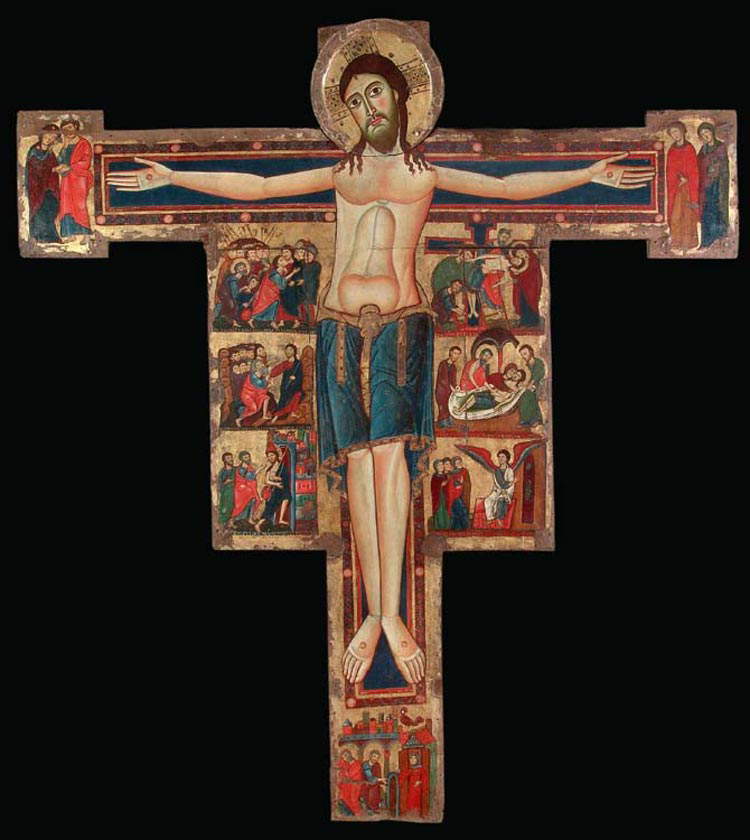

The spread of paper, beginning in the 1360s and 1370s, was one of the most important innovations in art history: until then, the preparatory drawing for a pictorial work was traced directly on the support. This was the way it was done in Byzantine times, when the drawing was traced on the plaster, either freehand or with the help of tools (it was necessary to have gained enough experience not to make mistakes, since the correction of any errors was definitely complicated), and this was also the way it was done in medieval painting before paper became a common material. Several analyses conducted on painted crosses, for example, have found this type of technique: take as an example the Rosano cross, a 12th-century work (probably painted around 1120), which has recently undergone reflectographic investigations aimed at determining what lies beneath the painting.

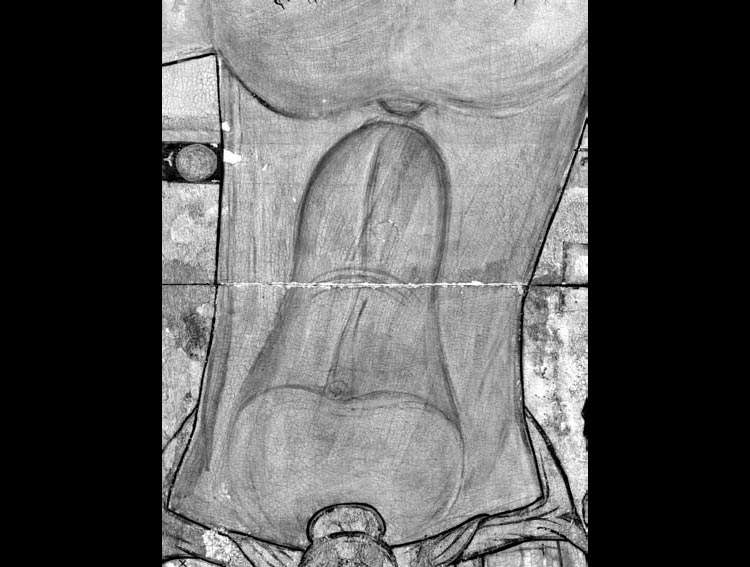

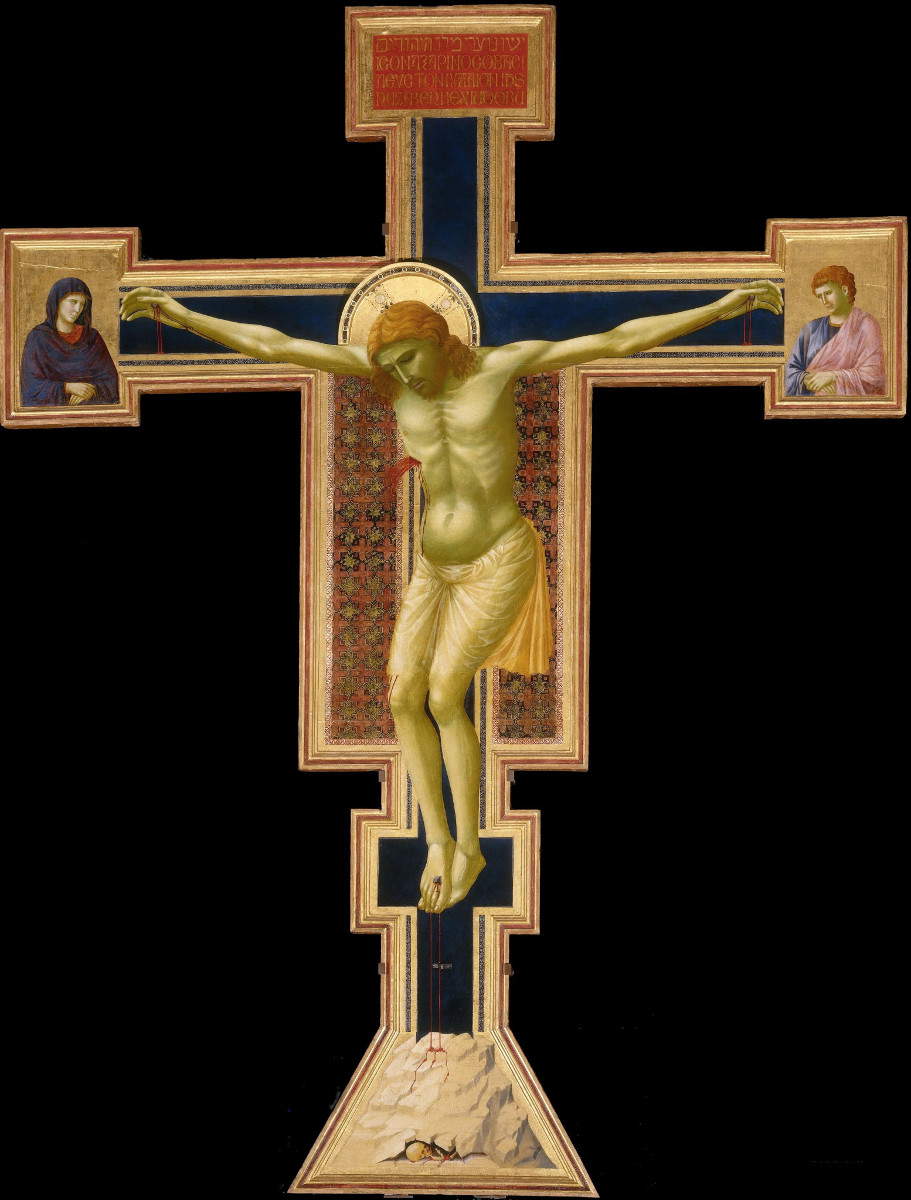

Reading the drawing, wrote scholar Roberto Bellucci in the study published after the investigations (reflectographs and X-rays are typically used to discover the underlying design), “made it possible to see that the painter first established the large fields of the side tabernacles, with a line, in charcoal, drawn with the aid of some tool, then partially erased at least in the areas where it was not needed (namely on the cross field) and at the separation between the scenes repainted with a freehand engraving.” After that, the artist traced, again freehand, the actual preparatory drawing to define the anatomical details within the engravings that served as a guide for the drafting of the colors: the analyses thus discerned great accuracy on the part of the artist in outlining strokes and shading for all the structures of Christ’s body. Of course, the technique could vary: in the Cross of Gugliemo at Sarzana, for example, the artist traced only the outline lines without shading, so as to accommodate a color drafting with flat backgrounds, while on the other hand in a much later cross, the one that Giotto (Florence?, c. 1267 - Florence, 1337) painted for Santa Maria Novella, a “substantially linear design has been identified that carefully builds the figure first in its fundamental volumes and then defines every minute detail by setting the plastic chiaroscuro of the figures already from this stage” (Marco Ciatti).

|

| Master of Rosano, Painted Cross (c. 1120; tempera on panel; Rosano, Santa Maria Assunta) |

|

| Detail of the preparatory drawing of the Rosano cross |

|

| Giotto, Crucifix (c. 1295-1300; tempera on panel; Florence, Santa Maria Novella) |

|

| Detail of drawing of Giotto’s Crucifix |

The spread of paper radically changed the way of working: it was possible to make a life-size drawing separately and then bring it, through various techniques, to the surface to be painted. One of these techniques was to cast with an awl: the tip of the tool was passed through the paper to leave a groove on the surface. For geometrically patterned decorations, the pierced mold technique could then be used: the design was traced on a sort of stencil through which the contours of the figures could be etched on the surface. Finally, a widely used technique, especially in Tuscany, was that of spolvero, which remained in use for centuries. Spolvero began to be extensively used in the fifteenth century for the creation of frescoes, when it gradually supplanted the sinopie technique: the latter involved making an initial charcoal drawing on the first layer of plaster, and once the artist was satisfied with the result, it was placed side by side with a drawing traced with ochre earth. The charcoal was then easily removed and, through the use of red earth, the ochre drawing was re-drawn: the artist had at this point a trace that he could follow very easily. A trace, moreover, that was particularly resistant, since the fall of the layers of plaster intended to receive the colors left uncovered, in many buildings, the sinopites.

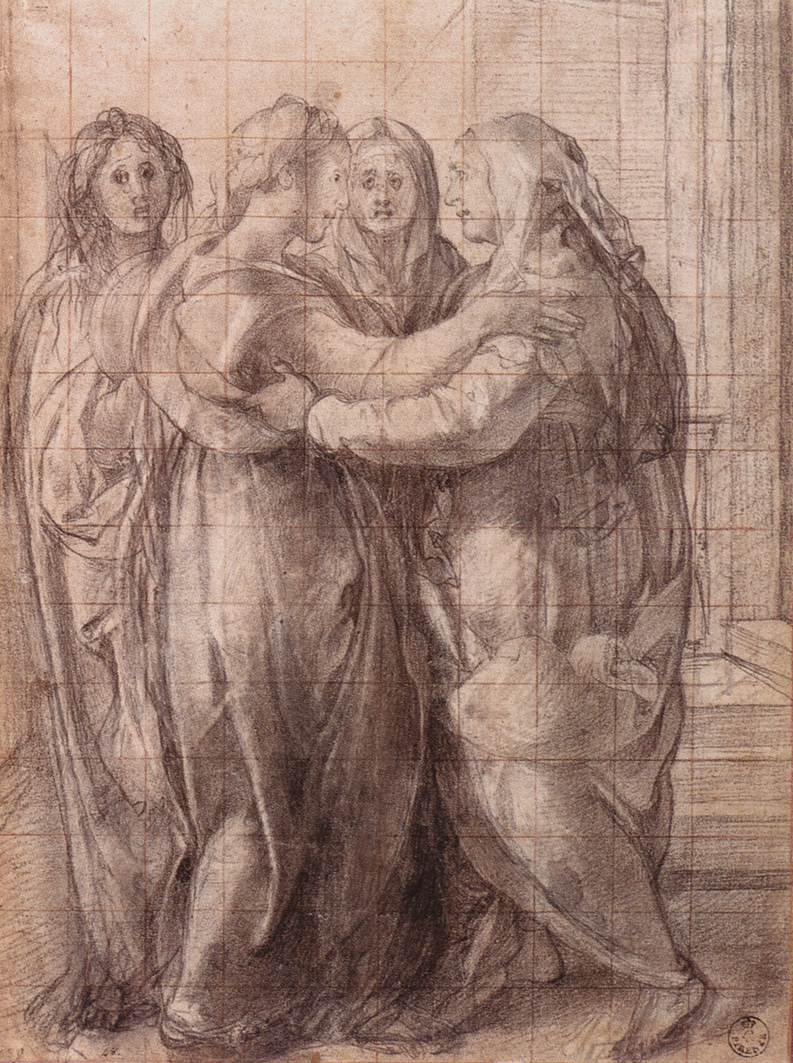

Dusting had the advantage of minimizing errors (because the drawing was done separately), as well as of being able to allow painters to replicate the same subject several times, always using the same drawing. Often they also started from smaller proofs, which were then fixed on a 1:1 scale thanks to squared sheets that made it possible to copy the proportions faithfully: we see this, for example, in the famous preparatory drawing of the Visitation by Pontormo (Jacopo Carucci; Pontorme d’Empoli, 1494 - Florence, 1557). The drawing was then very easily transferred to the surface to be painted (this could be either a wall for a fresco or a panel for a movable work). It was necessary to pierce with a needle the outlines of the final drawing (the so-called cardboard), which was then placed on the surface to be painted and dabbed with a canvas bag filled with charcoal (coal powder) or red earth: the charcoal, passing through the holes in the cardboard, left a precise trace on the surface, which the painter would be able to follow very easily.

Cennino Cennini (Colle di Val d’Elsa, 1370 - Florence, 1427) already spoke of dusting in his Libro dell’Arte, composed in all probability at the beginning of the fifteenth century: “according to the draperies you want to make,” we read in the celebrated tract, “according you make your’ dustings; that is, you have to draw them first in paper, and then pierce them with needle kindly, keeping under the paper a cloth or canvas; or you want to pierce in on a plank of tree or ver of linden: this is better than canvas. When thou hast pierced it, have it according to the colors of the cloths where thou hast to sprinkle. If he is white cloth, dust with charcoal powder bound in a piece; if the cloth is black, dust with white lead, bound the powder in a piece; and sic de singulis.” Other descriptions of dusting technique have been left us by great treatise writers. For example, Filippo Baldinucci (Florence, 1624 1696) defines the term “spolverizzare” (today we say “spolverare” instead) in the Tuscan Vocabolario dell’arte del disegno as follows: “vale ricavar collo spolvero, che è un foglio bucherato con ispelletto, nel quale è il disegno, che si ricava, facendo per quei’ buchi passarvi polvere di carbone o di gesso legato in un cencio, che si chiama lo spolverizzo.” The great painter Andrea Pozzo (Trent, 1642 Vienna, 1709), an outstanding master of fresco painting of the late seventeenth century, writes in Perspectiva pictorum et architectorum, “in the drawings of small things it will suffice to make a dusting, which is done by making thick and minute holes in the outlines, with dusted charcoal on top of it, bound in a rag that is apt to leave its less sensitive footprints. This by painters is called dusting.”

As mentioned, all the great Tuscan artists of the Renaissance used the spolvero technique for both frescoes and movable paintings: many of these cartoons still survive. One of the most famous is undoubtedly the so-called Cartone di sant’Anna, by Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), a great user of spolvero, who nevertheless did not disdain freehand drawing (recent investigations of theAdoration of the Magi inthe Uffizi have found to this effect that the drawing of this masterpiece was done entirely freehand: however, this was an eventuality that prolonged the work’s completion time so much that it was later abandoned, which can be explained by the fact that Leonardo was very young and overconfident at the time). Also of considerable interest is the drawing depicting Isabella d’Este kept in the Louvre, the eventual painting of which is not known: however, it has been suggested that it may have been indirectly used in the making of Giovanni de’ Predis ’Angel kept in the National Gallery in London. By subjecting paintings to diagnostic investigations, such as reflectography, it is also possible to trace the traces of dusting: in one of the most famous paintings in the Pinacoteca di Brera, Gentile and Giovanni Bellini’s Preaching of St. Mark at Alexandria, whose drawing was partly conducted freehand and partly reported, researchers have found signs of dusting (the small black dots) in the scroll held in the hands by the figure of the scribe.

|

| One of the sinopites from the frescoes in the Monumental Cemetery in Pisa (Pisa, Museo delle Sinopie) |

|

| Pontormo, Visitation (c. 1528-1530; black stone, traces of white chalk, red stone squaring on paper, 326 x 240 mm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery, Cabinet of Drawings and Prints, inv. 461 F) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Cartoon of St. Anne (c. 1500-1505; black chalk and white lead on paper, 1415 x 1046 mm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of Isabella d’Este (c. 1495-1500; charcoal, sanguine and pastel on paper, 630 x 460 mm; Paris, Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins) |

|

| Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis, Angelo (c. 1495-1500; oil on panel, 118.8 x 61 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| The drawing under the figure of the scribe in the Sermon by Gentile and Giovanni Bellini |

The most famous cartoon in the history of art is probably the celebrated preparatory cartoon of the School of Athens by Raphael Sanzio (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520), preserved at the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana in Milan: in 2019 its four-year restoration was completed. At 285 centimeters high and 804 centimeters wide, it is the largest Renaissance cartoon that has come down to us (as well as the only one of these proportions) and was made entirely by Raphael: the fact that it has come down to us virtually intact, unlike other cartoons, is due to the fact that it was not directly used for the transfer of the drawing, because given its perfection it was preferred to preserve it and use a replacement cartoon. That is, it was what was called a “well-finished cartoon,” that is, a cartoon so beautiful that it was deemed worthy of preservation. Raphael’s cardboard is also interesting in understanding how such challenging cardboard was made in terms of size. “First,” wrote scholar Maurizio Michelozzi in an essay devoted precisely to Raphael’s cartoon, “the artist would fix an initial idea of the entire composition in small sketches, the individual groups would then be studied in detail, coordinating them in a second drawing dassieme. Finally, the groups were again studied in detail with the aid of models from life, producing a new drawing dassieme, the so-called model, which was then squared off and brought back to a monumental scale on the ’well-finished cartoon.’ All this involved extensive production of preparatory drawings. The ’well-finished cardboard’ contained all the information necessary for the realization of the work: not only the outlines of the figures and the scenery in which they were to be arranged, but the movements, the expressions of the faces, the chiaroscuro and the origin of the light, providing an almost definitive image of what would later be the final result. Somehow it was as if all efforts were concentrated in the preliminary research, so that one would arrive at the painting having as precise and accurate a reference as possible.”

And because the cartoon was a very precise tool, the master was able to entrust much of the final execution of the painting to his collaborators. Raphael’s work has been in Milan since the 17th century: in 1610 it entered the collection of Cardinal Federico Borromeo, who obtained it on loan from Count Fabio II Visconti di Brebbia Borromeo. Upon the death of the latter, who was still formally the owner of the painting, his widow, Bianca Spinola, gave the cartoon for the sum of six hundred imperial liras to the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, founded by Federico Borromeo himself in 1607. The cartoon would leave Milan only on a few occasions: in 1796, when it was requisitioned by Napoleon’s army and taken to France (it returned to Lombardy in 1815), and during World War I (it was taken to the Vatican for security reasons). During World War II it remained in Milan, but was placed in the vault of the Cassa di Risparmio delle Province Lombarde to secure it. And after its restoration in 2019, it has returned to show itself to the eyes of the public.

|

| Raphael, Cartoon for the School of Athens (1508; paper, charcoal and white lead, 285 x 804 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca Ambrosiana) |

In the Renaissance, cartoons had a considerable importance, certainly higher than we attach to this type of work today: in particular, especially in Florence, it was customary to exhibit the cartoon of the work before it was finished. This was the case, for example, with Leonardo da Vinci’s aforementioned Cartoon of St. Anne and with the grandiose cartoons for the Battle of Anghiari and the Battle of Cascina, by Leonardo and Michelangelo respectively, which were executed in preparation for the scenes that were to decorate the Salone dei Cinquecento in the Palazzo Vecchio and which, however, were never completed. Probably a similar display involved the cartoon of the School of Athens. To understand the importance of the cartoons, consider that Raphael himself gave some of them to sovereigns and prominent personalities.

Nowadays, the pouncing technique has been replaced by more modern discoveries: for example, transfer through tracing paper (such as carbon paper) or the use of projections with slides or photographs. There are still painters who use it, however, and it is still taught mainly to help young artists practice drawing and its transposition to the finished work.

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.