Domenico Beccafumi's cartoons for Siena Cathedral: the idea that anticipates light in marble

Domenico Beccafumi's preparatory cartoons for the floor of the Duomo are preserved in the Pinacoteca di Siena: graphic masterpieces that reveal the invention and craftsmanship behind one of the most original artistic endeavors of the Renaissance.

By Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta | 05/06/2025 18:43

Cesare Brandi, in 1933, compiling the catalog of the collection held by the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena, had called them "heirlooms." a term that has perhaps become inadequate today to define, in a single word, the cartoons that Domenico Beccafumi (Domenico di Jacopo di Pace; Sovicille, c. 1484 - Siena, 1551) executed for the floor of Siena Cathedral, since we are now used to indicate by the term "heirloom" any fetish that belonged to any personality a little better known than the average person. At that time, however, the term "heirloom" was understood to mean an ancient and precious object, worthy of the utmost care: and in this sense Brandi had well grasped the value of Domenico Beccafumi's cartoons, a surprise that the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena reserves for the visitor toward the end of the itinerary, in a room that brings together these pieces that once belonged to Siena's Spannocchi collection and are now instead the patrimony of all. All the more precious because they are the only surviving cartoons from the entire enterprise of the sumptuous marble tale that is the floor of Siena Cathedral.

Beccafumi is the greatest Sienese interpreter of Mannerism: one also goes to the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena to appreciate the juicy, revolutionary fruits of his mind and hand, to observe his best-known works, above all the Trinity, a work of extraordinary modernity that precedes by about ten years the masterpieces we now most commonly associate with Mannerism, those of Pontormo or Rosso Fiorentino. Beccafumi is also the author of the most innovative and singular portion of the floor of the Sienese Cathedral: he made his cartoons between 1524 and 1531, tracing in ink and charcoal, on these large sheets, the graphic conception for the part that fell to him of the centuries-old undertaking of the floor of the Duomo. And today these sheets still bear witness to that direct link between the artist's idea, his elaboration, and the material translation of the finished work: a fragile but living bridge, a bridge between thought and stone. In this case, however, they are not sketches drawn in the early stages: the cartoons are life-size drawings, technical tools that are not, however, lacking in significant artistic value, intended for the master stonemasons who, stepping into the part of patient translators, would give form and light to the marble commesso. This extraordinary decorative system, which covers the floor of Siena Cathedral like an immense carpet of symbols and narratives, constitutes one of the most original undertakings of the Italian Renaissance, and Beccafumi's cartoons are a direct, precious and now extremely rare testimony to it.

In the Renaissance, the use of preparatory cartoon was common practice in large art workshops. But in Beccafumi's case, it could be said that the cartoons are not just working tools: these sheets reveal the intimate creative forge of an artist who did not limit himself to planning but finely controlled every step, from iconographic invention to luministic rendering. The charcoal strokes, ink traces, and accurate details of faces and expressions restore an authentic image of his hand.

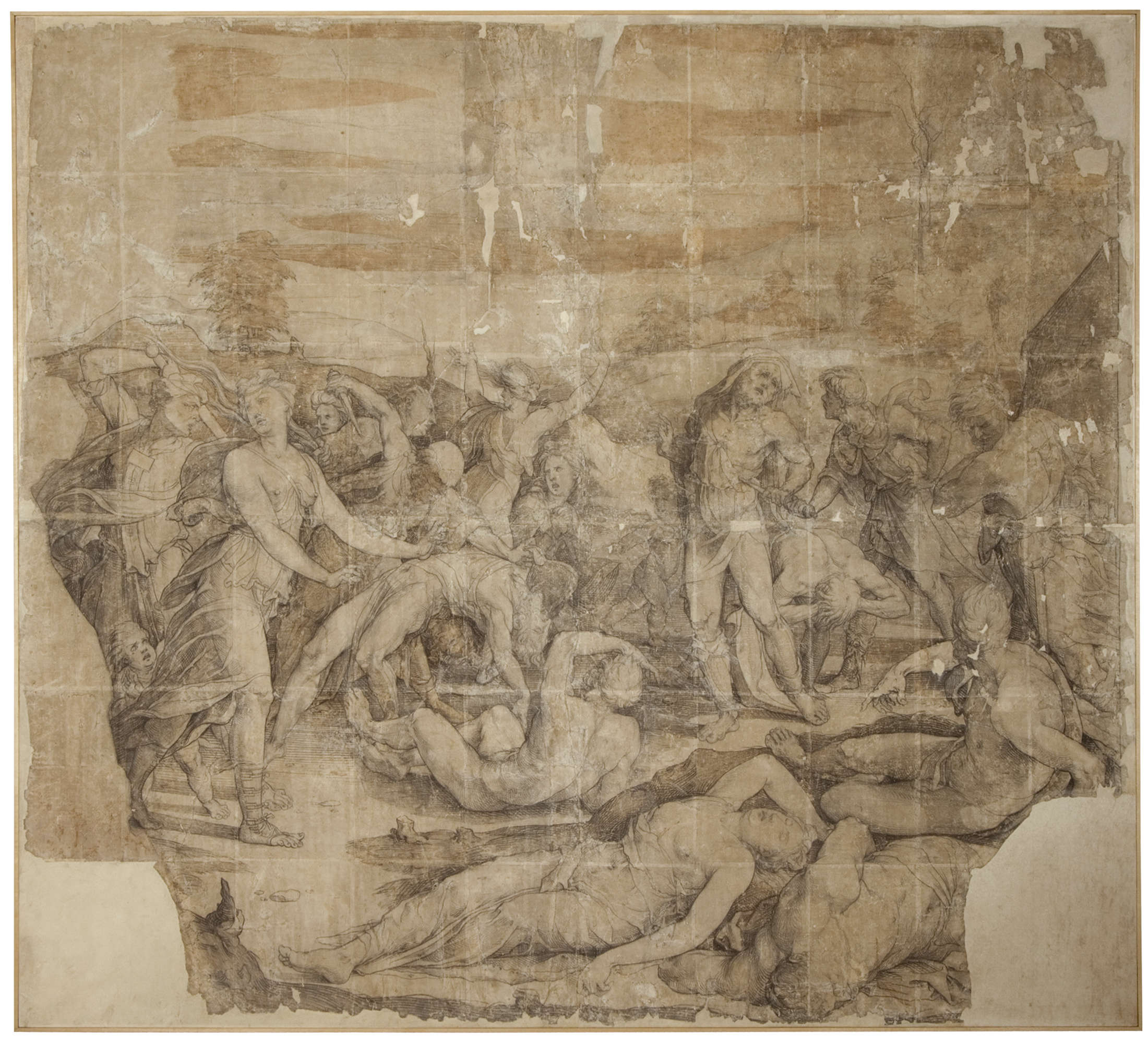

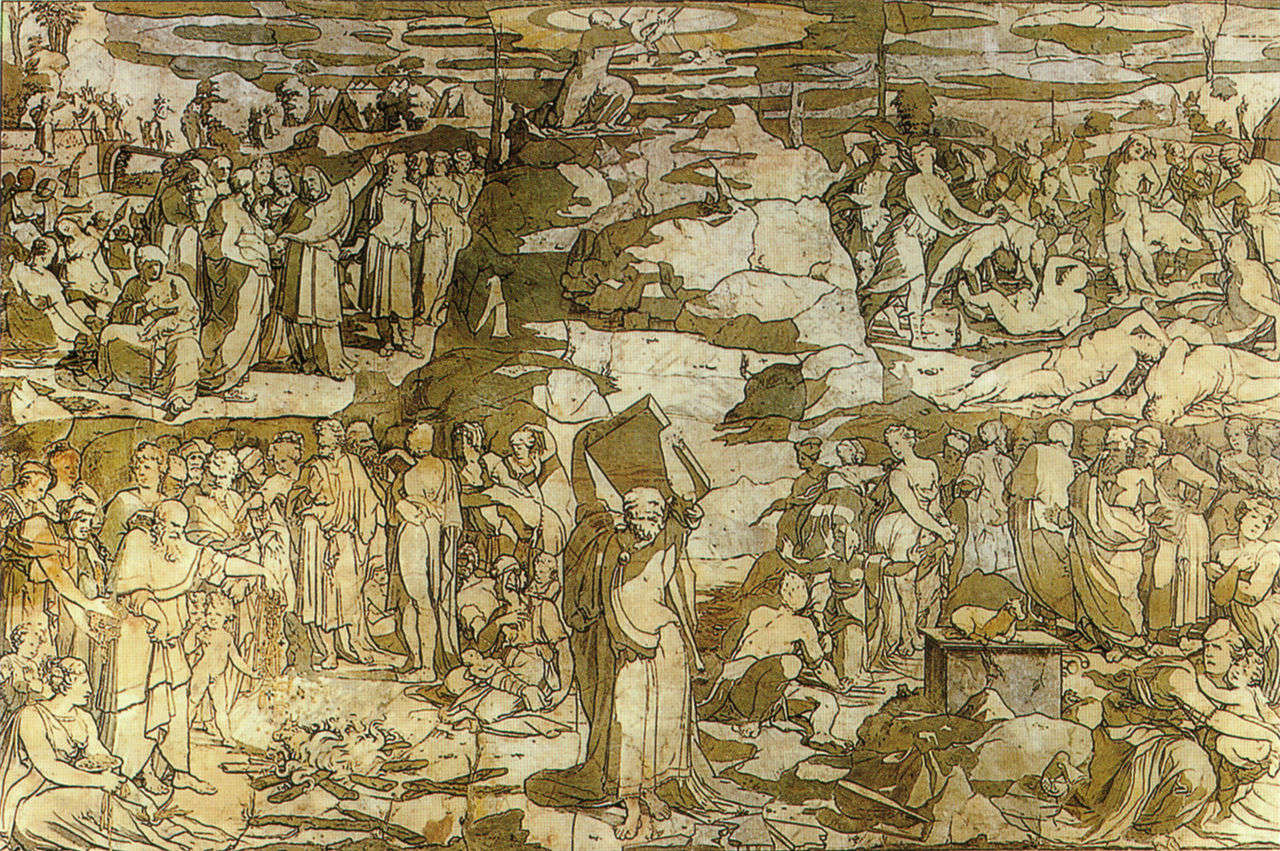

After receiving an initial payment in 1524, Beccafumi began work on the venture in all likelihood the following year. The five works on display at the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena document the large panel with the episodes of Moses on Mount Sinai, placed beyond the central hexagon of the floor in the direction of the high altar. Added to these is the cartoon, not exhibited, for the frieze below, with an episode from the same story(Moses causing water to gush from the rock). A theme taken from the Old Testament, with which the artist staged crucial moments in the history of the Jewish people: Jews waiting for Moses' return from Sinai (the only one of the cartoons exhibited in a separate room), Moses receiving the tablets of the law, again the prophet breaking the tablets of the law, Aaron making the golden calf, the killing of the Jewish worshippers of the golden calf by the Levites. The entire cycle stands as a narrative architecture dense with religious and moral meanings, but also as a masterful essay in formal and technical experimentation.

The artist, in the service of the Opera del Duomo for over thirty years in order to complete this undertaking, was able to reform the aesthetics of the floor with an entirely new sensibility. Taking advantage of the different coloring of the marbles (white, gray, yellow), the artist was able to achieve striking effects of light and shadow, anticipating, in a way, future research on luministic effects in seventeenth-century art. In this context, the cartoons testify to how the visual effect was already thought out in the beginning, with careful graphic design of the relationship between light and dark. This is especially noticeable in the cartoon with Moses receiving the tablets of the law on Sinai, where the light rendering, though barely hinted at by a few means, is already effectively set up.

The frieze then imposed a technical, practical challenge: that of "representing the miracle of water gushing from the rock," scholar Francesca Scialla has written, since Beccafumi would have had to work "around the nature of the surface at hand, a long rectangular strip enclosed between the pillars that connect the space of the dome to the presbytery area." The artist found a particular solution, arranging the figures in rows as if they were in procession, placing Moses in the center, and above all without giving up the individual characterization of the characters, although, in the translation into marble inlays, some of the expressiveness that Beccafumi managed to instill in the characters on the cartoons was necessarily lost. The marbles, however, retain that striking alternation of light and shadow that constitutes perhaps the most arresting element in the stone translation of the cartoons. The effects were able to capture even Giorgio Vasari himself, who in his Lives reserved strong words of praise for Domenico Beccafumi's frieze: "this frieze is so beautiful, that for a thing in this genre it cannot be done with more artifice, since the shadows and the fluttering that these figures have are more marvelous than beautiful. Et ancora that all this work, because of the extravagance of the work, is beautiful, this part is held to be the best and most beautiful."

It was precisely the frieze, according to Francesca Scialla's reconstruction, that engaged Beccafumi in the early stages. The following years up to 1531 were spent on the panel, which began to be translated into marble around 1529: the stonemasons who obtained the commission had to organize the five episodes drawn by Beccafumi in a single panel, on a single surface, placing Mount Sinai in the center and, around it, as if the whole story were to revolve around that mountain which is, moreover, central to the biblical narrative, all the scenes. And indeed the centerpiece of the entire narrative is the whirlwind that appears above Moses, symbolizing divine intervention, the arrival of the Eternal Father who delivers the tablets of the law to the prophet. "The imperative of a comparison between drawings and stone commissions also applies here," Scialla writes, "in order to fully appreciate the invention born of Domenico Beccafumi's imagination, to the advantage of the former where the passage of centuries and the fragility of the support have undermined their legibility."

It has been said that cartoons were primarily technical tools, so their destiny was not to survive. By their very nature as temporary tools, functional for the transposition of the work into marble, they were destined to be thrown away or reused. As chance would have it, however, these sheets were preserved, we do not know why. They were probably seen under the counter (in fact, the Opera del Duomo of Siena would have liked to keep the cartoons for itself) by Giovanni Battista Sozzini, a close collaborator of Beccafumi, and by 1565 they were already in the Spannocchi collection, one of Siena's most prestigious collections. The purchase, attributed to Tiburzio Spannocchi, ensured their preservation in a private setting, safe from dispersion and damage. Over the following centuries, the cartoons were handed down from generation to generation, passing from Palazzo Spannocchi, on Via della Sapienza, to the Piccolomini Spannocchi collection, born in 1774 through the marriage of Caterina Piccolomini di Modanella and Giuseppe Spannocchi. At some point in their history, there was also the interest of the commissioners sent by the King of England, Charles I, to look in Italy for works of art with which to replenish the British collections: this at least according to what a Dominican friar, Isidoro Ugurgieri Azzolini, recounted in 1649. The commissioners, according to the account, offered Pandolfo Spannocchi, Tiburzio's nephew, an astronomical sum to get possession of those sheets: Pandolfo refused, saying that he thought he was richer and wealthier by keeping Beccafumi's cartoons in his house, than by adding to his possessions the five thousand scudi that the English commissioners had offered him.

Moved in 1825 to the church of San Domenico, where they were hospitalized probably to redeem them from their poor state of preservation, and later to the Institute of Fine Arts, they officially entered the civic heritage of the city of Siena in 1835. Today the cartoons are on display in a room specially designed for their conservation and enhancement, after there was perhaps even a risk of losing this heritage in the past. The fragility of the paper on which Beccafumi had worked, composed of several sheets juxtaposed to achieve the large formats required, has imposed several restorations over time, necessary to preserve them: the first dates back to 1939, but the most substantial were carried out between the 1970s and 1980s by the Central Institute for Restoration and the Institute of Book Pathology in Rome. Other restorations date instead to 1990. Nevertheless, this same delicacy contributes to the work's charm: every mark, every imprint of the artist, appears sharp, human, close.

The cartoons on display today allow a direct comparison with Beccafumi's other works in the Pinacoteca. It is evident how the artist, while immersed in the climate of Mannerism, follows an original trajectory. His stroke is nervous, theatrical, dynamic, virtuoso, moved. Suggestions drawn from ancient art and the great Florentine masters merge with a personal quest that aims at dynamism, light, and expressiveness. In this sense, the cartoon is not just a sketch or a tool, but a space of invention and freedom. In the room that preserves the cartoons, visitors will be able to catch in Domenico Beccafumi's sheets what cannot be seen in the marble: a detail of Moses' face, a dramatic fold of his cloak, the intensity of a gaze. Where the floor tells with stone, the cardboard tells with sign. This is perhaps the most interesting feature of the long-distance dialogue between the two works, between cardboard and marble, between conception and execution.

The survival of Beccafumi's cartoons, it should be added, is not a simple historical fact. We can think of it, rather, as a living memory of artistic making, an open window on the complexity and grandeur of a collective enterprise that marked the history of Sienese art and to which Beccafumi's cartoons are precious witnesses, the only document of an elaborative phase of that incredible marble inlay floor. Today, in the silent half-light of the room, one of the most evocative halls of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Siena, that ancient gesture, the gesture of the hand that slides the charcoal on the paper, invites everyone to grasp the beauty in the design, to discover the intelligence of one of the most original and happy hands of the sixteenth century, to discover the power of drawing as an idea that takes shape.