How did people go to spas in the Middle Ages? Those curious to derive information about ancient spa treatments might peruse a valuable codex preserved at the Angelica Library in Rome, a poem by Pietro da Eboli (Eboli, c. 1150- c. 1220) entitled De Balneis Terra e Laboris (“The Baths of the Land of Labor”), but better known as De Balneis Puteolanis (“The Baths of Pozzuoli”). Written in the thirteenth century, it consists of thirty-five epigrams of six couplets each (although in the 1474 manuscript in the Angelica Library only eighteen are counted), and it was particularly popular because as many as twenty-one witnesses are known and, centuries later, several printed editions (twelve, appearing between 1475 and 1607) were also derived from it: the manuscript of the Angelica, which belonged in the eighteenth century to Mario Guidarelli and came to its present place of preservation with the library of Abbot Domenico Passionei, is, however, the oldest witness of Pietro da Eboli’s work, of which we do not preserve the original written by the poet, and was produced in the 1450s by a Neapolitan workshop evidently specialized in the production of luxury manuscripts, given the magnificence of the illustrations accompanying the poem.

We find ourselves, then, at the time of Manfred, son of Frederick II, who, according to the chronicler Riccardo di Sangermano, in the late summer of 1227, as he was about to leave Otranto for a journey to the Holy Land, was allegedly forced to postpone the trip because of the spread of an epidemic, which caused him to change his intentions: “Imperator,” Sangermano writes in his Chronica, “de Apulia tunc venit ad balnea Puteoli,” or “The emperor from Apulia left for the baths of Pozzuoli,” although the text does not add more about the reasons why Frederick II changed his initial plans to reach the Puteolian baths. Frederick II, moreover, is, according to many scholars, the dedicatee of De Balneis Puteolanis, since the work is composed “Cesaris ad laudem,” that is, “in praise of Caesar,” although we do not know for sure who the emperor the poem was intended to praise was. However, it is certain that, scholar Salvatore Sansone has written, the poem “celebrated, through the medium of a literary work, the worship of antiquity and the antiquarian suggestion that the baths of Pozzuoli bore witness to, along with what was the classical practice of thermal bathing.”

If, after the fall of theRoman Empire, spa facilities throughout Europe had fallen into disrepair, in some areas, especially in southern Italy, there is evidence that the habit of bathing did not decline: however, between the 12th and 13th centuries there was a renewed and widespread interest in this activity widely in use among the Romans, an interest that brought the practice of bathing back into vogue in Pozzuoli. “The interest in the baths that emerged in Italy between the 12th and 13th centuries,” Massimo Danzi has written, “also reproposed, with the medicalization of the waters, the notion of ’pleasure’ as a ’cure of the soul.’ And if it is true that the Middle Ages had loaded the waters, already a symbol of purification in the pre-Christian Judaic and Roman tradition, with sacred cloths making it a source of life and a figure of God as the sacrament of baptism says, equally concrete is the transformation of the ’baptismal font’ into a ’fountain of youth’ and then into a profane ’garden of delights’ evidenced by a rich iconography between the Middle Ages and the civilization of the courts.”

The area of the Phlegraean Fields was well known even in antiquity for the properties curative properties of its thermal waters of volcanic origin (the same ancient name for Pozzuoli, Puteoli, comes from the word putei, or “wells,” those from which the waters flowed), and the poem by Pietro da Eboli lists all the ancient baths describing the benefits that their waters could bring to the body of those who bathed, but also simply evoking the pleasant moments that could be spent at the baths. Exactly as today, then, people went to the baths to cure their ailments, but the baths could also be an opportunity for recreation. Here, then, the Balneum quod sulphetara dicitur was suitable for making women fertile, the Balneum Juncara was believed to cure depression by nourishing the spirits, giving cheerfulness and banishing worrisome thoughts from the mind, the Balneolum was instead considered suitable for any ailment (and in particular for the head, stomach and kidneys, moreover it was thought to have antipyretic, able to calm fever), the Balneum Calatura was suitable for those with lung diseases, or coughs and rheumatism, the Balneum Tripergulae for stomach problems, and again the Salviana bath was instead useful for women. There was also a bath reserved for the clergy, the Fons Episcopi, moreover capable of healing pellagra.

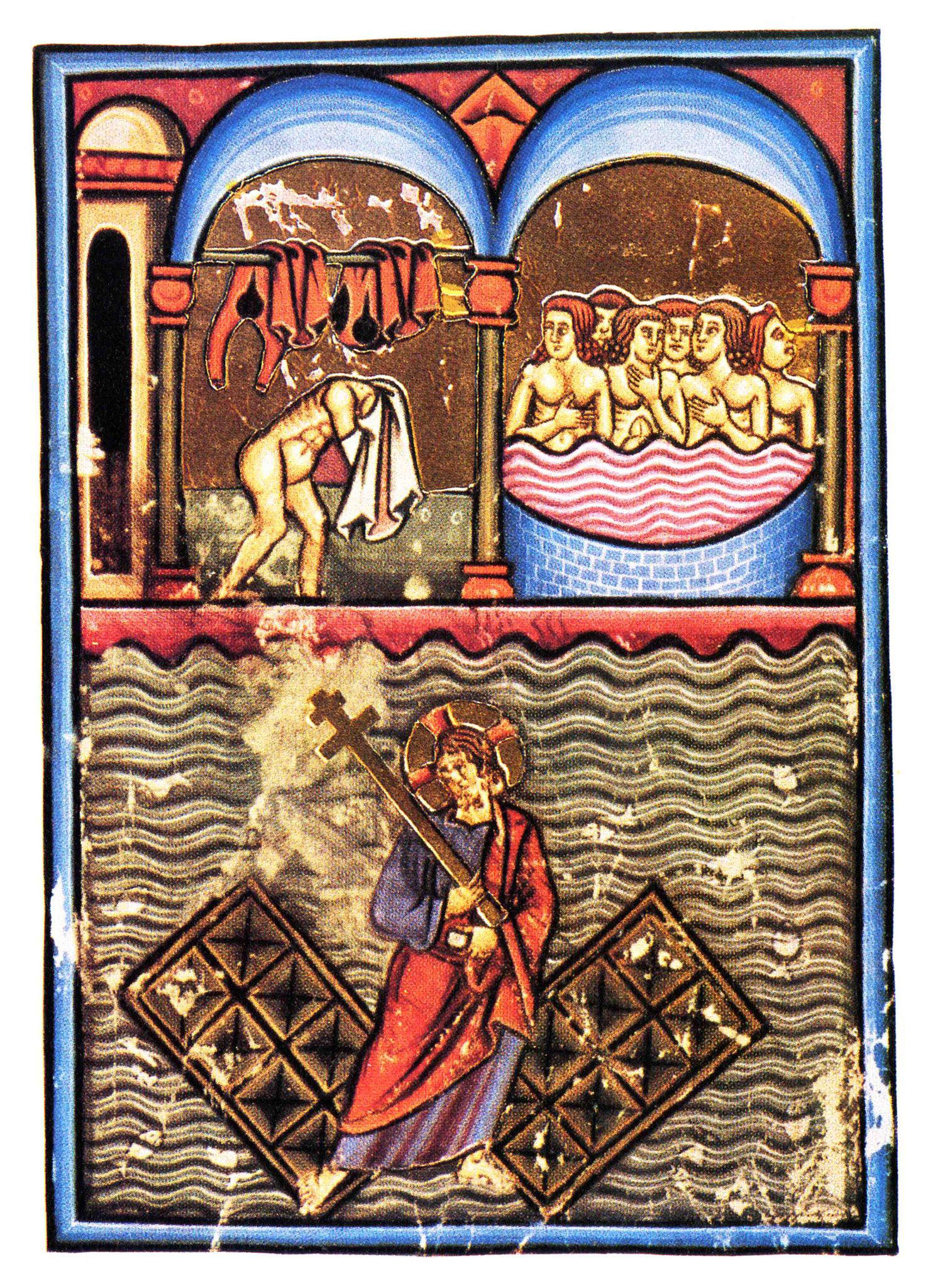

It is interesting to note how the notions of De Balneis Puteolanis represent a kind of mixture of ancient medical techniques (although Pietro da Eboli did not consider himself a doctor, and did not belong in any way to the famous Salerno Medical School, which, on the contrary, did not seem to consider the beneficial properties of thermal waters particularly important) and popular beliefs: in composing his epigrams, wrote the literary historian Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli, Pietro da Eboli "welds himself to the legends of Virgil’s magical Naples or those that in popular devotion had folklorically mutated the Sudatorium of San Germano into the entrance to Purgatory and the Balneum Tripergula, near Lake Avernus, into the place where Christ had broken the gates of hell. Thus, the envy of the Salerno physicians for those miraculous water cures is not without reason: the ’baths’ of Pozzuoli were free and open to all, and the archiatres of thehyppocratic civitas would have lost in profit. De Balneis Puteolanis celebrates a greatness still recorded with all the excitement by the ’vulgar’ Chronicle of Partenope in the 15th century. The illustrations of the codex take us back into the beneficent heats of that medical universe; from this sensibility is formed the extraordinary episode of culture and intellectual renewal typical of the time of Frederick II."

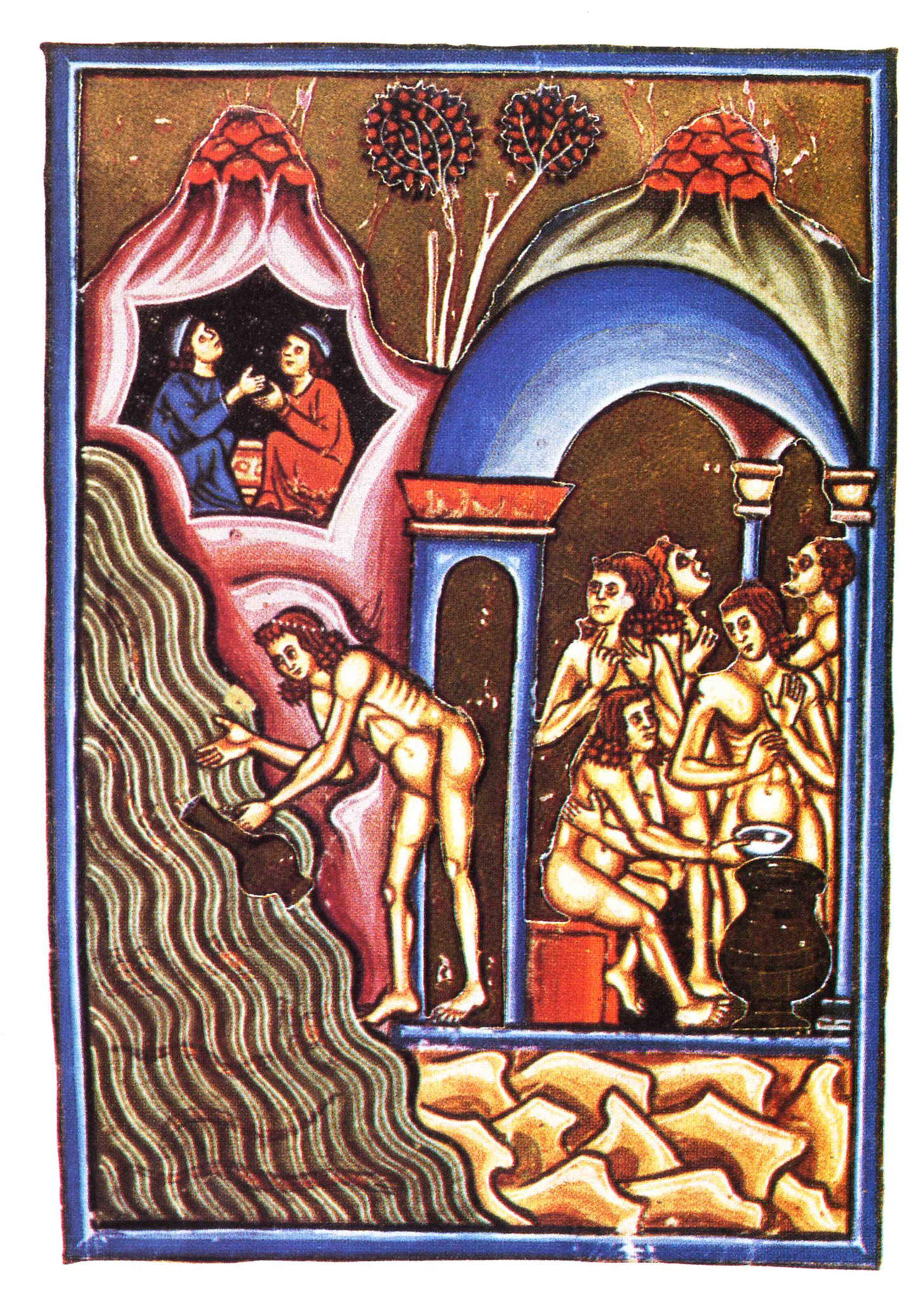

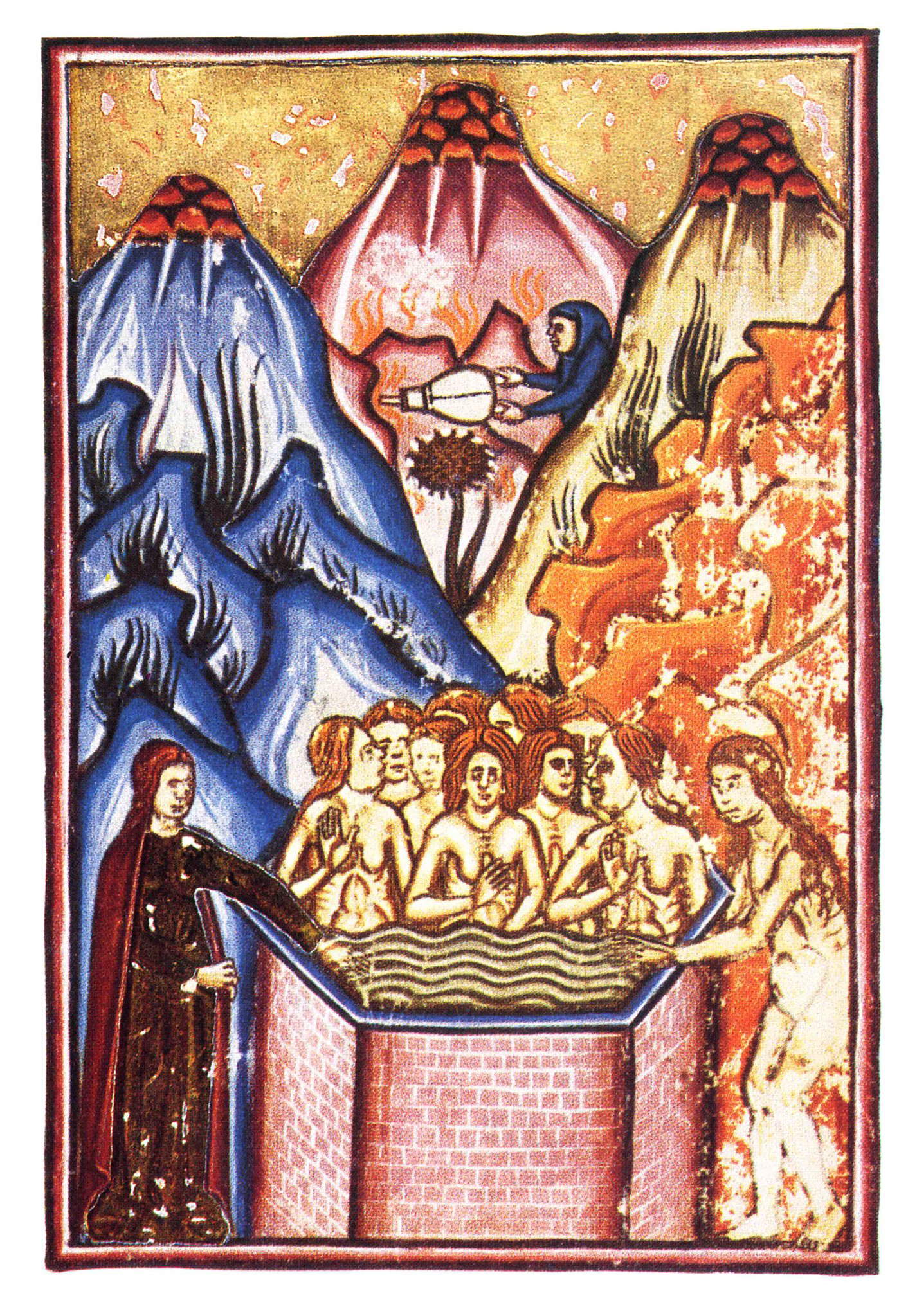

The 1474 manuscript of the Angelica is richly endowed with illustrations, miniatures executed by a single artist, enclosed within blue, green and red frames, and featuring backgrounds executed in gold leaf. Because of the richness of the decorations, the manuscript stands out as one of the main examples of miniatures from 13th-century southern Italy, with scenes that moreover are described vividly and with marked narrative taste (although the figures know few variations), and that blend Byzantine elements with Roman and Oriental architecture. From the illustrations, moreover, we are able to get an idea of how people frequented the Baths of Pozzuoli in ancient times (which, moreover, were free): the Sudatorium, for example, was a small domed building that we can think of as a kind of sauna, since here one did not bathe, but entered to sweat (in the illustration, however, we also see a personage intent on collecting water from the spring with a cup), and it was equipped with crypts ubi hospitantur infirmi, that is, small caves equipped with beds to accommodate the sick. Beneficial water was applied to the part of the body that was to be healed: we see this in the illustration accompanying the epigram De balneo quod bulla nuncupatur, about a bath whose waters were believed to be beneficial for the head and eyesight, and indeed the characters in the miniature bathe these areas of the body. In any case, in general in order to benefit from the properties of the waters it was necessary to bathe, and this was done completely naked, and in company, as the images in De Balneis Puteolanis attest: going to the baths thus also became a social practice as it was in ancient Rome, and from the time when the poem by Pietro da Eboli was composed (the first text to give an extensive and detailed account of the resurgence of interest in thermal baths), the use of attending baths would become more and more widespread, especially in northern Europe.

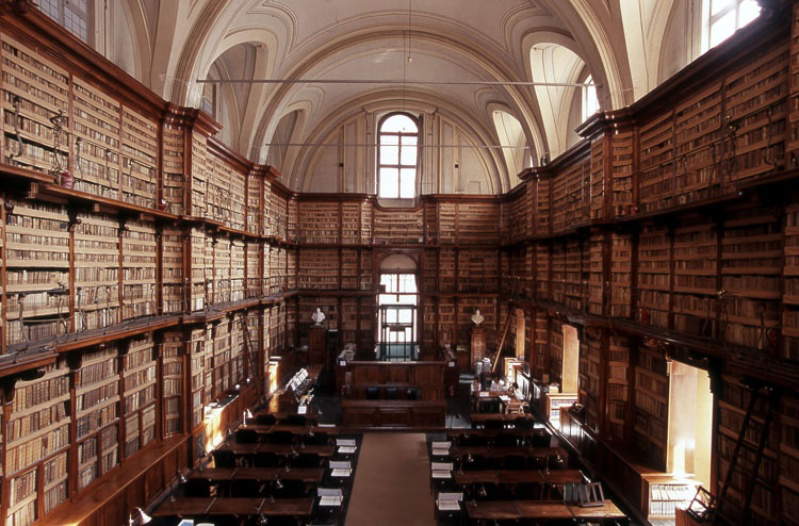

Founded in 1604 by the Augustinian bishop Angelo Rocca (Rocca Contrada, 1545 - Rome, 1620), from whom it takes its name, the Angelica Library in Rome boasts an interesting record: it is in fact the first library open to the public in Rome as well as, along with the Ambrosiana in Milan and the Bodleian Library in Oxford, one of the first in Europe, since it was founded with the intention of sharing the books in its possession with the community of readers. It has been under the Ministry of Culture since 1975. The Angelica Library has an ancient collection of about 120,000 volumes (out of a total of about 200,000 books it holds), and it specializes mainly in the history of the Reformation and that of the Counter-Reformation. Then the important nucleus of works devoted to the thought of St. Augustine and the activity of the Augustinian order stands out, and also worth mentioning are its collections of volumes on Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, its conspicuous manuscript collection (2,700 volumes and 24,000 scuolti documents), its many incunabula (1,100 editions), and its large number of cinquecentine (about twenty thousand).

The De Balneis Puteolanis is one of the most valuable treasures preserved here, but at least the Liber memorialis from Remiremont Abbey (a manuscript dating back to the 9th century), a 14th-century codex containing an illustrated version of the Divine Comedy, a 14th-century Flemish Book of Hours, and the incunabulum of the De oratore, or the first book printed in Italy (it came to light in the Subiaco printing works, it was running in 1465) are worth mentioning. The Angelica also preserves a copy of the first printed edition of Dante’s Commedia, published in 1472 in Foligno. Finally, worth mentioning is the collection of the Literary Academy of Arcadia, consisting of about 4,000 volumes and received by the Angelica in 1940: it preserves printed volumes, 41 manuscripts and autograph letters of the Arcadians.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.