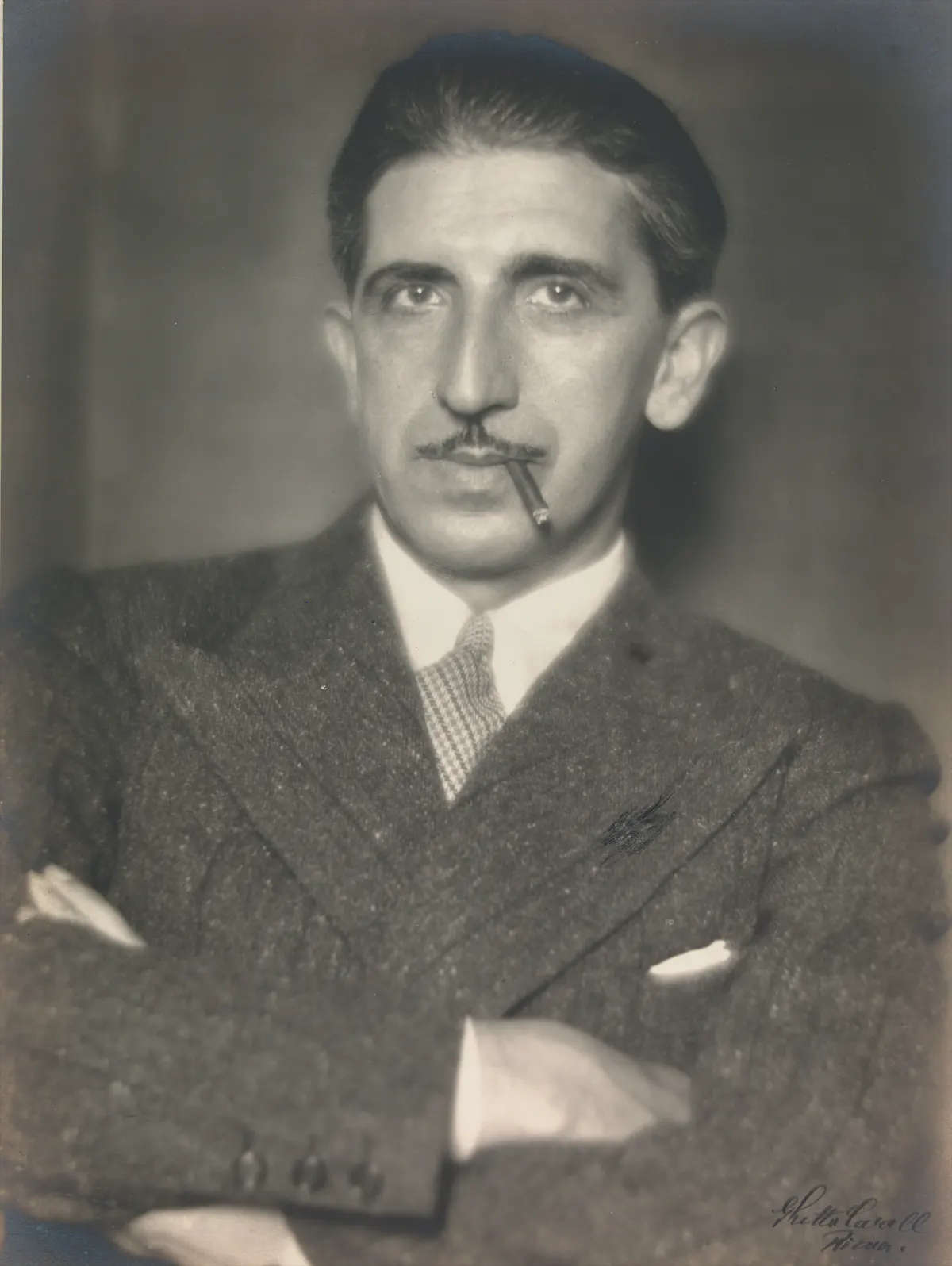

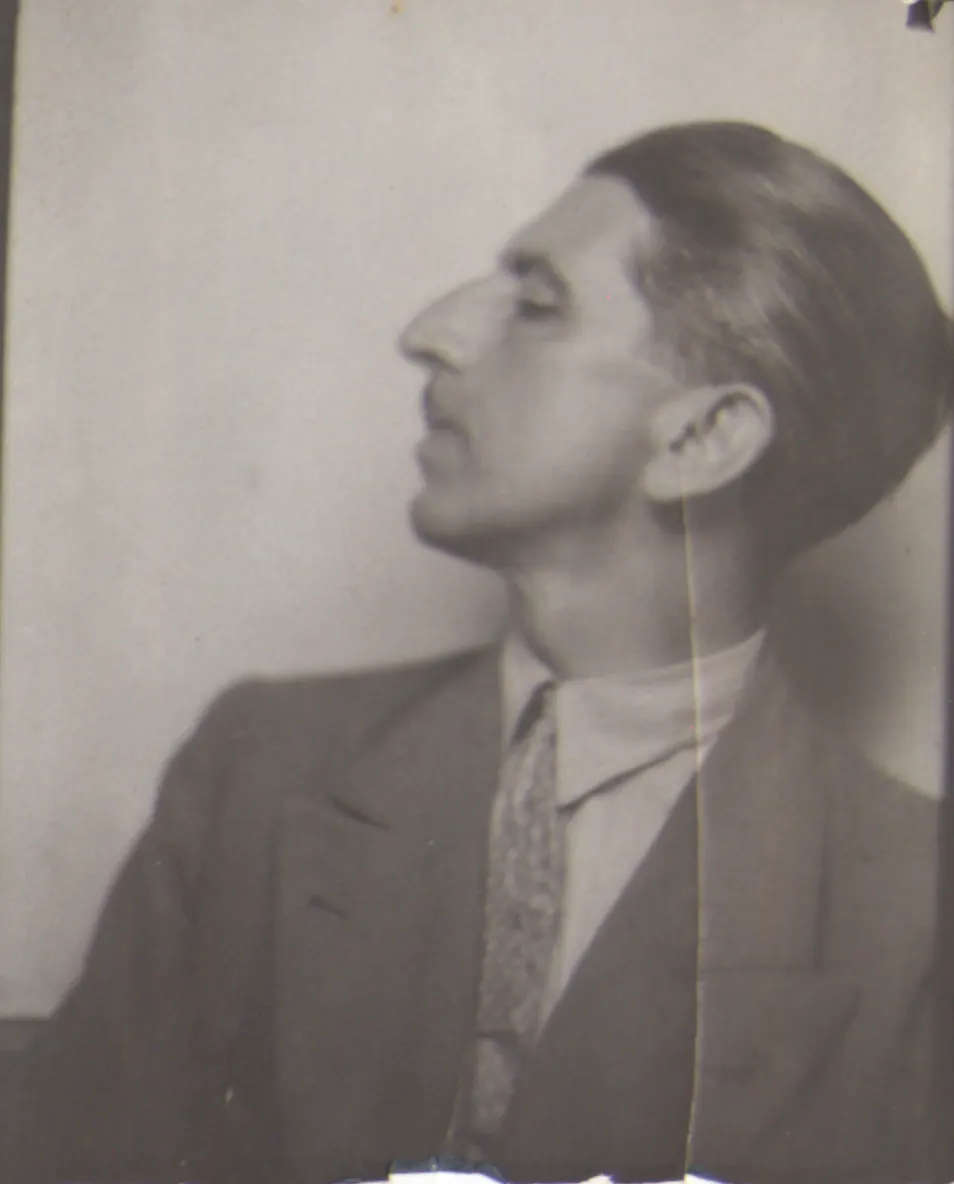

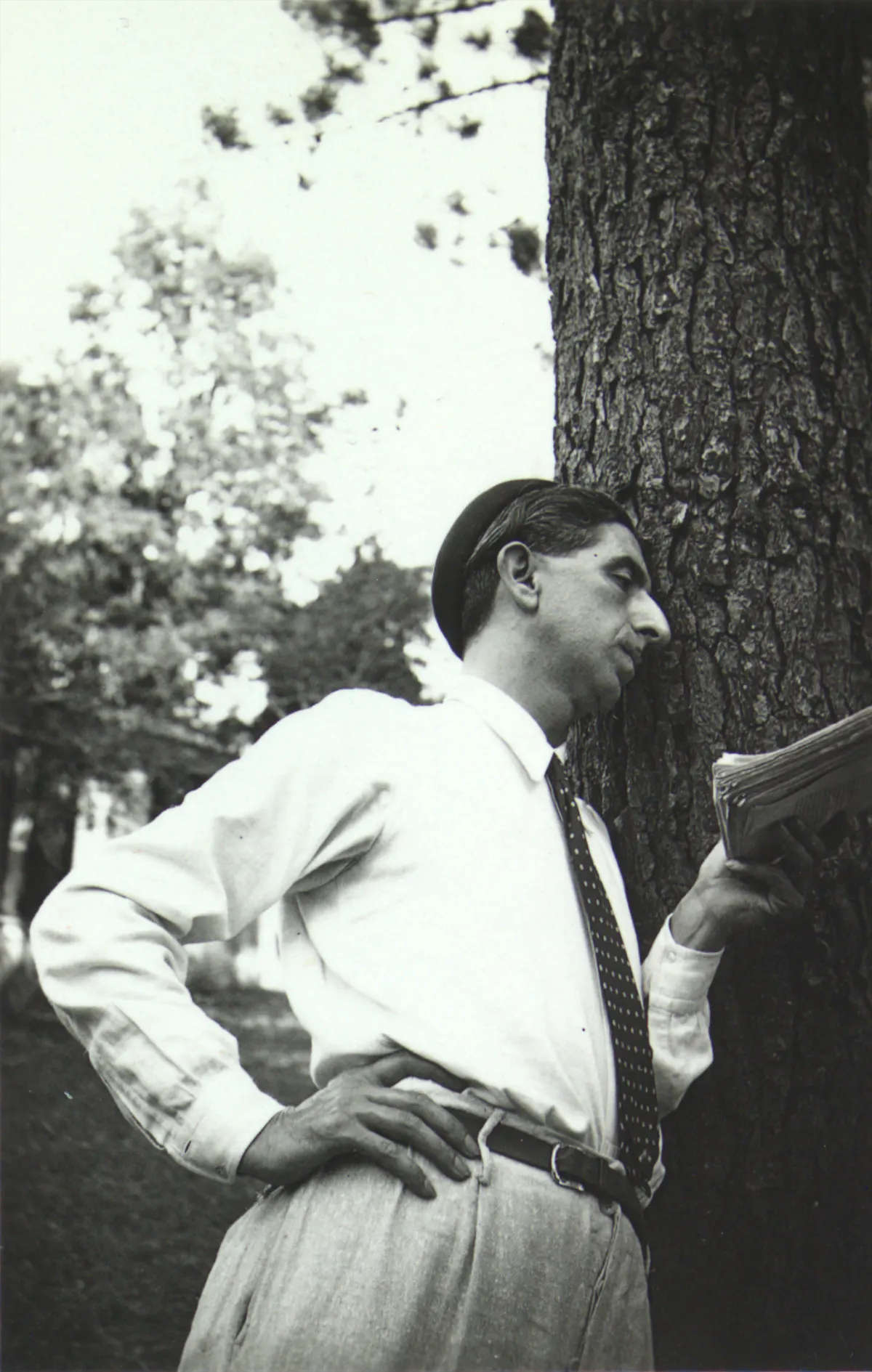

In the last decade, studies aimed at rereading the historical and critical work of Roberto Longhi have been several. A sign that Longhi has entered the phase of the historical process that will have to establish or not his definitive canonization. An arduous task when one considers that, for someone like Gianfranco Contini, Longhi was one of the greatest Italian prose writers of the twentieth century, but that abroad today he is little read and known because of his style of writing that makes him difficult to translate (another who pays the same price, and perhaps even more, is Giovanni Testori). A sign of this new attention to his path, a few months ago Einaudi published a collection of Longhi’s writings in the Millennials series. It is, in fact, a re-publication of the famous Meridiano Mondadori, which came out in 1973, three years after the critic’s death, edited by Gianfranco Contini (under the vigilant attention of Anna Banti), but with two additions: a core of color photos and critical notes drafted by 31 scholars as an introduction to each text in the anthology. Interestingly, despite the very different format of the two books, the pages of the Meridian and those of the Millennium are about the same (just under 1,200). The general editorship is by two experts on the subject, Cristina Acidini and Maria Cristina Bandera, who also draft the forewords, to which is added an introductory note by Lina Bolzoni, among the leading experts on the relationship between texts and images.

The valuable edition does not erase the substantial disagreement regarding the choice of eliminating from the volume the entire initial part that in the Meridiano summed up the texts by Emilio Cecchi, Gianfranco Contini, Giuseppe De Robertis and Pier Vincenzo Mengaldo, calibrated and intended to emphasize Longhi’s writing style and literary genius as an art prosatore. It could be said that in this approach, Longhi’s critical evaluations weighed less than his greatness as a writer, great even for his idiosyncrasies that, under the whip of such a tamer of beasts, became antiphrastic insights into paths to follow “backwards.”

It is not clear why take in toto the palimpsest of the anthology ordered by Contini, reproduce even its title From Cimabue to Morandi, without the slightest variation in the choice of texts, however, completely eliminating the apparatuses instead of updating them, thus misappropriating a work done by critics of rank, yet excluding their essays from this new edition. Why not instead supplement the volume with other famous texts not included here, for example the one on Caravaggio from 1952, to be placed next to the 1968 one published here, highlighting their conceptual differences? And perhaps add as an appendix the text of the introduction to the 1951 exhibition, pointing out that between the first edition of the catalog and the reprint a month after the exhibition opened Longhi made a few “corrections” to his introduction that were essentially stylistic in tone, proving that even the great have the temptation to correct printed books, but above all proving how much writing mattered in Longhi’s critical work. Because style is that stuff: recognizing what is yours deep down, what cannot be changed, like eye color or fingerprint, and giving proof of it in the field by reading reality, in this case artists, works and historical developments. And if this is the case, why exclude the Meridian’s introductory texts instead of moving them to an ad hoc appendix? It is as if one wanted to beat a different path from the one indicated by Contini, without being able to disavow its anthological palimpsest, in order to emphasize more the weight of Longinian critical insights within the historiography of art. But was it not from the outset a subject in which Longhi, as a prodigious connoisseur and critic, took pride in exhibiting precisely a language with poetic and literary lunges as a privileged means of interpretation and expression of his hand-to-hand with the subject of his criticism? Writing as a method, because criticism, contrary to what academics think, is a knowledge, not a science. And as such, every judgment has its own relativity, because it can be confirmed or changed by the same critic years later, even to the point of overturning his or her own opinions, if that is the case.

The remarkable fact with Longhi is precisely the tightness of his critical writing, even when it comes in the form of hyperbole (Testori, on this path, had followed him by adding the sonorities of the polymorphous writer who dealt, unlike his master, with poetry, novel, theater, political invective, transferring their substances into art criticism). That making works speak through verbal language, ecphrasis, is a choice that some of his own disciples perhaps no longer consider relevant (where are the critics today who know how to place an evocative word next to the work that is not reduced to technical or conceptual periphrases? I also addressed this question in the previous article on the Mendrisio exhibition). Whether it be curator’s masters or museum manager’s masters, or a substantial coldness of mind induced by the habituation to digital media that favor anaffective approaches, many today consider criticism a profession that can no longer operate without bowing to scientific instruments, to the varied diagnostics of images and materials, to the progressive analytical separation between the work and the artist. Longhi always defended the primacy of the eye, the advantage of the connoisseur: “first connoisseurs then historians.” In light of this, it would have been of great importance to place as an appendix to Longhi’s Millennium one of Longhi’s “paradigmatic” texts, the Proposals for an Art Criticism that kept the magazine “Paragone” in the 1950s. The palimpsest pointed across the history of critical literature is still, even in its eventual limitations, an example to ponder.

Longhi belongs to the history of literature for this as well; but his vision of critical language as poetic expression through ecphrasis, without receiving a rebuttal is, however, relativized by a historian and critic like the French Henri Focillon, who was able to express in the most classical a vision open to modernity, starting from the philosophy of Henri Bergson, particularly la durée and l’élan vital, which make him equally open to the human dimension before the humanistic one. Duration is the subjective perception of time while élan vital is that gap produced by human creativity that leads to evolutionary developments. Focillon’sIn Praise of the Hand remains one of the most pregnant theoretical texts produced by twentieth-century art criticism, as a pendant to Life of Forms: insights recapitulated by the French historian in the 1930s. His vision, in his case, does not depend on a generic openness to the experience of the concrete man, but on the “practice” that he accrued by acquiring skills in drawing, watercolor and printmaking by frequenting the workshop of his father, Victor Focillon, an artist without great genius but highly skilled in the exercise of techniques, including painting, from an early age. Focillon remains, also for this, and for his historical and critical essays, an author no less important than Longhi, so I always read with some perplexity statements such as the one in the title of Tommaso Tovaglieri’s essay Roberto Longhi “the myth of the greatest art historian of the twentieth century” published by Saggiatore. An excellent reenactment, an interminable six-hundred-page docufilm that calls to the stage the hundred characters who took turns in Longhi’s life, with the surprising choice to begin à rebours, from the critic’s death on June 3, 1970 in Florence. With the melodrama of farewells, Tovaglieri inaugurates his palimpsest, but essentially replicating from the beginning the absolute condition of the myth: “Longhi is able to see where no one yet sees,” that is, a diviner of the details that lead him to the identification of an author (this is also the substance of the famous “riddle” that Longhi proposed to his students by asking them to guess who was the author of a painting from a simple flap of the work). But this “reversal of the chronology of a life” serves as a methodology that seeks to hold together Longhi’s personal history and that of the diviner of art history. So, from Arcangeli and the other critics precepted in the Mendrisio exhibition, the mantra inevitably remains this: “we cannot but call ourselves Longhians.”

Again recently Keith Christiansen, one of the leading Caravaggio scholars, introducing the catalog of the retrospective mounted at Palazzo Barberini, quotes Bernard Berenson, who in his essay on Caravaggio’s “inconsistencies” wrote: “The sophistry of most literati, philosophers and critics is that they want to find the private life of an artist in the character and qualities of his art.” Thus Christiansen adds, “The present essay stands against the debasement of Caravaggio’s immense artistry and his success as a painter to a mere reflection of the external events of his biography.” To argue that in the Borghese’s Goliath Caravaggio painted his self-portrait of a desperate and melancholy man is to belittle him? On the other hand, if we were to claim, as I actually think, that Velázquez is the greatest painter of all time, hence Caravaggio’s as well, could this mean taking away from Merisi something of his absolute genius? Velázquez supreme painter, but Caravaggio more artist than him, you could say. That is, more capable of translating the human into pictorial form, perhaps with less perfection of execution. It is an old refrain that finds in imperfection the way to be perfect. And Caravaggio travels it to the end, just as Giambattista Marino in theAtlas Dwarf writes: “And who will say that of every other Christian / I am not more graceful, and more gallant, / if in me becomes grace even the defect, / and imperfection makes me perfect?” Caravaggio was certainly not as ironic, but the question must be asked: do certain imperfections, for example when he has to paint his hands, make his art less great? “But there is no evidence that Caravaggio considered his art a vehicle for expressing his personality. Nor is there any evidence of an artist obsessed with introspection, as in the case of Rembrandt, in whose incomparable series of self-portraits we seem to see the evolution of his self-construction as an artist and as a human being,” Christiansen concludes. I leave it to the reader to determine to what extent such statements are compatible with what we know and see of Caravaggio. I do want to point out, however, that bringing up Berenson and arguing for the mismatch between the work and Merisi’s introspection has the flavor of a distancing from the Longinian and, if you will, Bantian line.

In the exhibition catalog Caravaggio and the Twentieth Century. Roberto Longhi, Anna Banti, at Villa Bardini in Florence until July 20, Fausta Garavini writes, about Anna Banti, that "the beautiful Lotto can be said to be a ’Longhian’ book because of its search for a figurative language that recreates with the pen, so to speak so to speak, the work of the brush; Anna Banti’s pen, however, is that of the novelist who, if she shows herself to be a sensitive reader of the paintings, reconstructs together the troubled vicissitudes of the artist with the intention of snaring the man in the painter.“ The writer was aware that this path could lead to mistakes, but ”more than the simple restitution of facts, fiction allows one to approach the truth." If Berenson, knowing that he was hurting Longhi’s pride, said that the genius of the family was her, Anna Banti, born Lucia Lopresti (an idea, moreover, shared in his own way by Emilio Cecchi himself), it can be observed instead that after meeting his future consort, Longhi’s language evolved from thehistrionic expressionism of Voce’s brand, in which he also excels in plastic inventions, toward a more literary form, though still evocative, where the linguistic mimesis that generates ecphrasis moves with the humility of one who is aware that between image and word there can never be an identification because they are two idioms of a different and irreconcilable nature.

The Florence exhibition, curated by Cristina Acidini, president of the Longhi Foundation, and Claudio Paolini, is accompanied by a catalog published by Mandragora, rich in iconographic material, with various insights into Banti, who emerges as the faithful custodian of Roberto’s work, but also experiencing after Longhi’s death a different freedom in her own authorship. The masterpiece of the award-winning firm Il Tasso-the home of the two authors-was the creation of the magazine “Paragone” in alternating issues devoted to art and literature. The stage on which to do criticism is inscribed in the very materiality of the issues that have been coming and going since 1950 month after month. The idea certainly came from Longhi, who had already founded and directed other art magazines, but the birth of the periodical was undoubtedly a shared initiative with Anna Banti, although the cover of the issues read “Founded by Roberto Longhi.” And it is precisely this “in-house” separation of expertise-artistic/literary-that reflects a subtle antagonism that has long penalized Banti compared to the myth that Longhi would definitively become after the 1951 Caravaggio exhibition. A shadow that little by little is thinning to make room for the judgment of Banti as one of the greatest Italian writers of the twentieth century.

Rather, the exhibition catalog is a book by various authors, twenty to be precise, which is followed by a registry of the works on display, which is almost marginal in the volume and in the sequence of which the numerous portraits that Longhi made of his wife should be noted. The only drawback is the title, which once again exploits the myth of Caravaggio, whose Ragazzo morso da un ramarro (which is actually a lizard) is exhibited to attract the public. But it should not be forgotten that Longhi’s collection, features works by Borgianni, Valentin de Boulogne, and Jusepe de Ribera (but knowing that Longhi disliked Ribera’s painting because it was too analytical, which was why he did not understand that Spagnoletto’s hand was the same as that of the Master of the Judgement of Solomon, which he believed was from the French area, a restitution that occurred 20 years ago with Gianni Papi’s essays that had the effect of reconsidering Ribera’s own influence in Rome before his departure for Naples). The great ruler of the exhibition is, of course, Morandi (just as Longhi texts dedicated to him also close the Meridiano/Millenni anthology), with eleven works, joined by Carrà, Morlotti, and Maccari.

Among the essays that have come out in recent years is the one by Marco M. Mascolo and Francesco Torchiani, Roberto Longhi. Percorsi tra le due guerre, published by Officina libraria is perhaps the one that made me reflect the most on some of the issues that have emerged in the last two decades, convincing me that we are now at the nodal point where in order to valorize Longhi it is necessary to “demythicize” him; to “revise Longhi,” for example, beginning with his antipathies. It is a matter of doing a maintenance of the myth without dismissing it. And starting with Keine Malerei (“No Painting”)-the title of an essay written in 1914, and which remained unpublished until 1995, when Il palazzo non finito, a large volume of Longhi’s unpublished works compiled between 1910 and 1926, came out for Cesare Garboli’s editorship-may bear useful fruit for the overall reconsideration of his work. In that “idiosyncratic” essay Longhi attacked all Northern Renaissance art without half-measures. The tone was saccharine: “... Or will this obnoxious lamb finish once and for all slipping on the sloping lawn all the way into the fountain.... ” (he was emptying his poison glands expressing his dislike for Van Eyck and theAltar of the Mystic Lamb in Ghent). Dürer, Holbein, Fouquet, Memling, and various other French, Flemish, and German painters were also being preached in the Keine Malerei team: “all together - nothing,” the prosecutor mercilessly concluded. What irked him? He could not bring himself to like Nordic realism in which he saw nothing but a technical exhibitionism, mimesis of reality, but without art.

Mascolo and Torchiani’s book is useful for the punctuality with which it summarizes the great critic’s intellectual surges: from his contrasting relationship with Croce’s aesthetics - followed with reservations in his youthful years, with distances taken on idealistic abstractions, and then a return in the 1940s to Croce’s positions useful in extricating himself from that murky phase that saw him as Bottai’s ministerial collaborator -, to his resignation from the University of Bologna, where he had risen to a professorship in 1934, with the advent of the Social Republic, but first with the famous Florentine conference of 1941 on Italian Art and German Art, where youthful idiosyncrasies, albeit with unsurpassed reservations about Dürer, dissolved in an evaluation that can be summed up in the idea “to distinguish in order to unite” (in a non-racist and non-nationalist sense). The universal in the particular, in short, beyond all regionalism.

Longhi was never an opponent of fascism: in 1932 he had had the party card without which it was difficult to do anything in Italy, and in 1935 he had sworn allegiance to the regime; “bureaucratic routine” which, put like that, makes one cringe, since his “compromise” with political reality did not fall even when the 1938 Racial Laws passed, a period when he was in Rome co-opted by Bottai. Garboli sums it up effectively when he speaks of the syndrome that “stuck with him all his life, like the dandruff that shone more and more, with time, on his blue cashmere jackets,” or the "Longhi Keine Malerei.“ ”avant-gardist, futurist, idealist, actualist, nationalist, anti-passatist, vocalist," which commutes with a “whimsical, smoky, untranslatable language, made to amaze, enchant, seduce, made to express rather than to communicate, and intended only for compatriots.”

Finally, I want to mention that Longhi after graduation was in Rome and collaborated with Adolfo Venturi and the magazine “L’Arte.” At that time Aby Warburg was also in Rome to talk with Venturi about the organization of the 10th International Congress of Art History to be held in 1912 at Palazzo Corsini on the same theme that Longhi in 1914 would take up head-on: Italy and Foreign Art (essentially Northern European art ). Here Warburg made known the famous zodiacal interpretation of the frescoes in Palazzo Schifanoia. At the time, some German scholars saw in the art of southern Europe-as archaeologist Julius Schübrin put it-a “compulsion of blood and instinct.” Recently Hans Belting wrote that in the expectations of the Prussian government at that congress the game of “Germany versus the rest of the world” was being played out. Longhi certainly followed the discussion, but I ignore whether he met Warburg (certainly the report on the Schifanoia frescoes, however conducted on allegorical and symbolic lines, must have attracted his attention). The Nordic superiority that German historians were expressing in their reports two years later may have fanned the fire of Keine Malerei and Longhi’s pride.

The author of this article: Maurizio Cecchetti

Maurizio Cecchetti è nato a Cesena il 13 ottobre 1960. Critico d'arte, scrittore ed editore. Per molti anni è stato critico d'arte del quotidiano "Avvenire". Ora collabora con "Tuttolibri" della "Stampa". Tra i suoi libri si ricordano: Edgar Degas. La vita e l'opera (1998), Le valigie di Ingres (2003), I cerchi delle betulle (2007). Tra i suoi libri recenti: Pedinamenti. Esercizi di critica d'arte (2018), Fuori servizio. Note per la manutenzione di Marcel Duchamp (2019) e Gli anni di Fancello. Una meteora nell'arte italiana tra le due guerre (2023).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.