It is safe to assume that John Ruskin had not grasped the paradox inherent in the compliment he had intended for Blessed Angelico when he wrote that Fra’ Giovanni da Fiesole formed a class of his own, meaning that “he was not an artist proper, but an inspired saint.” Ruskin, in considering Angelico a saint (and more than a hundred years later would be comforted in his conviction even by John Paul II, who elevated the painter to the rank of the blessed officially recognized and venerated by the Catholic Church), did not realize that he had somehow denied him his stature as an artist, and among the most singular of his time. Of course, it is not possible to fault him for this, either because, throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Angelico would not be able to shake off this aura of inspired mysticism that all exegetes of the time tended to attribute to him (Schlegel said that his art was an act of worship, and that Fra’ Giovanni “had in mind no vain glory or passing effusion, but the edification and joy that the faithful would experience in seeing the objects of their veneration in beautiful form”), and because in all of the Renaissance there was perhaps no painter more counterintuitive than he. Beato Angelico is a contradiction made of light and color. And to some extent Georges Didi-Huberman realized this when, as a young man visiting the Convent of San Marco, he was captivated not so much, and not only, by the figures Angelico had left in the monks’ cells, but rather by the four faux marbles he had painted under the Madonna of the Shadows, spraying paint against the wall as Pollock would do on his canvases half a millennium later. Those colorful patches (“disconcerting,” Didi-Huberman had called them), those startling pieces of abstract painting ahead of the letter, had to make sense, had to have been painted according to a deliberate intention, and Didi-Huberman was trying to’frame them within his theoretical framework on dissimilarity, as a means employed by Angelicus to invite the monks to contemplation and to figure the non-figurable, as a means of overcoming the limitation of narrative representation and allowing the image to convey the sum spiritual truth to the subject. Laurence Gérard-Marchant would later reply to him, challenging several theological smears and, not least, the extraneousness of the Dominicans of the fifteenth century to a form of direct mysticism that would justify the presence of the marbles as facilitators of a process by which the monk would move from the vision of reality to a contemplative experience. Here: the ultimate meaning of these marbles still eludes us. It is one of the many contradictions of Fra Angelico.

Those who visit the major exhibition that Florence is dedicating this year to the Mugello painter, born Guido di Pietro, later to become a friar with the name Giovanni da Fiesole, and then to pass into art history with the name by which he is now known to all (since a few years after his death: it was Fra’ Domenico di Giovanni da Corella, in his poem Theotocon written around 1464, who first called him Angelicus Pictor), should not make the mistake of neglecting the section set up at the Museo di San Marco, although the bulk of the exhibition curated by Carl Brandon Strehlke, with Stefano Casciu and Angelo Tartuferi, is concentrated in the eight rooms of Palazzo Strozzi. It is interesting to note how this splitting reflects, in a way, the two souls of the patronage that always supported Fra Angelico’s work: the religious one on the one hand and the secular one on the other, notably the patronage of Palla Strozzi who, it will be seen when visiting the exhibition, would have contributed in no small way to Fra Giovanni’s fame and success. One should not, it was said, make the mistake of skipping the section at the Museo di San Marco, and if possible one should begin one’s journey from here, and not from Palazzo Strozzi. First of all, because this is where the first chapter of the exhibition is set up, which also coincides with the most interesting and the most dense with novelties of the entire review. And then, because in order to get to the Sala del Beato Angelico, specially rearranged to accommodate the first part of the exhibition, the visitor must pass in front of the Sala del Capitolo, and cannot help but enter it and observe the imposing Crucifixion, the largest, most ambitious fresco that Angelico left in the convent where he worked between 1438 and the end of 1442. Before entering the exhibition, one will have the opportunity to grasp another of Beato Angelico’s contradictions: a forgotten interpreter of his painting, Domenico Tumiati, the author in 1934 of a reconnaissance dense with poetry but also capable of sparkling openings on his painting, had already noticed it. In discussing the Crucifixion, Tumiati could not help but note that “all the faces are drawn from life, the folds are reproduced with every exactitude, light and dark are used to form the relief; but everything lives in a superior world, as if transfigured.” Here, then, is that benevolent sense of estrangement that one feels when looking at almost all of Angelico’s things, strong when one finds oneself inside the Sala del Capitolo, seeing those faces so exact that they seem to be portraits, and yet floating on a sky that moreover today is only a shadow of what it must have been in ancient times, when the original azurite had not yet fallen. And pervasive when one sees much of Beato Angelico’s production all gathered in one place.

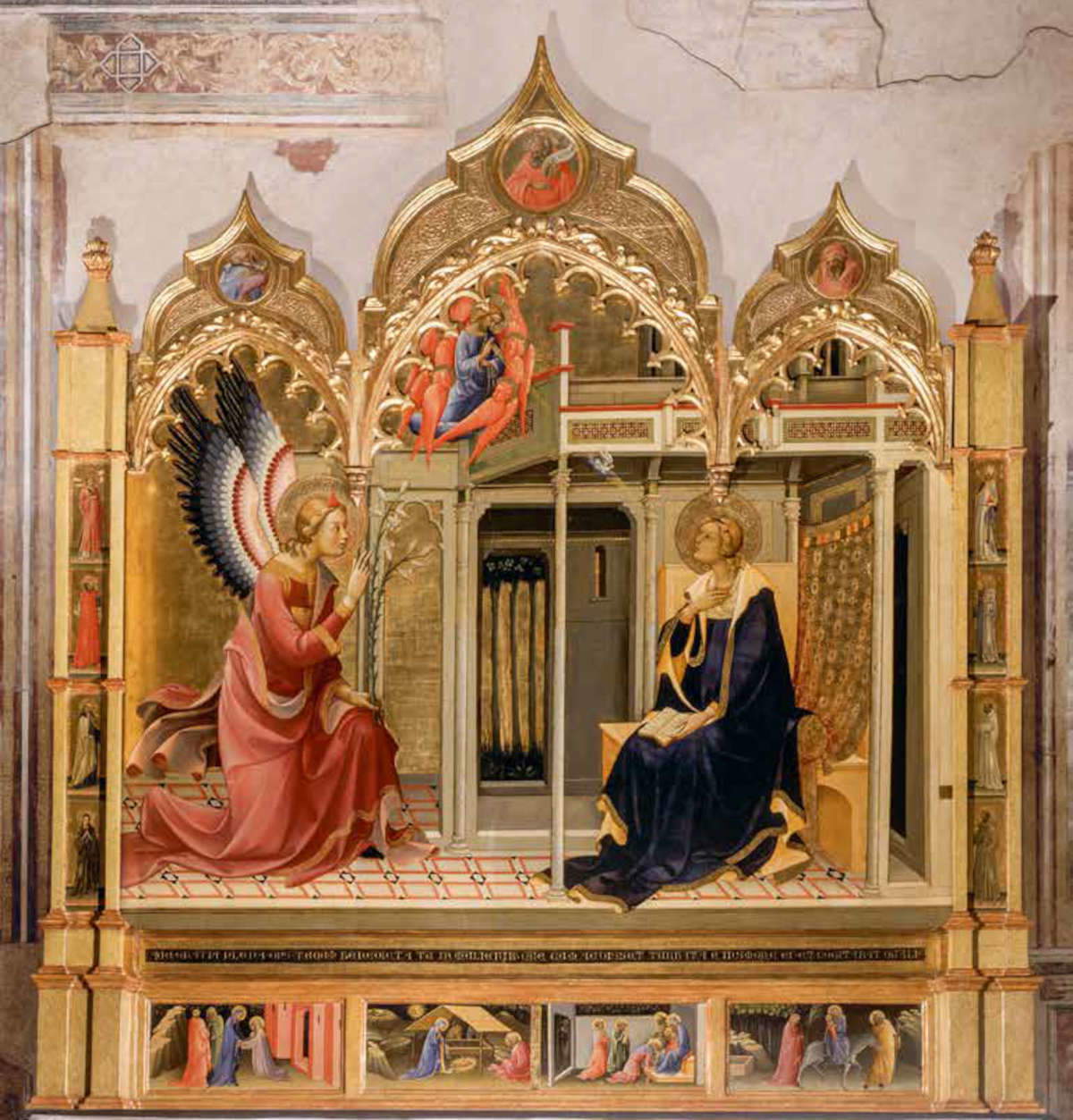

The section set up in the Museo di San Marco, which is actually divided into two parts (the first chapter, on the artist’s beginnings, and then the portion arranged in the Library that probes the production of Angelico the miniaturist), is an excellent introduction that offers an opportunity to understand the origins of the Tuscan painter’s paradoxical universe. More in detail, the first room provides an interesting briefing on the most recent orientations about the early stages of Angelico’s activity, and although some parts of the artist’s “prehistory,” as Angelo Tartuferi calls it, who has Angelo Tartuferi, who has been responsible for arranging what we can still consider the “most controversial period of his activity” (this is, after all, physiological in an exhibition that aims to give an account of an artist’s entire career), the curators have put together a mass of material that is able to provide more than useful coordinates, starting with the spectacular Fiesole Altarpiece that opens the exhibition and which, as we see it today, is the result of an intervention by Lorenzo di Credi who in 1501 modified the original format (a panel shows a graphic reconstruction of what this polyptych must have looked like originally, with its cusped woodwork and subdivision into compartments according to fourteenth-century tradition) and transformed the polyptych into a square panel, with its gold background covered by the classical architecture and airy landscape that we now see behind the saints. Let us not be too misled, then, by what we see on the background: let us concentrate, rather, on the figures of the saints and angels, with those lance-shaped, multicolored, unreal wings of theirs. Here, in his first major public commission, the artist, Tartuferi writes, “explicitly and unequivocally declares the stylistic-cultural components constitutive of his art at that time, traceable to the works of Gherardo Starnina and Masolino da Panicale.” The question of Angelico’s alumnus, who by the time of the Fiesole Altarpiece must have accumulated about ten years of experience, still remains unresolved, between those who believe that Gherardo Starnina must have been his main reference, and those who would have him a pupil of Lorenzo Monaco: judging from what can be seen in the exhibition, it seems that the young Guido di Pietro, when he had not yet taken his vows (he would have entered the convent around 1420), would seem to have leaned more toward Starnina’s delicate softnesses and Masolino’s measured finesse than toward Lorenzo Monaco’s abstract lambicacies, and it would seem to be proved, almost beyondany well-founded doubt, the juxtaposition of the splendid Madonna of Humility lent by the Museo Nazionale di San Matteo in Pisa, an early work, datable to something before 1420, with Masolino’s Madonna of the Milk , from a few years earlier, which instead arrived from the Uffizi and of which Angelico may have given his own inspired interpretation. Useful then is the comparison in the exhibition between the Fiesole Altarpiece and Starnina’s Madonna of Humility on loan from the Museo Diocesano in Milan, with the enthroned Virgin in Angelico’s altarpiece seeming almost an update of the one painted by the artist we may consider his mentor. The figures of the saints, elegantly draped with robes that fall in wide, voluminous and sometimes even calligraphic draperies (look, in the Fiesole Altarpiece, at that of St. Barnabas) then offer a reminder of the sculptures of Lorenzo Ghiberti, another possible reference of the young Guido di Pietro: there are a pair in the exhibition, on loan from the Pinacoteca Comunale di Città di Castello.

Among the early phase works considered cornerstones are the Thebaid, which despite its fame has been definitively cleared by critics only in recent years (since the 1990s, although with some scholars continuing to deny its authorship to Angelico and even its antiquity: instead, Angelico’s authorship is reaffirmed in the exhibition, although it is possible to argue that the panel from the Museo di San Marco represents a hapax in the artist’s career), the Griggs Crucifixion from the Metropolitan Museum, a work dense with references to Masolino and Ghiberti, the very fine Madonna and Child Enthroned and Twelve Angels from the Stäof the Museum which is displayed next to a copy of it executed by Andrea di Giusto (so that anyone can perceive the difference between an excellent artist like Andrea and an outlier like Beato Angelico), and above all the Crucifixion that appeared on the market a few months ago and was purchased for five million pounds for the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford: a work that has long been part of Angelico’s catalog (it was first recognized to him in 1996 by Francis Russell), and a panel among the most exquisite of his early production, it is now on display in Italy for the first time, and its presence constitutes one of the high points of the Florentine exhibition, on a par with the one to which s’immediately following, the extraordinary confrontation between Beato Angelico’s Triptych of St. Peter Martyr , for the first time reunited with its predella, and Masaccio’s Triptych of St. Juvenal , an exceptional loan from the Museum of Sacred Art in Reggello that thus allows two fathers of the Florentine Renaissance to be seen side by side in a vis-à-vis that, however, is not unprecedented: already three years ago, in a fine Uffizi Diffusi exhibition at the Reggello museum, the two works were displayed paired. And if Masaccio was the revolutionary, Blessed Angelico was the first artist to understand the scope of that revolution: the Triptych of St. Peter Martyr is one of the first works to share some of Masaccio’s innovations, although to date it is not known whether Angelico had arrived by independent means to master the depiction of space and volume (especially in the cusp, where he painted the stories of Peter Martyr) or by looking at his colleague’s work. The exhibition espouses the first of the two hypotheses: for Tartuferi it is necessary to highlight the “substantial mental autonomy that transpires from Angelico’s two most ’Masaccesque’ works, which instead of more or less direct derivations from coeval exemplars of the Castel San Giovanni genius s’impose themselves as the result of his autonomous elaboration of a new model of vision, achieved at the fulfillment of a coherent, dazzling evolution that started from a matrix of quite late Gothic origin.”

We leave the Museo di San Marco, after visiting the section set up in the Library and after reviewing the frescoes of the monks’ cells, to head to Palazzo Strozzi, where the curators have embraced the idea of an itinerary that, basically, follows the evolution of Beato Angelico’s painting but is organized by themes, with all the overlaps and anachronisms that such a choice entails and that, in some ways, weigh down the visiting itinerary, particularly if one considers that Beato Angelico’s art often experiences sudden and surprising changes, which would be best followed with an itinerary that is as linear as possible. It cannot even be said that at Palazzo Strozzi the itinerary begins where the one at the Museo di San Marco left off, since in the first room we are immediately projected into the church of Santa Trinita, with one of the most exciting comparisons of theentire exhibition, that between Lorenzo Monaco’s Bartolini Salimbeni Alt arpiece and Beato Angelico’s Strozzi Altarpiece , which in ancient times stood in the same place (and, again, a panel offering a reconstruction of the setting is made available to the public in the exhibition: it should be emphasized that the presence of these graphic apparatuses is one of the most useful and well-conceived elements of the exhibition), with a portion of the predella of Gentile da Fabriano’sAdoration of the Magi evoking the masterpiece by the Marche artist that remains in the Uffizi. The Strozzi Altarpiece was originally commissioned from Lorenzo Monaco, who disappeared, however, before finishing the painting he had been commissioned to paint by Palla Strozzi: the commission passed to Beato Angelico who, in the central panel left empty, painted one of his masterpieces, even inventing an iconographic innovation (Christ’s arms which, instead of hanging downward, are supported at the sides so that the very body of Jesus forms a cross) and, as Gentile da Fabriano had done in theAdoration of the Magi, going beyond the traditional division into compartments to imagine, instead, a single scene, where looks, gestures, even minute details count as much as themain episode, since every single tree, every building in the imaginary Jerusalem that Fra Angelico transfigures into one of the most celebrated landscape pieces of the Renaissance, every face caught in an expression of sorrow or surprise induce the viewer to stop, to be moved, to establish a direct contact not so much with the painting itself, but rather with the sacred mystery being witnessed.

When one moves to the next room, however, it takes an effort of imagination to realize that the Strozzi Altarpiece comes after what one sees here, in the room devoted to the development of the “new language” that was to become widespread in early fifteenth-century Florence. Gathered here are a number of works that Angelico executed in a rather turbulent period of his activity, that moment at the turn of the twenties and thirties of the fifteenth century in which his manner experienced abrupt accelerations, returns to the past, radical openings to the new, sometimes even in the same work, as is the case in the Franciscan Triptych that has been reunited with his predella: the archaisms of the three large compartments coexist with the boldness of the scenes of the predella where, although there is no lack of certain solutions that still look backward (in the scene of the Stigmata of St. Francis, for example, the landscape, with those mountains that, Gozzano would have said, “look like papier-mâché rocks in a schoolboy’s crib,” are reminiscent of Lorenzo Monaco’s formalisms), are distinguished by an attention to spatiality that already foreshadows the later evolution of his art. And again, an altarpiece such as that of theCoronation on loan from the Uffizi, with its riot of saints that seem almost to float in the golden light (it is the last, great Coronation so mystical and glimmering), coexists with the Last Judgment , which can be considered, Strehlke points out, “one of the painter’s first experiments in perspective,” with the succession of empty tombs imposing itself as “an affirmation [...] of the rising of the dead at the end of days,” a “straight line in which all curves cease to exist as an expression of the infinite nature of the divine.” And it is curious, if you will, to include among the paradoxes of Beato Angelico’s art this evident intellectualism, this Albertian squaring functional to emphasize the theological concept and which contributes to dilute the air of a painting that, while sharing the same spiritual universe as the artists who had preceded it, to a certain extent detaches itself from it by offering the viewer the sight of a scene that is anything but terrible. Tumiati had noted this: “Not the Dies irae, the medieval Dies illa, inspired Angelico, but the ideal peace of the Gospel, the day of grace, the kingdom of God in its heavenly expression.”

It is difficult then to think of a Beato Angelico who, in the same turn of years, worked in watertight compartments and did not look around: far from it, his painting in these years shows a porosity that makes it so alive, so fascinating, so open. The large molded Crucifixion that the visitor encounters two rooms ahead, and which is perhaps as much of the Masaccio as Angelico produced in his career, to say, is contemporary with the Last Judgment and the Franciscan Triptych, willing to accept the dating of the Crucifixion to about 1427-1430, and the airy Pala Strozzi is a few years later. And, speaking of dating, the hypothesis of placing the Annalena Altarpiece at 1445 does not seem very convincing, because of its alleged dependence on the St. Mark’s Altarpiece , which is displayed in the same room: the argument is controversial, because indeed the Annalena Altarpiece appears to be of older conception than the large painting completed in 1442 (and which in the exhibition is reunited with almost all the surviving pieces of the predella: only one is missing), with those saints so imbued with Ghibertian monumentality that they are matched in certain things by Angelico in the period between the 1420s and the 1430s, and with the haloes still punched and pierced in the 14th-century style and not yet becoming those gilded rays that, from the Strozzi Altarpiece onward, the painter would never abandon. Nor does the format of the altarpiece seem to be an argument for a later date than 1434, on account of the decree of that year imposing the square form for altars: there is no obstacle that would lead one to think that the format of the Annalena Altarpiece was an earlier choice, adopted regardless of an imposition and which, if anything, might have served as a model. And so perhaps we can continue to assign to the Annalena Altarpiece its status as an intermediate work, painted for the use of a clientele that still appreciated gold backgrounds (hence the ingenious intuition of hanging, complete with realistic hooks, meticulously rendered, the gilded brocade from the niches to simulate the luminosity of fourteenth-century polyptychs), its status as a stage of ’approach along a path that would lead to the first fully Renaissance altarpiece, that of St. Mark, which in the Palazzo Strozzi venue benefits from a curious and delightful comparison with a St. Jerome by Jan van Eyck, demonstrating how theAngelico’s portraiture aptitude had some roots in coeval Flemish art, and with a 14th-century Persian carpet that recalls that of the San Marco Altarpiece and attests to the strong circulation of these artifacts in 15th-century Italy.

Much of the production from the same period has been brought together by sometimes very timely juxtapositions: this is the case of the “holy faces,” an extraordinary sequence, one of the high points of the exhibition, which lines up, next to the Christ as King of Kings from Livorno Cathedral (and which at Palazzo Strozzi can fortunately be seen at close range, something that in the Labronian cathedral is unfortunately not possible because of a location that is not exactly happy, especially considering that the arrangement of Angelico’s Christ is very recent: It dates back to 2006), a series of homologous works, from Dieric Bouts to Benozzo Gozzoli and Benedetto Bonfigli, to show how, on the one hand, Angelic iconography drew on Nordic models, and on the other how it had established a kind of paradigm, an immediate image that had become an instrument of prayer capable of a certain diffusion. A number of important works from the 1930s, beginning with the MontecarloAnnunciation , another exceptional loan, as well as the Cortona Triptych and the Perugia Altarpiece, have instead been brought together in a somewhat interlocutory room devoted to “major commissions,” where the datum that stands out is Angelico’s continual comings and goings on patterns that are now innovative and surprising, as in theAnnunciation of Montecarlo, which, of the three surviving altarpieces on the same theme (the other two, those in the Prado and Cortona, are not in the exhibition), is the most radical, now instead linked to a more traditional taste, as in the Cortona Triptych and the Perugia Altarpiece, which despite being works from the late 1930s linger on rearguard modes that were evidently more congenial to a clientele not exactly up-to-date like the Florentine one. The last two rooms, on the other hand, flow in a more classical fashion, following according to a more stringent chronological order the last stages of Angelico’s activity: here, then, is the period in Rome, where the painter had been called by Pope Eugene IV, who had been fascinated by the frescoes of St. Mark’s (one of the masterpieces of those years, the Triptych of the Last Judgment, stands out in this section, which can be admired together with one of the most refined compositions of the last Angelico, the Madonna and Child with Saints from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which is another reason to see the exhibition, and together with two drawings that came from Harvard’s Fogg Museum that some say represent the only extant evidence of the lost frescoes of Eugene IV’s Chapel of the Sacrament in the Vatican, perhaps a miniature copy of them), and here we have the last Florentine years, where the thirty-two panels of theArmadio degli Argenti, an extraordinary account of the life of Christ with no precedent in painting, the Bosco ai Frati Altarpiece and the experimental Lamentation over the Dead Christ , which, though placed at the close, precedes the other two works by about fifteen years.

It is interesting to recall that Domenico da Corella had referred to Fra’ Giovanni da Fiesole with the epithet angelicus while describing precisely the scenes in theArmadio degli argenti. The adjective by which the artist entered history is thus not to be understood as Vasari understood it, when he said that Friar John was “truly angelicus” since he “spent all the time of his life in the service of God and the good of the world and his neighbor.” that adjective is, in fact, endowed with a far greater theological force, since it was the same appellation given to St. Thomas Aquinas: just as Aquinas was the Doctor Angelicus, Friar John was theAngelicus Pictor, the artist endowed with a superior theological intelligence, proper to a Doctor of the Church (and it is not by chance that he would be given a monumental burial, an honor at the time granted to very few artists). And yet, perhaps any attempt at framing would necessarily reduce part of Angelico’s stature: this is perhaps the most concrete evidence of an exhibition that hides none of the many faces of this painter so changeable, so paradoxical. To say him simply “friar painter” would be a diminutio, for he was not only a devout, simple and pious man, he was not only a man of faith. Similarly, to consider him only by virtue of his adherence to Renaissance principles (indeed: according to Calvesi, Angelico was a promoter of these new values) would obscure his qualities as an extraordinary translator of Thomist doctrine through images: in the catalog, Gerardo De Simone cannot help but note how, for example, the three angels of the Triptych of the Last Judgment, one golden and the others strikingly transparent, reflect the idea, expressed in the Summa theologiae, that “angelic nature is spiritual, ethereal, and in its making itself visible to man appears composed of light or air.”

It is this openness, this comprehensive investigation, this willingness to probe the many aspects of one of the most versatile painters of the Renaissance that is one of the many merits (among which should certainly be mentioned the installations on celestial backdrops, both at Palazzo Strozzi and San Marco, whichenhance the light of Angelico’s works, the excellent lighting, the detailed, meticulous and updated catalog) of a truly extraordinary exhibition: We are talking, after all, about the most complete review ever of Fra Angelico, the fruit of many years of commitment, an exhibition that, exactly seventy years after the first and so far last monograph on him, has been able to bring together the largest amount of autographic material on Fra Angelico. vast amount of autograph material by the great painter (and what is more, with several masterpieces by many comprimarî) in the places closest to him, the convent where he worked for several years and the palace built by the descendants of one of his most illustrious patrons. It is difficult to see anything similar again in the imaginable future.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.