Ten objects to learn about the life and culture of the Etruscans

From votive bronzes to funerary urns, from sarcophagi to monumental sculptures, museums in Tuscany and other Italian regions preserve Etruscan masterpieces that tell the story of the life, spirituality, and art of a people who still fascinate.

By Noemi Capoccia | 15/11/2025 21:06

What objects provide insight into the complexity, spirituality, and sophistication of the Etruscan people? In short: is it possible to compile a list of ten objects for understanding the Etruscans? We have tried. Cinerary urns and votive bronzes that tell the story of daily life, funerary rituals and the journey to the afterlife, or masterpieces of sculpture of extraordinary workmanship that show the fusion of Etruscan tradition and Greek and Roman influences, and even works of jewelry, votive chandeliers and tools for everyday life. But that's not all: there are also objects with symbolic and ritual functions, or even artifacts that tell the story of the family life of this people, revealing beliefs, social hierarchies and ritual practices, highlighting the elegance, attention to detail and technical innovation of Etruscan craftsmen. To visit museums that preserve Etruscan artifacts is to come into direct contact with a civilization that knew how to combine aesthetics, symbolism and daily life in works that can still speak today. Here are the works that can tell us more about this people than others.

1. The Afterlife: Etruscan funerary urn with a scene of a journey into the Underworld (Volterra, Guarnacci Museum)

The Guarnacci Museum in Volterra, among the oldest public museums in Europe, holds one of the most extensive collections of Hellenistic cinerary urns in Etruria, demonstrations of the refined aristocracy of Velathri, or Etruscan Volterra. Many finds depict scenes of funerary leave-taking and the journey to the afterlife, typically Etruscan themes showing the greeting between the living and the deceased and the journey into the afterlife, made on foot, on horseback or in chariots. Some urns illustrate the carpentum, the two-wheeled chariot intended for noble women, while others depict the deceased accompanied by relatives, servants or demonic figures such as "Charun," a monster with a deformed face and armed with a heavy hammer. The bas-reliefs and faces of the deceased restore the elegance and charm of the Etruscan world, recounting affections, daily life and beliefs about the afterlife. The Guarnacci Museum's collection, organized since 1877 according to the subjects carved on the lids and chests, provides insight into funerary customs and the symbolic role of rituals in Etruscan culture.

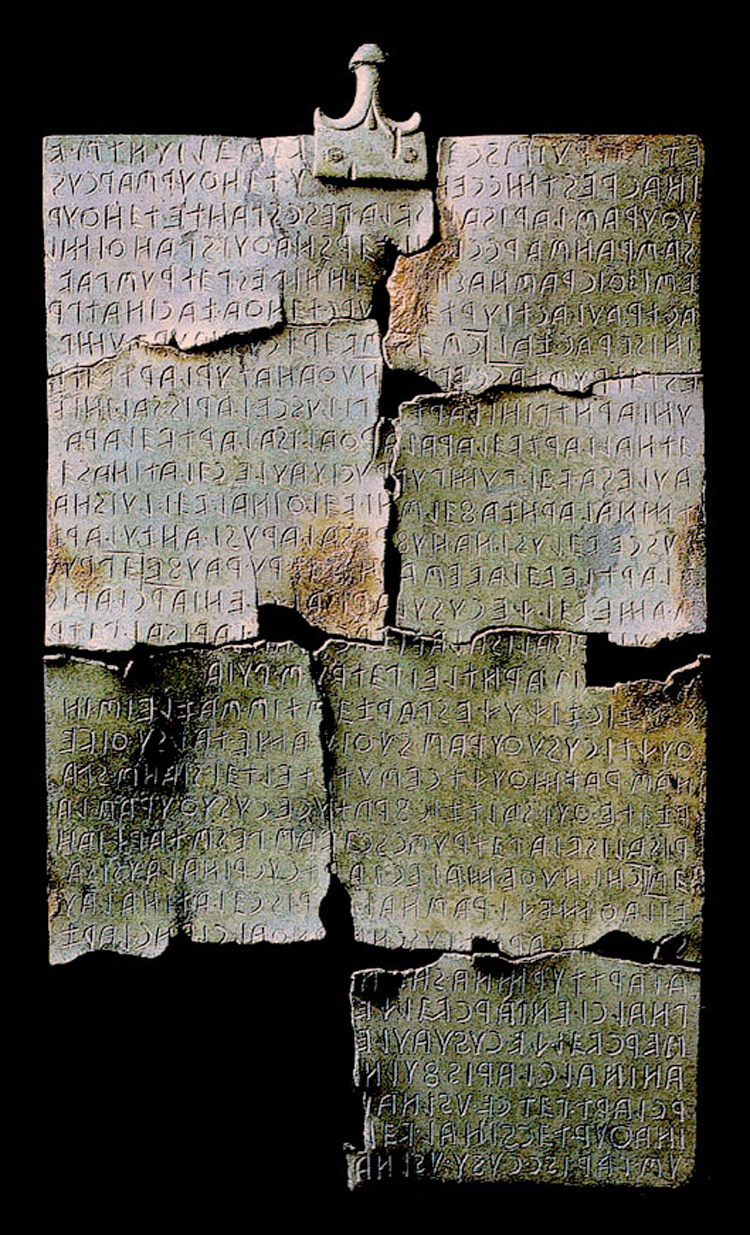

2. Writing: the Tabula Cortonensis (Cortona, Museum of the Etruscan Academy and the City of Cortona - MAEC)

The Tabula Cortonensis, discovered in Camucia, a hamlet of Cortona (Arezzo), and now kept at the MAEC - Museum of the Etruscan Academy of Cortona, contains about two hundred words spread over thirty-two lines on the front and eight on the back. Interesting for its content and the Etruscan style of writing, it shows how the Etruscans did not separate words with spaces, but rather joined them all together, dividing the text by means of dots placed halfway up the letters. The prevailing interpretation regards it as a notarial deed for the purchase and sale of property, dating from the second century B.C., issued by the "zilath mechí rasnai," a chief magistrate similar to the Roman praetor. The tablet, which has come down to seven of its eight fragments, records three members of the Cusu family, Velche, Laris and Lariza, as buyers, and a wealthy oil merchant of humble origins, Petru Scevas, as seller. The purchase and sale took place through the rite (also common among the Romans) ofin iure cessio, a mock trial in which the seller implicitly renounced ownership.

3. The craftsmanship of Etruscan artisans: the Chimera of Arezzo (Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale)

The Chimera of Arezzo represents one of the best-known masterpieces of Etruscan art (albeit, here, much influenced by Greek art: here's an in-depth look at this seminal work), attributable to the first decades of the 4th century B.C. and now welcoming visitors to the National Archaeological Museum in Florence. Its discovery in 1553, recorded in the Acts and Deliberations of the party of the priors and the general council of the Municipality of Arezzo with the definition "insigne Etruscorum opus" ("distinguished work of the Etruscans"), immediately revealed an artifact of a votive nature: the inscription "TINSCVIL" in fact appears on the right front paw, a dedication to the god Tin, the Etruscan equivalent of Jupiter. Identification of the creature took time, as the serpentiform tail was later recovered and integrated in the eighteenth century by sculptor Francesco Carradori. Comparison with classical sources and some coins finally made it possible to recognize the monster mentioned by Homer, consisting of lion, goat and snake. The vigorous anatomy, defined by taut muscles and outcropping veins, combines with a lion's head of a more archaic character and gives the Chimera the profile of a refined work, the result of craftsmen of extraordinary skill.

4. Objects of ritual use: the Etruscan Chandelier (Cortona - Museo dell'Accademia Etrusca e della Città di Cortona - MAEC)

Accidentally discovered in 1840 in the Cortonese countryside, the Etruscan Chandelier of Cortona quickly became part of the academic collection of Cortona, where it remains to this day one of the most important pieces. Coming from a shrine of considerable importance, it was made around the mid-4th century B.C. in workshops in inland Etruria, probably from Orvieto. The base has figurative decoration and phytomorphic motifs, with a gorgoneion in the center characterized by bipartite curls on the forehead and an open mouth with a hanging tongue, surrounded by small hand-carved intertwined snakes. Along the edges are alternating reliefs of Acheloo faces and sixteen spouts, intended for burning lamp oil by means of wicks. A plaque, added later but found with the artifact, indicates the consecration or rededication of the chandelier, offering evidence of the use of reuse in ancient civilizations. The Cortona chandelier probably served ritual purposes and is a key object in understanding the sophistication of objects that were used for cultic purposes.

5. Religious-spiritual aesthetics: theEvening Shadow (Volterra, Museo EtruscoGuarnacci)

The Guarnacci Etruscan Museum in Volterra holds an extraordinary heritage of votive bronzes and objects of daily life, and offers a unique insight into Etruscan civilization. Among the best-known works is the Evening Shadow, a slender, enigmatic male figure that has almost become a symbol of the city. The museum's collections, and the Evening Shadow itself, tell of the spirituality of a people who conceived of the afterlife as a continuation of earthly life, accompanying the deceased with rituals and objects designed to sustain them. The famous bronze statuette, about 50 cm tall, is distinguished by its extremely elongated and slender shape; according to tradition, it was named after Gabriele D'Annunzio, who recognized in it the long shadows that lengthen at sunset.

6. Goldwork: the gold fibula (Cortona - Museum of the Etruscan Academy and the City of Cortona - MAEC)

The gold fibula preserved at the MAEC - Museum of the Etruscan Academy and the City of Cortona, which can be dated to the second quarter of the sixth century B.C., represents an extraordinary example of Etruscan goldsmithing, an art in which this people reached a marked refinement and great maturity. The bow is modeled as a crouching panther, rendered with great plasticity, while the rectangular, elongated stirrup integrates spring and barb in simple gold wire, ending with the protome (the front part of the animal's body, i.e., head and neck) of the panther. The lower edge is finished with a knurled wire articulated in two wheels, and the upper part of the bracket shows, in granulation, the so-called Tree of Life. Found in the grave goods of Tomb 1 of Tumulus II of the Sodo, the fibula testifies to the skill of Etruscan craftsmen and their ability to combine functionality and refined decoration.

7. Funerary sculpture: the Etruscan Sphinx (Chiusi, Museo Nazionale Etrusco)

The National Etruscan Museum in Chiusi (Siena) was founded in 1871, shortly after the unification of Italy, to house the many artifacts returned from the Chiusi area, which had long been plundered. Among the most notable objects in the collection is the large Sphinx, datable to the 6th century B.C., made of fetid stone, so called because of its characteristic sulfur odor. Discovered in the 19th century, the statue, which also testifies to the fusion of Etruscan and Greek culture, was donated to the museum by Count Ottieri della Ciaja. It depicts a being half lion and half human, destined to accompany the deceased into the afterlife. Today it is considered one of the symbols of the museum and is an outstanding example of the funerary and symbolic function of some of the Etruscan sculpture.

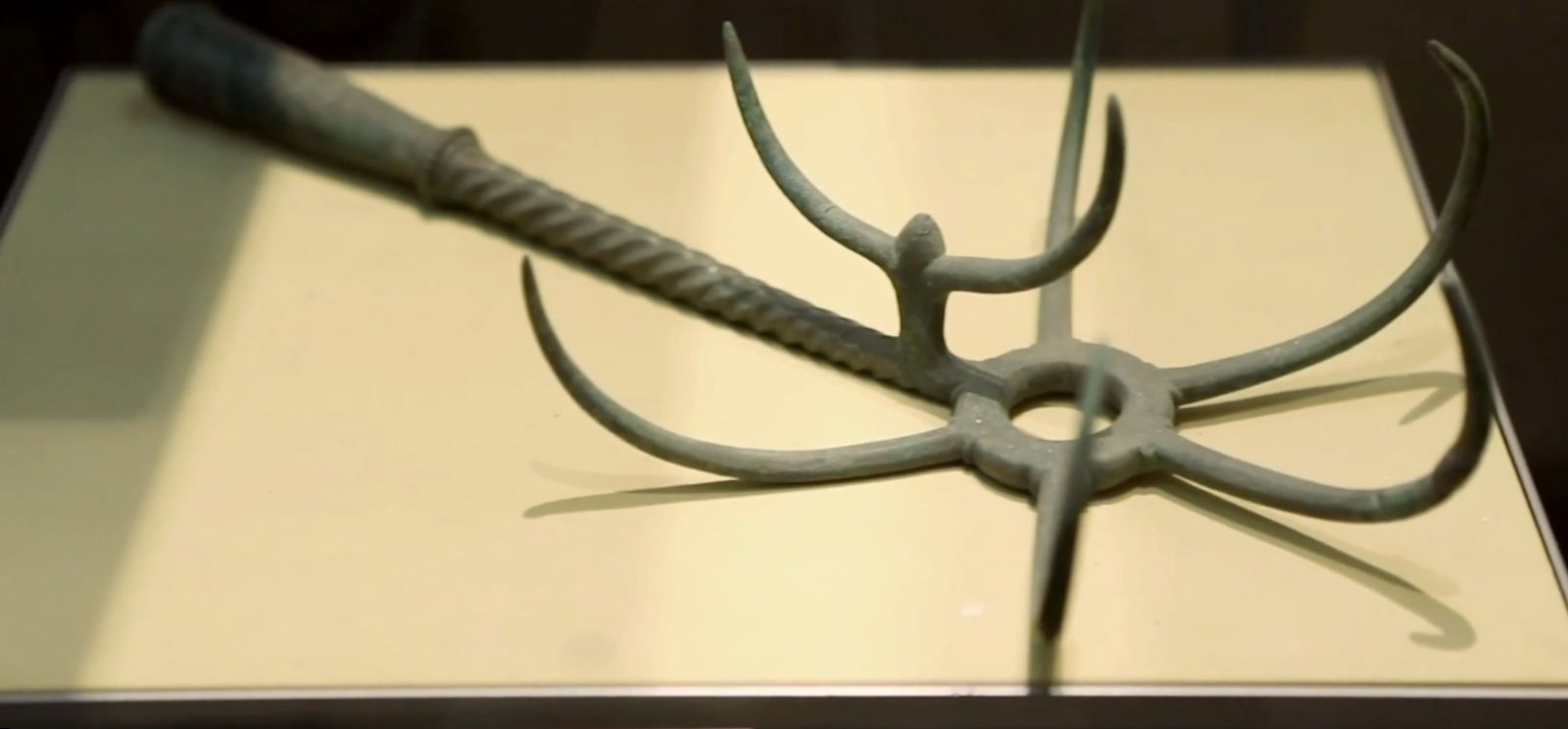

8. Daily life: the graffione (Cortona, Museum of the Etruscan Academy and the City of Cortona - MAEC)

In the 7th century, Etruscan princes discovered that there were more refined ways of preparing and consuming meat in the East. Prominent among the tools they adopted was the graffione, the ancestor of the barbecue and raclette, with which they harpooned meat and plunged it into boiling water until it was cooked to the desired doneness. The use of the graffione not only has a practical function, namely cooking fine meats, but also often becomes a sign of prestige and power, a way of asserting one's importance in front of others. The graffione thus testifies not only to Etruscan gastronomic techniques, but also to the social dynamics associated with banqueting. The work is preserved at the MAEC in Cortona, where it documents the skill and refined taste of a people who knew how to transform cooking into a gesture of distinction.

9. The relationship between man and woman: the Sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom (Rome, Villa Giulia)

At the National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia in Rome is the famous Sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom, the museum's emblem and key to interpreting the relationship between man and woman in Etruscan culture. Its history is linked to Felice Barnabei, the institution's founder, who bought for 4,000 liras the terracotta fragments later reassembled into a masterpiece some 2,500 years old. The work, made from more than four hundred pieces, constitutes an urn intended for the remains of the deceased. The carved couple appears lying on a bed(kline) with their torso erect, in a typical banquet attitude. The man wraps his right arm around the woman's shoulders, and the two faces, characterized by the archaic smile, brush against each other. Instead, the position of the hands alludes to objects that have disappeared today, perhaps a cup or a small vase. The banquet theme, borrowed from the Greek world as a sign of prestige, also emerges in the Etruscan funerary context. Compared to the Greek tradition, the presence of the woman next to her partner in an equal role is innovative, a figure who, with elegance and confidence, seems to dominate the scene: in fact, women in the Etruscan world enjoyed a freedom and independence that were unknown to other neighboring civilizations, such as the Greek or Roman(here an in-depth study on the Etruscan woman).

10. The fusion of Etruscan and Roman culture: The Arringer (Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale)

TheArringatore is a life-size statue depicting a man in a toga, so called because of the typical oratorical pose, and represents the only large sculpture that has come down to us from the last phase of Etruscan art, datable between the late 2nd and early 1st centuries BC, a time when Etruscan culture was already feeling the influence of Roman culture. The bronze is kept at the Archaeological Museum in Florence and was found around 1573 in Sanguineto, near Lake Trasimeno. The figure shows a virile figure standing, wrapped in a pallium and toga, typical garments of Roman culture, wearing high shoes, in the composed and dignified gesture of a raised right arm, typical of public rhetoric. A dedicatory inscription on the flap of the toga allows him to be identified with the Etruscan notable Aulus Metellus , who had nevertheless obtained Roman citizenship (the Etruscan elite, in fact, did not disappear entirely after Rome extended its influence over Etruria). According to archaeologist Pericles Ducati, the work dates from a now Romanized Etruria after 100 BCE; academic Olof Vessberg also recognizes in it influences of the Hellenistic realism that characterized portraiture of the mid-2nd century BCE and is common to both Etruscan and Roman art of the period. The length of the toga and the style of the head, with short, clean-cut hair, hark back to the male figure in the sarcophagus of Aphuna in Palermo, dated between 150 and 100 BCE.