Dragons in Tuscany: from mythology to the works of the great masters

From the ancient Greek drakon to medieval winged, fire-breathing dragons, Tuscany holds works that chronicle the iconographic evolution of the creature and its symbolic role among courage, faith and virtue. Here are 20 hidden among the region's museums, churches and palaces.

By Noemi Capoccia | 12/12/2025 20:48

The dragon, a mythical figure that has always populated the human imagination, has gone through centuries of iconographic transformations until it became the fire-breathing winged monster we know today. Its presence in the figurative arts recounts a particular evolutionary path: from the ancient Greekdrakon, snake-like and feared for its strength, like the Hydra of Lerna defeated by Hercules, to the medieval creature equipped with bat wings, horns and fiery breath, inspired in part by the terrible descriptions of Leviathan in the Book of Job. Medieval bestiaries codified the image of the dragon as a symbol of evil, providing artists with models of reference that would influence centuries of depictions. Famous examples such as the dragon in Harley manuscript MS 3244, dating from the mid-13th century, already show the appearance we associate with the creatures today: a crocodile-like body, bat-like wings, horns and a fiery mouth.

In Tuscany, museums and collections preserve works that illustrate the figure's evolution. For Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Carlo Dolci, and Piero di Cosimo, the dragon became the protagonist of heroic and mythological narratives, often defeated by saints and heroes. Saint George, revered as a knight and martyr, frees Princess Elisava from a dragon that threatened her city, transforming the creature's terror into a symbol of the victory of good over evil. Similarly, the archangel Michael is depicted as a young armed warrior, engaged in defeating the dragon, the embodiment of evil forces: his images celebrate the triumph of virtue and faith.

Iconographies then expanded with Cornelis Cort, Salvator Rosa, and Giovanni Battista D'Angolo, who reinterpreted the monster in biblical and mythological contexts with great attention to detail and the drama of the scene. The applied arts also celebrate the creature: the jasper vase from the Saracchi workshop, now in the Grand Dukes' Treasury at the Pitti Palace, transforms the dragon into an exercise in technical virtuosity, while in the Contrada del Drago Museum in Siena the fantastical figure becomes an emblem and symbol of community identity. From painting to sculpture, from miniatures to engravings, each depiction shows how the dragon has been a means of embodying evil, fear and, at the same time, the courage and virtue of those who face it. Through the works housed in Tuscany's museums, a rich and varied panorama emerges, where myth, religion and artistic ingenuity intertwine, confirming the eternal appeal of a creature that continues to capture the imagination of the beholder. Here, then, is where dragons hide in Tuscany.

1. Donatello, Saint George (Florence, National Museum of the Bargello)

Donatello 's St. George of 1636, commissioned by the Arte dei Corazzai and now housed in the Museo Nazionale del Bargello in Florence, was originally placed in an outdoor niche in Orsanmichele and later replaced by a copy, shows an innovative approach to sculpture. The sculptor approaches the problem of space differently from the painter or the architect: while the painter creates illusory depth with perspective and the architect defines space through the geometry of the building, the sculptor works on full volume. Donatello structures St. George on a triangular logic: the spread legs form the base, the shield takes up complementary triangles, and the ovoid head and columnar neck fit into this geometry.

The central vertical axis, from the tip of the shield to the head, gives moral stability without rigidity, thanks to the movement of the lateral lines. The statue expresses human virtue: St. George is the protagonist of his own action, victor by rationality and decision, not by divine will. The perspective of the relief at the foot of the statue, with its depiction of St. George and the dragon, with vanishing lines between rock and porch, and the use of light on the concave background, help to give depth and isolate the protagonists, evoking the ancient Roman principle of shaping space with chiaroscuro. The work thus reflects a Renaissance ideal of balance between geometry, virtue, and human experience.

2. Piero di Cosimo, Perseus frees Andromeda (Florence, Uffizi Gallery)

Perseus frees Andromeda by Piero di Cosimo, painted between 1510 and 1515, is a tempera grassa on panel now in the Uffizi. The work recounts one of the best-known episodes of Ovid's Metamorphoses, transforming the myth into a continuous and articulate narrative. The main scene shows Perseus in the act of defeating the sea monster charged with devouring Andromeda, an Ethiopian princess destined for sacrifice to punish the pride of her mother Cassiopeia, guilty of offending Poseidon. The hero appears several times within the same pictorial space: first, he flies over the landscape in winged footwear while spotting the chained maiden, then he fights the dragon (as reported and defined in the work's fact sheet), and finally he celebrates his victory next to liberated Andromeda, his future bride.

The narrative structure is punctuated by strong emotional contrasts. On the right, the exultation of the king and the crowd dominates, while on the left the anguish of the family, aware of the impending sacrifice, prevails. Piero di Cosimo favors a clear reading of the tale, toning down the dramatic tension through a bright, almost pacified seascape, within which the monster appears surprisingly immersed. Probably intended for the decoration of a wedding chamber in the Strozzi Palace, perhaps for the wedding of Filippo Strozzi the Younger and Clarice de' Medici, the panel later reached the Medici collections. It is documented in the Uffizi as early as the late 16th century, displayed in the Tribuna.

3. Cornelis Cort, from Julius Clovius, Saint George and the Dragon (Florence, Uffizi).

Cornelis Cort, a celebrated sixteenth-century Dutch engraver who was active for a long time in Italy, made the 1577 engraving St. George and the Dragon, based on a lost work by Giulio Clovio, a renowned illuminator of the time. The print, kept at the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe in the Uffizi Galleries in Florence, has been in the collection since the second half of the 18th century and is signed and dated by the artist.

The scene echoes the miniature mentioned by Giorgio Vasari in his biography of Clovio, which tells how Cardinal Farnese donated the work depicting St. George to Emperor Maximilian II. Cort's engraving translates into graphic format the delicacy and precision of Clovio's miniatures, offering valuable evidence of the encounter between Italian art and northern engraving mastery in the 16th century.

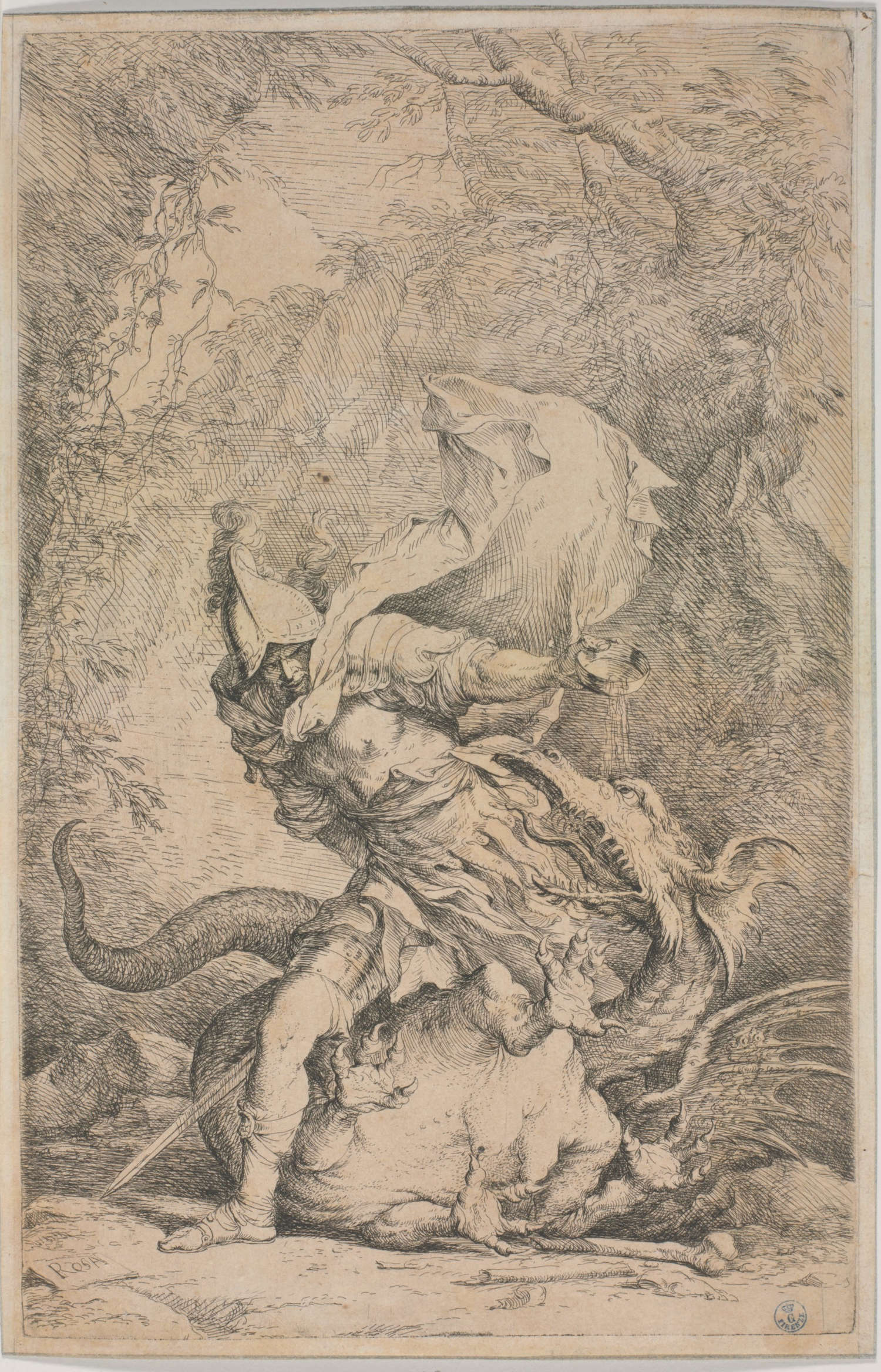

4. Salvator Rosa, Jason Sleeps the Dragon (Florence, Uffizi).

Salvator Rosa's etching and drypoint Jason Sleeps the Dragon, a work of 1663-1664 housed in the Uffizi Galleries, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, Florence, shows the hero during his third venture to win the Golden Fleece. Jason, in the center of the composition, pours the magic potion on the dragon protecting the precious ram's cloak, as the creature slowly succumbs to sleep.

The artist tackles the theme several times, exploring it through preparatory studies, drawings and paintings, highlighting the contrast between heroic tension and the drama of the scene. The work represents Rosa's ability to merge myth and theatricality into an intense narrative, where every gesture and detail concurs to bring the classical legend to life.

5. Giovanni Battista D'Agnolo, Landscape with Saint Theodore and the Dragon (Florence, Uffizi)

Giovanni Battista D'Agnolo, known as del Moro, produced between 1560 and 1570 the etching Landscape with Saint Theodore and the Dragon, now preserved in Florence in the Uffizi Galleries, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe. The etching reproduces an original pen-and-ink drawing by Titian Vecellio, housed at the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. The work shows a soldier in armor engaged in piercing a dragon: it is St. Theodore, not St. George as had long been believed.

A protector of Venice before St. Mark, Theodore is distinguished for defeating the creature with a single blow of his spear, a symbol of courage and faith. The etching highlights D'Agnolo's ability to transfer to metal the Venetian master's energy and composition, with a landscape that expands the scenic space and intensifies the tension of the mythical scene.

6. Carlo Dolci, Saint John the Evangelist in Patmos (Florence, Pitti Palace).

Carlo Dolci's St. John the Evangelist in Patmos, dated 1656, belongs to the collections of the Pitti Palace in Florence and is kept in the Palatine Gallery, Ulysses Room. Executed in oil on copper, a minute format but of great refinement, the painting comes from the collections of Grand Prince Ferdinando de' Medici and is already documented in the 1695 inventory of Poggio Imperiale among the possessions of Vittoria della Rovere. The presence of the metal support, attached to a thin wooden frame, determined its initial description as a panel.

The work precedes two larger canvas versions, now dispersed, made for Pier Francesco Rinuccini and Cardinal Giovan Carlo between 1657 and 1659. The inscription on the frame, with date and time of the start of the work on Holy Thursday, reveals the artist's rigorous method and the devotional value attributed to the pictorial act. The subject originates from Revelation: John, confined to Patmos, witnesses the vision of the woman clothed with the sun, threatened by the seven-headed dragon. The composition is organized in a space suspended between sky and sea, where the figure of the saint emerges in the foreground, held up by the uncertain support on the book. The deliberately emphasized hand gesture becomes the visual center and guides the eye toward the luminous apparition, inspired by Dürer's famous 1498 engraving. Dolci demonstrates absolute expertise in the rendering of details, from the texture of the mantle and the definition of the hair to the dragon and eagle treated in monochrome. The copper dialogues with a carved and gilded wooden frame of remarkable virtuosity, decorated with dragon heads consistent with the iconographic theme. The attribution to Cosimo Fanciullacci remains likely, in light of the affinities with widespread models in late 16th-century Florentine bronze sculpture related to the milieu of Pietro Tacca.

7. Bottega dei Saracchi, Vase with Lid in the Form of a Dragon (Florence, Pitti Palace).

Made in the last quarter of the 16th century, before 1589, the vase in Graubünden jasper with gold, enamel, pearl and ruby applications represents a valuable example of the production of collectibles intended for the great Italian courts. The work, now preserved in the Treasury of the Grand Dukes of the Pitti Palace in Florence, presents a complex structure, conceived as a true exercise in technical and formal virtuosity. A circular foot, embellished with a gold band enameled with plant motifs and set gems, supports a stem articulated by gilded knots decorated with enamel. The bowl, worked in the shape of a shell, houses a lid entirely fashioned as a dragon: the head, wings, and tail are carved in the round and attached by thin gold ligatures. On the back appears a small fantastic creature assimilated to a dolphin, conceived as a functional grip and at the same time as a symbolic element.

The earliest documentary record of the vase appears in the 1589 inventory of the Uffizi Tribune, where the object is described in minute detail for materials and gems. Originally placed in the Tribuna's secret cabinets, it remained in that Medici casket until the late 18th century, when it was transferred to the Cabinet of Gems. The attribution leads back to the Milanese workshop of the Saracchi brothers, well-known carvers and goldsmiths, renowned for vases and sculptures in semi-precious stones with shapes of real and imaginary animals. Similar works, also in the Treasury of the Grand Dukes, suggest production related to the wedding celebrations of Ferdinando I de' Medici with Christina of Lorraine.

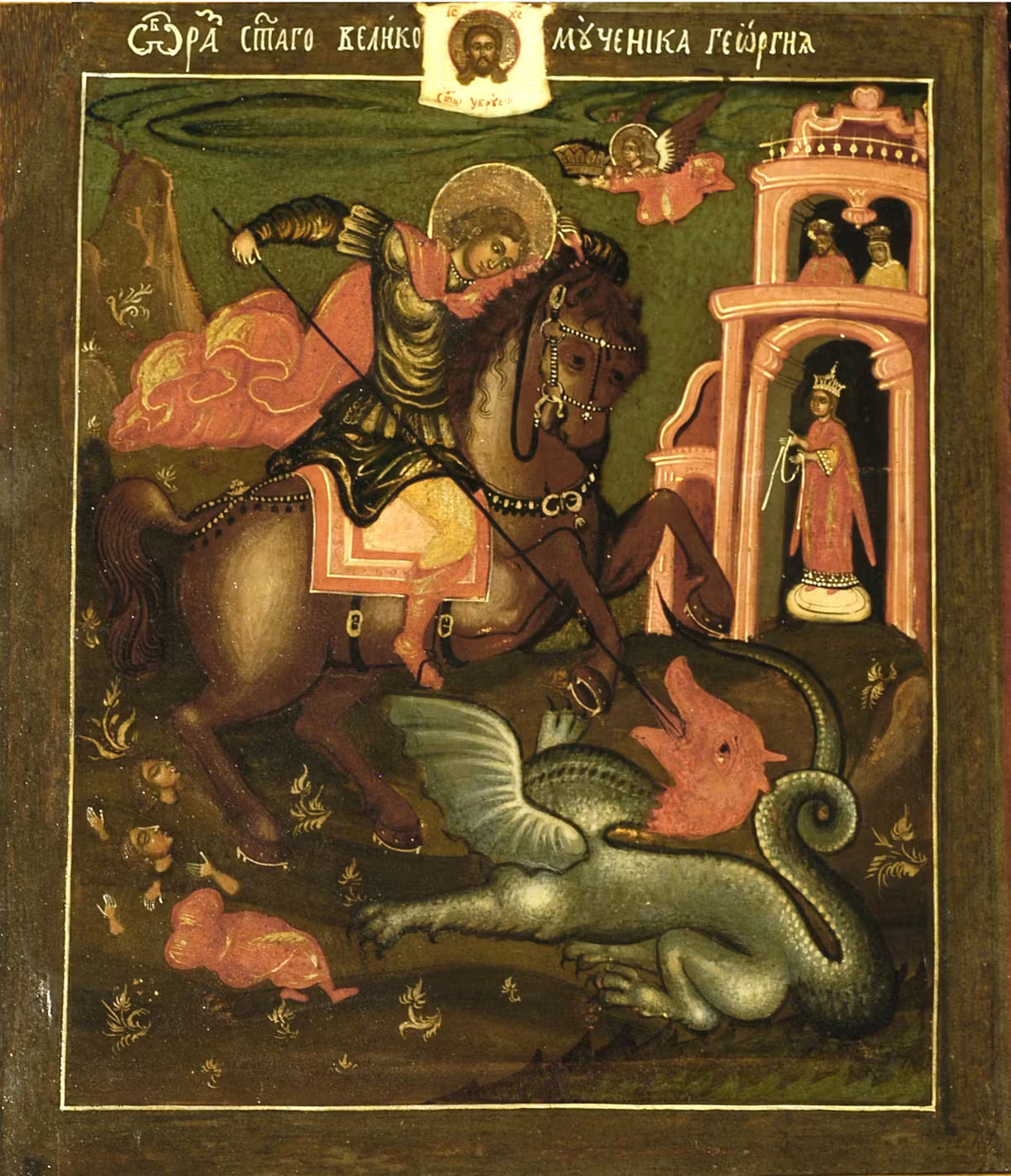

8. Russian Art, St. George pierces the dragon (Florence, Palazzo Pitti, Museum of Russian Icons).

This icon of Russian scope pays homage to St. George, among the most venerated saints in ancient Rus. A fourth-century martyr, an officer in the Roman army and a Christian, he suffered beheading by order of Diocletian. The depiction presents him as an armed knight, symbolizing the victory of good over evil, as he pierces the dragon. The subject derives from hagiographic tales of apocryphal origin. In a city in Asia Minor, a monster demanded the daily sacrifice of young victims. When the fate befell Elisava, daughter of the ruler, George suddenly intervened, felled the creature and had it led into the city, tamed by a belt. The scene includes the princess by the city gate and, above her, the reigning parents. An angel crowns the saint, an allusion to the glory of martyrdom.

Stylistically, the work reveals strong openings to painting between the 17th and 18th centuries: volumetric modeling with a naturalistic imprint, architecture with a Baroque flavor, dynamic tension in the figure of George, the horse's head set in foreshortening, and the dragon rendered with sturdy limbs rather than a winged serpentiform form. The icon, datable to between the third and fourth decades of the eighteenth century, belongs to the collections of the Uffizi Galleries and anticipates a model also widespread in Kostroma and ÄŒerepovec. Singular, and limited to the Florentine example, is the inclusion of the remains of the dragon victims, a detail perhaps suggested by contact with Western figurative culture. The execution should be traced to the same workshop active for other icons now in the Uffizi.

9. Piero del Pollaiolo, St. Michael the Archangel Felling the Dragon (Florence, Museo Bardini).

The Museo Stefano Bardini in Florence preserves Saint Michael the Archangel Felling the Dragon, a masterpiece by Piero del Pollaiolo made between 1460 and 1465. Originally part of a processional banner of the Company of St. Michael the Archangel of Arezzo, the painting was later cut and transformed into an easel work.

After a period in the Campana collection and posthumous auction sale from the Demidov collection in London, it entered the collection of Stefano Bardini, becoming one of the museum's most important pieces. The work, executed in tempera on canvas, shows the archangel Michael in the act of defeating the dragon, combining the precision of anatomical detail with an intense dramatic sense typical of 15th-century Florentine painting.

10. Sano di Pietro, Fight between St. George and the Dragon (Siena, Museo Diocesano)

This tempera panel by Sano di Pietro (1406-1481) depicts the Struggle between St. George and the Dragon and comes from the Sienese church of San Cristoforo, where it occupied the center of an altarpiece commissioned by bequest in his will on August 11, 1440, by Giorgio Tolomei; the executor of the will was his nephew Francesco di Jacopo Tolomei, who took over on August 24 of the same year. Sano di Pietro, active from at least 1428, probably trained with Sassetta, though without reaching his highest achievements, and was influenced by his contemporary Giovanni di Paolo, also working in Siena. The work is now preserved and on view in the Museo Diocesano in Siena.

11. Medallion with dragon (Siena, Contrada del Drago Museum)

The symbol of the Contrada del Dra go in Siena is, of course, the dragon, recalled in every element of the contrada. The museum tour inside the Contrada del Drago Museum, thus winds its way through several buildings located within walking distance of each other. The tour starts from the Oratory, the Contrada's church, and continues to the Hall of Victories, where the Drappelloni conquered over the centuries are kept. It then moves on to theDragon Fountain , whose waters are used every year, during the Festa Titolare, to baptize the new Dragaioli. The Costume Gallery holds historical and contemporary mounts, ancient flags, masgalani and the palii won by the contrada.

The figure of the dragon, the contrada's guide and emblem, is also depicted on a medallion at the entrance to the church of Santa Caterina del Paradiso, at the corner of Piazza Matteotti and Via del Paradiso.

12. Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Triptych of Badia a Rofeno (Asciano, Museo Civico di Palazzo Corboli)

The Triptych of Badia a Rofeno by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, is a two-registered complex consisting of six gilded and painted panels referring to the artist, enclosed within a carved and polychrome wooden frame dating from the early decades of the sixteenth century. The lower register is dominated by the figure of St. Michael the Archangel, depicted as a young warrior in the act of confronting a seven-headed dragon; at the sides appear St. Bartholomew and St. Benedict, on panels of vertical format. On the upper level, within a larger triangular panel, is the Madonna and Child, set in a gilded trefoil arch, now partially veiled by a green background; two small side triangles house St. John the Evangelist and St. Louis of Toulouse.

The particular shape of the ensemble and the transformations it underwent in the 16th century have fueled a long debate about the polyptych's original appearance. Initially assigned to unknown Sienese masters, it was De Nicola who traced it back to Ambrogio Lorenzetti, hypothesizing later interventions that would have altered the shape and proportions of the panels. Other readings, including Carli's, suggest a different provenance from the Badia di Rofeno and explain the iconographic alterations in relation to the monastic complex's dedications. Investigations conducted during the restoration excluded some earlier reconstructions, confirming the structural unity of the upper panels. The work is now preserved at the Museo Civico di Palazzo Corboli in Asciano (Siena) and almost unanimously attributed to Ambrogio Lorenzetti and workshop, despite some alternative proposals. The monumental frame, probably the work of Fra Raffaello da Brescia, integrates grotesque motifs, gilded pinnacles and an ornate predella, creating a refined link between 14th-century painting and Renaissance carving.

13. Buonamico Buffalmacco, Saint Michael Archangel (Arezzo, Museo nazionale d'arte Medievale e Moderna).

For a long time attributed to Giovanni d'Agnolo di Balduccio or Parri di Spinello da Del Vita, and later to a Florentine school of the second quarter of the 14th century with references to Bernardo Daddi and an unknown Sienese painter, today the panel San Michele Arcangelo, is recognized by Miklòs Boskovits as the work of Buonamico di Martino, known as Buffalmacco. Probably commissioned for the destroyed church of Sant'Angelo in Archaltis, where the Fraternita dei Laici had a chapel, it was moved to the institution's main headquarters near the gate of the same name in the area now occupied by the fortress. Restoration in 1918, conducted by Domenico Fiscali to repair damage from a fire (possibly that of the Fraternita's library in 1759), included the transfer to a new support; the covering pictorial interventions were removed by Carlo Guido in the 1980s.

The work can be dated to the years 1320-25, a period when Buffalmacco was working in Arezzo for the Cathedral at the invitation of Bishop Tarlati, and probably met Andrea di Nerio. The work's influence is evidenced by the sculpture of the archangel for the door of Sant'Angelo in Archaltis, made by the so-called Master of St. Michael, clearly derived from the pictorial model, albeit with different proportions.

14. Sassetta, Madonna and Child, Two Angels and Saints (Cortona, Museo Diocesano)

The polyptych made by Stefano di Giovanni di Consolo da Cortona, known as Sassetta, dates from the second quarter of the 15th century, between 1434 and 1435. The work, executed on wood panel and measuring 134 × 244 cm, brings together several sacred scenes, including the Madonna and Child and two musician angels, St. Nicholas of Bari and the Archangel Michael killing the dragon at his feet, St. John the Baptist and St. Margaret of Antioch, Announcing Angel, Agnus Dei, and Mary the Virgin Announced.

The stylistic quality and bibliographic sources confirm its attribution to Sassetta, a leading artist in 15th-century Sienese painting. Originally placed in the Church of San Domenico in Cortona, the polyptych is now preserved in the Diocesan Museum of the same city, where it continues to bear witness to the master's refined fusion of spirituality and visual poetics.

15. Bartolomeo della Gatta, Archangel Saint Michael (Castiglion Fiorentino, Pinacoteca Comunale)

Bartolomeo della Gatta, born as Pietro di Antonio Dei (Florence, 1448 - Arezzo, 1502), was a painter, miniaturist, clergyman, and architect. He worked mainly in eastern Tuscany, with intense activity in Arezzo and various towns in the Arezzo area, including Sansepolcro, Cortona, Castiglion Fiorentino and Marciano della Chiana. His achievements can also be found in Rome, where he collaborated on the decoration of the Sistine Chapel, and in Urbino.

The tempera and oil panel Archangel St. Michael, now in the Pinacoteca Comunale in Castiglion Fiorentino(Arezzo), comes from the ancient Pieve di San Giuliano and is dated 1480. The image shows the Archangel Michael, patron saint of Castiglion Fiorentino, in the act of triumphing over the dragon that embodies Evil. Next to the celestial figure is depicted a young mother with an infant: this is Teodora, daughter of Lorenza Guiducci, who commissioned the work, and Paolino Visconti, a member of the Milanese troops present in Castiglion Fiorentino during the conflict with Florence. The panel reveals the graphic skill and chromatic vividness that distinguish Bartolomeo della Gatta's work.

16. Andrea di Giusto, Madonna and Child with Saints (Prato, Museo di Palazzo Pretorio)

A pupil of Bicci di Lorenzo and collaborator of Masaccio in Pisa, Andrea di Giusto, known as Andrea da Firenze, was a painter straddling the Gothic tradition and Renaissance influences, also known as a skilled copyist. For this reason, the Olivetan monks of the Monastery of the Sacca, near Prato, entrusted him with the replication of Lorenzo Monaco's famous polyptych made in 1411 for Monteoliveto (now in the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence). Andrea faithfully reproduced the main figures with vivid color and minuteness, modifying some faces, such as replacing St. Thaddeus with St. Margaret. The Nativity in the predella recalls the nocturnal settings of Lorenzo Monaco, while other episodes show the influence of Beato Angelico, including theImposition of the Name on St. John the Baptist, traced from a compartment preserved in San Marco.

This is followed by the Nativity, Saints Placidus and Maurus, the death of St. Benedict, and the life of St. Margaret, who rejected the love of the prefect Olibrio and suffered imprisonment and beheading. In the three central cusps God the Father blessing is flanked by the proclaiming angel and the Virgin. Completed in 1435, the polyptych opened to Andrea another prestigious commission, the completion of the frescoes in the Chapel of the Assumption, interrupted by Paolo Uccello. The City of Prato purchased the triptych in 1870 from the Cicognini College, where it had arrived in 1775 from the former Olivetan monastery of San Bartolomeo delle Sacca. It is currently kept at the Museum of Palazzo Pretorio.

17. Guido da Como (manner), Saint Michael Archangel (Pistoia, San Michele in Cioncio).

The sculpture, dated around 1250 and placed above the only door of the facade of the ancient church of San Michele in Cioncio in Pistoia, now dedicated to St. Joseph, is photographically documented in its original location by art historian Adolfo Venturi. It has been attributed to an unknown scarpellino, while others highlight its quality, speaking of a good Pisan school. Venturi instead links it, together with the sculptures of the door of San Pietro Maggiore, to an artist close to Guido da Como, author around 1250 of the pulpit of San Bartolomeo in Pantano.

Most later critics refer instead to Guido da Siena. The depiction of St. Michael slaying the Dragon, made of marble and wood with carving, painting and gilding, testifies to the spread of the cult of the Archangel in the city.

18. Buonamico Buffalmacco, Last Judgment (Pisa, Camposanto Monumentale)

TheLast Judgment at the Monumental Cemetery in Pisa is the most famous piece in the cycle known as the Triumph of Death, attributed to Buonamico Buffalmacco. In the complex, already partially reassembled with the scenes of the Stories of the Holy Fathers andHell, a theatrical setting emerges: on the right the damned, on the left the blessed, divided by the Archangel Michael. At the top, the Virgin and Christ the Judge dominate the entire composition, flanked by the apostles and a host of angels raising the instruments of the Passion and recalling the ultimate meaning of Redemption.

At the center of the damned appears a monumental Lucifer, twice as tall as the Christ figure. He embodies pride, the root of all vice, and appears as a green dragon, with serpentine horns and scales, in the act of devouring a damned. The image, once accompanied by explanatory inscriptions, involved the viewer, inviting him to compare his own life with what is depicted, in a moral journey similar to that made famous by the Divine Comedy.

In the 14th century the walls of the Cemetery were enriched with frescoes dedicated to the relationship between Life and Death, executed by Francesco Traini and Buffalmacco himself. Their works translated into images the preaching of the Dominican Cavalca and Dante's visions, particularly recognizable precisely in theTriumph of Death and the Last Judgment.

19. Francesco Traini, Saint Michael Archangel (Lucca, National Museum of Villa Guinigi).

This tempera panel preserved at the National Museum of Villa Guinigi in Lucca shows Saint Michael in the act of plunging his spear into the dragon at his feet. The creature has a teal body and wings with cartilage highlighted by white lead elevations. The archangel wears a light blue robe with folds rendered by the same technique; the outer wings pick up the tone of the robe, while the inner wings fade from near-white upper to dark brown lower, with feathers emphasized by darker touches. Two decorative bands, horizontal and vertical, appear in dark brown, a color that returns in the fibula that closes the rosy mantle.

The work, of fine execution, was attributed by Mario Bucci to Francesceso Traini on the recommendation of Roberto Longhi. The most convincing dating places it around the middle of the fifth decade, in relation to the Pisa polyptych with the Glory of St. Dominic. The panel still reflects the influence of Simone Martini, especially in the similarities with the Avignonese production of the master and Giovannetti. Angelo Tartuferi proposes a chronological approximation to the Holy Bishop already in Santa Felicita. Probably present in Lucca from its origins, the painting must have influenced painters active in the area such as Angelo Puccinelli (De Marchi 1998) and figures close to the so-called master of San Frediano. Coming from the Convento dell'Angelo in the mountains of Brancoli, it passed temporarily to the Museo di San Matteo and then came to Villa Guinigi, a location more consistent with its origin. The altar table by Priamo della Quercia and the laterals by Gherardo Starnina also come from the church of Tramonte.

20. Bottega di Guidetto, Stylophorus lion fighting a two-headed dragon (Borgo a Mozzano, Pieve di Santa Maria Assunta)

The stylophorous lion fighting a two-headed dragon is carved in limestone by Guidetto and his workshop between the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Belonging to the Italian school with Lombard influences, the work is located in the nave, at the edge of the chancel, of the Pieve diSanta Maria Assunta in Diecimo, in the territory of Borgo a Mozzano (Lucca). Guidetto's production, among the highest expressions of early 13th-century Tuscan sculpture, is distinguished by the renewal of pulpits, which rework earlier models such as Guglielmo's grandiose ones for Pisa, adapting them to Lombard ideologies and plastic languages.

Guglielmo's dynamic and lively fairs here yield to a more static monumentality, with an intense use of the chisel. The lion, with its mane neatly curled, appears muscular and firm on its base, while the two-headed (two-headed) dragon reacts by biting its lower lip and stinging its thigh. Both lions, along with the strapping figure of Isaiah, came from the original pulpit dismembered in 1675, the existence of which is documented in the 1348 will of Bartolomeo Proficati of Lucca.