It is a different Siena, that of Domenico Beccafumi. It is not the international and embattled Siena of the fourteenth century, the elegant and flowery Siena of the gilded painters from Guido and Duccio onward, the Siena that achieved that unrepeatable and very brief “quarter of an hour of power, wealth and glory,” as the eccentric Robert Douglas called it in his History of the Republic of Siena. If we wanted to play a game and find a topographical counterpart to Beccafumi’s paintings, then his Siena would not be the busy and noisy one of Piazza del Campo, the Banchi di Sopra e di Sotto. It is not the Siena of the sunlit streets, beaten in summer by thousands of tourists. Domenico Beccafumi’s Siena is something else entirely: it is, meanwhile, a more provincial, resigned reality, in steep decline, now without political clout, in economic crisis, destined to lose its independence. It is a city that stubbornly keeps its cultural scene alive, and succeeds in doing so (think only of the wonders of Sodom), even if the larger and more remarkable events now take course far from here. It is a city where the echoes of the wars of Italy resound and which under Pandolfo Petrucci, between the fall of the fifteenth century and the first glimpse of the following century, still manages to live on in some splendor. Those who want to find in the city the atmospheres of Domenico Beccafumi go to Siena in the winter and slip into some shady and desolate alley, where the light even at noon comes in reflections, wander the lonely streets of the less frequented districts, enter some gloomy and deserted church or some museum unencumbered with visitors. We might think that it is here that hovers the shy, solitary, introverted, humble, distrustful and peasant character of Beccafumi, an artist far from everything and everyone, who always remained in his city and only rarely and briefly strayed away, to Florence or Rome.

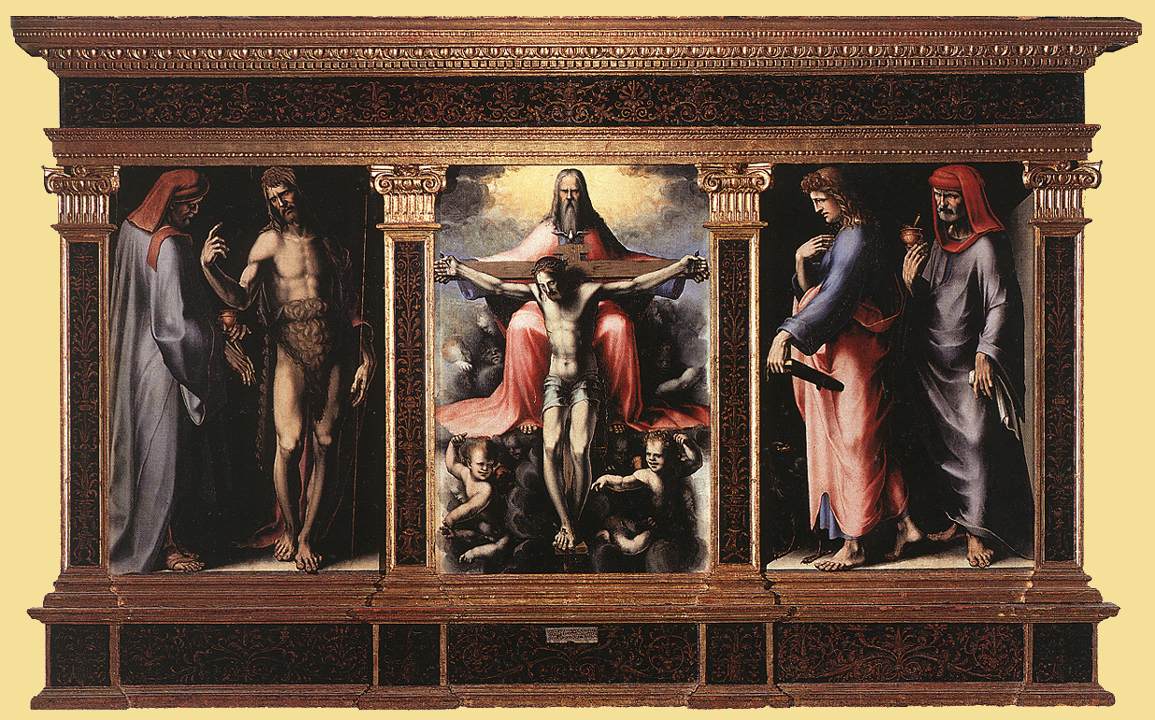

It is a character that emerges from the very beginning, even from his earliest works: his very personal way to the manner already illuminates the stunning Triptych of the Trinity, which until a few years ago was thought to be Domenico Beccafumi’s first known work (recent research, however, allowed the discovery of works that certainly precede it). Mecherino, the son of peasants from the plain of Montaperti, was only twenty-seven years old when in 1513 he was commissioned to paint the triptych by that Battista d’Antonio da Ceva, clerk of theOspedale di Santa Maria della Scala in Siena, recalled in the small cartouche below the central compartment, hanging over the candelabra and grotesque friezes that alone would be enough to reveal the artist’s original personality. The creation of the triptych, however, was part of a larger undertaking, when Domenico Beccafumi returned from his stay in Rome in 1510 or 1511 and the Ospedale di Santa Maria della Scala involved him in the fresco decoration of the Cappella del Manto, where the triptych that is now instead in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena was also located in ancient times.

In the center of the complex is the depiction of the Trinity according to an iconography that is indeed quite usual: Christ on the cross, the Eternal Father behind him, and the dove of the Holy Spirit spreading its wings beneath the face of the deity. On either side are the two compartments with St. Cosmas and St. John the Baptist on the left and St. John the Evangelist and St. Damian on the right. The whole mounted in a square carpentry, with pilasters surmounted by Corinthian capitals supporting a continuous entablature, with gilded corbel. Impossible not to linger on the frieze that decorates the structure, and which reflects what Beccafumi had observed in Rome: however, wrote Alessandro Angelini, “the characters of these fleshy grotesques and detected with strokes of the brush [...] remain then more and more capricious and personal, marked by an inspiration and a bizarreness that already marks Domenico’s culture in Siena here.”

Beccafumi’s is a kind of Mannerism that began even before Mannerism really began: his triptych precedes the Depositions of Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino by about ten years. For Giuliano Briganti, Beccafumi was “an independent of the manner”: the great scholar had placed him in a triad of innovators alongside Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. And in any case, his response to the art of Raphael and Michelangelo was always going to be different from that of his two Florentine counterparts: there are not, in Mecherino’s art, the hallucinated alienations of Pontormo, nor do we glimpse in it the almost blasphemous obsessions of Rosso.

Domenico Beccafumi’s restlessness is of a different sign. When the artist returned to Siena after his stay in Rome, Michelangelo had not yet unveiled the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, while Raphael was preparing to finish the Loggia di Galatea and the Stanza della Segnatura. He had thus painted his Triptych of the Trinity without having seen the great modern masterpieces of the two greatest artists active in Rome.Angelini suggests that the young Sienese may have been more impressed by the works of Bramantino and Pedro Fernández de Murcia that he had been able to see in Rome, and which would have pushed him toward novel solutions. Such as those adopted for the figures, starting with the saints who stand out against the dark background, with their elongated proportions almost like a late Gothic revival , the livid tones that darken the figures of the two medical saints, namely Cosmas and Damian, on the sides, and again the thin, metallic draperies, the coruscating, almost grim profiles. Then, in the center, here is the Trinity ripping through the leaden sky: but it is not an apparition we perceive as serene, cheerful. It is disturbing: God watches us with an almost menacing expression, seated before his bloodless son, like a hieratic deity, gloomy and distant. The angels have almost devilish expressions, and unsettling bordering on the horrifying are those in the clouds that pop up behind God’s legs, with the two supporting him under their feet that seem almost grotesquely burdened by the weight they must bear with their heads. Revealing, at the compositional level, similarities with the Florentine models of Fra’ Bartolomeo and Mariotto Albertinelli, Angelini could not help but notice how the triptych’s central scene is charged with “a spirited and feverish atmosphere, emphasized by the acid tones of the color and the bewitched expressions of the little angels suspended in the clouds.”

When Mecherino delivered the polyptych, Pandolfo Petrucci had been gone for a year, Siena was still living in a happy season if far from its fourteenth-century glories, and perhaps no one would have imagined that it would soon lose its centuries-old independence. It is true: already the aforementioned Briganti, introducing Beccafumi’sComplete Works published by Rizzoli, warned that, throughout the great artist’s career, the city’s gloomy atmosphere might have influenced his story, but to explain an artist’s creativity such determinism is valid up to a point, since the reasons for creation are deeper and often elude documents. Let alone suggestions. “It is not enough to know the sequence of collective events,” Briganti warned, “in order to deduce from them, without any other aid and by fatally bringing them back to present-day experiences, the reactions that they ’then’ provoked on individuals whose biological time of existence if not in whole at least in part, and to a great extent, eludes the formal laws that govern historical time.” It can be said, however, that with his Triptych, so imbued with “mannerist spirit,” to use an expression of Donato Sanminiatelli, one of the earliest scholars of Domenico Beccafumi, the Sienese painter inaugurated de facto a new season. If what Marshall McLuhan said is true, that the artist is a human being who lives the future in the present, then the Triptych of the Trinity can be said to be a work that well supports this idea.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.