Holy Trinity from Lorenzo Monaco to Beato Angelico: the secret workshop of the Renaissance

In the heart of 15th-century Florence, the art of Lorenzo Monaco, Gentile da Fabriano and Beato Angelico unveiled, in the same place, the church of Santa Trinita, and in less than fifteen years, the transition from the Gothic dream to the new Renaissance rationality. The recent exhibition on Beato Angelico underscored the importance of this place of elaboration of novelties.

By Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta | 21/10/2025 17:51

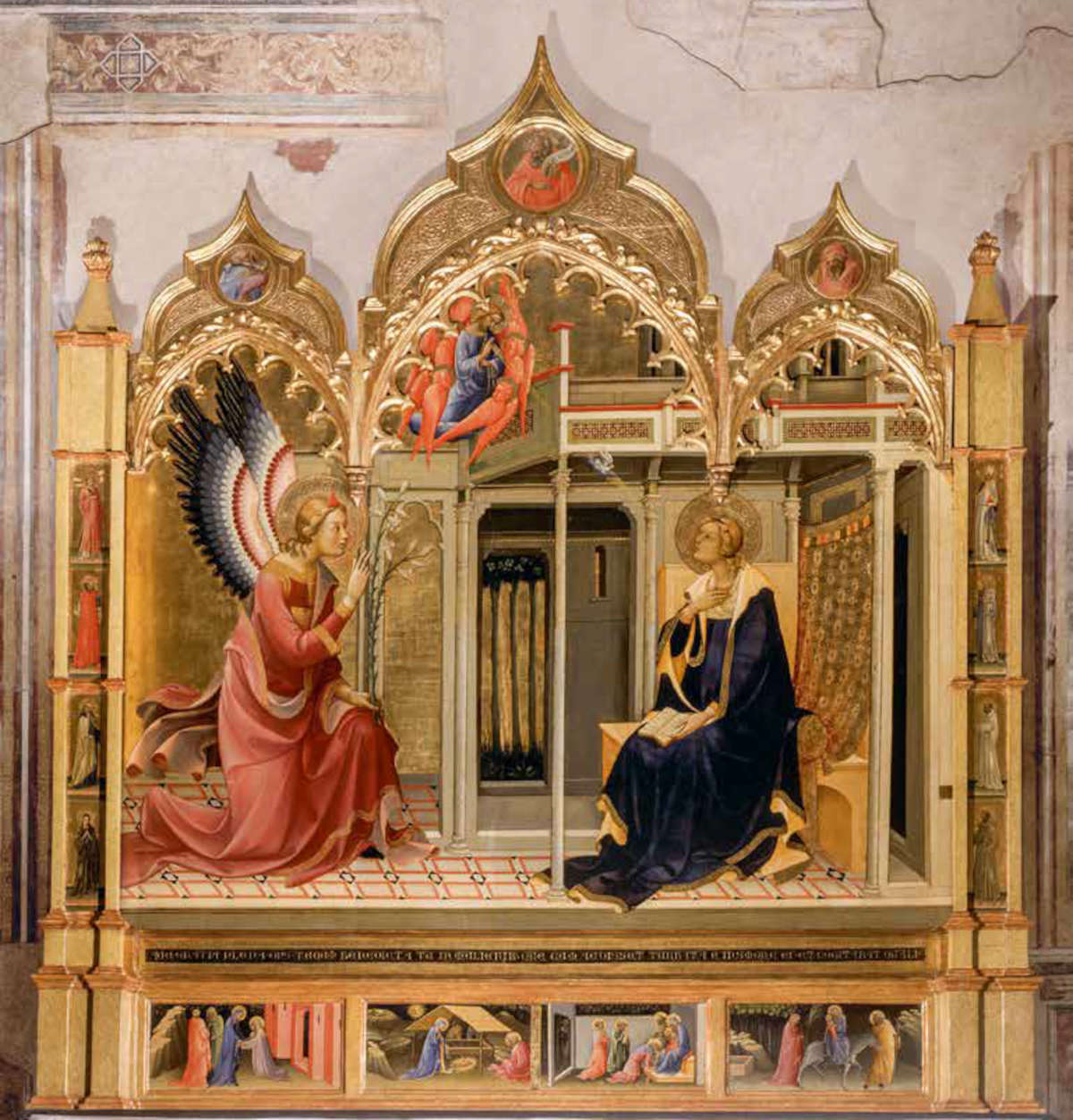

The major 2025 exhibition on Fra Angelico in Florence (Palazzo Strozzi and Museo di San Marco, Sept. 26, 2025 to Jan. 25, 2026) had, among others, the merit of offering the public, in the first room of Palazzo Strozzi, a kind of ideal reconstruction of the church of Santa Trinita in the early fifteenth century, when anyone who entered would have seen three stunning masterpieces of the early part of the fifteenth century, namely theAnnunciation by Lorenzo Monaco (Piero di Giovanni; Siena, c. 1370 - Florence, c. 1424), Gentile da Fabriano 'sAdoration of the Magi (Gentile di Niccolò di Giovanni di Massio; Fabriano, c. 1370 - Rome, 1427) and Blessed Angelico 's Deposition (Giovanni da Fiesole, born Guido di Pietro; Vicchio, c. 1395 - Rome, 1455), three works now all conserved in different places, though all in Florence (theAnnunciation remains in Santa Trinita, theAdoration is in the Uffizi and the Deposition is housed in the Museo di San Marco). The exhibition brought together the altarpieces by Lorenzo Monaco and Beato Angelico, which, moreover, stand, we might say, in ideal continuity, and not only because of the hypotheses of Angelico's alumnae at Lorenzo Monaco's workshop (although the exhibition, in the first section on the early phase of Guido di Pietro's career, curated by Angelo Tartuferi, embraced, if anything, the'idea of a debut in the sign of Gherardo Starnina), but also because of the fact that Angelico took over from his colleague in the realization of the Deposition, which was initially commissioned to Lorenzo Monaco himself. The room then showed, in place of Gentile da Fabriano'sAdoration of the Magi , which remains in the Uffizi, the panel with the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple, now in the Louvre, which formed the right-hand compartment of the predella of theAdoration.

Santa Trinita is a fundamental episode for understanding the intersections of early fifteenth-century Florentine art, suspended between fourteenth-century permanences (the late Gothic taste was still reigning, despite the fact that Masaccio's Renaissance revolution had already taken place) and radical openings to the new. And within a little more than a decade the church had filled with these three cornerstones of Florentine art. The first work to arrive was Lorenzo Monaco'sAnnunciation , still in the Bartolini Salimbeni chapel, which is still the only chapel in the church, explained scholar Daniela Parenti, "to present organically the appearance it took on at thebeginning of the 15th century [...], the result of a homogeneous design, as can be seen from the perfect setting of the altarpiece in relation to the frescoes and the iconographic coherence of the decorative program dedicated to Mary, whose sinless nature is celebrated." The Bartolini Salimbeni family held the juspatronage of the chapel since 1363, although the terms of the commission given to Lorenzo Monaco are unfortunately not documented, and consequently the altarpiece can only be dated hypothetically, on a stylistic basis. This is a highly experimental painting: the artist, while not renouncing his ethereal, almost abstract figures, his flutterings, his elongated proportions, and while not yet applying scientific perspective, nevertheless decides to break the traditional division into compartments of late Gothic art and to insert a scene that is seamless. Indeed: the radical nature of this approach is even evidenced by the lack of symmetry, with the Virgin appearing shifted toward the center and not occupying, in symmetry with the angel, the space below the right compartment. It is possible to imagine that Lorenzo Monaco opted for this solution in order to return to his patron a scene in continuity with the frescoes in the chapel, painted by himself (they are, moreover, the only frescoes by Lorenzo Monaco that we know of).

It is safe to assume, as scholar Carl Brandon Strehlke, curator of the Beato Angelico review, speculates, that Lorenzo Monaco's altarpiece may have been an inspiration to one of the most powerful men in Florence at the time (as well as the city's wealthiest: we know from taxpayer censuses), Palla Strozzi (Florence, 1372 - Padua, 1462), who intended to pay tribute to his father Nofri (Onofrio) Strozzi with an altarpiece that would adorn his burial chapel, also in Santa Trinita. Nofri Strozzi had passed away in 1418 and, in that same year, Palla had decided to enlarge the burial shrine to carry out his father's wishes, who had provided a bequest of two thousand florins for the purpose (to give anidea of the importance of the sum, consider that, in 1420, Ghiberti, Brunelleschi and the master builder Battista d'Antonio, called to oversee the work on the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, were paid a salary of three florins a month). The project, which has been attributed to Lorenzo Ghiberti, involved the construction of a new room, a sacristy, built on an unbuilt area, and the placement of Nofri Strozzi's tomb in the existing chapel, dedicated to Saints Onofrio and Nicola di Bari (the eponymous saints of Nofri and his son Niccolò, who died prematurely in 1411), which would turn out to be adjacent to the sacristy following the work. Palla Strozzi had commissioned Lorenzo Monaco to paint the Deposition, destined for the chapel of Saints Onofrio and Nicholas (where the faithful would have seen it behind a large wrought-iron gate, no longer extant), and Gentile da Fabriano to paint theAdoration of the Magi, which would instead decorate the adjacent chapel. Nofri Strozzi's arcosolium would have divided the two communicating rooms.

First, Gentile da Fabriano'sAdoration was commissioned and completed, painted between 1420 and 1423. It could almost be considered a synthesis of Palla Strozzi's aspirations: Preciosity, applications of gold and silver, an aristocratic procession that seems almost straight out of a courtly fairy tale, the richly harnessed horses, the exotic elements (such as the cheetah watching a falcon catching a pigeon, or the camels with monkeys on their humps, and then the clothes of every shape and color), and even the portrait of Palla Strozzi (he is the man with the unique blue and gold turban seen just behind the magi: curious, on the other hand, that the portraits of Nofri and Niccolò do not appear in theAdoration ), all against the background of an imaginary Florence as seen especially in the predella compartment depicting the Presentation in the Temple, where rich ladies and beggars coexist, probably in keeping with the idea, expressed in Aristotle's Politics (of which Palla Strozzi possessed a valuable copy), that the good government of'a city was based on the balance of the interests of the social classes (although, Strehlke notes, "the dichotomy between rich and poor in Gentile's painting is more likely a testimony to the artist's skill in conveying inner feelings and emotions"). It is interesting at this point to note that the double Strozzi chapel in Santa Trinita was an ambitious project: "at once a family sepulchre, sacristy, and night choir, it nevertheless represented a work without any precedent" (so Michela Young). In fact, we are talking about a site that was designed not only to celebrate the family, but also as a place open to the city: for some time it was in fact used as the seat of the meetings of the Unicorn banner (one of the districts into which the city was divided at the time), and in Palla Strozzi's intentions it was to be completed with a library open to the public: it would have been the first in Europe. Palla, however, did not succeed, and he finally abandoned the project when, in 1433, he was sentenced to exile, a measure that forced him to leave for Padua without ever returning and that sanctioned the definitive victory of the Medici over the faction led, precisely, by the Strozzi and the Albizi (and it would be Cosimo de' Medici the Elder himself who would open, in the convent of San Marco, the first library in Europe open to the public).

Palla Strozzi did, however, make it in time to see the Deposition installed (the theme had been chosen because of the painting's sepulchral destination), although delivered much later than he must have budgeted: the work had in fact been commissioned from Lorenzo Monaco (evidently, as mentioned, having seen his Annunciation for the Bartolini Salimbeni, Palla must have been particularly impressed), but the Sienese artist did not make it in time to finish the work as he disappeared around 1424. Lorenzo Monaco managed to finish only the predella, the most 'abstract' part, so to speak, of the entire composition, with the Nativity in the center and on either side the stories of St. Onofrio and St. Nicholas, and the cusps, with the episodes following the deposition from the tomb: the Noli me tangere on the left, the Resurrection in the center, and The Pious Women at the Tomb in the right cusp, all painted with the usual elegances that constituted a kind of counterpart in painting to what Lorenzo Ghiberti did in sculpture. The scene in the center was left empty: for its completion, therefore, Beato Angelico had been called in, who was paid in kind for his work, since he received as compensation, Strehlke reconstructed, 27 barrels of wine (about 1,230 liters) delivered to the convent of San Domenico in Fiesole, where the artist lived at the time, as a donation with a value corresponding to the 150 florins that Gentile da Fabriano had received for his own work. We do not know exactly when the commission passed to Angelico: however, it is known from a document that in July 1432 the altarpiece had been placed in the sacristy of the church of Santa Trinita.

As Lorenzo Monaco had done for the Bartolini Salimbeni altarpiece a few years earlier, Beato Angelico painted in the panel for Palla Strozzi a disruptive, innovative scene: the Gospel episode, as in theAnnunciation, occupies all the compartments of the triptych without solution of continuity, and compared to Lorenzo Monaco's work the gold background is also dispensed with, since the scene takes place in the context of a hilly landscape with, in the background, the view of an ideal Jerusalem. The characters, however, are divided into three groups that follow the division of the panel: great emphasis, of course, is given to the central group with the figure of Christ being deposed from the cross, for which, moreover, Fra Angelico studies an entirely new iconography, with the arms that, instead of being attached to the body, are held aloft by the men who are deposing Jesus, so that his figure takes on the appearance of a cross. Beato Angelico also breaks the mold in sketching the expressions of the characters, who abandon any conventionality and are instead caught weeping, suffering, talking, expressing their pain, always, however, with a calmness that conveys that sense of mysticism that is always felt in Beato Angelico's paintings. As early as the 1950s, Frederick Mason Perkins pointed out that the Deposition of Santa Trinita marks "the most decisive moment in Angelico's stylistic evolution, a moment when his 'neo-Gothic' manner is about to be definitively replaced by a style more in keeping with the naturalistically informed ideals of the Florentine 'new school' founded by Masaccio." The work, according to Mason Perkins, also offers us, "more than any other work by its author, a very illuminating insight into the two contradictory sides of the brother-painter's psychological complex: that of a deeply spiritual and imaginative religious man, and that of a born painter, practical and curious, most sensitive to all physical impressions and artistic speculations."

Strehlke also discerned political significance in the Deposition, particularly along the short visual line that links the detail of Magdalene caressing Christ's feet to the footrest where congealed blood is depicted: "During Mass," the scholar wrote, "it is in front of this scene that the priest raises the chalice of wine, declaring 'this is the chalice of my blood [...] poured out as a sacrifice for you.' The attacks of the Hussites and Lollards against the doctrine of transubstantiation-the transformation of consecrated bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ-were the subject of the ecclesiastical council held in Siena in 1423-1424. Angelico and his Angelico and his patrons followed its work closely, as the Florentine Leonardo Dati, master general of the Dominicans, held the position of papal representative. The bloody nails and crown of thorns are shown by the patrician in contemporary garb and radiant halo to a diverse group of people: elderly Jews, a Mongol, a dark-skinned man with his face in his hands, and a young Florentine staring at the cross."

When the work was finished, the altarpiece was therefore placed on the high altar of the chapel of Saints Onofrio and Nicholas. However, Palla Strozzi was only able to see with his own eyes the fruit of his up-to-date patronage for only two years: Cosimo de' Medici, who had been sent into exile in 1433 precisely under pressure from Rinaldo degli Albizzi and Palla Strozzi, who had very strong influence over the city's oligarchic government and had accused his rival of aiming to establish a dictatorship over Florence, took advantage of the fact that a pro-Medicean Priory (the body that held executive power) was installed in the city the following year, and took revenge on his adversaries by sending them in turn into exile (both Rinaldo and Palla would never see Florence again).

As mentioned, the two works that Palla Strozzi had painted for the double family chapel are no longer in Santa Trinita: Gentile da Fabriano'sAdoration of the Magi was removed from its location in 1806, at the time of the Napoleonic suppressions, and four years later it figured in the Gallery of theAccademia, which just in 1810 was being endowed with an important patrimony that included exceptional masterpieces, such as Masaccio and Masolino' sSt. Anne Metterza , Verrocchio ' sBaptism of Christ and Leonardo da Vinci 's The Supper at Emmaus by Pontormo, gathered here to instruct the young students of the Florentine Academy. It was then moved to the Uffizi in 1919, although not whole: the predella compartment with the Presentation in the Temple had been sent to France in 1812, at the time of the Napoleonic spoliations, and was therefore replaced with a copy. The same process also applied to Beato Angelico's Deposition : with the Napoleonic suppressions, the altarpiece was removed from the church and moved to storage, then displayed in the Accademia Gallery and finally, since 1998, kept in the Museo di San Marco.

Palla Strozzi had, however, done so in time to write a fundamental chapter in Renaissance art: for a long time, in the church of Santa Trinita, three crucial and different moments of Florentine art could be seen, which, while sharing the same fifteen-year turn, offered a vivid testimony of the summit of international Gothic, sumptuous and narrative, of Gentile da Fabriano, of the tension of Lorenzo Monaco who sought a mediation between experimental attempts and his intense spiritual and almost abstract refinement, and of the new sensibility of Beato Angelico, made of coherent space, rational light, classical composure, all with a gaze nevertheless turned to tradition, with the figures still able to dialogue with the finesse of a Lorenzo Ghiberti. The coexistence of these works in the same building created a sort of environment of confrontation between the continuity of tradition and the new Renaissance instances of balance, measure, and perspective that were beginning to assert themselves in the religious sphere as well, thanks to the mediation of a refined, modern, up-to-date patron like Palla Strozzi. Add to this the fact that, by virtue of the opening of the Strozzi Chapel to the citizens and the plans that Palla had for the church, Santa Trinita also represented a privileged meeting point between traditional spirituality and the new instances of Florentine Humanism. Santa Trinita was thus a kind of visual laboratory of Florentine taste and humanistic thought: It was certainly not a center of theoretical experimentation, but it was nevertheless a fundamental place of mediation and diffusion of novelties, and perhaps this fundamental role has not been sufficiently emphasized as it has happened with other places in Florence where fundamental pages of the history of art have been written (think of the Brancacci Chapel or even just the convent of San Marco). A key place, then. A place of confrontation, a crossroads whose centrality was reaffirmed by the 2025-2026 exhibition.