosophy and spirituality of Japanese craftsmanship. Through these artisans, the dialogue between Japan and Tuscany takes on concreteness: an organic and meaningful presence that enlivens the Tuscan cultural fabric, enriching it with different but not conflicting sensory components. It is an encounter that produces beauty, sharing, mutual learning.

What began as an antiquarian interest in Japanese art has transformed over the centuries into a complex and articulate cultural dialogue that touches all aspects of human creativity. The mutual attraction is not based on passing fads or superficial interests, but is rooted in deep aesthetic and spiritual affinities. The search for beauty, attention to detail, respect for traditional craftsmanship and the ability to innovate without losing the link with the past are elements that unite the two cultures and explain the duration and intensity of this relationship. Today, the Japanese presence in Tuscany is no longer that of outside visitors who come to admire others' beauty, but that of active participants in a shared creative process. This two-way exchange has created over time a network of personal and professional relationships that goes far beyond institutional relations and constitutes the real wealth of this cultural dialogue.