Today, as is well known, one of mankind’s great problems is global warming, a consequence of climate change: average temperatures continue to rise year after year, partly due to anthropogenic activities, and if something is not done to limit the damage, the risks become greater and greater. But in the history of human beings there was also a period when the problem was the opposite: a very long period for humans, since we are talking about an epoch that goes roughly from the beginning of the 14th century to the middle of the 19th century, but it is nothing when compared to geological eras. In the history of climatology this period is known as the "Little Ice Age," and it was characterized by a sharp drop in temperatures, especially in the Northern Hemisphere, the advance of glaciers (which reached their maximum documented extent: new ones were also formed), frequent snowfall, freezing streams, and ruined crops, so much so that several famines occurred during the coldest winters.

During this period (between 1309 and 1814, to be exact), the waters of the Thames in London froze twenty-three times, and on five of these occasions it was planned to organizing fairs on the frozen river. The ice sheet, in fact, was so thick that it was possible to set up stalls, tents and markets on the surface of the Thames, and it was an entirely unusual sight, documented by the painters and illustrators of the time. So-called Frost Fairs (literally “frost fairs”) were rare events, held whenever the waters of the river froze enough to allow them to be set up, and, of course, whenever socio-economic conditions permitted them (in the years of Puritanism, for example, events such as Frost Fairs were not looked upon favorably, and no fairs were recorded even during years of economic crisis, despite the fact that there were suitable weather conditions): the first was that of 1608, which was followed by those of 1683-1684 (i.e., the coldest winter ever experienced in England), 1716, 1739-1740, 1789 and 1814 (and if one wishes, one can also add a very first fair in the year 695, although very little is known about this occasion). It should be specified that the Thames between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries was not the same as it is today: the course of the river at that time was wider and lower, so that the water flowed more slowly than it does today and made the possibility of freezing higher. Also, in ancient times London Bridge (which today has a modern appearance because it was rebuilt between 1967 and 1972: in fact, the expression Old London Bridge is used to refer to that of the time) consisted of nine arches that were barred on certain occasions, and in fact the bridge became a dam, and this allowed the water, in winter, to freeze with greater ease.

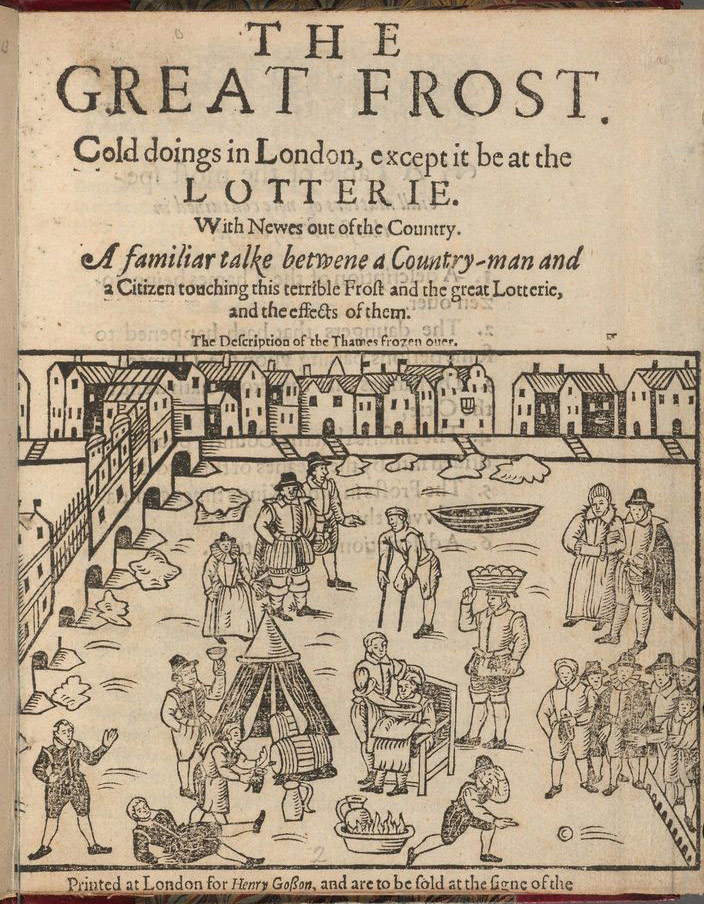

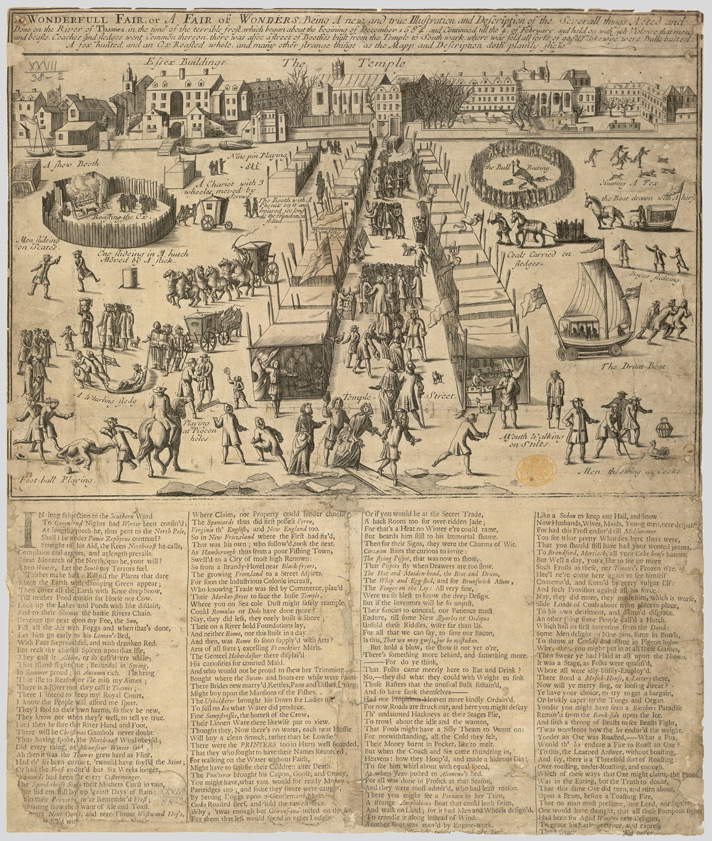

The first widely documented fair is that of the winter of 1608: as early as December 1607 the Thames was frozen enough to make it possible to walk from Southwark to the City, and by January the thickness was thick enough to hold the necessary fittings. A pamphlet was published that year, by an author unknown at the time, in which The Great Frost, or “the Great Frost,” is mentioned: it is an imaginary conversation between a citizen of London and a resident of the countryside, in which the former tells the latter everything unusual that happens in the city during the harsh winter that turns the waters of the river into ice. For example, experiencing the thrill of getting a shave from a barber directly on the Thames-a scene we also see illustrated on the cover of the pamphlet, where we notice a series of characters intent on a wide variety of activities (those who play, those who set up a tent, those who drink, those who stroll). The Frost Fairs were popular events that could be very rowdy and organized even to the limits of what was allowed, but because of their peculiarity they always saw high attendance. They were true markets: hawkers sold a wide variety of goods there, and it was also a necessity for many, because with the Thames frozen London was deprived of its outlet to the sea and so many could not take their goods out of the city, suffering considerable economic damage. But selling goods was not the only activity: an illustration from 1684 shows what one could do at that year’s Frost Fair (incidentally called the Fair of Wonders in that same print). Thus, one could play soccer (“football playing”), ride in a boat pulled by other people or horses, play bowls, skate, walk on stilts, and participate in ante litteram “barbecues” (in the upper left part one can see an enclosure dedicated to “roasting the ox” “roasting the ox”), there could be competitions in fox hunting or cock throwing, a macabre sport in vogue in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century England (a rooster was tied to a stake and then, in turn, sticks were thrown at it until it died: as early as the mid-18th century, however, politicians and journalists began to oppose this bloody practice, so much so that by the 19th century it had fallen out of use), and there was also a "printing booth " where attendees could have a personalized postcard printed as a souvenir of their visit to the fair.

|

| Illustration from the book The Great Frost (1608). |

|

| Unknown illustrator, A Wonderful Fair or a Fair of Wonders. A new and true illustration of and Description of the Several things Acted and Done on the River of Thames, in the time of the terrible frost (published 1684; engraving; London, The British Library) |

|

| Anonymous illustrator, An exact and lively mapp or representation of booths and all the varieties of showes and Humours upon the ICE on the River of Thames by London (published by William Warter in 1684; engraving, 366 x 422 mm; London, The Royal Collection Trust) |

Some paintings show us in more detail how the fair was organized. The stands were attached to each other and arranged along two neat rows, between one bank of the river and the other, somewhat like the modern Christmas markets, of which these Frost Fairs can almost be regarded as the ancestors. There people sold goods (according to a chronicle of the time there were “every imaginable commodity: clothes, dishes, pottery, meat, drinks, brandy, tobacco, and hundreds of other products that we won’t list here”), could eat or drink, and could attend entertainment shows (there were, for example, tents reserved for music): the latter, however, took place mostly on the sides of the fair, outside the spaces reserved for the stands, as can be seen from the artwork and illustrations. There is one from 1716 that is surprising in its modernity, because the merchants’ stalls are meticulously laid out in a kind of map, each marked with a letter, as in contemporary fair maps: so here is the space reserved for eighteenth-century “bowling” (called “Nine-pin playing”), here is the “printing booth,” and then again the music booth, the tavern, the gin seller’s stall, the gingerbread cookie stall, the blacksmiths’ stall.

The Frost Fair of 1683-1684 was set up between London Bridge and the Temple district, and on January 31, 1684, King Charles II also visited the event (even getting his own postcard printed!). But postcards were not the only souvenirs that visitors to the Frost Fair could take home: as in today’s Christmas markets, there were several “designer” items that could be purchased at the stands. At the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, for example, a glass mug (a “miraculous survivor,” the museum calls it: because Frost Fairs were few in number and because these objects were so fragile) is preserved on the rim of which is engraved the inscription “Bought on ye Thames ice Janu ye 17 1683/4” (“Bought on the frozen Thames on January 17, 1683/4”).

Among the works of art, the most striking one to represent the Frost Fair of 1683-1684 is probably the canvas by the Dutchman Abraham Hondius (Rotterdam, 1625 - London, 1691), who moved to London in 1666: the painting, preserved in the Museum of London, is notable for its descriptive minuteness, typical of Dutch artists of the time. In the painting, apart from the boats being pulled ashore, we see the fair in full swing: the two wings of booths in the center of the painting (plus a third row in the middle about halfway through), families strolling, horses pulling carriages on the ice, a group of people playing nine-pin behind the first stalls, boats being pulled across the ice complete with sails unfurled, and the city in the background.

|

| Unknown artist, Frost Fair on the Thames with Old London Bridge in the background (ca. 1685; oil on canvas, 64.1 x 76.8 cm; New Haven, Yale Center for British Art) |

|

| Abraham Hondius, Frost Fair on the Thames (1684; oil on canvas, 66.9 x 111.9 cm; London, Museum of London) |

|

| Unknown illustrator, Frost Fair on the Thames (1715; engraving; London, Layton Trust) |

|

| The cup-souvenir preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London |

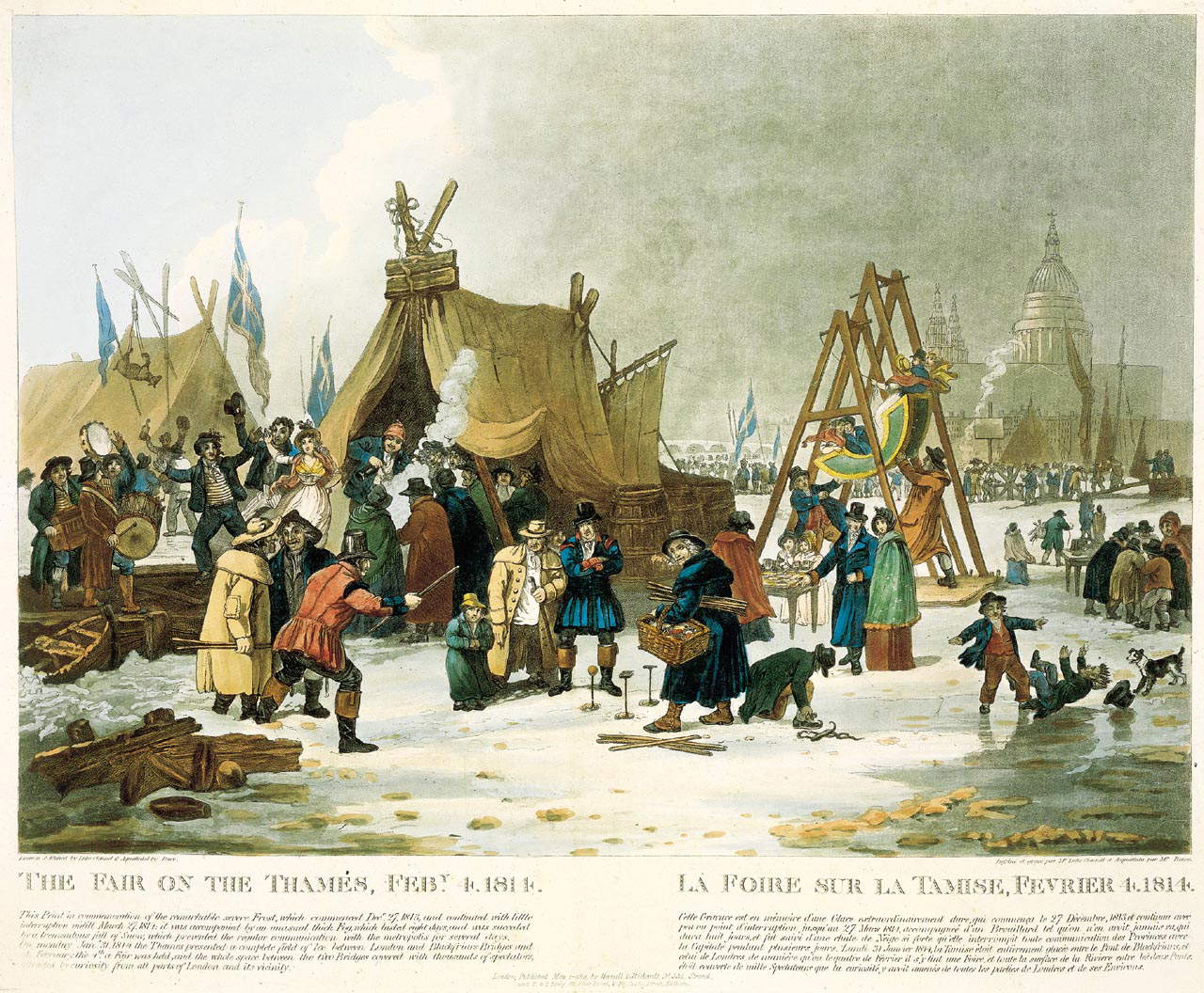

The last Frost Fair is also the most and best documented. It began on Feb. 1, 1814 (The Times, the next day, reported that “in some places the ice is several feet thick, but there are also places where it is dangerous to venture”), took place in the heart of the English capital, namely between Blackfriars Bridge and London Bridge, lasted four days, and, compared to the fairs of the past, saw the “eating” dimension prevail. There was no shortage of traditional “roasted ox,” there were stalls selling spiced beer, tea and hot chocolate, and generous cups of gin and a particular drink called “purl,” or the frost fair equivalent of the mulled wine found at traditional alpine markets: it was an alcoholic spirit made from gin and flavored wine similar to vermouth, which was served very hot. Temporary pubs were also set up among the stands (which at the 1814 fair looked more like tents: they were made from boat sails). Activities included more music, wild dancing, and games such as the stainless “nine-pin.” The 1814 edition has also gone down in history because it is the one to which perhaps the most famous anecdote of the Frost Fairs dates: an elephant was paraded across the frozen Thames near Blackfriars Bridge. After all, if the weight of the ice could support stalls, kitchens, and especially thousands of people, it could also support the passage of a pachyderm.

There were also a few incidents on that occasion: nowadays we are used to seeing markets manned by the police, but at that time this garrison was not there and a rudimentary orderly service was carried out by the Thames boatmen, who, however, could not look after everything. It thus happened that some people strayed too far from the area where the ice was thickest, and the chronicles of the time record some cases of drowning of people who went where the ice was thinnest and most fragile. These events are faithfully recorded by a printer of the time, one George Davis, who on the occasion of the 1814 Frost Fair published a booklet entitled Frostiana in which the story of the frozen Thames was told.

|

| Unknown illustrator, Frost Fair on the Thames (published February 18, 1814 by Burkitt & Hudson, London; aquatint on paper, 371 x 493 mm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Luke Clenell, Frost Fair on the Thames (published February 8, 1814; aquatint on paper, 442 x 545 mm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Anonymous illustrator, A view of Frost Fair (1814; woodcut, 349 x 454 mm; London, British Museum) |

After 1814, as mentioned above, there was no further occasion to hold other Frost Fairs, and this was for a number of reasons: the climate that began to get warmer (in January 1814 the average daily temperature in London was -2.9°, whereas today it is around 4°), the construction of a new London Bridge in 1831 that no longer allowed for the barrages of previous eras, and above all the works that affected London’s great river in the Victorian age. Indeed, the Thames was dredged and the banks raised, and with a deeper river (and its flowing faster) it is more difficult for the waters to ice over. It has happened again, however, since 1814: the last time was in the winter of 1962-1963 (numerous photos show people walking on the river, and there is one that even shows a man riding a bicycle across it at Windsor Bridge), but not enough to allow the organization of a modern Frost Fair. Not least because, that year, the river froze only superficially and not for as long as in past eras.

Today, therefore, witnessing miraculous ice fairs like those that were organized in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries is very difficult, probably impossible, partly because the river is not what it once was (its course, as it turns out, has been altered), partly because global climate warming obviously works against it, and partly because, even if one wanted to, modern safety standards are more stringent than those of three or four centuries ago. There is therefore nothing left to do but. be content to see Frost Fairs on the paintings and illustrations of the time.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.