The Chimera of Arezzo: history of the most important and famous Etruscan bronze

The Chimera of Arezzo, found in 1553, has been recognized as the most important Etruscan bronze ever, and is a work that conveys much information about Etruscan civilization. From discovery to significance, the story of one of the most celebrated works of antiquity.

By Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta | 08/10/2025 12:35

One can only imagine the sense of astonishment that, on that November 15, 1553, the people of Arezzo felt when news spread of the discovery of the splendid Etruscan bronze we know today as the Chimera of Arezzo. And even greater must have been the wonderment of the workers who worked where the bronze was found: an excavation near the walls, near the Porta di San Lorentino, during the construction of a new bulwark wanted by Duke Cosimo I de' Medici. The Chimera was found at a depth of five meters, along with a group of votive bronzes that had been buried there for centuries: animals and human figures all around 20 centimeters in height, while instead the Chimera reaches almost one meter. Somewhat like what happened only a few years ago, in 2022, when the San Casciano bronzes were found, another of the most sensational discoveries ever about Etruscan art. Five centuries apart, but the astonishment when something so unusual and so unexpected is discovered is still the same.

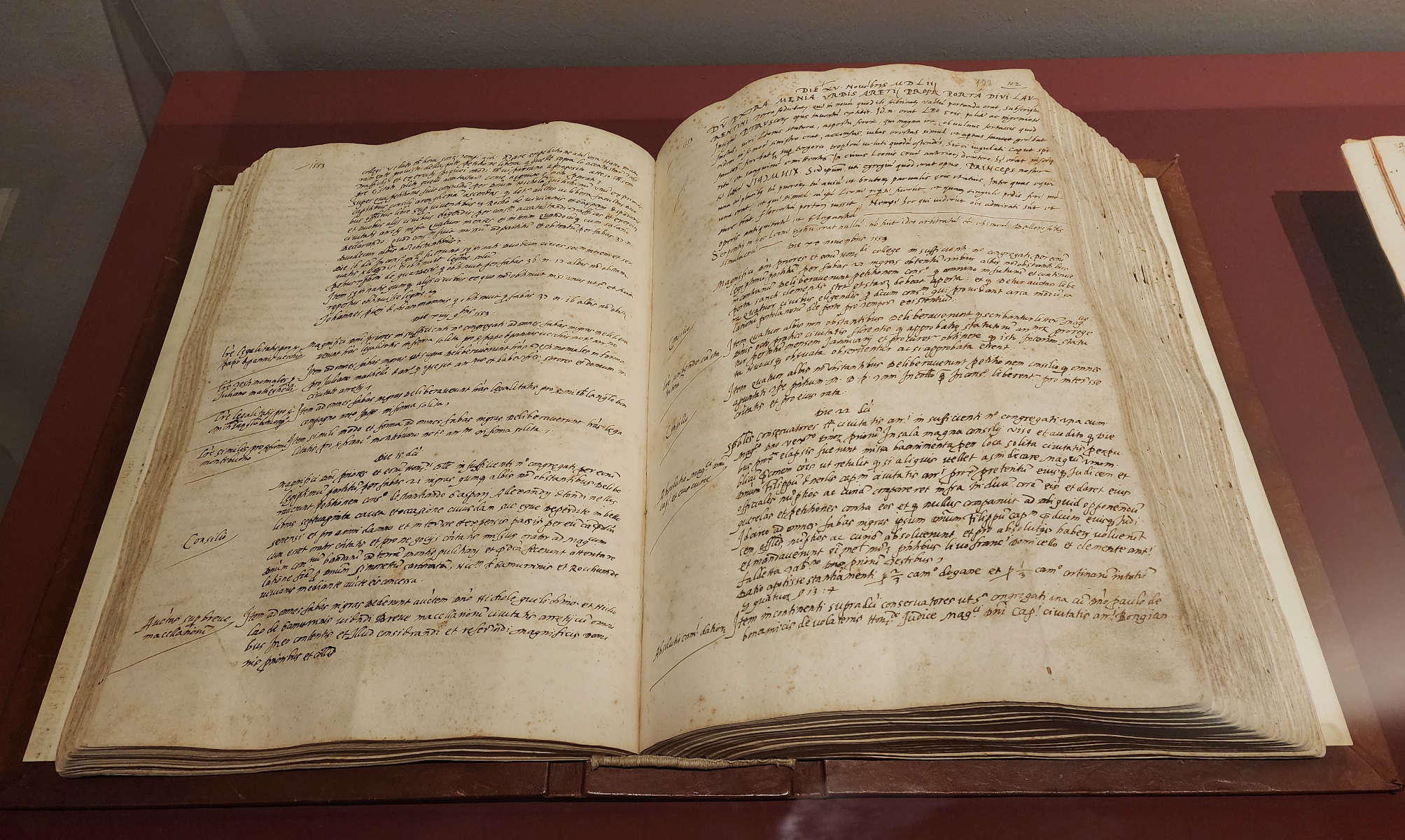

The discovery of the Chimera of Arezzo, which the Etruscologist Vincenzo Bellelli called "by far the most important Etruscan bronze ever," is noted in the Acts and Deliberations of the party of priors and the general council of the Municipality of Arezzo, a kind of register of what was happening in the city at the time. And this very document, written in Latin, not only underscores the exceptional nature of that find, but also the outcry that the discovery caused among the people of Arezzo. The Chimera, recorded in the Acts as "insigne Etruscorum opus," "distinguished work of the Etruscans," was part of a stipe, or votive deposit, and from its origin had a function related to religion, since on the right front leg of the beast is written "TINSCVIL," or "TINS'VIL," meaning "given to the god Tin," the Etruscan correspondent of the Jupiter of the Latins. It was the most significant and largest piece in a series of bronzes that were immediately sent to Florence, to the Palazzo Vecchio, along with the large statue depicting the mythological being, so that it could be seen by the duke (who, of course, wanted to keep the findings in Florence, and this desire of his moreover caused some disappointment in Arezzo) and the whole thing cleaned up. That it was an Etruscan work, therefore, was immediately clear to all, as was clear the value of the work. The subject was not immediately clear, however, because the Chimera appeared without the snake-like tail: it was found only at a later time, and was added to the statue in the eighteenth century with a restoration carried out by the sculptor Francesco Carradori (Pistoia, 1747 - 1824). Initially, the Chimera equivocated for a lion, but was later recognized, after a few months, as the beast of Greek mythology thanks in part to the work of scholars of the time, who measured themselves against classical literature and, above all, ancient coins depicting the Chimera that were decisive in identifying the subject of the sculpture. According to the ancient tale, the Chimera was a monster with the body and head of a lion, a goat's head on its back, and a snake for a tail. She is also described in Homer'sIliad as "the monster of divine origin, / lion's head, goat's breast, and dragon's / tail; and from her mouth hideous flames / spewed forth of fire: and yet, / with the favor of the gods, the hero extinguished her." The poet was alluding to the monster's main 'weapon,' its ability to breathe fire. According to the myth, it had been spawned, like other monstrous creatures such as the Hydra of Lerna, Cerberus and Ortro, from the offspring of Typhon and Echidna, and dwelt in the sheer mountains on the coast of Lycia, a region in present-day southwestern Turkey. The Chimera terrorized the people of Lycia, so King Iobates, tired of these constant incursions, called upon the Greek hero Bellerophon to slay the beast: Poseidon's son succeeded in defeating it with the help of the winged horse Pegasus and a stratagem, namely, by throwing a lead spear into its mouth, which melted with the heat of the flames spewed by the Chimera and killed it by suffocating it.

The bronze found in Arezzo depicts her at the moment of the fight against Bellerophon: moreover, it has been assumed that in ancient times she was part of a large group that also included the statue of the hero (this is the position, moreover, of one of the greatest Etruscologists, Giovannangelo Camporeale), which, however, has not reached us nor does it seem to have left any trace. The Chimera is aggressive, its mouth wide open and bent over on its front legs, caught as it is about to attack the hero. However, it is wounded: in fact, a cut can be seen on its left hind thigh, and the goat's snout also appears turned to one side with its tongue sticking out, as if it is in pain, if it is about to die. Nevertheless, the fair certainly has not lost its will to fight, on the contrary: even the mane, with all the bristling hairs, is a symptom of the fearsome animal's aggressiveness. The snake should have been facing Bellerophon: Carradori, however, chose to position it in the admittedly somewhat senseless act of biting a goat's horn (and we know from ancient coins, however, that that certainly should not have been the correct position). It is a fine work of skilled Etruscan craftsmen, datable, for stylistic reasons, to the early 4th century B.C: if in fact the rather schematic mane and lion's muzzle seem the least innovative elements of the whole, and recall Greek models of the previous century (the work's dependence on the Greek world will be discussed later), the very naturalistic depiction of the body, with the muscles in tension, the skin revealing the rib cage, and the veins in relief, denote instead great modernity. It is precisely this combination of archaizing elements and modern depictions that is a rather peculiar feature of Etruscan sculpture of the first half of the fourth century BCE, and it is therefore a characteristic that leaves little doubt as to its dating.

When the Chimera arrived in Florence, soon after its discovery, it seems that the duke himself had enjoyed cleaning it, under the supervision of Benvenuto Cellini (Florence, 1500 - 1571), who, like Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574), was an eyewitness to what happened in those days of 1553. Cellini himself, in a passage of his autobiography, recounts the finding of the Chimera and also the pleasure Cosimo I took in trying his hand at cleaning the votive sculptures found during work on the walls: "Being in these days found certain antiquities in the contado d'Arezzo, in among which was the Chimera, which is that bronze lion the which is seen in the chambers convicino to the great hall of the [Old] Palace; and together with the said Chimera had been found a quantity of small statuettes, also of bronze, which were covered with earth and rust, and each of them was missing its head or hands or feet, the duke took pleasure in restoring them to himself with certain goldsmith's chisels." When the cleaning work was finished, the Chimera, which was immediately a huge success, was permanently placed in the Palazzo Vecchio, in the Hall of Leo X: the duke, who saw himself as a revived Etruscan prince, had immediately made it a symbol of his duchy. The Chimera, in particular, was seen as a kind of allegory of the enemies Cosimo had defeated by becoming, with the final subjugation of Siena (which just the following year, in 1554, would suffer a crushing defeat during the Battle of Scannagallo, following which Siena itself was subjected to a long siege that ended, in 1555 with its surrender to Florence), the lord of all Tuscany. Vasari, in his Ragionamenti, a treatise describing the works he created at Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, provides a long and detailed description of the Chimera, also relating it to Cosimo I's symbolic ambitions. After explaining the reasons why it was to be considered an Etruscan work (for example, the fact that the hair of the mane was more "awkward," so Vasari says, than the Greeks would have made it: this was for him the main clue), the artist declared that it had seemed good to him to place the Chimera in the Palazzo Vecchio, "not to do this favor to the Aretines, but because as Bellerophon with his virtue tamed that mountain which was full of snakes, chamois and lions, does the compound of this chimera, so Leo X, by his liberality and virtue, won all men; that he ceded then, fate willed that it should be found in the time of Duke Cosimo, who is today tamer of all chimeras." Not everyone, however, read the Chimera in the same way: for example, Annibal Caro, in a letter sent to Alessandro Farnese on May 11, 1554, considered it not exactly a happy work as an allusion to Florence, since the lion, which could recall the Marzocco symbol of Florence, was wounded, and the dying goat could call to mind Cosimo I himself, who had chosen Capricorn as his own personal feat. The work, however, would remain permanently in Florence, publicly displayed in the Palazzo Vecchio where everyone could see it. Among those who marveled at this Etruscan bronze was one of the greatest artists in the history of art, Titian, who, according to the testimony of his friend Pietro Aretino, having seen the "bronze lion," "was astonished as I read how the drops of blood showed themselves in such a tender and liquid manner scattered ne le ferite."

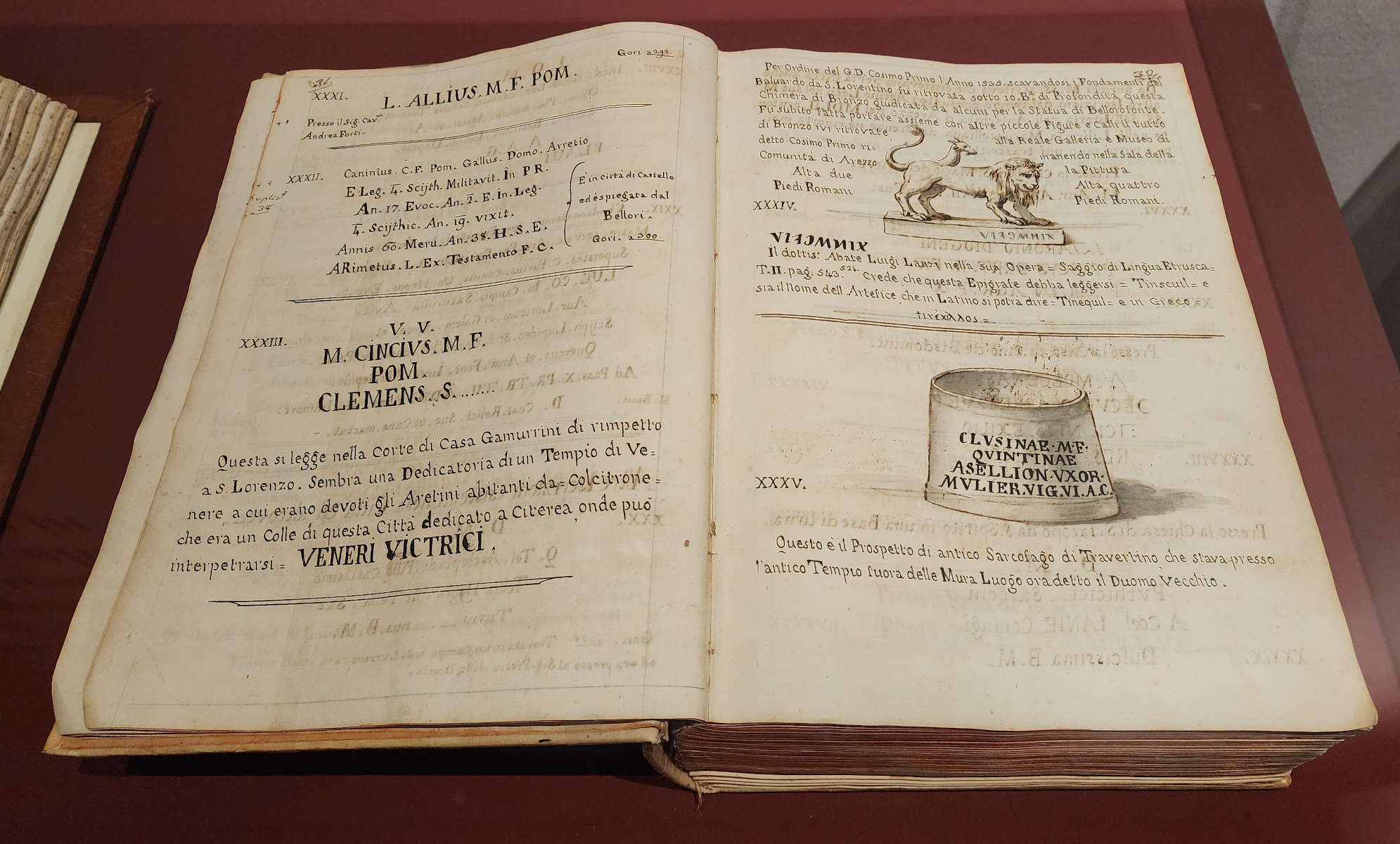

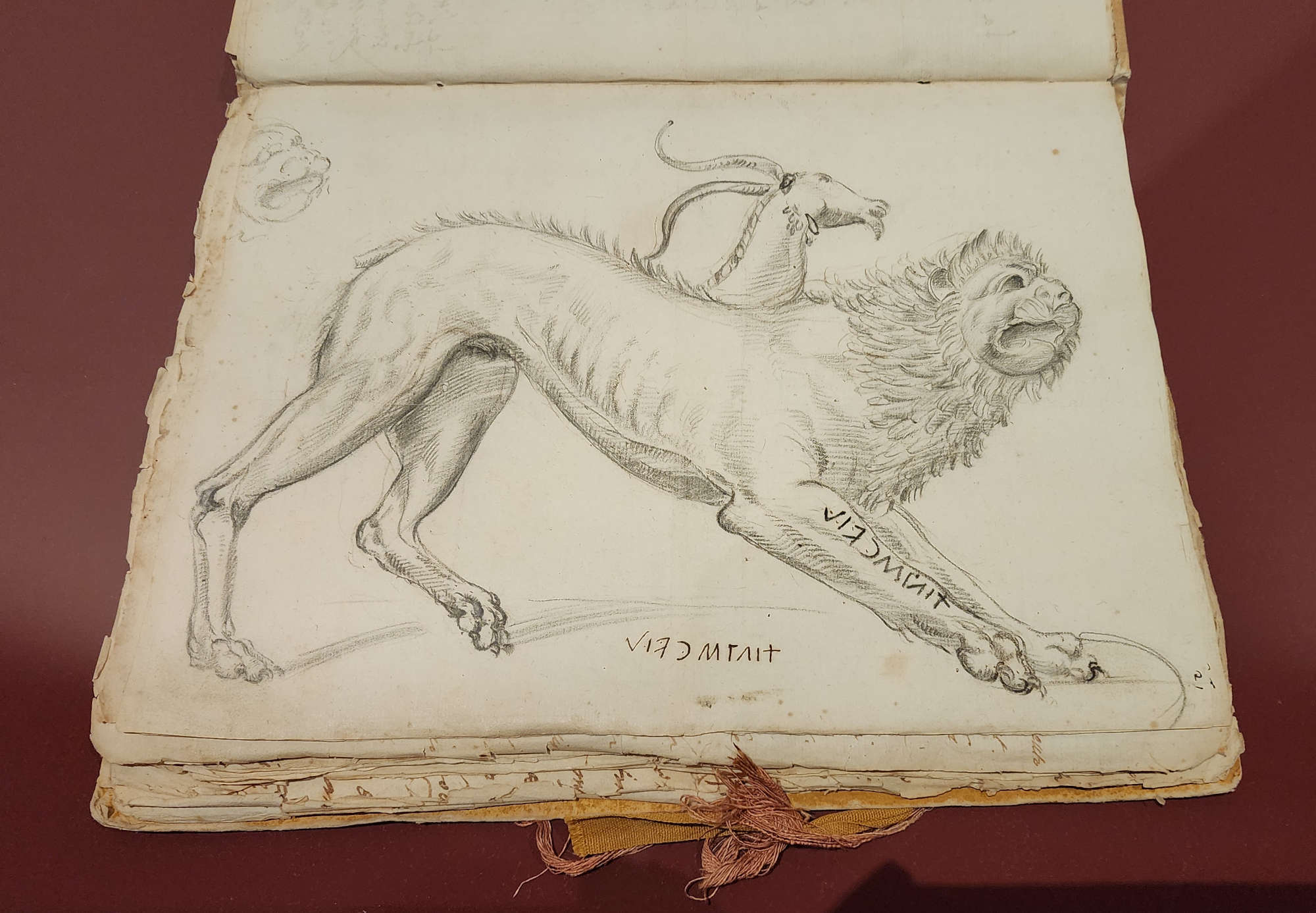

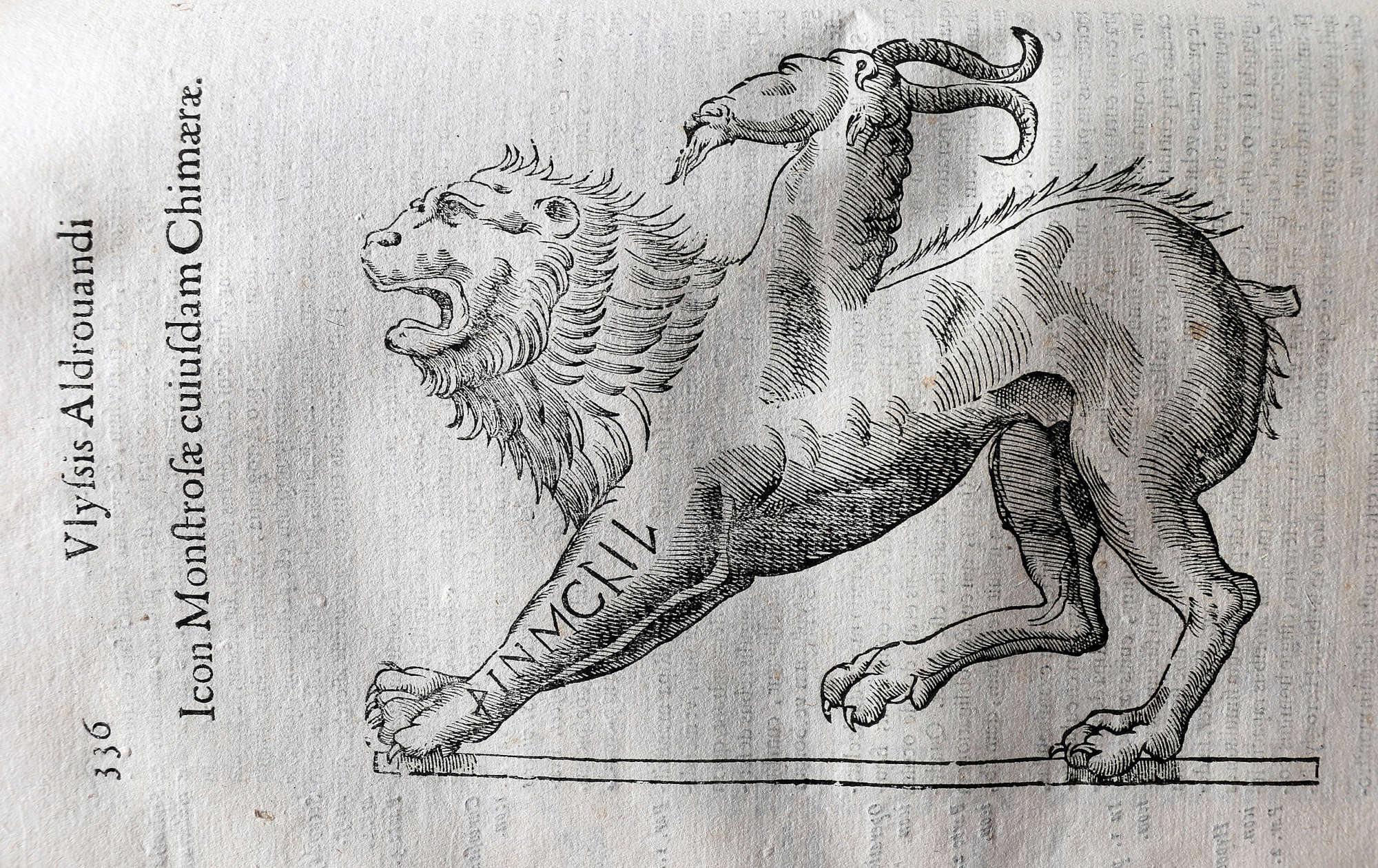

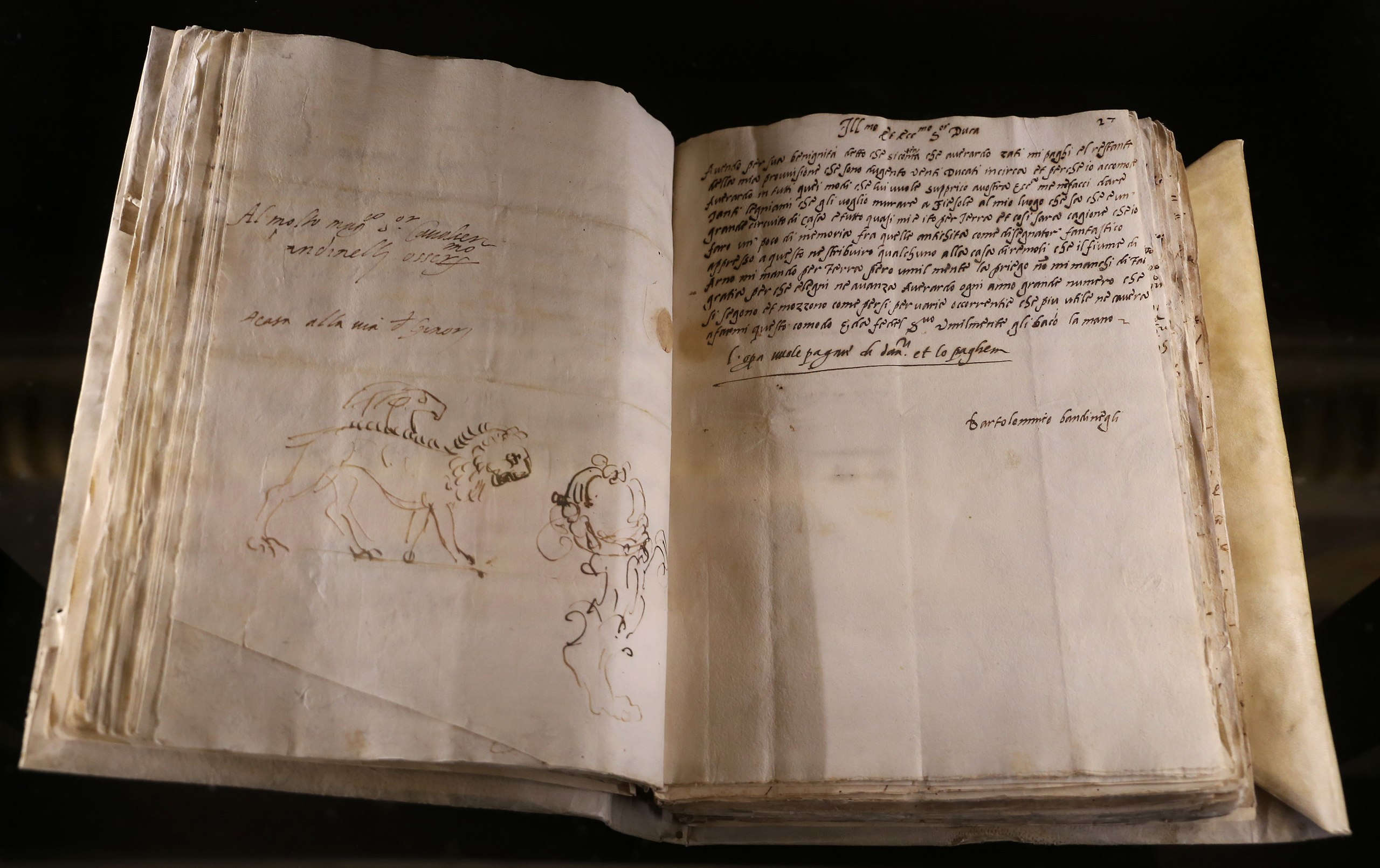

We then know that, to celebrate the discovery, a celebratory painting was executed in Arezzo (we do not know who executed it, however, nor do we know who commissioned it), which was executed immediately after the discovery according to the studies of Maria Gatto, who has been working on this work, and which was placed in the Sala del Comune: a meager consolation for the people of Arezzo who probably hoped to keep the sculpture in the city. The painting, known from the texts of the time as "the Painting," has not survived: however, a drawing dated 1807 by Antonio Albergotti (Arezzo, 1758 - 1841), part of a manuscript preserved in the Arezzo State Archives, has survived, and is thought to depict the Chimera as it was depicted in the painting. Painting that, moreover, was not executed having the real Chimera as a model: for this reason the depiction in Albergotti's drawing appears so dissimilar to the sculpture. However, there are several attestations of the fortune the Chimera enjoyed in the 16th century (the exhibition on Giorgio Vasari organized in 2024 in Arezzo devoted an entire room to this topic): the celebrated naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (Bologna, 1522 - 1605) included it in his Monstrorum historia, a treatise on monstrous and legendary creatures (a sort of medieval bestiary in modern guise, moreover, amazingly, with many of the mythological beasts believed to be real), and then again it can be found, reproduced in a decidedly faithful manner (and without the tail) in a pair of drawings preserved at theState Archives in Perugia and formerly belonging to the Eugubine scholar Gabriele Gabrielli, a great lover of Etruscan history who had drawings of the Chimera sent to him from Florence. The Chimera also appears in a drawing by Baccio Bandinelli (Florence, 1493 - 1560) traced mainly for documentation purposes (it is, moreover, the earliest known drawing depicting the Chimera of Arezzo), and in a sheet by the Spanish Dominican Alfonso Chacón (Baeza, c. 1540 - 1599) depicting the front legs of the mythological animal.

What does the Chimera tell us about Etruscan civilization? As is the case with many works of antiquity, and particularly ofEtruscan art, we do not know who the author of the work is, nor can we know exactly what it was made for. Nevertheless, the work is capable of revealing to us significant aspects of the religion, craftsmanship, and culture of the Etruscans, as well as their relationship with the Greek world (it then seems appropriate to recall that a vigorous and long-running debate about the purpose of this work is still ongoing among scholars, although it is difficult to predict that the various positions will come together). The inscription on the paw is a crucial element in understanding this artifact: indeed, the dedication to the god Tin clarifies the religious function of the work. This element makes us aware of the Etruscan practice of honoring deities with precious gifts, probably to ingratiate oneself into the favor of the gods. The choice of a work of great finesse and very high value such as the Arezzo Chimera for the votive gift to the father of the gods of Etruscan mythology underscores not only the importance of the cult of Tin in Arezzo, but also the value, even material value, that the Etruscans attached to votive offerings. And this, as will be seen in a moment, was perhaps invested with a significance that went even beyond religion.

Again, the Chimera is an extraordinary testimony to the skill achieved by the Etruscans in metallurgy. Moreover, the work was made using the lost-wax technique, of which the Etruscans were important pioneers, but not only: the artisan (or artisans) to whom we owe the Chimera of Arezzo had achieved a very high mastery of this technique, a mastery without which it would not have been possible to render in such detail the anatomical details of the monster (an element that, moreover, reveals a certain knowledge on the part of the artist who handled the work). However, it should not be thought that the Chimera is an isolated work: in fact, it is part of a fruitful dialogue with Greek civilization. Meanwhile, because of the choice of subject, which shows how Etruscan elites integrated Greek narratives and iconography within their own cultural and religious system. And then, the manners of the work itself reveal clear ancestry of Greek models (it is typically Hellenic, for example, the high degree of naturalism), so much so that it has even been speculated that the Chimera may be the work of Greek craftsmen active in Etruria (this, for example, is Piero Orlandini's position), at a time when many artisans who came from Greece were constantly moving around central Italy. "The Chimera," scholar Adriano Maggiani has written, "falls squarely within this Attic current that informs Etruscan-Latian art in the early 4th century BCE": however, according to Maggiani, this does not necessarily mean that the Arezzo Chimera is the work of Greek craftsmen alone. To define this aspect of the question, it is "appropriate to take into consideration also the element of the votive inscription on the right paw [...], drafted with the graphic standards of southern Etruria, even if the lack of characteristic features prevents a definitive judgment. It seems in conclusion more it is prudent to think, for the Chimera, not so much of a single artist personality, but rather of the work of a craft team, within which the model and stylistic form, of Attic matrix, are ensured by Greek (or Italiote) workers, while the skill technical skill necessary to ensure the perfect outcome of such a demanding casting could be provided by Etruscan workers, whose competence in this field was already proverbial; Etruscan must also have been the component that took care of the proper insertion of the work in the relevant context, ensuring, for example, the necessary epigraphic kit." The work, in essence, was made on a Greek model, but it must have required the mastery of Etruscan bronze workers.

It was, moreover, a very expensive work, not least because it had to include, in all likelihood, details in precious materials that have not come down to us (for example, the eyes or the teeth, all details that would have given further expressiveness to the beast). According to Vincenzo Bellelli's hypothesis, the work must initially have had political significance: perhaps it was a donarium, a gift to the deity, of public significance, made to celebrate the military intervention of a Tarquinian condottiere, Aulus Spurinna, who around 400 B.C. was called to Arezzo by the local ruling class to tame a social revolt that threatened the city. The Chimera would thus be the symbol of sedition, and Aulus Spurinna would be celebrated as the new Bellerophon who, called to Arezzo's rescue, succeeded in defeating the rioters and restoring social order. The erection of a donarium centered on the killing of the monster and dedicated to the god Tin, guarantor of cosmic and social order, would thus have symbolized the danger escaped and order restored. Again according to Bellelli, the donarium would then have been destroyed probably as a form of damnatio memoriae towards the patron who had promoted it, perhaps because he had fallen into disgrace. However, we can only move in the realm of hypothesis.

The Chimera remained in the Palazzo Vecchio until 1718, when the work was moved to the Uffizi Gallery, and then in the nineteenth century to the Royal Archaeological Museum of Florence, now the National Archaeological Museum, where everyone can admire this extraordinary artifact. The people of Arezzo, however, have long insisted that the Chimera should return to the city where it was found: the presence of the work at the aforementioned Vasari exhibition has helped fuel the debate about its possible return once again, with several hypotheses under consideration. For the city, in fact, the Chimera is much more than an archaeological find: it is almost the soul of the city, a bridge to its Etruscan origins, a symbol of the community.