At the inauguration of the important exhibition dedicated to Verrocchio, Leonardo’s master, the editorial approach adopted for the catalog was revealing1: in fact, the front cover shows a detail of a painting, while only in the back cover does the detail of a sculpture appear, namely the famous hands that the Lady of the Primroses brings to her chest by brushing it with her bouquet. Since in the dense bibliography pertinent to the personality of Andrea del Verrocchio he is the object of study mainly as the author of works of sculpture, the choice revealed the intention to focus attention not only on the plastic, but also, and with determination, on that pictorial production of Verrocchio’s workshop which, even amid differences of opinion, part of the critics referred to some of the master’s collaborators. It therefore legitimately and openly contradicted the text of Vasarian Lives2, which describes Andrea as an artist who lacked “facility” but was rather inclined to “study,” and as renouncing the technique of painting in favor of a pupil, specifically Leonardo. There is no need to recall here how many and what reasons have led critics to retouch, correct and refute very many passages in the Lives, moreover in the face of just as many forms of validation and enhancement that the same critics have given to other passages in Giorgio Vasari’s work; nevertheless, in the case of Verrocchio, the Vasarian profile describing an artist/intellectual inclined to vary the register of his style, slow in his work and sometimes explicitly tardy, turns out to be in some respects still justified; while in my opinion theidentikit provided by Caglioti and De Marchi presents some cracks: That of a hyperactive teacher, who in addition to having full possession of multiple skills, operated concretely by practicing different ways of working and techniques.

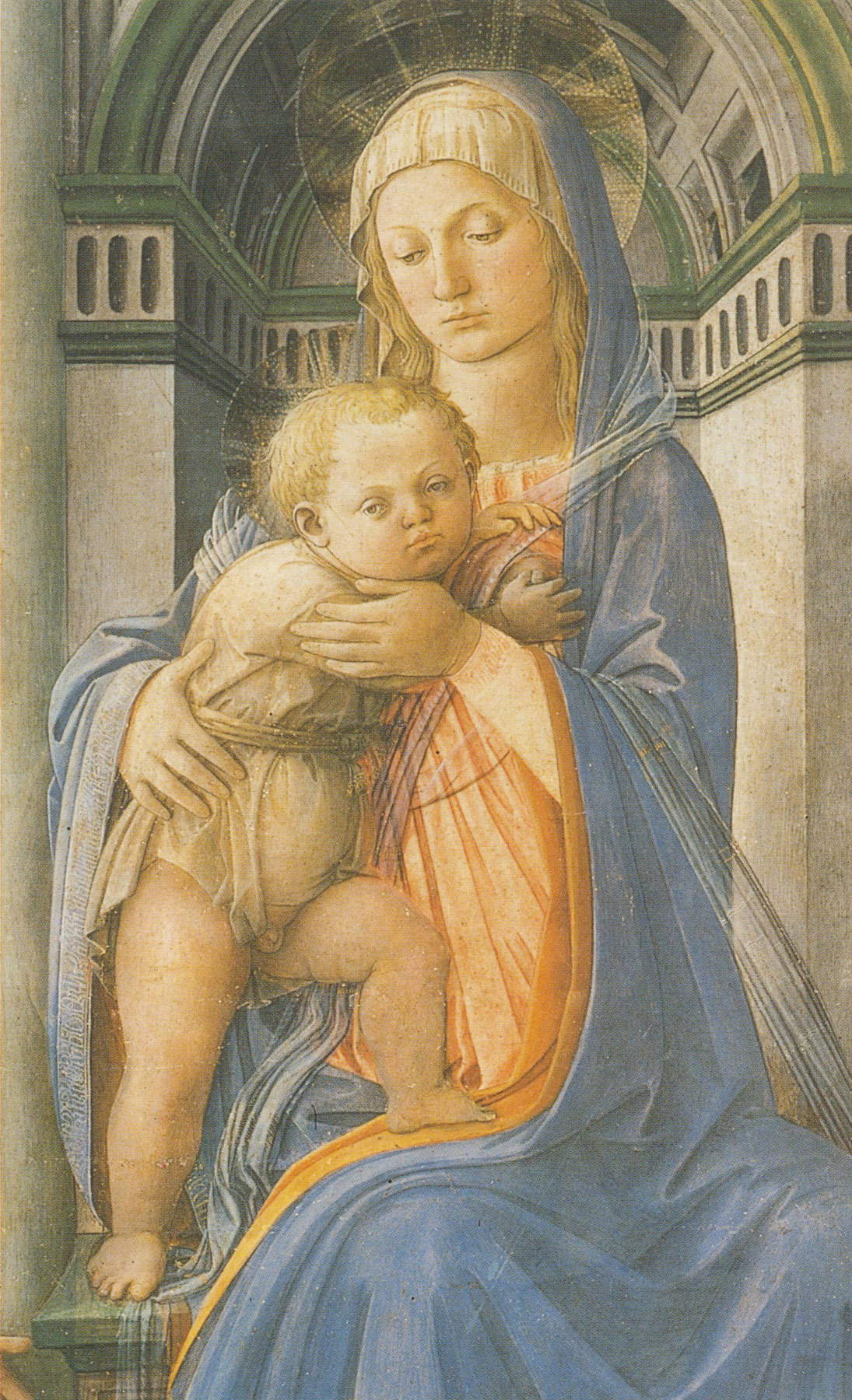

I have expressed on more than one occasion the partial reasons for my disagreement with an exhibition that also had great merits, comparing works of the highest level dispersed throughout the world3; and it is not my intention to belittle what was a good overall work by attacking certain partial aspects separately, as if each of these were the center of the enterprise. Nonetheless, it seems to me that it is appropriate to propose individual insights, precisely to bring further life to what has been elaborated and offered for debate. Therefore, I would like to give a positive follow-up to my reflections starting precisely from that front cover I quoted above, namely the panel with the Madonna and Child preserved in the Gemäldegalerie of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin4, known as Madonna 104 A. This is a painting that in my opinion could fully represent Sandro Botticelli’s contribution within the workshop, on a par with other nuclei (all however circumscribed) referable to Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Piermatteo d’Amelia; to the three painters, and a few others, the exhibition grants a few fragments of the complex referred to the Verrocchioatelier , but not to Sandro, whose tangency with the workshop seems rejected.

In the Berlin painting, the clothing of the characters belongs to the repertoire proper to Andrea’s workshop, and nevertheless the image differs from the other similar works on display in the exhibition: the ornamentation is more restrained, the chromatic matter drier, but what above all characterizes the composition compared to the others is the accentuation of the affective relationship between mother and child.5

It has already been noted several times that the depiction of one of the most popular subjects in the art of the 14th-15th centuries, the Madonna and Child (looking mainly at small-scale images intended for private devotion and close viewing) is at the center of a slow process of change that takes place between the late Middle Ages and the early Renaissance: under the impetus of needs of various orders, belonging to the areas of theology and worship, of the orientations of patrons differing in social level and culture, and not forgetting the creative contribution of artists of marked personality, the figure of the Virgin stands at the center of a complex process of transformation. The submissive maiden, who at the moment of incarnation shows herself passive, or surprised and even upset by the announcement, takes on depth, especially through the accentuation of the maternal dimension. If in the large-format images the evolution is sustained mainly by the placement “on the throne,” and thus exalting the authority and sometimes the wisdom of the Madonna, the image that tends to establish a personal relationship with the viewer points above all to the feelings that bind Mary and the Child together, soliciting the participation of those concerned with explicit references to daily life. In the field pertinent to the theme addressed here, studies have thus identified a line that from some fourteenth-century acquisitions (the name of Ambrogio Lorenzetti is worth mentioning) is articulated in the early fifteenth century by the decisive contributions of Donatello and Filippo Lippi, in relation to whom it is opportune to distinguish between the composed and austere approach of the former, tending to classicize(Madonna Pazzi, to exemplify), and the latter’s propensity to load the description with accessory elements (the furnishings, the clothes, the presence of some “companions” of the two protagonists). In the essays by the editors of the catalog various insights are devoted to the role of these two masters who operated with wide success, and who not by chance were called to work outside Florence as well; yet no comprehensive consequences are drawn from this: the paintings that between the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries some scholars had confirmed or assigned to Verrocchio return to be labeled under this name, diverging from that part of the relatively recent criticism that recognized a significant role for some of the master’s collaborators. Of course, there can be no doubt of a basic homogeneity, which sees minute correspondences in the morphologies, poses and garments that characterize the characters within a series of paintings elaborated over a narrow span of years by adopting nonchalant workshop practices: worth the example of the gestural repertoire, and specifically the case of the hands, articulated according to a limited number of modules and adapted to different functions; these are formulas exemplified on models made of poor material (the use of which is well documented), and must be read as expedients made available to the collaborators to shorten the time of execution; improper to grasp a stylistic depth in them, as sometimes occurs in the essays and cards in the catalog cited above.6

|

| Sandro Botticelli? (attributed to Verrocchio), Madonna and Child (1468-1470; tempera and oil on panel, 75.8 x 54.6 cm; Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, no. 104 A) |

|

| Andrea del Verrocchio, Madonna and Child Blessing (c. 1470; terracotta, 87 x 67 cm;. Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child (Madonna of Tarquinia), detail (dated 1437; tempera on panel, 151 x 66 cm; Rome, Galleria Nazionale dArte Antica, Palazzo Barberini) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Holy Conversation (Altarpiece of the Chapel of the Novitiate of Santa Croce), detail (1440-1445; tempera on panel, 196 x 196 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Filippo Lippi, Madonna and Child with Two Angels, detail (1460-1465; tempera on panel, 95x63 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Adoration of the Magi, detail (1475; tempera on panel, 111 x 134 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

This does not exclude that subtle variations are also found among the group’s components, and on this occasion I would like to try to point out at least one of the most significant ones.

The Madonnas of the “Verrocchio” area depicted in the panels distributed among Berlin, London, New York, Paris, Frankfurt, and Washington (to mention only the most important ones), involve a composition of static layout: standing or seated, in a frontal or three-quarter view, the Virgin either welcomes her child on her lap or displays him standing on a windowsill. In this second option, which is the most common, the Child is not an infant, but a small deity aware of his role, and he advances in the foreground with a benevolent face, raising a blessing hand. This is a pattern adhering to the model provided by the workshop leader, namely the Bargello’s fictile Madonna; a work of the highest quality, in which, despite the surface losses, the material is worked insistently and deeply, through the action of a gesture that is both rough and sure at the same time. So far, in my view, from the slow, meticulous and patient drafting that can be glimpsed behind the distilled chromatic mixtures adopted in the paintings: the curled veils of the hairstyles, the gems and pearls of the studs and borders, the laminations of the brocades, the blond and tawny hair framing the faces: testimonies to the highest style and skillful techniques within a shared program. Among the clues that have not been adequately evaluated, I point out in panel 104 A the child who, with an emotionally charged gesture, turns to his mother, stretching out his arms; the divine group, enlarged in size to the detriment of a somewhat approximate landscape, turns out to be all hinged on the intersection between Mary’s lowered gaze on her son and the embrace for which the Christ child seems to be preparing. Yet Botticelli’s Madonna in the Capodimonte Museum (which, although included in the exhibition, remained substantially defiladed from the whole), offered an opportunity to grasp the articulation of the relationship between the Berlin solution and Filippo Lippi’s more celebrated models hinging on the physical contact between mother and child: the plump putto of the Tarquinia Madonna, which interprets perhaps with a thread of irony an illustrious Donatello model; the Child of the Medici Palace Madonna, who presses his cheek to that of his mother; the aggressive climbing of the son on his mother’s body in the altarpiece of the Novitiate Chapel in Santa Croce, to which is added the timely matching of the Child with outstretched arms in the Munich Madonna. The Catalogue repeatedly mentions Fra’ Filippo, paying particular attention to the Virgin’s hairstyle in which veil scarves, headbands and locks of hair are entwined; but the frequent references to the Carmelite’s exempla were not enough to positively assess the direct presence in the workshop of a “strong” exponent of Lippesque culture.

The panel of Sandro preserved in Capodimonte, on the other hand, is revealing, since it is not an isolated case, but rather part of a Botticellian series in which, around the Madonna and the Christ child, a small group of angels-boys7 act; works that must have procured the painter an easy and immediate success in the years 1465-75, and that are linked to the magisterium of Fra’ Filippo. I recall, among Lippi’s solutions, the Madonna Trivulzio, an enigmatic gathering of commoners-children surrounding the Madonna seated on the ground, but above all the most cultivated outcome of a long series, namely the Madonna today in the Uffizi, where an elegantly dressed mother, composed and silent, is accompanied by two angels, one barely finding space and looking out from the planes behind, the other definitely the protagonist, and depicted in an advanced position as she lifts the heavy body of the putto up to bring it toward her mother, “within kissing distance.” A happy choice by Lippi, for the mischievous face that turns sharply and stares intently at the viewer is a pointed testimony to an illustrious custom of visual language. It is difficult, and perhaps vain, to trace its origin, but the fact remains that in the early fifteenth century the liveliest geniuses gave depth to their compositions by resorting to a conduit between the center of the image and the outside world, that is, between the characters depicted and a culturally qualified patronage and audience; a formulation that Leon Battista Alberti acutely summarizes in the second Book Della Pittura with singular to effectiveness: “And it pleases me to be in history someone who admonishes or teaches us what is done therein... ”8. Alberti’s suggestion gives depth to the figural formula constituted by a character who connects the interior of the image with the exterior: a sort of “voice-over” to which the most gifted masters resorted, and which was well known in Verrocchio’s sphere, as can be exemplified by citing the Saint Benedict situated in the foreground of Bartolomeo della Gatta’sAssumption of the Virgin9 . Botticelli will introduce him in theAdoration of the Magi 10, and also Leonardo in the first version of the Virgin of the Rocks (Louvre), a work still imbued with Florentine culture that qualifies the artist at the time of his appearance in Milan: here the attention of the concerning is attracted in the first instance by the unprecedented setting, which was meant to be worth arousing curiosity and wonder, but the more attentive observer picks up the call of the Angel, his gaze drawing us into the painting, among the grasses and rocks, and peremptorily inviting us to continue in the vision with his hand with his index finger pointing11.

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Madonna and Child with an Angel (1465-1470; tempera on panel, 110 x 70 cm; Ajaccio, Fesch Museum) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Madonna and Child with an Angel (c. 1470; tempera on panel, 70 x 48 cm; London, National Gallery) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli? (attributed to Verrocchio), Madonna and Child (Madonna of the Cherries) (1465-1470; tempera on canvas, transferred from original panel, 66 x 48.2 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum) |

|

| Perugino? (attributed to Verrocchio), Madonna and Child Blessing, detail (1470-75; tempera on panel, 75.8x47.9 cm; Berlin, Gemäldegalerie, no. 108) |

I return to Sandro Botticelli and the sequence of related images that unravels from the highly refined solution in the Fesch Museum in Ajaccio, having a following in the paintings of Strasbourg, Angers, and London,12 on which countless workshop replicas depend; Sandro takes hold of the formula elaborated by his master, and from the outset accentuates its “light,” almost playful character, given the young age of those gathered at a conference to read or make music: this will be the case in the subsequent summits of the type, the two famous Tondi of the Magnificat and the Pomegranate. This is an alternative choice to that of the opposite sign that spreads in parallel, and which sees lying on the Virgin’s lap the sleeping Child in which the lifeless body of the deposed Christ emerges in transparency. Moreover, in Botticelli’s early works there is no trace of melancholy, but rather a kind of familiar approach with serene women and smiling children: reassuring personifications of divinity. This is the reason why I believe another painting belonging to the Verrocchio area that was not in the Palazzo Strozzi exhibition can also be juxtaposed with Sandro’s name: the Madonna of the Cherries from the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Clothed in forms similar to those that appear in panel 104 A, the Virgin here responds to the typology proposed by Verrocchio in the sculpture; standing behind a windowsill where the Child appears, she barely touches him with her “veiled” fingers, and both again occupy a large part of the available space. The putto, however, has a shy air compared to the series as a whole; and reinforcing the intimate tone of the image are the objects placed almost casually on the balustrade: not a flap of the cloak, a precious cushion or a book of hours as in the other related paintings, but rather fragile objects removed from their usual symbolic function or the need to measure the size and foreshortening of the marble slab: a barely withered rose and three cherries standing out from the branch, objects in themselves slight in matter and meaning, just as tender are the flesh of the Child who faces us with a hesitant attitude. Completely absent are the imperceptible tips of sophisticated affectation that surface in the panels hypothetically connected to the interventions of Perugino and Domenico Ghirlandaio.

Drawing the threads of what has been said so far, I return to the underlying issues, namely the hypotheses of Verrocchio’s activity as a painter (not as a master craftsman supplying schemes and drawings, but as an executor in his own right of panels and frescoes), and of Botticelli’s concrete contribution to the activity of Andrea’satelier in the late 1960s, presented in the catalog as improbable or explicitly rejected.13 I summarize arguments that have already been expressed by critics and that I have recently suggested should be subjected to new scrutiny.

One decisive fact cannot be doubted, namely, the explicit testimony of Leonardo’s youthful writings, which debate in a friendly form with Botticelli and not with other fellow workers: Sandro must have been acting within Andrea’s workshop, and offering explicit evidence of an orientation and action that manifested itself through direct contact.

The issue of the Fortezza now preserved in the Uffizi: although it was Tommaso Soderini who diverted to Botticelli one of the Virtues already commissioned from Pollaiolo by the Mercatanzia, it seems hard to ignore some decisive facts: the interpretation of Botticelli’s solution in a Verrocchio key (unanimously acknowledged by the relevant literature), Andrea’s documented claim to a role in the affair, and the presence of drawings by the same that have been unexpectedly underestimated14.

Finally, an emblematic case, that of the altarpiece now in Budapest (Szépmüvészeti Museum): a work of painting of considerable importance destined for the nuns of the Florentine church of San Domenico del Maglio, which Andrea (repeatedly reported as the author by the sources) entrusted to the execution of a mid-level artist such as Biagio d’Antonio. The case of Biagio, a keen observer of what was being produced in the Verrocchio sphere,15 also seems to be reflected in the activity of another artist to whom the exhibition paid scant attention, Francesco Botticini, the author of a series of challenging panels in which stylistic features and typologies of the outspoken Verrocchio-Botticellian brand are employed; difficult to think that Andrea did not play a role in this respect as well,16 and that the Botticini-Botticelli encounter, as well as the Botticelli-Leonardo custom, occurred in a different place from Andrea’s workshop and in different years than those belonging to the decade 1460-147017.

In view of what I have tried to point out, I think it is appropriate to recognize Verrocchio as a complex personality, in whom coexisted the brilliant sculptor/designer, prone to experimentation, and the shrewd entrepreneur, adept atsecuring the collaboration of the brightest young people, but also in employing conscientious professionals, capable of providing images of a traditional slant and yet unexceptionable in terms of the quality of materials and workmanship. Some paintings are still waiting to be properly qualified as an important part of that area, and especially some drawings.

|

| Clockwise: Sandro Botticelli? (attributed to Verrocchio), Madonna and Child (Madonna of the Cherries), detail (1465-1470; tempera on canvas, transferred from the original panel, 66 x 48.2 cm; New York, Metropolitan Museum), Sandro Botticelli, Madonna and Child with Angels, detail (c. 1468; tempera on panel, 100 x 71 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte), Francesco Botticini, The Three Archangels, detail (1470-1475; tempera on panel, 135 x 154 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery), Sandro Botticelli, Fortress, detail (1470; tempera on panel, 167 x 87 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli, Madonna and Child with Angels (c. 1468; tempera on panel, 100 x 71 cm; Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte) |

|

| Sandro Botticelli? (attributed to Verrocchio), Madonna and Child with Angels (Madonna of Milk) (c. 1470; tempera on panel, 96.5 x 70.5 cm; London, National Gallery) |

In the Florence of the early Medici, and in the years of Piero and the young Lorenzo, when the economic and political crisis was still latent, some data gleaned from historical-documentary research and the evidence related to the exercise of artistic activity offer a sufficiently clear outline of the situation, at least as far as figurative culture is concerned: there were two major centers of production, and between the two there was an explicit difference in approach. In the spheres directed by Antonio and Piero Pollaiolo, to whom we owe progenitor works and overall homogeneous programs, the authority of the master overrides the intervention of the collaborators; in Verrocchio’s workshop, the more fluid structure of the ’staff included apprentices of varying caliber but also growing personalities close to establishing an autonomous activity: life must have been much more eventful, the overlaps, collaborations and exchanges very frequent among those who worked closely together. Difficult, sometimes impossible, to decipher in definitive terms the individual skills.

This is ultimately responsible for the different course of the two critical events: relatively regular one concerning the sons of the poulterer Benci, where the main reason for contrast between the various critics arose from the difficulty of distinguishing Antonio’s direct appurtenances from Piero’s, and from the need to circumscribe the rare cases of collaboration between the two; while in that relating to Andrea di Cione the multiple divergences of opinion arose from the variety of collaborators and the varying length of their tenure in the workshop; a situation that betrays an entrepreneurial approach of a “modern” slant, and that eludes capillary reconstruction. And again from this, the persistence of questions. I mention what is perhaps the most disturbing knot, and still highly problematic, to which the Florentine exhibition did not give space: the short series of drawings in the Uffizi related to the area of that burlesque culture that is documented above all in the literary sphere, but which must have had echoes in the figurative language of graphics and in forms of entertainment hinging on the theme of grotesque deformation18. In the rare traces that are preserved of all this, critics have evoked engravings from the Nordic area and (not surprisingly) the names of Verrocchio and Pollaiolo, Botticelli and Leonardo, though without dissolving the many doubts.

Notes

1 - Verrocchio, Leonardo’s Master, exhibition catalog (Florence 2019), edited by Francesco Caglioti and Andrea De Marchi, Florence-Venice 2019.

2 - Giorgio Vasari, The Lives, ed. edited by Paola Barocchi and Rosanna Bettarini, Florence 1966-1987: III (text), pp.533-545; IV (text), pp.15-38.

3 - Gigetta Dalli Regoli in Finestre Sull’Arte online 2019; Eadem, Verrocchio, Leonardo’s Master. Postilla, in Art Criticism, n.s. (2019), 1, forthcoming.

4 - Catalogue 2019 cit., pp.49 ff, and pp.120-122.

5 - In the impossibility of introducing here the bibliography relevant to the developments of the Marian cult, for a proper consideration of the problem I cite Hans Belting, Il culto delle immagini [1990], Rome 2001. I have addressed the subject more than once, but I do not consider it appropriate to burden this text with references that are not strictly necessary.

6 - In the Catalogue there is at times a certain verbal redundancy, which accumulates suggestions of a literary slant around elements that would suggest a composed adherence to technical-craft data. Just one example: regarding the hands articulated according to formulas exemplified on earth or stucco models, employed for right and reverse in different paintings, it is astonishing to read in the file devoted to the Berlin Madonna “the contrivance of snap hands on quivering wrists” (Catalogue 2019, cit., p.120).

7 - Gigetta Dalli Regoli, I garzoni di Sandro in Critica d’arte, 37-38 (2009), pp.41-48.

8 - I recommend the recent text by Stefania Macioce, When Painting Speaks. Gestural and sound rhetorics in art, Rome 2018. I have proposed some clarifications related to Alberti’s text in a short paper (Gigetta Dalli Regoli, Gli obiettivi del De Pictura, fra cultura delle corti, ideologia borghese-mercantile e precettistica in Schifanoia, 30-31 (2006), pp.47-61).

9 - St. Benedict originally, later transformed into St. Filippo Benizzi: see Cecilia Martelli’s timely entry, Catalogo 2019, cit., p.158.

10 - This is the character on the far right cloaked in yellow, identified as a self-portrait of the painter.

11 - On the events of the work I refer to Pietro C. Marani, Leonardo, una carriera di pittore, Milan 2003, pp. 137-139. For the theme of the internal/external relationship in the image I point to the fundamental texts by Ernst H. Gombrich, The Image and the Eye [1982], Turin 1985, and David Freedberg, The Power of Images [1989], Turin 1993.

12 - Andrea De Marchi, Catalogo 2019, cit., p.76: “mysterious painting whose major affinities with the youthful group of the young Botticelli should be emphasized.” I do not think who this is a mystery, but rather an incongruous attribution, which should move from Verrocchio to Botticelli. Exactly.

13 - Andrea De Marchi, Catalogue 20019, cit. p.57.

14 - I discussed this in I garzoni di Sandro, 2009, cit, pp.46-47, and in Finestre sull’Arte on line, 2019, cit.

15 - Dario A. Covi, Andrea del Verrocchio. Life and Work, Florence 2005, pp. 192-197; on Biagio’s relationship with Verrocchio’s sphere, see Roberta Bartoli, Biagio d’Antonio, Milan 1999, pp. 31 ff.

16 - For a consideration of the connection with Verrocchio’s circle, I refer to the analysis of the late Lisa Venturini(Francesco Botticini, Florence 1994, pp. 108-109): works such as The Three Archangels (Uffizi) and such as Saint Monica and the Augustinian Nuns (Florence, Church of Santo Spirito), would have introduced some disturbance into the “Panverrochio” picture presented in the exhibition.

17 - A re-examination of the relationship between Botticelli and Botticini does not seem to appear in the very recent volume Botticelli. Past and Present, edited by Ana Debenedetti and Caroline Elam, London 2019.

18 - Gianvittorio Dillon in Anna Maria Petrioli Tofani (ed.), Il Disegno fiorentino del tempo di Lorenzo il Magnifico, exhibition catalog (Florence, Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe, from April 8 to July 5, 1992), Milan 1992, pp.120-125; Michael Kwakkelstein, Botticelli, Leonardo and a Morris Dance in Print Quarterly, 15, 1 (1998), pp.3-14; Gigetta Dalli Regoli, La Fuggitiva, a Young Woman on the Run in Art Criticism, 29-31 (2007), pp.7-59 (pp.49-51). A reconsideration of the relevant set of drawings and prints, is in Bert W. Meijer (ed.), Florence and the Ancient Netherlands, 1430-1530, dialogues between artists, exhibition catalog (Florence, Galleria Palatina, June 20 to October 26, 2008), Florence 2008, pp.132-137 (entries by Paula Nuttal).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.