by Francesca Interguglielmi, published on 07/09/2020

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

The floor of Siena Cathedral is one of the most extraordinary works of the Renaissance: a true tale of marble (but not only) that unfolds at the feet of those who enter Siena Cathedral.

Upon entering the Cathedral of Siena, dedicated to the Virgin of the Assumption, which with its Gothic forms rises majestically over the acropolis of the Tuscan city, one’s gaze must be directed three hundred and sixty degrees, for one can observe masterpieces of art not only all around us, but also underfoot. Indeed, in the religious heart of this city lies what Vasari called “the most beautiful...great and magnificent floor that had ever been made.” Today, some sections of the floor of Siena Cathedral are only revealed at certain times, while they are usually covered to make the surface walkable, allowing for proper preservation. It lasted for six centuries, from the 14th until the 19th century, and great names in Sienese art worked on it, providing the designs. The main technique employed, along with that of graffito, is that of marble commesso: marble (or semiprecious stones) of different hues is cut and juxtaposed to make the composition.

Already in the cathedral forecourt, at the three portals, there are representations of three priestly ordinations, the result of a 19th-century intervention, which have the task of pulling toward the entrance to the sacred place.

Entering through the central portal, one comes across the admonition “castissimum virginis templum caste memento ingredi” (“Remember to enter chastely the most chaste temple of the Virgin”). The panel above features a depiction of the sage of antiquity Hermes Mercury Trismegistus, made in the 1680s to a design by Giovanni di Stefano (Siena, c. 1443 - 1506), son of Stefano di Giovanni known as Sassetta (Cortona?, c. 1400 - Siena, 1450). This ancient figure, rediscovered in Renaissance times, was the one who delivered the letters and laws to the people of Egypt (as engraved in the book he holds in his hands). The inscription accompanying this panel not only identifies Hermes Trismegistus but also records him as a contemporary of Moses. The literary reference is the Divine Institutions of Lactantius (3rd-4th centuries), in which it is argued how Hermes, and other figures of antiquity such as Orpheus, the Sibyls, Socrates, and Plato, would have intuited the Truth, but without attaining it. In this view, between the ancient pagan world and the revealed Christian world, there would be continuity, as can be seen on the floor of Siena Cathedral. Indeed, continuing down the aisles, one encounters representations of the Sibyls, female prophetic figures of the ancient world in whom Christian culture recognized the revelation of Christ and his message of salvation. There are ten of them (five per aisle), as set by Varro (Rieti, 116 B.C. - Rome, 27 B.C.).

|

| The floor of Siena Cathedral. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| The floor of the Cathedral of Siena. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| The floor of the Cathedral of Siena. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| The admonition |

|

| Giovanni Paciarelli, Plan of the floor of the Cathedral of Siena (1884) |

|

| View of the Cathedral of Siena |

Their names are indicative of their geographical origin: the Persica,Ellespontica,Eritrea, Phrygia, Samia, and Delphica represent eastern and Greek territory; the Libica is from Africa; and the Cumea, Cumana, and Tiburtina indicate the West (specifically, Italy). They were made by different Sienese artists between 1482 and 1483. Each sibyl, worked in white marble (except the Libyan one, for whose complexion a dark type was employed), is depicted against a black background and rests on a brick-colored top. Each is accompanied by two quotations: one allowing their unambiguous identification, the other containing their prophecy about Christ. The symbols that appear next to these women also relate to their revelations. Entering through the portal on the right side of the facade, the first sibyl depicted is the Delphic one, whose design is attributed to Giovanni di Stefano or Antonio Federighi (Siena, 1420/25 - 1490) and redone due to deterioration in 1866-69. Its prophecy concerns the divine nature of Christ.

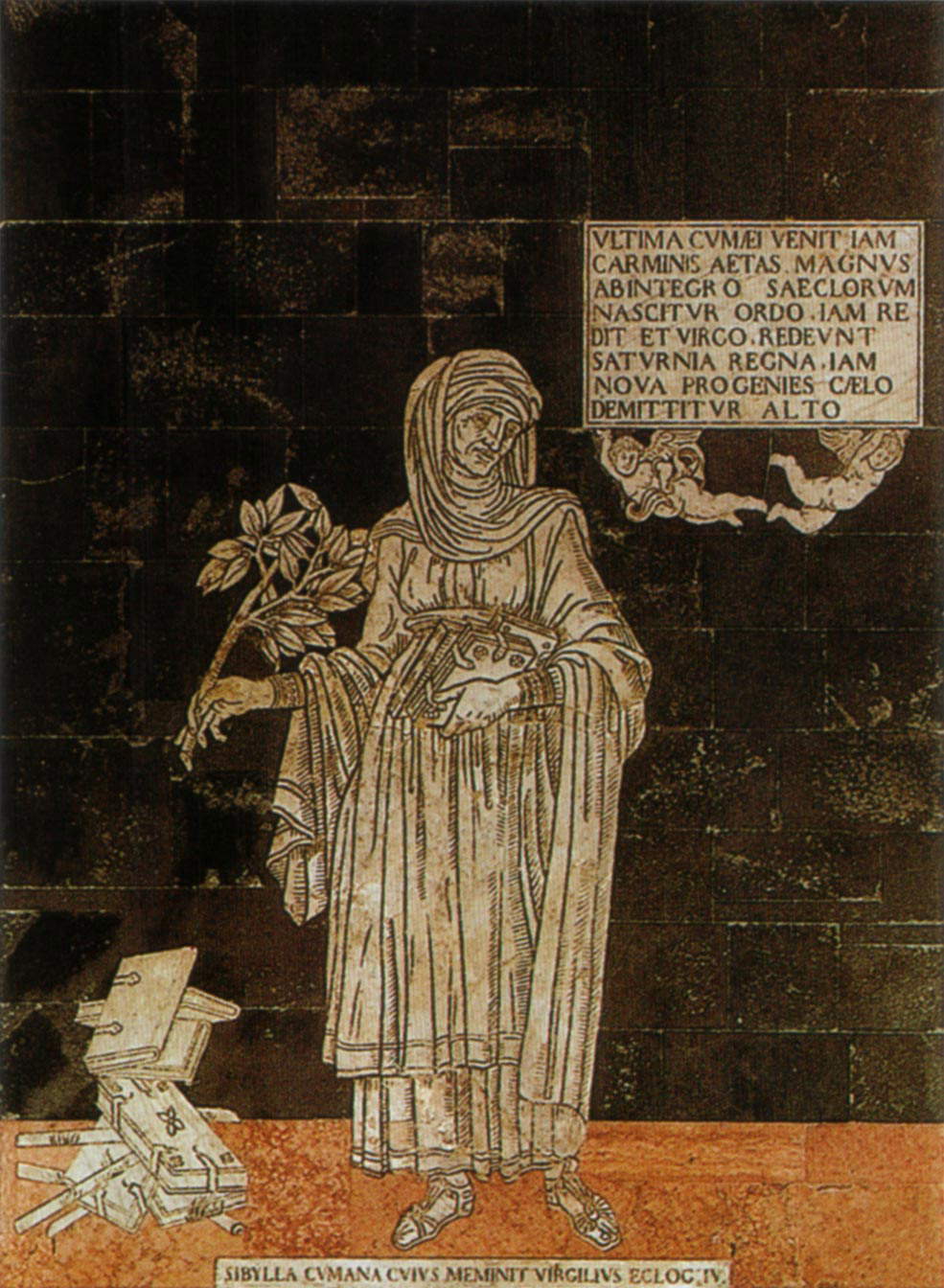

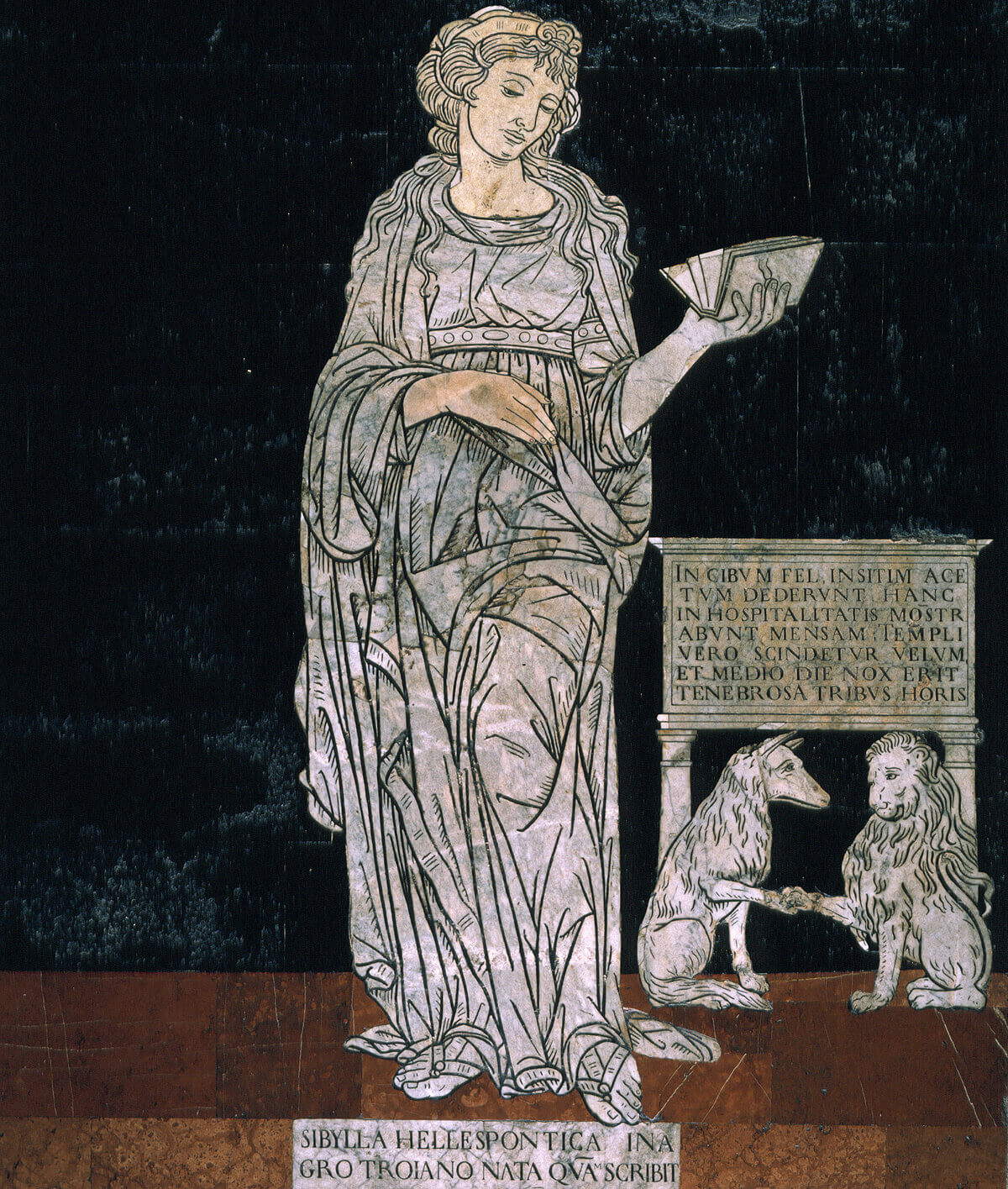

Next we encounter the Sibyl Cumea, presumably attributable to Giovanni di Stefano: the accompanying inscription refers to the resurrection of Christ. Also attributed to the same artist is the Virgilian Sibyl Cumana, who prophesied the arrival of Jesus. The fourth prophetess is the Eritrean prophetess, drawn by Federighi (but again later remakes should be noted). The inscription affixed to her book concerns the birth of Christ. Concluding the series in the right aisle is the Persian Sibyl, attributed to Benvenuto di Giovanni (1436-1509): her prophecy concerns the miracle of the loaves and fishes. Entering through the door on the left side of the facade, the first figure one encounters is the Libyan sibyl, attributed to Guidoccio Cozzarelli (Sienam, 1450 - 1517), who prophesied the scourging of Christ. The next figure, the Ellespontica sibyl, reveals the authorship of the design by Neroccio di Bartolomeo Landi (Siena, 1447 - 1500) and bears as vaticinium the final moments of Jesus’ passion and death. The Phrygian sibyl is attributed, although some uncertainty remains, to Benvenuto di Giovanni (Siena, 1436 - 1509/1518): in the book it holds, the unity of divinity is alluded to, while in the inscription the reference is to the final judgment. Concluding the series are the Samia sibyl, by Matteo di Giovanni (Borgo Sansepolcro, 1430 - Siena, 1495) and the Tiburtine sibyl, related to Benvenuto di Giovanni, bearers respectively of Jewish skepticism in recognizing Christ as messiah and the announcement of his birth.

|

| Giovanni di Stefano, Hermes Trismegistus |

|

| Guidoccio Cozzarelli (attributed), Libyan Sibyl. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| Giovanni di Stefano, Sibilla cumea. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| Giovanni di Stefano, Sibilla cumana. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| Benvenuto di Giovanni, Sibilla tiburtina. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| Matteo di Giovanni, Sibilla samia. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

|

| Neroccio di Bartolomeo Landi, Sibilla ellespontica. © Opera della Metropolitana di Siena |

Returning to the nave, the panel following Hermes Trismegistus depicts the She-wolf suckling twins. Despite the inscription Sena, which leads one to think that the twins depicted are Ascanio and Senio, the legendary founder of the city, it has been observed that the fig tree is associated rather with the myth of Romulus and Remus. Around them, inserted in other smaller circles, are represented the animals symbolizing the most important cities of the Tuscan territory and central Italy: the horse (Arezzo), the lion (Florence), the panther (Lucca), the hare (Pisa), the unicorn (Viterbo), the stork (Perugia), the elephant (Rome), and the goose (Orvieto). In the corners of the frame, there are four other animals: the lion with lilies (Massa Marittima), the eagle (Volterra), the dragon (the dragon), and the griffin (Grosseto). From the point of view of technique, this is the only place where the mosaic technique was used. The present depiction in the cathedral is from 1865 by Leopoldo Maccari, while some fragments of the original composition dating back to 1372 are preserved in the nearby Museo dell’Opera del Duomo.

In the next panel, also the result of a 19th-century makeover but conceived around 1373, there is a reproduction of a large cathedral rose window with an imperial eagle in the center, a symbol of continuity with Rome. The eagle is also a symbol of therisen Christ .

The fourth scene in the central band is one of the most interesting and well-known of the entire cycle: theAllegory of the Mount of Wisdom, dated 1505. It was commissioned from Bernardino di Betto Betti known as Pinturicchio (Perugia, c. 1452 - Siena, 1513), the only non-Sienese artist to be involved in this undertaking, probably because he was already engaged, also inside the cathedral, in the decoration of the Piccolomini Library. A group of sages is climbing to the top of the hill, where Wisdom is located, depicted with a palm and a book in her hands. The sages have come all the way to that island led by Fortune, depicted as a naked maiden holding a sail with one hand and a cornucopia with the other, while with one foot resting on a sphere and with the other on a boat with a broken mast, conveying a certain feeling of instability. On either side of Wisdom are Socrates, who is offered the palm tree, and Cratetes, who empties a basket of precious objects into the sea, thus renouncing the ephemeral things of life, and who is offered a book. The road to Wisdom is not an easy one, but once reached, serenity awaits, symbolized by the plateau.

|

| Leopoldo Maccari, The She-Wolf of Siena (1865) |

|

| Unknown, The Imperial Eagle |

|

| Pinturicchio, Allegory of the Hill of Wisdom |

|

| Detail of the figure of Fortune |

The fifth and final section, involves the depiction of the Wheel of Fortune, a symbol of human affairs. It is depicted with a king seated on a throne at the top of the wheel: three tall figures hang from it. The four figures take on the meaning of Reign , Regnavi, Sum sine regno, Regnabo (derived from Carmina Burana) At the corners of the panel within mixtilinear hexagons are inserted Epictetus, Aristotle, Euripides and Seneca bearing cartouches with inscriptions concerning fortune. It is the result of a 19th-century remake by Leopoldo Maccari based on a design by Luigi Mussini (Berlin, 1813 - Siena, 1888), while the original dates from 1373.

In the transept area one no longer finds depictions that draw inspiration from the classical world, but moves on to the events of the Jewish people, and in some cases there are references to events in recent Sienese history. Moreover, the depictions become more complex, true narrative scenes.

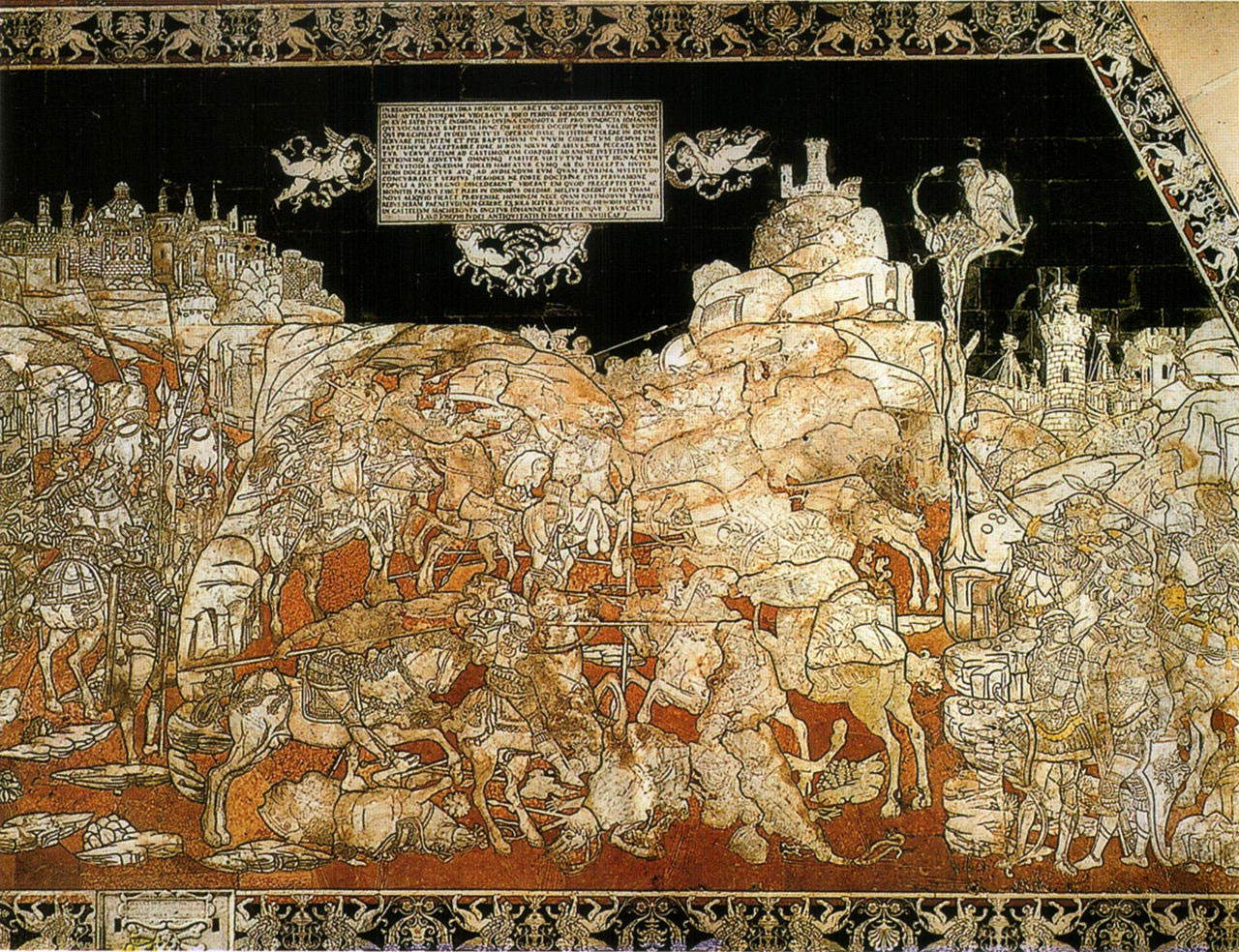

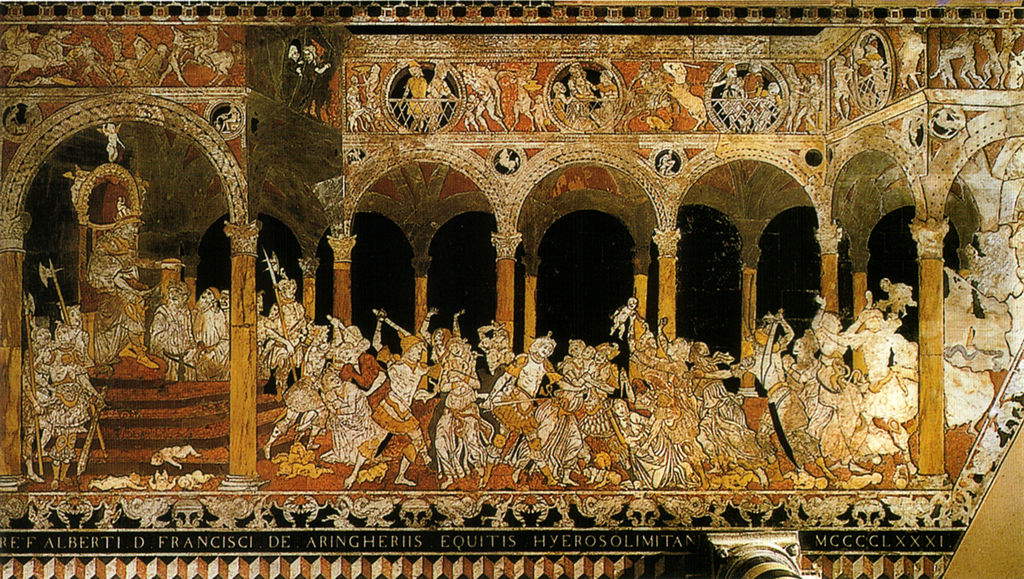

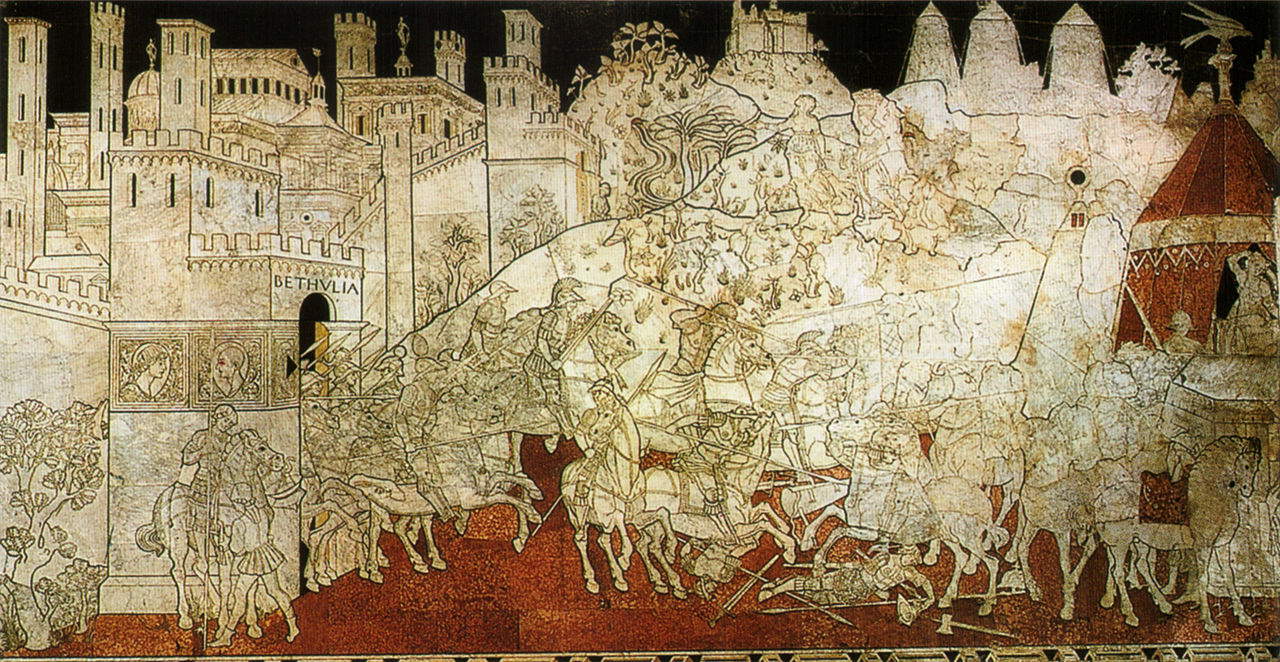

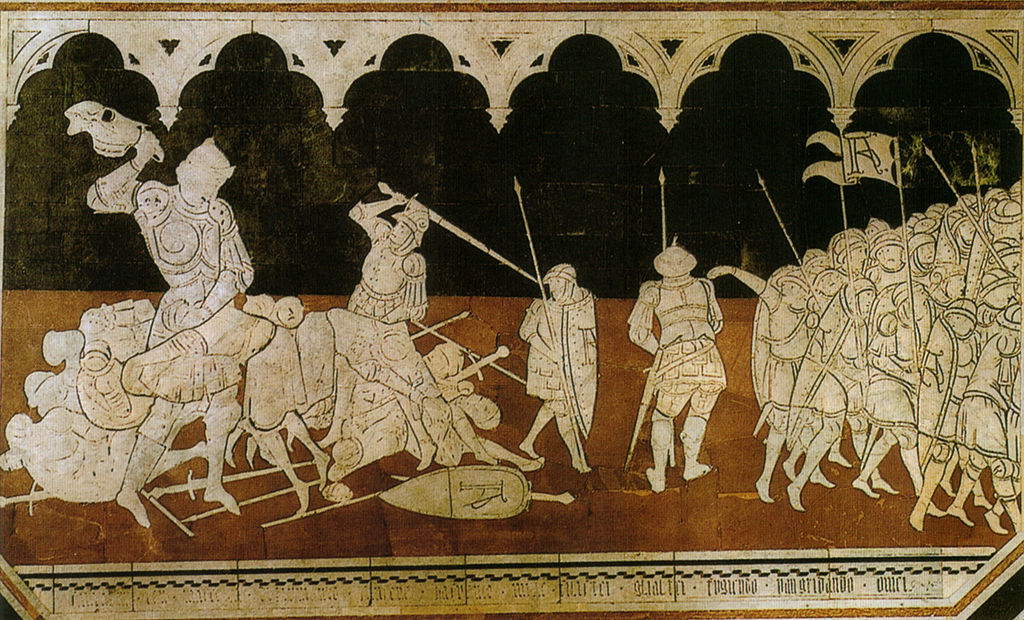

Starting from the lower section of the left transept, the first scene is Benvenuto di Giovanni’s Expulsion of Herod, painted between 1483 and 1485. The story is told in Josephus Flavius’ Jewish Antiquities. The defeat of Herod Antipas at the hands of his father-in-law Areta, king of Arabia, is seen as divine punishment for the killing of the Baptist, of which Herod was guilty. Continuing upward we encounter the Massacre of the Innocents, recounted in Matthew’s Gospel: Herod the Great, father of the namesake in the previous frame, ordered all children under the age of two to be killed. The task of depicting that horror was entrusted to Matteo di Giovanni and carried out in 1481 (the scene was restored in 1790). It is an extremely concise composition with a strong dramatic charge. The choice of this subject has also been interpreted as a reference to an episode in contemporary history: the massacre carried out by the Turks in 1480 after they had conquered Otranto, which deeply disturbed the world of Christendom. Following this, one encounters the Story of Judith, the biblical heroine who freed her city and her people from the siege of Holofernes, holding firm to her faith in the Lord. Within the same frame different moments of the story are depicted. After several names, today the attribution is leaning toward that of Francesco di Giorgio Martini (Siena, 1439 -1501), and again it was restored in 1790.

|

| Leopoldo Maccari, The Wheel of Fortune (1865) |

|

| Benvenuto di Giovanni, The Expulsion of Herod |

|

| Matteo di Giovanni, Massacre of the Innocents |

|

| Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Story of Judith |

Moving toward the chancel area, one encounters the stories dedicated to the rulers of the Jewish people, accompanied by the figures of the virtues. Between the figures of Solomon and Joshua, the biblical episode of Joshua defeating the Amorites is depicted, attributed not without problems, given the state of consumption, to Sassetta. In the area immediately below the high altar, there are three panels dealing with David: David the slinger, David the psalmist, and finally Goliath the stricken. Around it, a frieze with children stretches out. These figures were also retouched in 1777. On the right, within the two figures of Moses and Judas Maccabaeus, the scene of Samson felling the Philistines with a donkey’s jaw by Sassetta continues. Samson, because of his wife, caused the Philistines to lose their grain crop. The Jews, out of fear, handed Samson over to the enemies. He, as soon as he saw them, was pervaded by the Spirit of the Lord, broke free and hurled himself at them, specifically striking them with a donkey’s jaw. Again Samson, who fights inspired by the Lord, is seen as a prefiguration of Christ.

Around the altar, within four roundels, the cardinal virtues are depicted: Fortitude, Justice, Prudence and Temperance along with Mercy.

In the right transept area, except for the Story of Jephthah and the Death of Absalom, no other biblical depictions are found. In front of the Vow Chapel a peculiar composition of six hexagons with a lozenge in the center accommodates the depiction of the Seven Ages of Man (Childhood, Childhood, Adolescence, Youth, Manhood, Old Age, Decrepitude). This is a typical recurring theme in medieval culture, linked to the number seven, which indicates cosmic perfection. Although they were entirely redone between 1869 and 1878 by Leopoldo Maccari and Giuseppe Radicchi on a cartoon by Alessandro Franchi, the conception can be traced back to Antonio Federighi around 1475-1476 (some fragments are preserved in the museum of the work). Continuing to the Chapel of the Vow, there are allegorical figures of Religion and Theological Virtues, executed in 1789 and replaced as early as 1870 with an intervention by Alessandro Franchi. In the upper area, The Emperor Sigismund III of Luxembourg with his ministers is depicted. Domenico di Bartolo (Asciano, 1400 - Siena, 1445) was paid for this scene. It is the only panel on the floor to depict a personage of the contemporary age. He stayed in Siena for 10 months between 1432 and 1433. According to Friedrich Ohly, the Sienese wanted to place the figure of Sigismund among the liberation struggles of the Old Testament, hoping to obtain his help in the current clashes with Florence. Continuing to the right, we encounter the episode of the Death of Absalom, painted by Pietro di Tommaso del Minella (Siena, 1391 - 1458) in 1447. Absalon was David’s favorite son and enjoyed the sympathy of the people. Therefore he organized a plot against his father. David defeated him in the forest of Ephraim. The son tried to escape, but got his hair caught in the branches of a tree, and one of David’s generals struck him down, contravening royal instructions. The episode is related to Judas’ betrayal of Jesus. The subsequent marble clerestory tells the Story of Jephthah, and the conception has been juxtaposed with the names of Neroccio di Bartolomeo Landi and Francesco di Giorgio Martini. Leading the army in the battle between Israel and the Ammonites, he vowed to God that he would sacrifice the first person he met upon returning home, who turned out to be his daughter. Jephthah is seen in parallelism with Christ: just as Jephthah liberates his people and sacrifices his daughter, Christ liberates from sin by sacrificing himself. Compositionally, again different sequences of the story are told within the same space.

|

| Pietro di Tommaso del Minella, Death of Absalon |

|

| Neroccio di Bartolomeo, Story of Jephthah |

|

| Sassetta, Samson Strikes Down the Philistines |

|

| Domenico di Niccolò dei Cori, David the Psalmist |

|

| Antonio Federighi, The Seven Ages of Man |

|

| Domenico Beccafumi, Covenant between Elijah and Ahab |

|

| Domenico Beccafumi, Moses on Sinai |

In the area below the dome, the depiction is organized in hexagons to form a larger one. This section (and those near the high altar) are characterized by the intervention of one of the most important artists of the sixteenth century in Siena, Domenico Beccafumi (Montaperti, 1486 - Siena, 1551). Beccafumi perfected the marble commesso technique to such an extent that he created unprecedented chiaroscuro effects with the marble slabs. In the great hexagon, Beccafumian intervention concerns the upper and middle sections, which can be traced back to the years 1519-1524, and has not been remade over the centuries. The Stories of Elijah and Ahab are told, in which we see the prophet’s triumph over idolatry, with the central theme being that of sacrifice. Each hexagon is accompanied by an inscription, but a slight discrepancy has been found between what is depicted and what is written. Elijah is seen as Jesus, but also as John the Baptist. The lower area, untouched by Beccafumi, was rearranged in the 19th century by Alessandro Franchi. In addition to the earlier continuation of the stories of Elijah and Ahab, to be ascribed to Giovanni Battista Sozzini, a number of parables were depicted.

Beccafumi’s next intervention is in perfect spatial and temporal continuity with the previous one: he was called upon to depict the episode Moses Makes Water Flow from the Rock, the cartoon of which is in the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena. The conformation of this panel makes it almost like a predella compared to the upper figuration, also by Beccafumi, in which the Stories of Moses on Mount Sinai are depicted. Finally, Beccafumi’s last intervention concerns the episode of the Sacrifice of Isaac, executed during a period when the Sienese artist was also engaged in work on the cathedral. This story is placed right in front of the high altar, the ecclesiastical space where, during every liturgical celebration, the sacrifice of Christ is made. It is therefore immediate to understand the choice of this biblical scene in this position: close to the high altar the theme of sacrifice is exalted, here maximized and reinforced by the presence of other biblical sacrifices, such as those of Abel and Melchizedek. It is the culmination and conclusion of the entire iconographic program of the floor. From the beginning of human knowledge, represented by Hermes Trismegistus, it traverses classical antiquity, the stories of the Jewish people, and the events of salvation history to finally arrive at the sacrifice of the Son of God, always evoked but never depicted, who frees humans from original sin.

The author of this article: Francesca Interguglielmi

Storica dell'arte, laureata in Arte Medievale presso l'Università degli Studi di Siena. Attualmente si sta formando in didattica museale presso l'Università degli Studi Roma Tre.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.