The dream of Villa Cordellina Lombardi, where Tiepolo's genius overcame decay

From ruin to rediscovered magnificence thanks to a generous entrepreneur and those who kept its spirit alive: the story of the splendid Villa Cordellina Lombardi in Montecchio Maggiore (Vicenza) is a journey between the genius of Tiepolo, the ambition of a great lawyer and the power of collective protection. Federico Giannini discusses it in the new article in his column The Ways of Silence.

By Federico Giannini | 04/01/2026 16:15

Dust, damp patches, dirt encrustations, cobwebs, walls covered with lime, Giambattista Tiepolo's frescoes hidden by heavy metal grates. Those who, at the beginning of the twentieth century, had entered Villa Cordellina, a splendid neo-Palladian residence in Montecchio Maggiore, about twenty munti from the center of Vicenza, would have found this mortifying, painful situation. An encroaching, total degradation that had seriously endangered the bewitching Tiepole paintings. And anyone who had knowledge of what was happening to the villa's salons could not help but express their despondency.

A few years earlier, toward the end of the 19th century, the board of trustees of the college to which the fate of the villa had been entrusted by the will of the last owner, Count Niccolò Bissari, who died in 1829, had decided to lease the villa to a Vittorio Veneto firm, the "Premiato Stabilimento Bacologico Costantini," which implanted a silkworm farm in the halls. At that time, safeguarding the environments was not supposed to be the priority: maintaining the villa cost money, the college had few resources, and Veneto was at that time an impoverished land, a difficult land, a land that had recently freed itself from the burden of decades of Austrian rule. Land of emigration. The idea of having a company open a factory that would employ more than a hundred female workers in a job-starved province must have seemed most reasonable to everyone. It cannot be said, however, that the college had not thought about the frescoes: the Costantini factory was able to operate on the condition of installing false ceilings in all the halls and shielding Tiepolo's paintings. However, the measures were not enough to prevent the building, its halls, and the paintings from being damaged.

Villa Cordellina has flourished again today. We should, however, more properly call it Villa Cordellina Lombardi, with the name it has assumed to pay homage to that Vittorio Lombardi who bought it in 1953 and who spent so much money on it. It is now the property of the Province of Vicenza, and there is almost nothing to allow us to imagine what it went through in the early part of the twentieth century. Of course: as we walk through the rooms, we notice that all the 18th-century furnishings are missing. Only the chandeliers are left, large Murano glass chandeliers that date from Villa Cordellina's first season. Otherwise, the guide who accompanies me on a tour of the villa tells me, all the furniture we see is irrelevant. Some walls still appear slightly blackened. In the garden, statues bear the marks of centuries. But the overall situation looks excellent.

From the center of Montecchio, one can also reach Villa Cordellina on foot: however, the navigator, set to the official address, leads to the parking lot at the back, because today the offices are in the outbuildings of the villa, in those Baroque-style annexes, and consequently the entrance is from the northern front of the villa. Although the appearance of the back is still magnificent: like most Palladian villas, Villa Cordellina Lombardi has two facades, equally splendid. Lawyer Carlo Cordellina, the building's founder, wanted everyone to see, from all sides, the standard of living he had been able to achieve. The lawyer was a homo novus of the rich Venetian bourgeoisie: he was born in Venice, but was from a Vicenza family, a well-to-do family that had always lived decently, even managing to obtain from the city of Vicenza the privilege of nobility in the early eighteenth century, but which was not among the richest, nor among the most influential. Things changed with Charles: he had studied law like his father Ludovico, also a lawyer, but unlike his parent he managed to become, his biographers tell us, one of the most famous and sought-after jurists in the Veneto. They describe him as a man of good looks, a good and generous soul, gifted with a great deal of acumen, an acumen that evidently served him to establish himself as the best lawyer in Venice and to accumulate, thanks to his profession, such riches that he was able tohire one of the best architects of the time, Giorgio Massari, an advocate of the Palladian tradition (but capable of combining them with a seventeenth-eighteenth-century taste, evident especially in the barchesse, where Cordellina had the stables and guest quarters arranged), and the best painter on the square, Giambattista Tiepolo, to fresco the largest salon. When the work started it was 1735. And the lawyer was just 32 years old.

We know that eight years later the villa was ready for Tiepolo's work and fifteen years later it was finally habitable, although the work would not be completed until 1760. Cordellina had chosen to build his villa on land he had inherited from an uncle, where there was already an old house, in the middle of the plain on which the village of Montecchio stands, with the Lessini mountains on one side and the Berici mountains on the other, and above all in the middle of the two roads from which the building can still be reached today: the lawyer evidently appreciated the convenience of that location. However, the guidebook points out to me, like all homines novi (those who wish to malign them would call them parvenu), Cordellina too, even in all his nobility of spirit, must have felt the need to flaunt the status achieved by the family: the location was also strategic for being seen. And his family coat of arms, three hearts from which sprout three flax plants (an obvious reference to his surname), stands out on the tympanum of the southern facade, the main one, although in ancient times it must have also stood out on the back, where there is now a large empty oval. The facades are reminiscent of an ancient temple: the main one is preceded by a large pronaos with Ionic columns supporting the tympanum on which the three statues depicting Jupiter, Mercury and Minerva stand out, while the northern facade repeats the same scheme, but replacing the pronaos with a more advanced body, marked by four pilasters on which the tympanum, crowned by three vases, is grafted. Even the iconographic program of the sculptural apparatus, the work of the workshop of Antonio and Francesco Bonazza, should be imagined as an exaltation of the virtues of the founder of the villa, as a manifesto of his qualities, as a summary of his life and the values in which he believed, as a lawyer and as a man. Beginning with the very statues on the facade: Mercury is the god of commerce, the activity at the origins of the family's wealth, but he is also the god of eloquence, a fundamental faculty for a lawyer. Minerva is the goddess of wisdom, reason, and prudence, indispensable qualities for success at work (and, for a lawyer, for making the right decisions at trial), as well as for preserving family wealth. Jupiter is the supreme authority, the guarantor of order and law. In the garden, we see on the one hand the sculptural group with the love between Venus and Mars (beauty taming war, and thus civilization taming the most feral instincts of human beings, but also conflict resolution, the ultimate goal of the work of'a lawyer) and on the other the love between Jupiter and Juno (marital love, legitimate, a sign of order and stability, with Juno embodying parental love and care for the home, and Jupiter the protection of the family). The entrance is flanked by two other groups, with two Labors of Hercules, allegories of the commitment and difficulties Cordellina had faced and overcome to establish herself. It was by passing these statues that visitors, after leaving their horses in the stables, now converted into a lush lemon grove, entered the villa.

More than a hundred years ago there was nothing left of the magnificence that must have reigned here when the lawyer received his guests. In 1909, Pompeo Molmenti, a passionate scholar of Tiepolo, had visited Villa Cordellina, and in his monograph on the painter he had not hidden his displeasure at seeing how that residence praised by all for its splendor had been reduced, and in what state those much-celebrated frescoes were in: "Although offended by the ravages of time and the graver ones of men, the frescoes in the Villa Cordellina at Montecchio Maggiore, ten kilometers from Vicenza, still reveal the seductive power of the master. The villa's hall empty of furniture exhales a sense of squalor. The ceiling plaster is cracking from dampness, and some pieces have already peeled off, but among so much ruin Tiepolo's full, ringing, gangly color still shines." Four years earlier, a local nobleman, Guardino Colleoni, had already asked the Vicenza city council to do something about the frescoes. It would not be until 1917 that the city would heed that alarm: the ceiling fresco, which had suffered most from water infiltration, was detached and transported to canvas, and hospitalized at Palazzo Chiericati in Vicenza until 1956, when it returned to the villa after a quick cleaning. The frescoes on the side walls have since been restored as well, and several times (most recently in 2004). And today, although no longer as vivid, brilliant and crystalline as they must have been in 1744, Tiepolo's great wall paintings manage to shed their clear light on the eyes of anyone who enters here, in the hall of honor of Villa Cordellina.

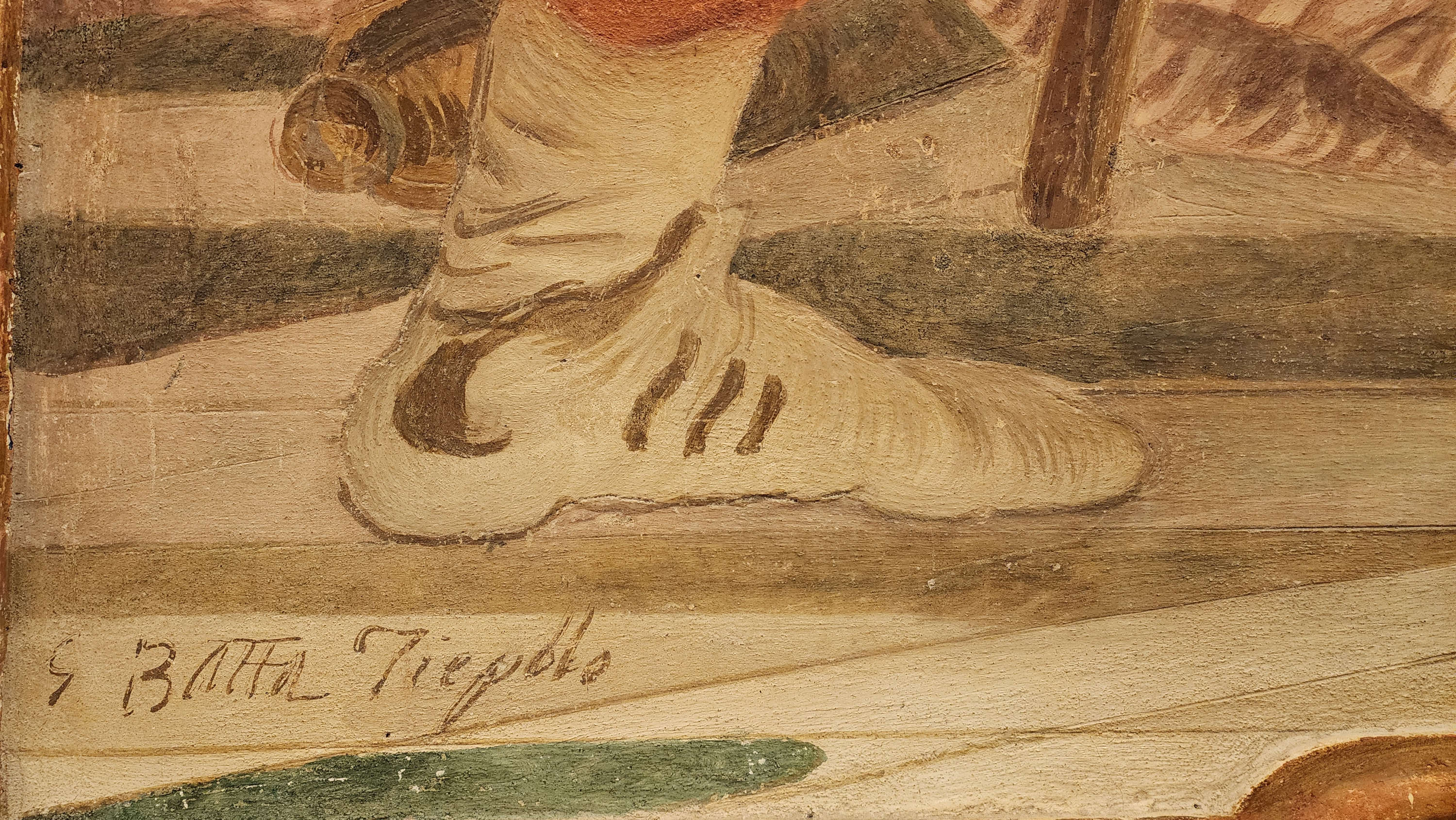

Given the profoundly Enlightenment spirit of the frescoes, the program was most likely suggested to Tiepolo by the writer Francesco Algarotti, his friend, with whom the artist was in contact at the very time of the Montecchio paintings, if not by Carlo Cordellina himself: Tiepolo's work celebrates the light of intelligence that illuminates the darkness of ignorance and by its glow irradiates and directs human activities in all parts of the known world. The reading begins from the ceiling: an auroral sky where two maidens, one blonde and one brunette, fly toward the earth, with ignorance lower down, already defeated and confined in darkness with its bat. They carry in their hands a statuette of Pallas, the symbol of reason: the two young women, accompanied by fame and two cupids who are already ready to bestow crowns and medals, are about to distribute the gifts of reason in the world, represented by the four monochromes with the allegories of the continents in the corners of the hall. The effects can be seen on the two side walls, one occupied by the scene with the Continence of Scipio, the other with the episode of the Family of Darius before Alexander the Great: two paintings extolling the magnanimity of the two commanders, Scipio for respecting a beautiful girl who had been handed over to him as a slave by allowing her to be reunited with her parents and fiancé, and Alexander the Great for using clemency toward the mother and daughters of Darius, his bitter enemy defeated at the Battle of Issus. The scholar Remo Schiavo, who has devoted dense pages to Villa Cordellina, has suggested reading into the two scenes, thinking of the patron's profession, the idea of natural law getting the better of positive law, the two commanders making the customs of the people they subjected prevail over the rights that the law accorded to the victor: and indeed, one could broaden this interpretation by noting how theimperium, represented by the fascio littorio that one of Scipio's soldiers holds in his hands, slips away, into the background, almost hard to notice. Vittorio Sgarbi has read in the two frescoes, in addition to the Christian declination of a pagan subject, the manifestation of a continence that moves from the content to the form, since here Tiepolo renounces his virtuosity to remain solemn, almost severe, in a sort of comparison, we might add, with the painting of the great sixteenth century, with Veronese above all. Yet the artist does not renounce his quickness, his lightness (look at the marks of his engravings that stand out clearly on the walls), and there is no lack of excerpts of his proverbial irony either: Alexander looking into the horse's face so as not to be distracted by the beauty of Darius' sister. The page who, far from sharing in the gravity of the moment, plays with the little dog, a lapdog as was fashionable in the 18th century. In the other fresco, the servant rummaging through the war trophies.

In both paintings, the female groups occupy the exact center of the composition, under the large classical arches, closer in the fresco with Scipio and more defiladed in that with Alessandro (which owes much to the large canvas on the same subject that Veronese painted for the Pisani family and which Goethe admired during his trip to Venice), with the women caught in a supplicating but composed, proud, and even tetral attitude, since every gesture appears slightly calibrated and accentuated, dressed in unreal clothes that seem almost to swell the more one gets closer to see those iridescent cascades of silks and satins in soft, metallic colors, under the Persian flags that stand out at an angle against the staff of Alexander's tent, with the same pose as the ancient statues in theScipio fresco, with their proceeding toward the two condottieri who stand defiladed, on either side of the composition, because Tiepolo had studied his direction of the paintings by imagining Carlo Cordellina's guests would enter the salon from the short side and reach the center by walking on the diagonal. It is as if Tiepolo was having us make the same movements as the women walking toward Scipio and Alexander the Great. And it is almost as if he intended to give the women an ascendancy over the male. Again, Venus taming Mars.

Tiepolo had claimed those two scenes with obvious vigor, affixing his signature to the fresco of Scipio, below the servant with the shoe that looks like a contemporary sneaker (complete with identifiable brand name). Evidently, those frescoes, too, had contributed to making Villa Cordellina one of the central places of Venetian social life in the second half of the 18th century. Carlo Cordellina's receptions must have left a deep impression: "The Villa Cordellina of Montecchio will always be memorable," wrote the lawyer's first biographer, Giovanbattista Fontanella, in 1801, "where generous hospitality was used , where liberality, the comforts of life, the banishment of all etiquette and troublesome ceremonies, and festive noble cheerfulness, made it the delight of all guests." This delight was short-lived, however.

The lawyer had passed away in 1794, and three years later his son Ludovico, bereft of heirs, was already making a will in favor of four people close to him: to collect his inheritance would come in two, Margherita Martinengo and Niccolò Bissari, who divided up the villa. Years later, with Bissari's death, the villa passed by will to the college that would take the name "Opera Pia Cordellina," and the subsequent history has been mentioned. The silkworm farm would remain inside the building until the 1920s, then Villa Cordellina was abandoned. It fell into disrepair. The guide tells me that it was also occupied by the Germans during World War II. And while the war was still going on, in 1943, it was bought by the Marzotto Woolen Mill, which turned it into a grain warehouse. There were still the grates on the frescoes by Tiepolo. And if we see the villa today almost as it must have been at the time of lawyer Cordellina, it is by a fortuitous chance. Of course: changes in sensibility towards the art of the past would inevitably have suggested, sooner or later, the full restoration of Villa Cordellina. However, it is also true that the salvage dates from some time before this sensibility became more common than it once was.

Legend has it that in 1953 the villa was noticed by a Milanese industrialist who was returning from vacation at his home in Cortina. His name was Vittorio Lombardi, he was a major shareholder in Liquigas, and he also went down in history for his boundless passion for mountaineering: it was he who financed the 1954 K2 expedition, the one led by Ardito Desio, that of Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli, the two Italians who conquered the second highest mountain on earth for the first time. Lombardi had only fallen in love with Villa Cordellina as he passed by it while planning the mission to the Karakorum peaks. "At the bottom of an uncultivated meadow," he would say, in the words reported by his friend Dino Buzzati, "there was a villa in fearful abandonment. But even in such destruction and abandonment the factory retained a solemn and bitter dignity of a queen ousted and alone, like a beautiful wounded woman. It was as if I had seen on the roadside a dying woman. The need to come to her aid was stronger than me." He decided to buy it immediately and have it restored: it was in those years that the first, great recovery of Villa Cordellina took place. Lombardi decided to devote part of it to his own lodgings and part to the headquarters of an international center for architectural studies, dedicated to Palladio: we can imagine that this sensibility had matured after visiting the great exhibition on the Venetian villas, curated by Giuseppe Mazzotti, which had been held in various venues (Milan was among them) in 1952. It was an exhibition that also aimed to inform and interest the public about the condition of the villas, so much so that in the catalog each card provided, albeit briefly, information on the state of conservation. For Villa Cordellina, the card closed with the words, "Poor condition."

Lombardi would not be in time to see the fruits of his generosity, because he disappeared in 1957, with the restoration almost completed. The "Andrea Palladio" International Center for Architectural Studies would be established the following year, and in 1959 he took possession of the villa, which his widow, Anna Maria Spangher, had granted in its entirety to the newly founded institute. It would remain there for ten years, before being moved to its present location in downtown Vicenza. Then, in 1970, following Mrs. Spangher's wishes, the villa passed to the Province of Vicenza, the current owner, which uses it as a representative office, as well as opening it to the public, entrusting its visits to the Pro Loco of Montecchio. It includes my guide, a 30-year-old who has no art-historical training, working in a completely different field, but has decided, she explains, to lend part of her free time to this place because she cares. An ongoing collaboration between scholars and volunteers, mostly twenty to thirty-somethings who work in the area, and who continually update themselves to bring visitors inside Villa Cordellina Lombardi: it is the way they have found to remind us that preservation is a collective responsibility, to thank those who have made it possible to keep this legacy alive, and to preserve, to cherish, to perpetuate the spirit of those who resurrected it.