Rummaging through the RAI archives, it is possible to find, even with some ease, an interview by Ugo Gregoretti with one of the greatest Italian designers of the second half of the 20th century: Alessandro Mendini (Milan, 1931 - 2019). The interview focuses on what is probably Mendini’s most famous creation: the celebrated Proust armchair, named after the seminal French writer, Marcel Proust, author of the novel In Search of Lost Time. A lost time that seems to be evoked by this extravagant armchair, which Mendini designed in 1976 and made in 1978. “The most photographed of Italian armchairs, perhaps the physical majority of our armchairs”: this is what Gregoretti called it, beginning the interview.

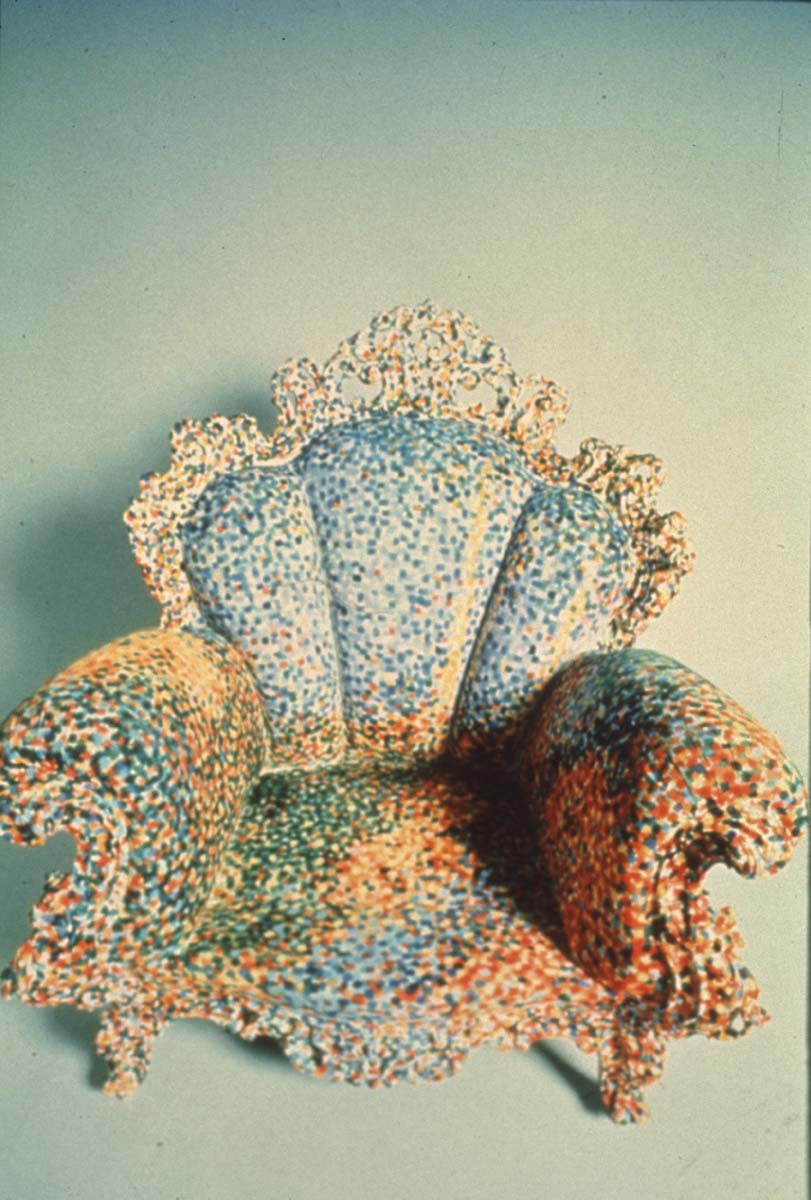

And indeed, if one tries to think of a designer armchair, the first name that will most likely come to mind will be that of the very famous Proust. An armchair designed with particular attention to form, using a combination of sinuous curves, extravagant lines and Baroque reminiscences to create visual harmony, all combined with an imaginative fabric directly inspired by French pointillisme . A wood and fabric armchair that imitated antique seating to offer its very rare purchasers literary sensations. High upholstered back, wide armrests with two wide swirls to also offer comfort to those sitting on it: an object designed for reading, for conversation, born, however, more to convey an idea than to actually fit into a domestic setting.

The birth of Proust occurred almost by accident. Starting from two ready-mades, as Mendini himself would declare in the famous interview: it is therefore a piece of “re-design,” according to the artist. The first ready-made is a faux eighteenth-century style armchair that the designer had found in a little market in Veneto, during one of his trips. A kitsch object, in short: Mendini had no problem admitting it. The second is a lawn from an unspecified painting by Paul Signac, who along with Georges Seurat was the leading exponent of pointillism(or pointillisme). From this combination Proust ’s form and color were born. And why finally the reference to the man of letters? The Recherche, Mendini himself said in an interview with Repubblica, “has been for me an infinite reading, an interweaving of sequences without beginning or end. It reflects the path of my life. Besides, Proust interested me because of his relationship with painting. Not so much the one he loves and finds in Vermeer, but the one coeval with him: pointillism and pointillism, in which each brushstroke has its individual strength and the image shatters, breaks up and recomposes itself in a kaleidoscope of colors, as precisely in Signac and Seurat.”

![Alessandro Mendini, Poltrona Proust prodotta per studio Alchimia (1978 [1981]; poltrona dipinta a mano, altezza 109 centimetri; Londra, Victoria and Albert Museum) Alessandro Mendini, Poltrona Proust prodotta per studio Alchimia (1978 [1981]; poltrona dipinta a mano, altezza 109 centimetri; Londra, Victoria and Albert Museum)](https://cdn.finestresullarte.info/rivista/immagini/2023/2249/alessandro-mendini-poltrona-proust-v-e-a.jpg)

“To design an object,” Mendini explained to Gregoretti, “there are many paths and many can be the goals one wants to achieve. In this case, I was interested in designing an armchair starting from a literary path and feeling: Proust. When you read Proust, you have great environmental and interior sensations, it is very rich in this environmental setting. I imagined what a Proust armchair could look like. I also inquired, I visited his places, I understood that he was someone close to the pointillists in Paris, and therefore I thought of pointillism as a place also of immaterialization of the object, that is, as a tendency toward atmosphere rather than physicality.” Of course, we will never know if Proust would have agreed with Mendini. Or whether he would have enjoyed sitting in his chair. One thing we can agree on, however, as Silvana Annicchiarico noted in her book 100 Objects of Italian Design: “Proust’s armchair has as much to do with research as it does with memory and time. The lost one, the one that is lost.” In the historical period in which it appeared, the late 1970s, Proust posed itself, Annicchiarico explains, as “an object that attacks and dissolves the traditional connotations of rationalist design (originality in form, functionality, mass production) in a key judged - from time to time - romantic or transgressive.” Mendini’s armchair, moreover, was envisioned as a unique piece. The Milanese designer had thought of something rich, as well as an object that was indeterminate both geographically and chronologically: “I was also interested in the paradox for which this object that was to be born had no date, no philological referability.”

A Baroque armchair, a nineteenth-century fantasy, all dropped into a context in which rationalism was giving way to postmodernism. And indeed, even Proust can safely be read as a postmodern work of art: the high culture of Proust and Signac is reinterpreted to create a bizarre, ironic, peculiar, surreal, even playful armchair. Not coincidentally, Proust was first exhibited, when it was still to remain a unique piece, at the exhibition Incontri ravvicinati di architettura, organized in 1978 at Palazzo dei Diamanti and curated by Andrea Branzi and Ettore Sottsass: an avant-gardist, and the one who would shortly become Italy’s greatest postmodernist designer. That same year it was then exhibited as a work of art at the Venice Biennale. That first example was hand-painted by Prospero Rasulo and Pierantonio Volpini. The armchair was then purchased by artist and fashion designer Cinzia Ruggeri, and her studio, Alchimia, produced a number of pieces, probably fifteen, all for selected collectors (Mendini signed some but did not bother to record the numbering). The artist Franco Migliaccio would later be responsible for the decoration with acrylic colors. These armchairs later ended up in various museums, such as the Groninger Museum in the Netherlands or the Vitra Design Museum in Weil-am-Rhein, Germany, or even the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Museo del Mobile in Milan’s Castello Sforzesco, not to mention those that went to decorate the homes of collectors.

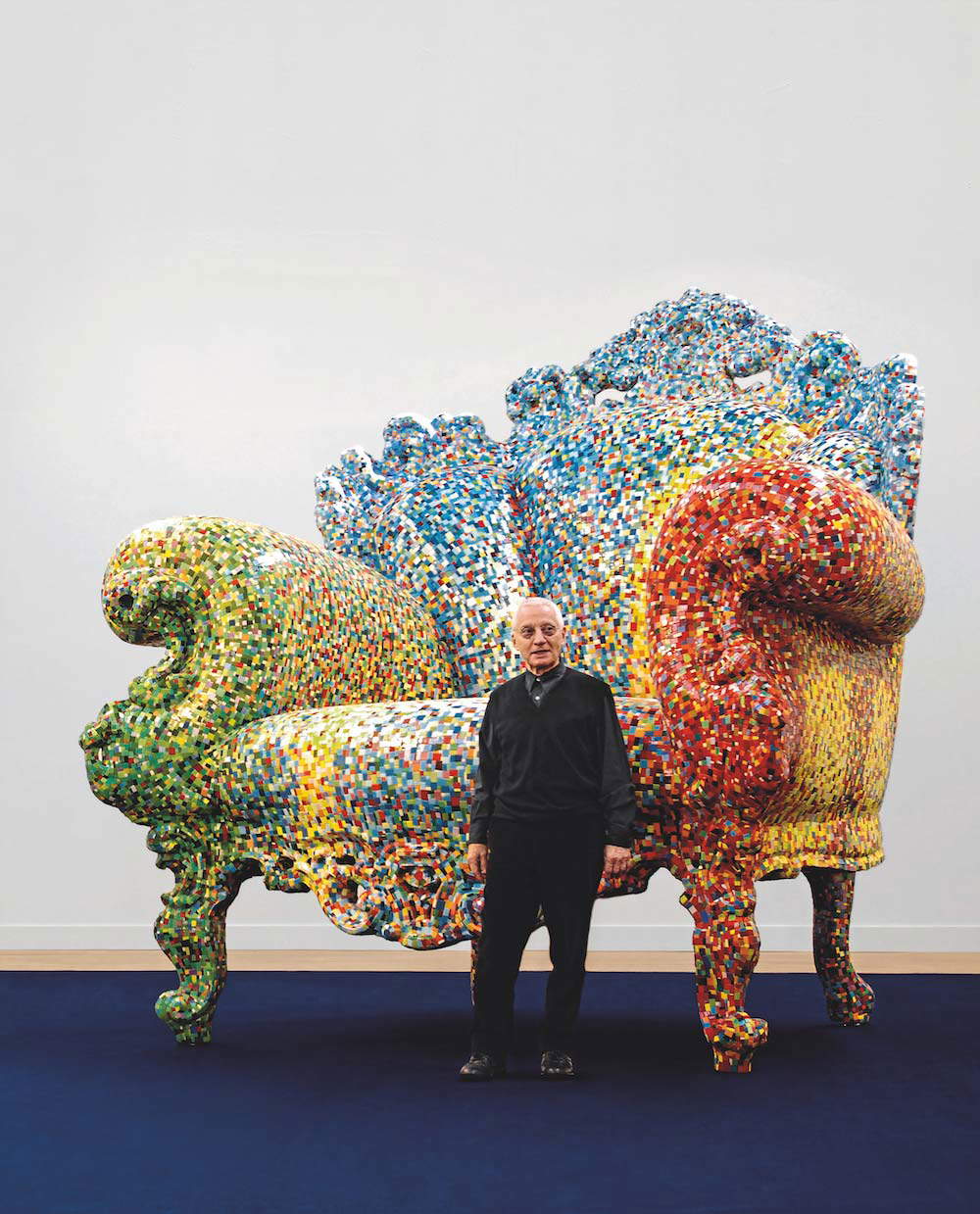

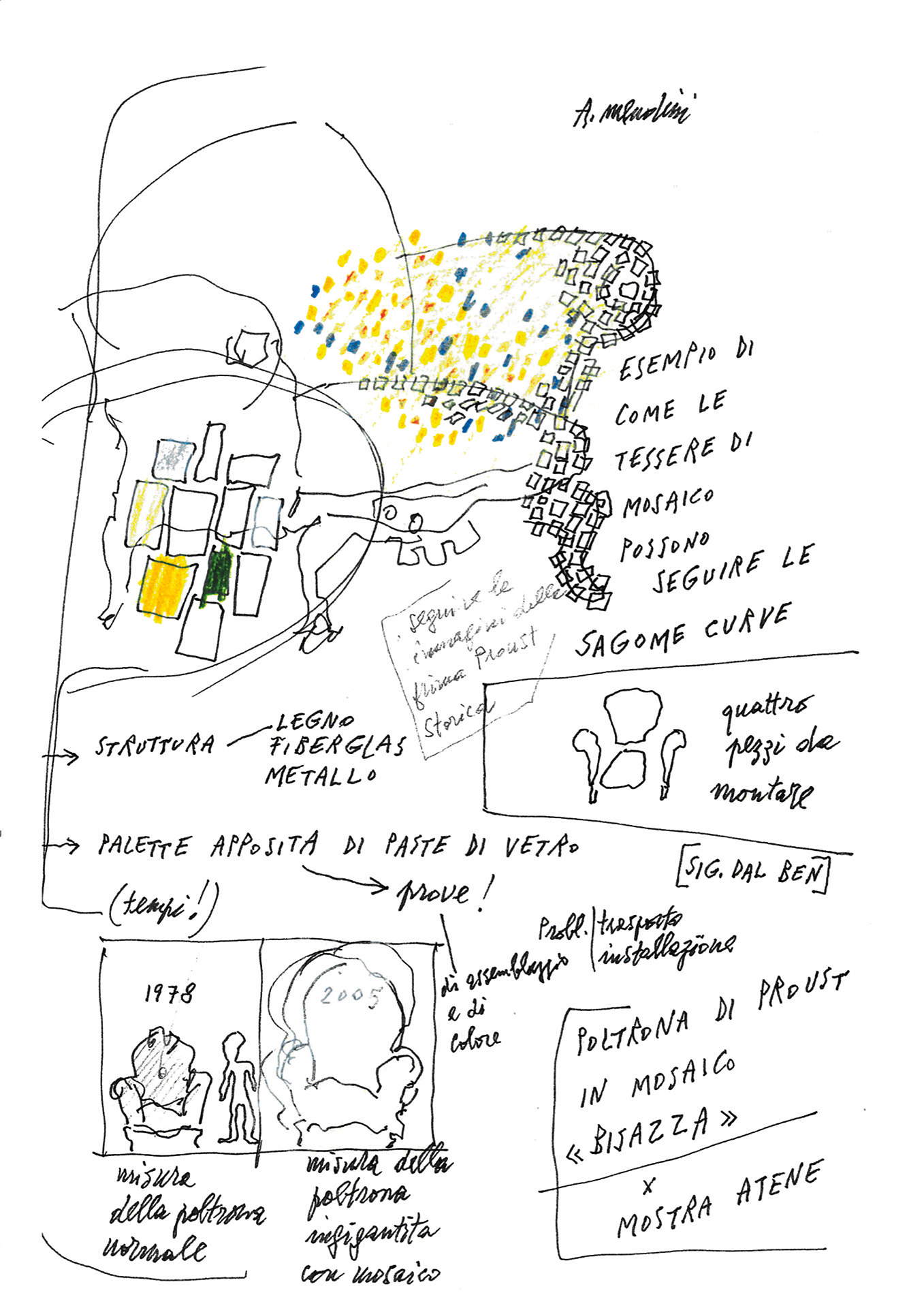

Mendini wanted to pay homage to the great man of letters through an armchair directly inspired by his work. Not only that: by his own admission, his ambition was to create a cultural object from a fake, from a kitsch piece, from an object from mass, mass production. A “fascinating mind game,” as Mendini himself would later declare. And he succeeded in creating an icon of Italian design and a work of art appreciated all over the world. So much so, in fact, that Mendini was later convinced to start a small production. It happened in 1989, first with three pieces created experimentally under Mendini’s direct supervision. Then two more in 1991. More pieces would follow: for example, in 1999 a custom one for theater director Bob Wilson. Finally, in 1994, it entered the catalog of the Cappellini company, which started serial production, although the prices were far from affordable. All with colorful fabrics: there followed, for example, the Yellow and Black Proust, the Geometric Proust, the Cimarosa Proust, the Paradise Proust, and many others. In 2005, for the Art of Italian Design exhibition in Athens, Mendini produced, at the suggestion of Piero Bisazza, a Proust of monumental dimensions (“it is no longer just an armchair, it is a sculpture and perhaps an architecture,” Mendini said on that occasion). Even, in collaboration with the Carrara-based company RobotCity , Mendini created one made entirely of Apuan marble in 2014. In addition, the “real” armchairs were joined by small ceramic miniatures in limited editions. Finally, the Proust designed for outdoors, outdoor version in short, produced by the company Magis.

However, the true soul of Proust remains that of a design object that can also be considered a work of art: in her book L’ornamento non è più un delitto, an essay on contemporary decoration, the architect and designer Cinzia Pagni includes it among the creations of “artistic designers,” or those creators who “lend themselves to the world of design as true artists, creating objects that become ’unique pieces’ in limited editions, somewhat at odds with the very definition of industrial design.” Designers of this kind can therefore afford very free research that looks not only at forms and concepts, but also at the study of materials and, above all, at the meaning of their products, introducing into design “research and poetry, between innovation and tradition, between the needs of the public and corporate strategies.” This is why, therefore, it is often easier to find Proust inside a museum than inside a house.

Yet, that same object that was meant to be a unicum ended up later becoming a mass-produced product. Limited series of course, but still produced according to a different logic than the one that had led to Proust’s birth. And then, Mendini’s armchair itself became a “symbol of neokitsch design,” as scholar Andrea Mecacci has written (or “conscious kitsch,” according to a definition by Mendini himself). Here, "the poetics of double coding,“ Mecacci rightly wrote, ”is at its most recognizable." Double coding literally means “double register,” and is a notion formulated by architect Charles Jencks, the principal theorist of postmodern architecture: it is the characteristic of certain kitsch objects to speak simultaneously to both elites and the man in the street. And Mendini’s armchair succeeds very well in this operation.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.