The church of San Lorenzo in Lodi, where time has carved layers of memory

In the church of San Lorenzo in Lodi, time has settled like color on color: Renaissance frescoes, spectacular 16th-century stuccoes, medieval memories and forgotten fragments coexist in a unique weave, a mirror of the city and its artistic and spiritual history. A new article in Federico Giannini's "The Ways of Silence" column.

By Federico Giannini | 21/09/2025 13:40

We know from his notebooks that Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselle, in 1866, was in Lodi. For a field study, basically: a survey of everything that would flow first into the History of Painting in North Italy, written with Joseph Archer Crowe and published in 1871, and then into the History of Painting in Italy. Two founding texts of modern art criticism. We know that, in Lodi, Cavalcaselle visited everything there was to visit. He was especially interested in the works of the Piazza, the dynasty of Lodi painters who between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had started a lively, significant local school with results that would involve large areas of Lombardy. We know, due to the fact that his considerations later flowed into the History of Painting in North Italy, that Cavalcaselle had also pursued an obscure late fifteenth-century painter whom he had renamed "Giovanni della Chiesa," a name that has stuck to this "Maestro Giovanni" indicated by the sources and whose full name we still do not know. He had then found him inside the church of San Lorenzo, believing it to be his, and his brother Matteo's, very composed Nativity that one encounters in the first chapel on the left as one enters. A fresco whose "extraordinarily accurate execution" Cavalcaselle had appreciated, an exquisite work by one of those many petit-maîtres who at the time s'roamed the Po Plain, covering churches, mansions, cathedrals with paintings, and who today have plummeted into oblivion, partly because they left little behind, partly because little interests us now. They are there. On the peeling plaster of provincial walls, inside the musty halls of a barred palace, in the fragile silence of a dark church, fragments of a society that attached fundamental importance to art, faded traces of a past that today is good at most for a few guided tours.

The chapel that houses this substantially forgotten Nativity (for those who show caution and consider it generically a work of the "Lombard school," Cavalcaselle's attribution still applies), and which since the 1950s has become the baptistery of the church of San Lorenzo, has undergone many changes over the centuries: today we see the results of the work that the Confraternity of the Conception, the ancient owner of the chapel, commissioned various artists and architects between the 16th and 17th centuries with the idea of updating its appearance. The result was a pastiche of 16th-century grotesques and Baroque stuccoes that also obliterated the frescoes on the back wall: only a few remnants can be seen today. For those who want to get an idea of what art historians mean when they speak of "layering," the chapel of the Baptistery of San Lorenzo in Lodi offers perhaps some of the most concrete evidence to be found around Lombardy. The Nativity itself, wanting to go into detail, is no longer in its place: in 1970 it was snatched up by Pinin Brambilla, the restorer to whom we owe the memorable intervention on Leonardo da Vinci'sLast Supper in Santa Maria delle Grazie, was transported on cardboard and then rearranged there, in its chapel, in the center of the seventeenth-century altar. But the whole church of San Lorenzo is a continuous, overwhelming accumulation of images that seem to want to contradict each other.

There are, meanwhile, the reused materials. Walking around the aisles, one will easily notice some strange, ruined, irrelevant capitals: these are the ones that Lodians recovered from the rubble of the Roman Laus Pompeia , razed to the ground by the Milanese in 1158. Present-day Lodi was founded on August 3 of that year by Frederick Barbarossa, not far from the ancient city that had been destroyed and become a kind of huge open-air quarry. The construction of San Lorenzo had begun the following year, and the parishioners are keen to point out, between history and legend, that the work finished before that of the Duomo, which had begun the year before, at the same time as the founding of the city: San Lorenzo is therefore, in all probability, the oldest church in Lodi. Then there are the survivals. A pair of frescoes on the columns dividing the nave from the side aisles: a 16th-century Madonna and Child with St. Anne, and a Madonna in Sorrows with the Dead Christ , which instead seems earlier and repeats an iconographic pattern quite common in the Po plain. Along the archway of the chapel of the Crucifix are frescoes with the Fioretti di san Francesco that a donor, a certain Margherita Sangalli Carpani, had commissioned in 1565. Here and there passages of fourteenth-century frescoes, sometimes in situ, sometimes torn off and displayed as if they were paintings, the same fate, moreover, suffered by the great fresco of the Madonna and Child, Saint Lucy and Saint Catherine of Alexandria that Francesco Carminati, known as Soncino, a pupil of Piazza, painted between 1540 and 1550. And speaking of tears, also on display in the counterfaçade is the sinopia of the Nativity torn by Pinin Brambilla: a rather rare occurrence, that of seeing the torn fresco and its sinopia in the same place, inside a church.

Cavalcaselle had not lingered on the second chapel on the left, which was probably of little significance for what he was looking for, despite the presence of Bernardino Campi's large altarpiece, signed and dated 1574, a Pietà that is also among his most interesting things, with the pose of the Virgin and child that is almost identical to that of Michelangelo's Vatican Pietà , so much so that Campi's work would later be copied and imitated in turn. If you look up toward the center of the vault, you will notice an aristocratic coat of arms: it is that of the Vistarini, the family that owned the chapel, a dynasty at the center of the events that affected Lodi in the 16th century. Their palace overlooked Corso Vittorio Emanuele, the ancient Corso di Porta Regale, and looks today with the heavy renovations to which it was subjected in the seventeenth century, when it was purchased by the Barni family. It still bears the name of the Vistarini family, however, the palace overlooking Piazza della Vittoria, which in ancient times must have formed one with that of Porta Regale, a large residential complex. Today it is a shadow of what it must have been at the time; it also appears conspicuously curtailed on the left side, but in part it still preserves the appearance it must have had at the time of Lodovico Vistarini, a condottiere who fought for Milan, for the Empire, for Venice, for Genoa, and who earned the title of pater patriae for having saved his Lodi from the assault of the violent Fabrizio Maramaldo, who was deployed, like Vistarini, in the ranks of the empire. That had been in 1526: Vistarini, unwilling to see his city subjected to devastation and looting, and clamored by his fellow citizens, rebelled against the authority of the empire and, in an abrupt about-face, sided with his adversaries, the Venetians, to whom he opened the gates of the city, enabling them to repel the imperial assault. The salvation of Lodi cost Vistarini accusations of treason (from which he tried to exonerate himself by saying that he had decided to take leave of the emperor before that episode) and even a duel with another condottiero in the pay of the Empire, Sigismondo Malatesta, who was, however, defeated and humiliated by the Lodi man.

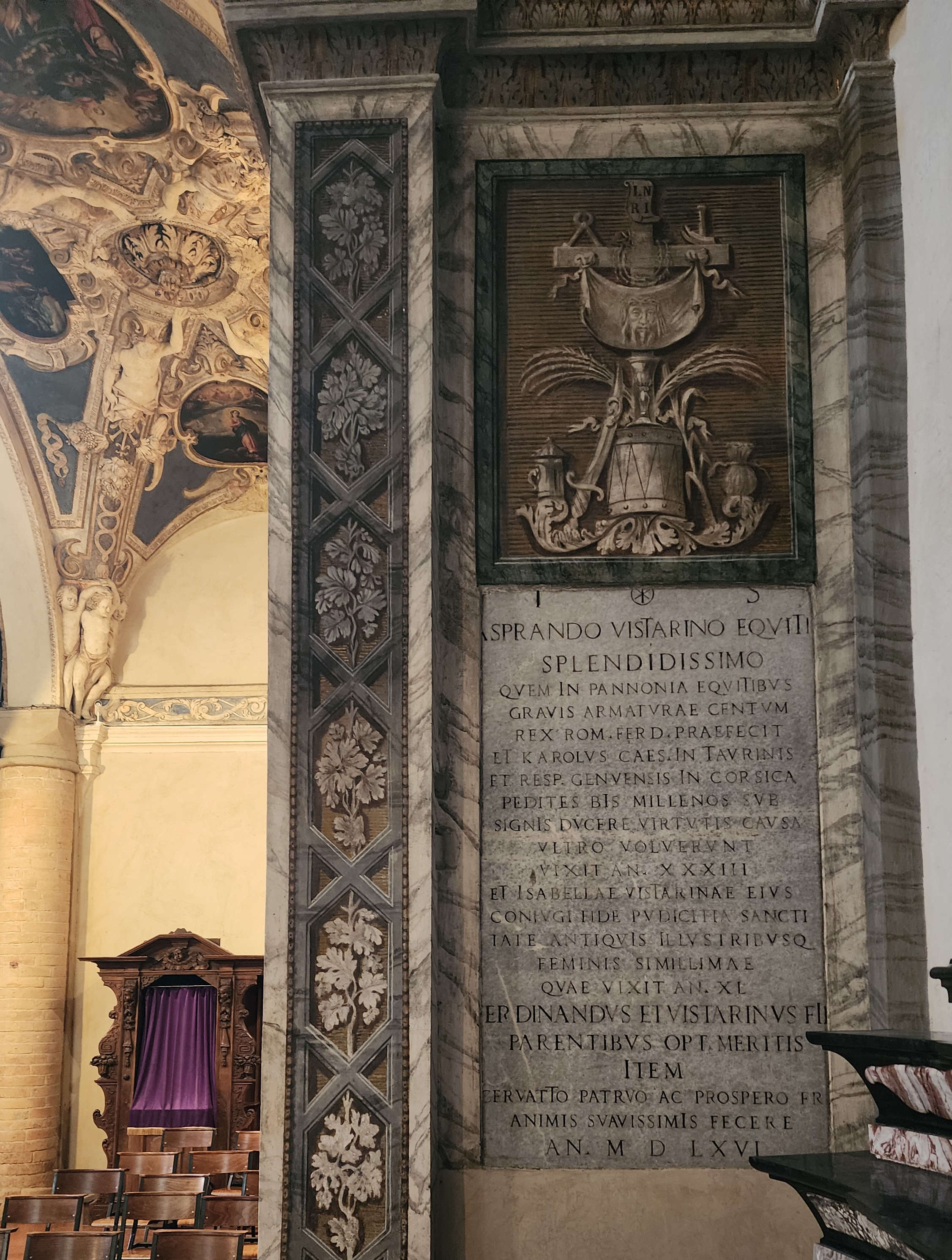

The chapel celebrating the family's exploits is owed to Lodovico's grandson, Ferdinando, also a condottiere like his grandfather. The history of the Vistarini family has been reconstructed in great detail by the studies of Adam Ferrari, who has not neglected to point out the relevance of the dynasty for the fortunes of the arts in Lodi throughout the sixteenth century, since part of what can be admired in the city today is due to their patronage. Ferdinand had fought, and with honor, but the profession of arms did not appeal to him: he preferred art. A "tireless patron," as Ferrari called him, it was he who commissioned the Pietà from Bernardino Campi in 1572, when he was in his thirties, but not only that: he had promoted works in the Cathedral, he saw to it that the church in Zorlesco, the family's home village, was embellished, and he bought the fiefdom of Brembio where he would surely have planted another of his residences if fate had not reserved for him an early death, at only thirty-six. Had his fates been different and granted him a long life, it is likely that he would be remembered today as one of the most munificent supporters of the arts of his time. A common fate, moreover, also shared by his father Asperando Vistarini, who passed away even younger, at the age of thirty-three. In the Vistarini chapel in San Lorenzo one immediately notices the plaque that Ferdinando had affixed in memory of his parent, and which is intriguing not only because that thirty-three in Roman numerals is in the center of the plaque, clearly evident, but also because the plaque condenses a series of feats that are difficult to imagine for such a young man: He fought in Hungary, was knighted by Charles V, and was on the side of the Genoese in the war in Corsica, where he went to fight against the islanders who wanted to become independent from Genoa. That sea campaign was fatal to him, since Asperando fell ill in Corsica and died on the way back: he is buried in San Lorenzo with his wife Isabella. The other plaque instead commemorates his paternal grandfather, Lancillotto Vistarini, also a soldier.

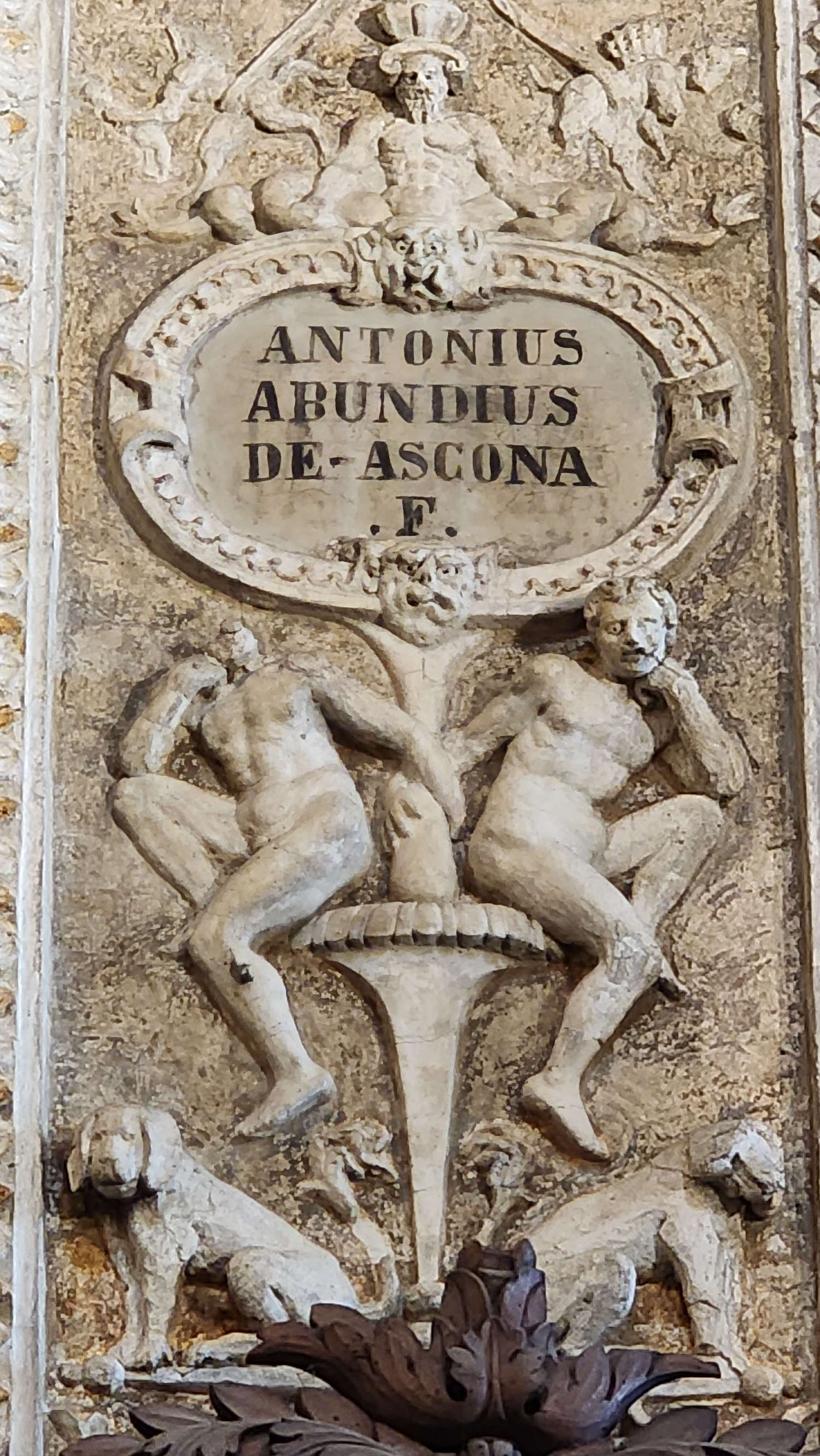

Ferdinando Vistarini had an eye for notable artists. He had not only commissioned the altarpiece from Bernardino Campi, but also entrusted the execution of the noble coat of arms on the vault to one of the outstanding stucco sculptors of the time, that Antonio Abondio of Ascona who today is known only to a few specialists but who must have been among the most highly regarded artists of his time if it is true that Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, in his Rime of 1587, includes him among the most important sculptors active in Milan at the time. Few of Abondio's works remain to us today: the coat of arms is among them, but in the church of San Lorenzo there is an even more significant undertaking of his, which evidently had to convince Vistarini to call on him for the decoration of the family chapel. Years earlier, between 1565 and 1568, Abondio had been entrusted with the realization of the imposing choir, which the artist moreover proudly claimed by affixing his signature, huge, there where everyone could see it: inside a fake painting hanging from one of the two pillars supporting the elaborate entablature beyond which the fresco of the Resurrection that fills the entire apsidal basin opens to the eyes.

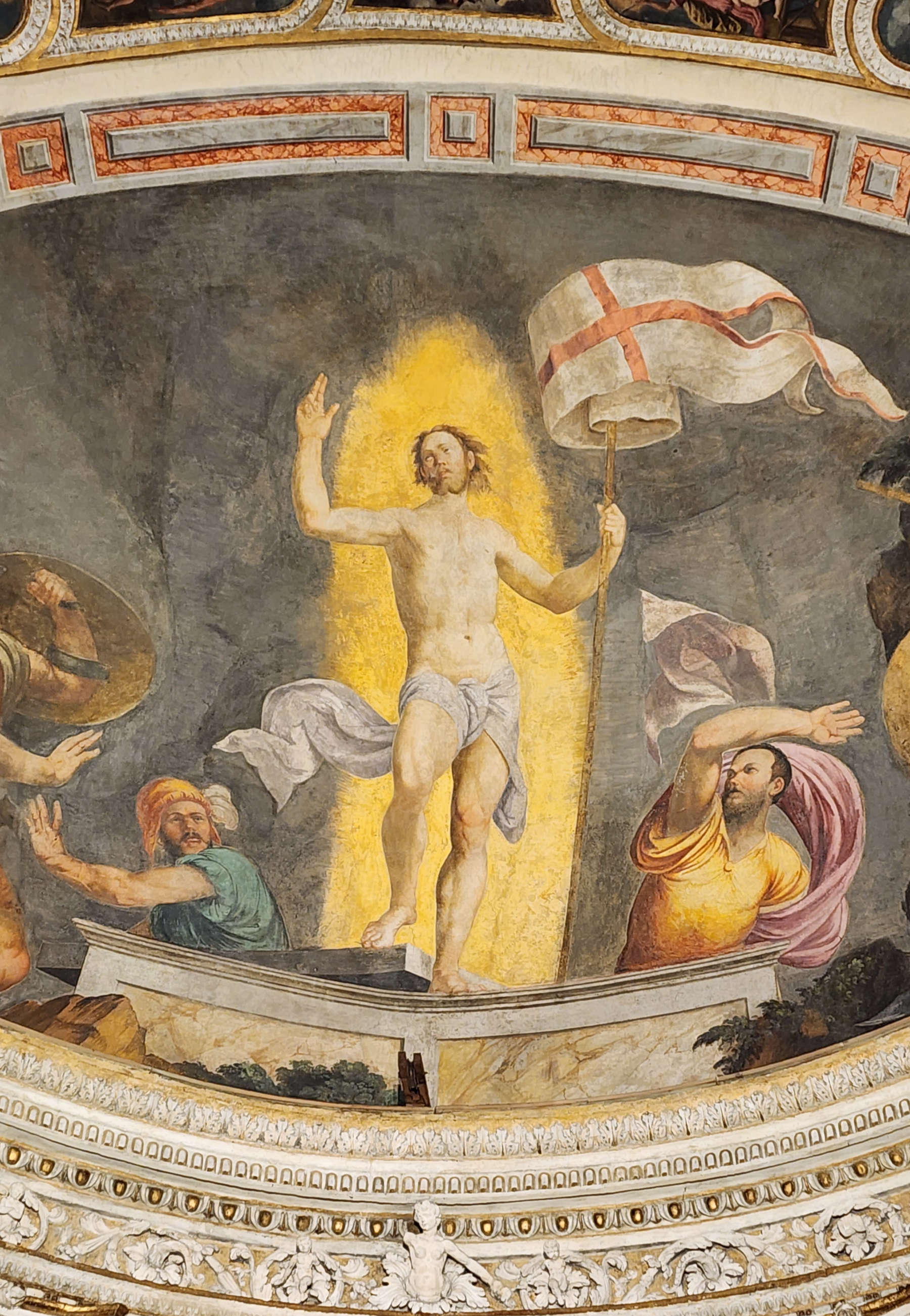

Abondio found himself having to work on the frescoes that had been painted more than twenty years earlier by Callisto Piazza: the Resurrection is the only one that survives, the only, vivid testimony of the greatest Lodi painter of the sixteenth century inside the church of San Lorenzo. A fresco that has also been poorly considered by critics, perhaps because of the extensive eighteenth-century repainting, which became necessary after the apse was struck by lightning in 1732, and which conditioned the opinion of twentieth-century critics. The qualitative deviations, after all, are evident: just look at the sky, which has been almost completely redone. Yet, the figure of Christ, the best-preserved portion, denotes all the powerful, imperious quality of the painting of Callistus Piazza, who, curiously enough, when he was commissioned to paint the frescoes of the apse of San Lorenzo had from the provost Matteo Camola total freedom to choose the subjects, a case of surprising rarity but attesting to the consideration the Piazza brothers must have enjoyed at the time in their city. The only condition was that they would have to match in quality the paintings they had done shortly before in the Temple of the Incoronata, still considered the jewel of Lodi Renaissance art. We will not know if the Piazza brothers succeeded in the undertaking, since only the Resurrection remains: that Christ, so classical, so monumental, so serene, so harmonious, so credible in his illusionistic striding out of the tomb, well rivals, however, the figures of the Incoronata.

We lost, then, the paintings of the Piazza, but we gained one of the best stucco decorations in all of Lombardy. In the same years, we are not sure whether before or after, Abondio had sculpted the great telamons of the Casa degli Omenoni in Milan, his best-known work: Ugo Nebbia, in commenting on these works, wrote that we find ourselves here before "one of the best champions of that pleiad of our sculptors long active in France." However, rather than France, Abondio, even here in Lodi, seems to look to Michelangelo's Rome: the score of his decoration echoes that of the House of the Omenoni, with the large niches escorted by two telamons on each side, and one of them, the one accompanying the statue of Judith, is an almost literal quotation from Moses, complete with hand on his chest adjusting his beard and cloak. The epic gigantism of his figures addresses Rome, and the echo of the Eternal City also resonates in Lodi by innerving with harsh vigor the telamons and the four biblical heroes that Abondio inserted in the niches: St. John the Baptist, caught in contrast and with a stern gaze fixed before him, Judith who raises her armored arm in victory, holds the severed head of Holofernes with her left hand and towers over his abandoned body with crude realism on the lower edge of the niche, and then David who with an almost feral expression is caught at the moment when, with his sword, he is about to pounce on Goliath already lying on the ground, who is protruding out of the niche, and finally the Erythraean Sibyl, the most classical of the four figures, enraptured in ecstasy. Works neglected by all, yellowed, forgotten. Yet powerful ones, perfect counterbalances to the exact geometries and perspective virtuosities of the wooden choir that would shortly thereafter be carved, it was 1578, by Anselmo de' Conti, who in turn intervened by dismantling some of Abondio's stuccoes.

The chain then broke, and the result is what you see: a multi-layered apse. Images that contradict each other, yet it almost seems as if no tension is felt. There is no distance between the violent heroes of Abondio and the compassed saints of Anselmo de' Conti. Between the solemn medieval figures surviving between chapels and the grotesques of two centuries later. Between the shrine where Lodi's richest family celebrated its exploits and the secluded reserve of one of their obscure contemporaries who actually made a profession of humility by dedicating the decorations of her chapel to St. Francis. The fragile soul of a community that no longer exists and still lives among these naves, almost clandestinely.