"The ancients always copy us". The Etruscans in contemporary art

Etruscan art, marginalized by the Winckelmannian canon, reveals an expressive tension that spans the centuries and resurfaces in modern and contemporary sculpture: from Giacometti to Marini, Basaldella to Paladino and Gormley, a continuous line of compact forms, vertical presences and restrained tension.

By Francesca Anita Gigli | 10/12/2025 17:21

When, in the eighteenth century, Johann Joachim Winckelmann tries to give a comprehensive shape to the history of ancient art, his gaze constructs a map in which Greece occupies the incandescent center. In the pages of Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums, the History of Art in Antiquity, Greek sculpture is organized as the culmination of an evolution through Egypt and the Italic world, until it reaches that "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" that becomes the measure of all subsequent judgment. In that definition is thickened the idea of a beauty that proceeds by measure, balance, and formal purity, capable of traversing even the violence of the passions while keeping intact the dignity of the body represented. Greek art is the manifestation of a unique condition, a balance between climate, political freedom and culture that the German art historian elects as the supreme measure of beauty.

But within this cohesive design there is a parenthesis concerningEtruria. Between 1758 and 1759 Winckelmann stayed in Florence, studied the Medici collections, urns, bronzes, and engraved gems in the Stosch collection, compiled a catalog of carved stones, and painstakingly recorded inscriptions, iconographic details, and problems of attribution. From that Florentine room, whereEtruscan art is compressed into a few artifacts chosen on the basis of the language of the inscriptions, an image takes shape that will always accompany him: an art that moves on an ambiguous ridge, close in some ways to Egyptizing archaism, in others to the narrative in images of Greece, capable of absorbing Hellenic stories and forms and returning them under a different temperature. The scholar tries to bend it to the evolutionary model he has in mind, a parabola model, with a harsh initial phase, a full maturity, and a final season of imitators. And it is precisely here that the Etruscan form begins to crack the order, not through a theory, but through the force of certain works that never quite run out.

TheApollo of Veio, now preserved at Villa Giulia, is an exemplary representation of the civilization's formal intelligence. The figure seems to advance propelled by a tension that arises from within. The torso is constructed by clear planes, the leg giving the step an irrevocable direction and the shoulders shaped like living volumes. A presence that carries with it the weight of the earth from which it came and continues to expand in space like an organism determined to hold itself up through its own energy. In the Sarcophagus of the Bride and Groom, form becomes relational structure. The couple does not appear as a pair of side-by-side figures, but as a single entity that concentrates in the gesture of the banquet a vision of the world: the elongated eyes that welcome, the firm lips that guard, the hands that touch objects now lost but still present in the memory of the body. The canopic canopies (those faces placed to seal the funerary material) show another way of thinking about the human face. The circular eyes, the tight line of the jaw, the perpendicularity of the nose that holds the entire volume compose a physiognomic repertoire that seeks a firm, recognizable presence, capable of asserting itself while remaining essential. The paintings of the Leopards' Tomb, with the banquet and the players advancing according to a rhythm rather than a rule, construct a space in which color defines the scene with a vitality that still surprises today. From this whole set of works emerges with extreme clarity a principle that overturns the old view. Etruria, between Tuscany, Latium and Umbria, is a laboratory in which form is built through constant density, pressure and accumulation.

It is in this gap that the Etruscan question becomes really interesting for modernity: in the inability of the Winckelmannian model to fully contain an art that, while acknowledged as indebted to Greece, retains its own expressive force, a "more" made of melancholy, cruelty, superstition, and the density of ritual, which pushes out of the smooth path of classicism. Etruria ceases to be just a stage between Egypt and Greece and reveals itself as an autonomous laboratory of forms, a mental and material landscape that, centuries later, will offer twentieth-century artists and contemporary authors a repertoire of compact bodies, concentrated faces and restrained gestures, capable of speaking to a different idea of modernity.

Within this constellation of resurfaced forms, where Etruscan art recovers its own gravity, Alberto Giacometti 's sculpture appears to be traversed by a consonance and firmness such as to return the pace of deep intuitions, those that work underground, in silence, in the very fiber of matter. It is a bond that eludes genealogies and proceeds through tensions, as if certain figures had taught him to recognize that point where the presence of a body depends only on its unique and rare way of inhabiting space. In his wanderings through the halls of the Louvre, in the years leading up to the war and then again in the postwar period, when the museum became a kind of testing ground for the gaze, Giacometti repeatedly came across the Etruscan votive bronzes from Chiusi, Perugia, Vulci, figures only a few centimeters tall that have the compactness of an oath. Those bodies that are fascinating because they are reduced to the bare minimum: a vertical axis, arms adhered to the torso, a head contracted into a few planes, proportions stretched to the point of excess, open in the sculptor's gaze a fissure that lies much deeper than in the official genealogies of modernity; they bring him closer to an ancient way of conceiving the figure, in which existence coincides with the very fact of standing upright.

The standing male figures, with the torso clamped into a single volume, the legs welded into a single descent, and the column of the body advancing without apparent outward balance, condense this vision with a limpid hardness. The sculpture offers no gesture to dilute the weight of the body, no pacifying elegance; it concentrates identity on a posture that seems destined to last as long as the metal lasts, and that is precisely why it strikes the eye. In this choice of economy, in this refusal to dissipate energy in superfluous details, Giacometti recognizes a formal and conceptual discipline that touches his work at the vulnerable point where the figure ceases to be a volume to be modeled and becomes a decision, an act concerning how a body agrees to occupy space.

When, in 1947, he worked onHomme qui marche, this discipline absorbed in the silence of museum rooms emerges in the sculpture with a distinct flare. Man's stride here arises from a collected urgency, in which advancing means guaranteeing the figure's hold, shifting an already precarious balance forward, prolonging for an instant longer the possibility of being in the world. The surface, flayed and compressed, preserves the memory of the work of the fingers, of the continuous distance and proximity between sculptor and material; it does not try to erase the process, it holds it in the bronze as a necessary trace. In the Femmes de Venise this logic is amplified even more: bodies that seem to emerge from an accumulation of layers, stripped of any promise of completeness, reduced to a presence that holds on to a minimal point of contact with the ground and yet, surprisingly, does not give way, never allows itself to be overthrown.

The Etruscan votive heads that Giacometti had approached in his formative years, with their circular eyes, protruding foreheads, compressed jaws, and taut noses that cross the face vertically and become its axis, work on the same idea of strenuous and fierce reduction. Idea that the portrait does not serve to recognize someone, but to fix in matter a form of existence, the obsessive resistance of an individual to the wear and tear of time and ritual. The heads that the Swiss artist models between the 1940s and 1950s are born in this same zone of friction; physiognomy contracts, resemblance recedes, the eyes become hollows in which the pressure of an unfinished life that finds no peace is gathered.

The small figures that Giacometti models in series, then consumes and thins them to the limit of disappearance, repeat at another level the lesson of the Etruscan bronzes. The figure is born large and is reduced little by little, becomes charged with tension as the material diminishes; each subtraction becomes an act of trust in the possibility that the body will endure even in that impoverished, constricted, constrained, almost bony form. The surface registers not solely and trivially the gesture but its arrest, the moment when the hand decides to stop, to entrust the little to speak for the whole. In this stern interplay between erosion and permanence we recognize a reflection that is as much about the history of art as it is about the human condition of the very short century that was the twentieth century.

Votive statuettes, intended for ritual and offering, possess a gravity that does not need monumental dimensions, because it is based on the consistency with which they hold up their task: to stand, to bear witness, to keep open a relationship between the body and the invisible. Giacometti's figures stand at the same point of friction, at that margin where the body has already been consumed and yet stubbornly refuses to fall, to dissolve altogether. They do not seek consolation, they do not seek beauty; they seek a way to last. And in this lasting that has the physical quality of a wound held together, the Etruscan legacy ceases to be a chapter in ancient history and becomes a voice that continues to work in our idea of the figure, just below the threshold of words.

Within this path that links Etruria to the twentieth century, the figure of Arturo Martini also stands out with a force that maintains the exact pace of necessary things, those that do not seek place but take it gracefully. The episode evoked by Dario Fo, that convinced, ironic and almost wounded exclamation "the ancients always copy us," opens a gap in the common imagination. It is the recognition of a continuity that eludes chronologies and runs through artists like a thrill of belonging.

Martini belongs to that genealogy that recognizes in Etruria a repertoire of unfinished solutions, a method of approaching the world through form, and his teaching radiates directly to Marini, Leoncillo, all the way to Italian sculpture of the 1950s.

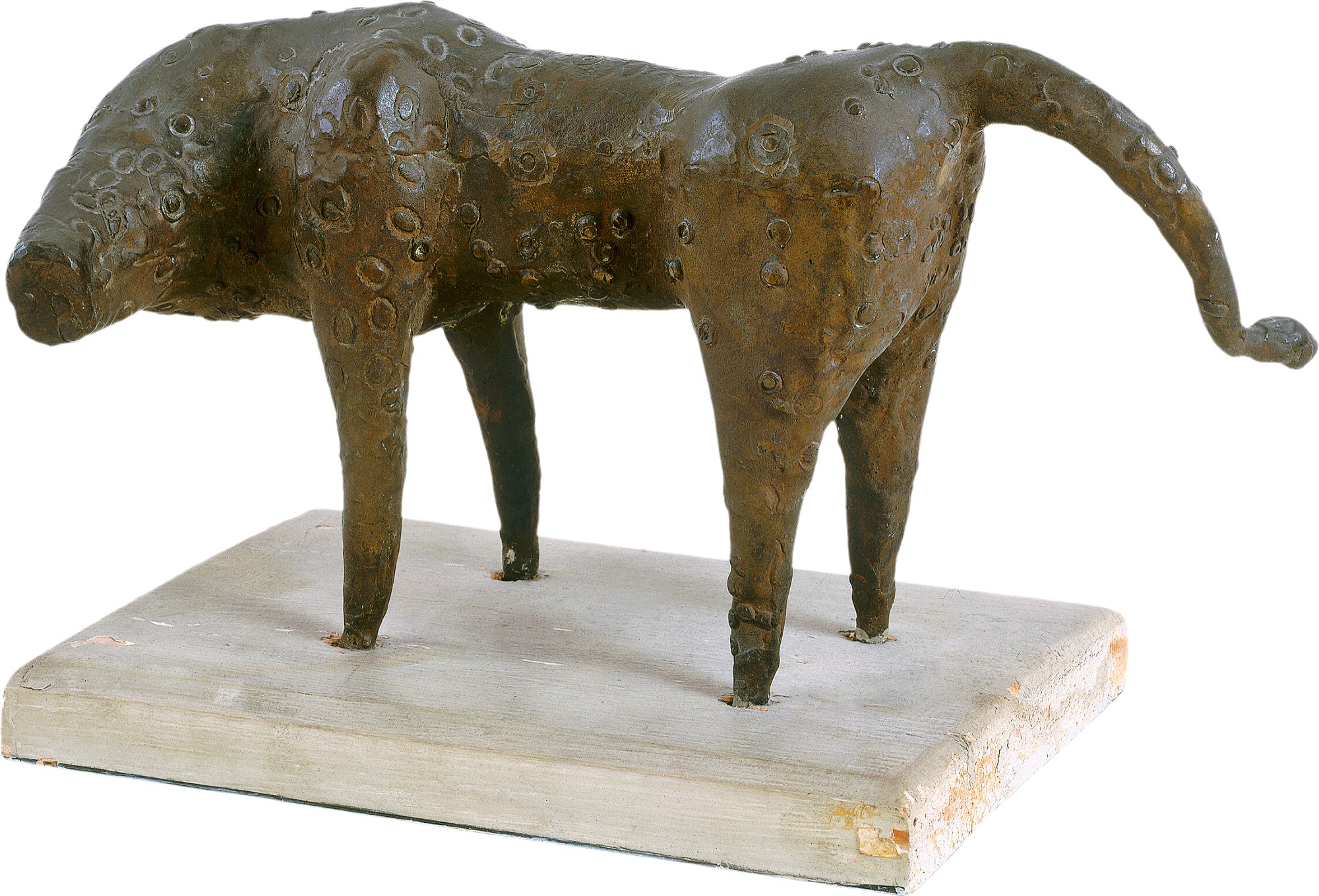

On a parallel axis, sharper and at the same time more collected, Marino Marini enters Etruria as one enters a room you already know very well, a room without superfluous ornamentation. The archaic horses of Volterra, Chiusi, and Arezzo speak to him through their severity; they are triangular heads that cleave space, necks that guard restlessness like a secret between the artist and the material.

Marini senses in those figures a discipline that coincides with his way of thinking about sculpture. Thus are born such works as Cavaliere, Piccolo Cavaliere, Miracolo. Unique organisms composed of man and horse, a compact creature that affirms nothing but a firm cohabitation, a will to hold that belongs more to the material than to the scene.

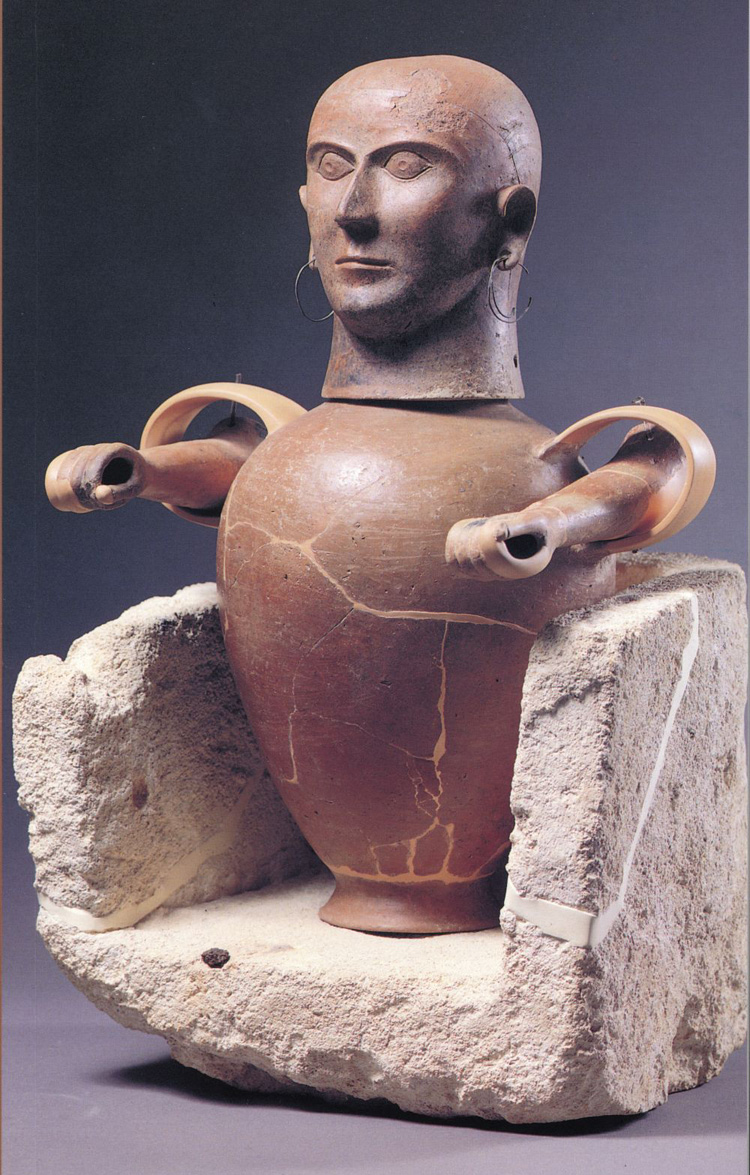

Further from this muscular tension and yet within the same light, Massimo Campigli composes a universe of female figures that seem to come from an inner sanctuary, a place where frontality is charged with authority and the face becomes architecture. His bodies, constructed according to a sharp geometry that does not allow dispersion, are reminiscent of manhole canopic jars and votive terracottas. Her women inhabit a time that cannot be measured, a time that advances by slow stratifications, a space in which the figure resists disorder through the composure of its own axis.

But again, with Mirko Basaldella, the material tangles and ignites. He plunges his hands into bronze as if working the scorched earth of a necropolis. All his figures emerge by cracks, by cuts, by accumulations; the faces advance in the guise of votive masks still soaked in ash, and the bodies retain the echo of a lost genealogy, a hidden scaffolding that guides the form without dominating it. His works of the 1950s return a karst movement through a concentration of volume that advances by compressions, thickenings, continuous pressures that rise from the inner core and pour into the protrusions of the face and the folds of the torso. Tension runs through the entire verticality of the figure, granting no respite.

In his Chimera of 1953, the continuity with Etruscan art, one thinks of the Chimera of Arezzo, becomes evident already from a very first and fleeting glimpse: the bronze concedes neither to the fluidity of line nor to the seduction of detail, but is silently arranged as a tight, compact organism, at the limit of combustion. The figure advances according to a decisive front, the torso concentrates its energy in a relief that seems to push outward without ever crossing the threshold of fracture, and each surface retains a restlessness of gesture, a vibration reminiscent of certain presences from Etruscan necropolises, figures that time has stiffened without robbing them of their voice. Basaldella lives matter as if it were a territory to be unearthed: witness those heads that advance according to protruding foreheads, similar to masks chewed by time, and those bodies that maintain a gravity capable of recalling certain Etruscan figures in bronze, beings suspended between humanity and ritual, endowed with a weight that belongs not to mass but to intensity. His works do not pursue purity of form; they remain faithful to a law that prefers density, concentration, the pressure that rises from the heart of sculpture and consoles it against the crumbling of the present.

Later, in the 2000s, Mimmo Paladino also returns to openly confront the Etruscan legacy, translating it into a language to be reactivated. In the works of the Etruscan series, the reference to the ancient does not come through direct quotation. Explicit is the dialogue with the history of Italian sculpture in Etrusco. Homage to Marino Marini. Here Paladino rereads the Tuscan master's lesson by recovering the severe frontality of archaic bronzes, the compactness of horses and that same pressure that holds the body before movement. The proposed figure does not predictably quote Marini, but moves in the same direction of listening, where the archaic is grammar that continues to produce meaning.

In these works, the surface works exactly as an archive or, even better, as a repository of time. The planes preserve traces of etching, opacity, areas of shadow and silence.

And this current, which spans the centuries without ever losing intensity, comes down to us with surprising lucidity. Antony Gormley, with silhouette-like bodies thickened by a firm gravity and his constellations of postures that transform emptiness into matter, belongs to this same line. His sculpture stems from the discipline of measuring oneself against iron, of limning one's body until it is emptied, of putting it back into the world as an elemental structure. In Case for an Angel I of 1989, the figure contains something of the archaic solemnity of the Volterra and Arezzo bronzes. In Field, thousands of terracotta figures return to say what the Chiusi canopic figures had previously intuited: identity living in posture, in the compact mass of presences.

It is in this vast constellation, where the ancient mixes with contemporary iron without ever becoming citation, that Etruria stops being a side chapter of history and imposes itself as a method. A discipline that concerns the way in which the figure accepts to appear, the way in which it delivers itself to the world without guarantees, the way in which it holds its fragility without turning it into ornament.