What isabstraction in art? It is that “expressive sphere oriented toward analysis, inner research, even spirituality, devoted, by its intimate nature, to the highest index of freedom, placing itself, without reservation, before the viewer and his intimacy,” in the conviction that abstract art, as Peter Halley wrote, “must turn toward an intellectual dimension [...] and the work must not be for everyone.” This is the definition ofabstractionism according to Roberto Floreani, a painter and one of the leading contemporary Italian abstractionists: it can be found in his most recent book, Abstraction as Resistance, published by De Piante (380 pages, 25 euros, ISBN 9791280362124), which basically has two objectives: first, to trace a history of abstraction from its origins to the present, and second, to outline a state of the art by analyzing the landscape of contemporary abstraction, taking into account the fact that today art more generally is left on the margins of public debate.

One could start from the bottom, beginning with the title: why is abstraction a form of resistance according to Floreani? In a society as complex and problematic as today’s, and as superficial and materialistic at the same time, where people often live in uncertainty and lack of reference points, inundated with information, abstraction takes on the dimensions of an inner quest that can expand from art to invest other spheres. “In a historical period identified as recessive in its deepest contents and of abandonment to the most cynical materialism, where price determines value,” writes Floreani, “Abstraction, characterized by a constant search for interiority, already declared in the intentions of its most illustrious, can be considered, even today, an authentic embankment of spiritual resistance, an area where the work can convey an equally significant message, of the same nature” (an entire chapter of the book, entitled “The De-Spiritualization of the Contemporary and Abstraction,” analyzes this situation in detail). Floreani’s is also a critique of what he calls “Post-Art,” meaning by this term all those researches of artists, be they painters, sculptors, photographers or artists working with the means of installation, performance and so on, founded "more on image than on meaning. Post-Art, which, according to Floreani, has its pioneer in the figure of Marcel Duchamp, whose desecrating function with regard to the art of his time is nevertheless praised: today, for the author of the book, the roles, however, have reversed and even the most obtusely provocative and less meaning-packed art nevertheless enjoys great availability of economic resources as well as effective communication systems. Indeed, the book does not lack a relevant part devoted to the critique of the contemporary art system, assuming that today’s dominant Post-Art "curiously gathers not the indignant distance of those who cannot understand it, precisely because it is provocative, according to the lesson already known from the avant-garde, but an apparent uncritical, immediate, generalized, automatic mass consensus, driven by communication, triggered ad hoc with great economic availability and therefore, on the television model, persuasive.“ What is new compared to the past is that what the author calls the ”vanguard of consensus" has been produced, a situation that has never occurred before in history, “where what is incomprehensible to most automatically becomes apparent heritage to all, where there is no ’genuine desire to ask questions, but the inexhaustible eagerness to be present, the ambition to ’be there,’ boasting of a ’comprehensibility of the incomprehensible’ that is actually fictitious, pandering to those, now abused, 15 minutes of celebrity, albeit reflexively, announced by Andy Warhol.” It is a panorama of uncritical acceptance, where debate is also lacking, where very few personalities carry on a critical discourse (Floreani lists all those who, in his opinion, deal with it).

In all this, Floreani acknowledges thatcontemporary abstraction, compared to other types of art, enjoys less attention and moves in more underground channels, while still enjoying a coherent continuity with the research of historical abstractionists. Mention is made, among the most original contemporaries, of the American Peter Halley, who began his career in the 1980s, who is mentioned by Floreani as a leading figure, as is his countryman Philip Taafe, whose research combines abstraction and figuration by grafting them onto techniques typical of Pop Art such as silkscreen printing or collage: two artists, Floreani writes, who explored two different trends in abstraction: if in Halley “a kind of meditative detachment with spiritual outcomes predominates,” in Taafe there is a "strong emotional involvement: I constantly live in the painting while I paint it, as he will have the opportunity to declare, thus describing a hypnotic state, a condition of incorporeality, maintaining, on the other hand, always a technical control of the highest pictorial-compositional quality."

Mostly American artists are cited because, according to Floreani, the United States devotes attention to abstraction that is difficult to find elsewhere. In Italy, for example, in his opinion there is a marginalization that has well-defined roots, that is, it is due to the lack of attention that Italian institutions have devoted to what Floreani calls “the Italian way of abstraction”, but also to the same post-World War II Italian critics who saw alternating names openly hostile to futurism and who “avoiding an objective reconstruction of that period, distorting both its intent and meaning, made its influences difficult to interpret.” The revaluation of Italian abstraction is thus a recent fact, and Floreani cites the names of those who, virtuously, have begun to make up for decades of inattention and marginalization: the name of gallery owner Gian Enzo Sperone, the animator of some important exhibitions that have helped to relocate Italian abstractionists, stands out in particular.

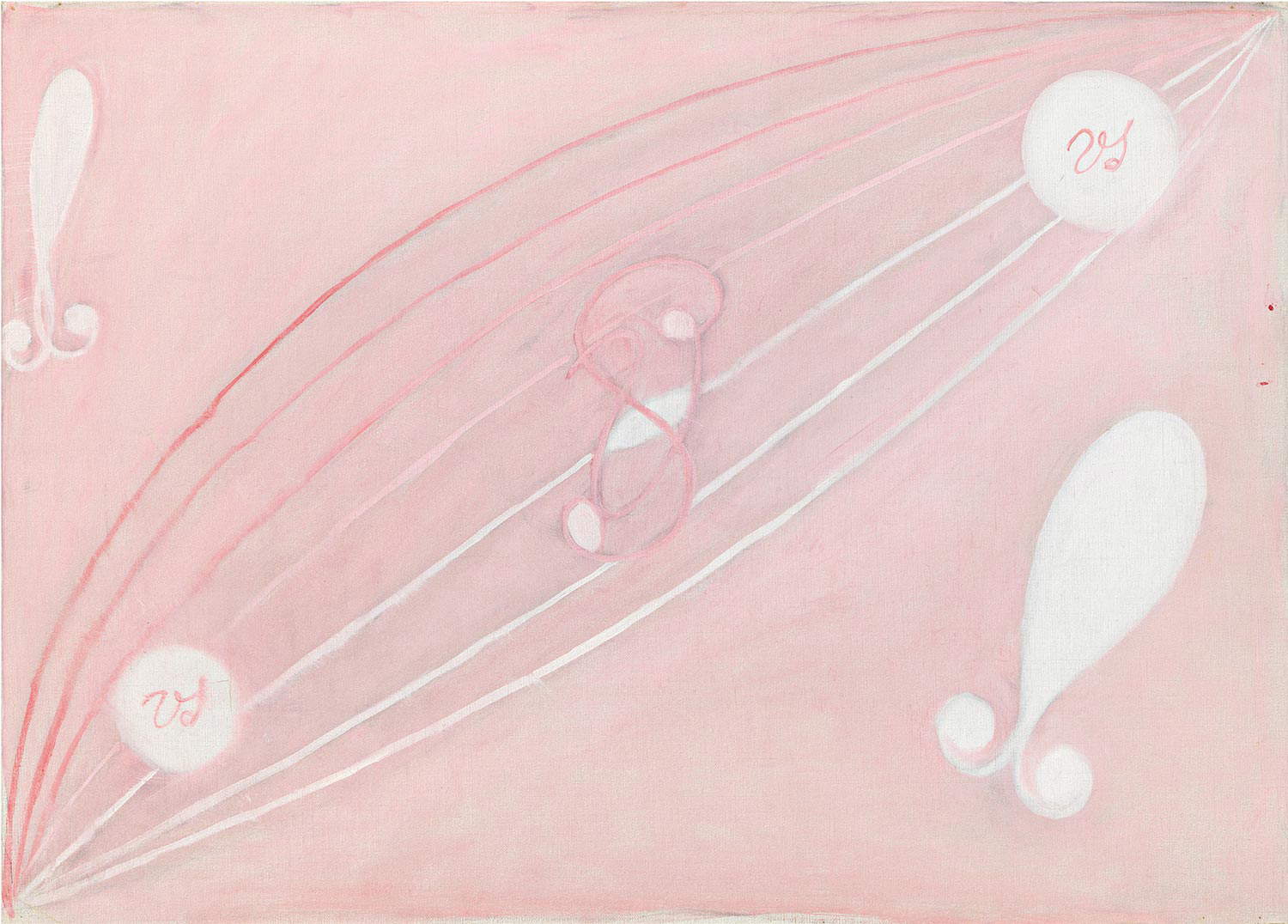

No less interesting than the sections of the book devoted to contemporary art, then, are those in which Floreani reconstructs the history of abstraction, not without significant novelties, which have been much discussed ever since Abstraction as Resistance came out in late 2021. Floreani, downplaying the role of Vasily Kandinsky who has always been considered the first abstract painter (for the author, things are different, and he also believes that the bearing of other figures of the time, starting with that of Kazimir MaleviÄ, were more significant in establishing, for example, “what art and in particular abstraction could conceive in its relation to ’elsewhere’”), he traces the origins of abstraction to some artists who worked in the late nineteenth century, and in particular Mikalojus Konstantinas ÄŒiurlionis, Hilma af Klint, and Marianne von Werefkin, proto-abstractionists who moved from Symbolist art in the direction of abstractionism, and he points out with profusion the decisive role of certain late nineteenth-century movements, such as the Theosophical movement, to which it is to be credited with having emphasized the ’latent powers ofman“ and of having contributed to having shifted the interest of artists to interiority rather than to observable phenomena (”in abstraction, from the very beginning,“ Floreani writes, ”the role of the artist and of the critic-visionary have added up and overlapped"). Belonging to this cohort of artists conditioned by Theosophy is a figure such as Hilma af Klint: recent research has shown that the Swedish artist can be considered the forerunner and first protagonist of abstractionism, ahead of Kandinsky (whose first abstract tests are moved by Floreani to 1913, and not 1910 as commonly believed, because her first abstract watercolor of 1910 was actually a draft of a landscape, as admitted by Kandinsky himself): in Hilma af Klint’s series Destined for the Temple , strictly abstract works, “already present,” the author writes, “are all the artistic-spiritual intentions that would later be advocated by Kandinsky, but elevated to the nth power and made at least four years earlier (in all likelihood six or seven).”

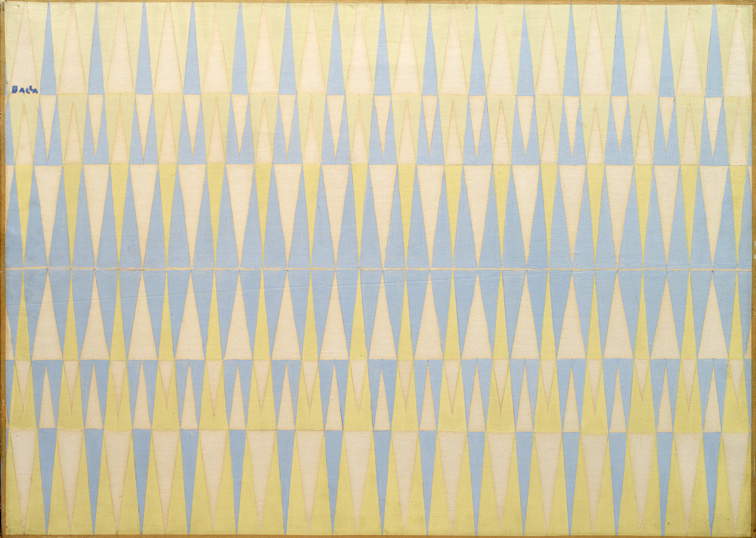

The Italian path of abstraction begins instead with Giacomo Balla and his Iridescent Comp enetrations of 1912, again a work that anticipates Kandinsky, as was already also been recognized by Raffaele Carrieri, who wrote that “his paintings after 1912 precede Kandinsky himself” and that “unlike Boccioni, Balla’s abstract syntheses are coordinated rhythms out of the object : motion in itself, without the object to determine it.” It is a different abstraction both from that of Hilma af Klint and Kandinsky, which seeks a way to express an inner feeling, and from that of MaleviÄ and Suprematism, which is purely rational abstraction: Balla’s abstraction is “scientific,” so to speak, and focuses on phenomena such as motion, speed, and iridescence, investigated nonetheless according to logics “governed by inner sensation.”

If, therefore, Hilma af Klint can be considered the progenitor ofexpressionist abstractionism, from which Klimt’s research will derive and, later, also that of the abstract expressionism of Pollock and companions, Balla is the founder offormal abstractionism. A primogeniture that ensures that many Italian abstractionists of the time, such as Balla, Severini, Dudreville, Evola, Magnelli, Prampolini and others no longer suffer “complexes of subalternity with respect to the precursors Delaunay and Kupka or even with respect to the teachers of the Bauhaus or the protagonists of the glittering Parisian market dominated by Picasso.”

Floreani’s examination then continues with the history of abstraction up to the present day, re-evaluating even experiences that are not so well known today, for example the Kn group gathered around the critic Carlo Belli and the Galleria del Milione (it counted artists such as Giuseppe Marchiori, Leonardo Sinisgalli and Dino Bonardi), or that of the Art Club founded in Rome in March 1945, until reaching situations that are instead much more established in historiography, such as MAC (Movimento Arte Concreta). He concludes with a few notes on Crypto Arte and NFTs, with Floreani warning the reader about the possibility of being faced with a “system conceived for profit,” a “phenomenon linked to the financial market that, with art, has, by its own admission, nothing to do with it.”

Abstraction as Resistance, with its historical-critical slant, its pressing narrative and the attention given especially to lesser-known experiences, or those to be re-evaluated, thus stands as a relevant essay both for rediscovering and reconstructing more precisely the origins of abstractionism and for assessing some lines of contemporary abstractionism. A book that, more than a year after its release, continues to raise debate.

|

| Abstract art as a form of resistance: artist Roberto Floreani's book |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.