At the Pinacoteca di Brera is preserved the oldest complete tarot deck not only in Italy, but even in the world, and the fact that it has been preserved in its entirety is an exceptional case. A testimony that is therefore extraordinary, if one considers that the entire Sola Busca deck, so named by its previous owners (the Marquise Busca and Count Sola), dates back to the 1490s. It is not, however, the oldest tout court, because the picture gallery has held, since 1971, part of another tarot deck, known as the Brambilla deck (named after the previous ownersî previous owners), made between about 1442 and 1444 by the Cremonese workshop of Bonifacio Bembo (Brescia, 1420 - Milan, 1480) for the Duke of Milan Filippo Maria Visconti, but only forty-eight cards of the total deck have come down to us: the others have been lost.

The Sola Busca deck is therefore the only complete tarot deck of seventy-eight cards dating from the Renaissance still intact. In his Memorie spettanti alla storia della calcografia, Leopoldo Cicognara (Ferrara, 1767 - Venice, 1834) in 1831 cited the “nobilissima dama sig. marchesa Busca nata duchessa Serbelloni” as the one who “graciously allowed us its diligent inspection.” Moreover, it was Cicognara who dated the Sola Busca deck to 1491: "What, however, may make our research of some importance, is what results from the observations diligently procured on a deck of Cards impressed in Venice with the permission of the Venetian Senate in the year ab urbe condita MLXX placed at the figure of Bacchus at N. XIV, which corresponds to 1491, since the Venetian Era ab urbe condita begins from the year of the Vulgar Era 421 not already in 453 as others, dealing with this subject, erroneously wrote."

|

| Nicola di mastro Antonio and anonymous illuminator, King of Swords, from the Sola Busca Tarot (78 burin engravings printed on paper pressed and glued to form a card, illuminated in color and gold, back painted in faux porphyry, 144 x 78 mm, Venice 1491; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

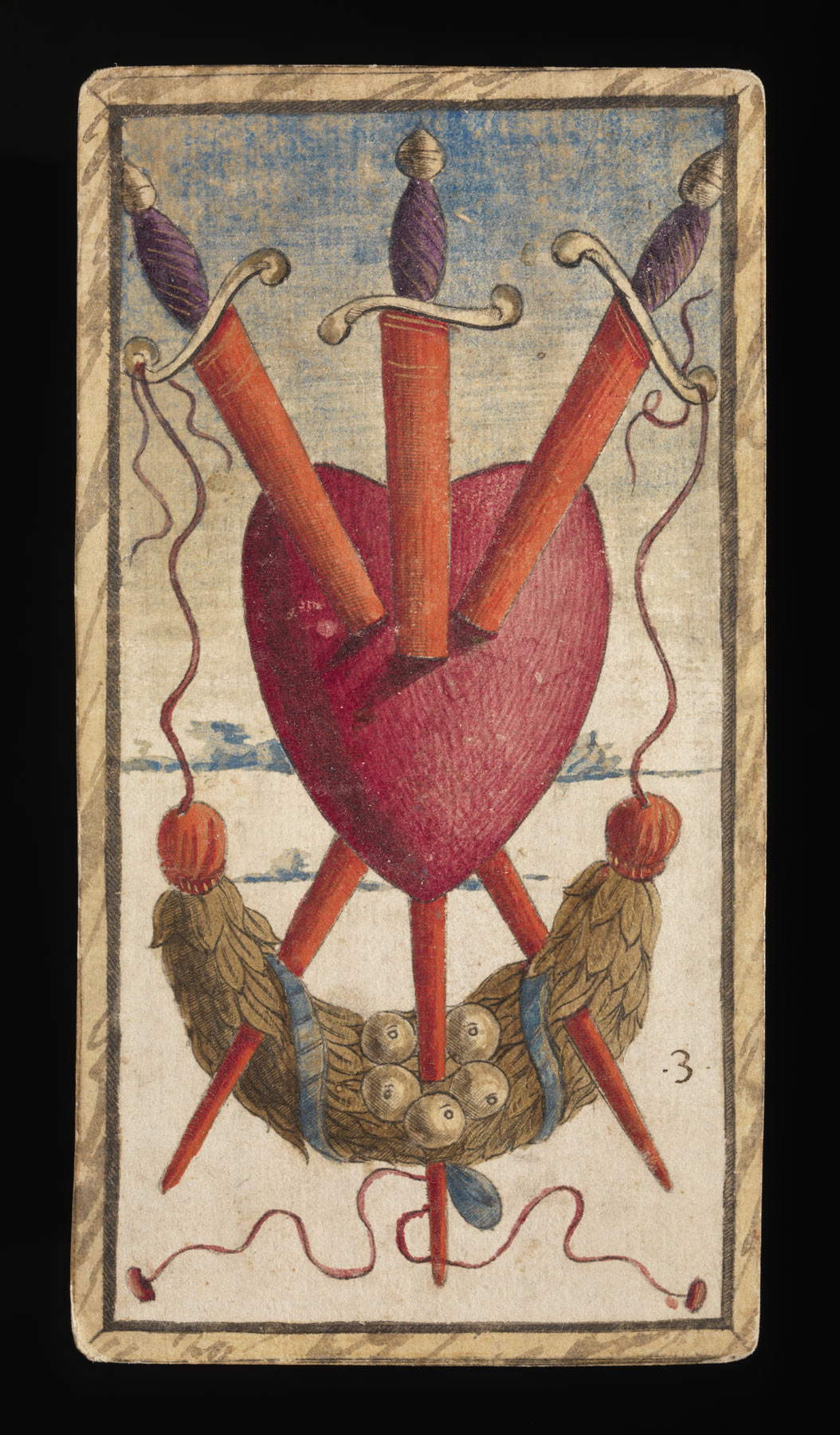

| Nicola di mastro Antonio and anonymous illuminator, Three of Swords, from the Tarot Sola Busca |

|

| Nicola di mastro Antonio and anonymous illuminator, Triumph VIII, from the Tarot Sola Busca |

Indeed, the game of tarot is attested by sources as a pastime intended for play in courts from the fifth decade of the 15th century in northern Italy, particularly in the Ferrara area: it was therefore a refined game of an intellectual kind. Today, when we think of tarot cards, we associate them with the power to foretell the future, with objects related to Kabbalah and magic, but in fact this meaning began to spread in the 18th century with the esoteric theories of Antoine Court de Gébelin: In the eighth book of the monumental text Le Monde primitif, analisé et comparé avec le monde moderne, consideré dans l’histoire civile, religieuse et allégorique du calendrier er almanach, he wrote that there was a work of the ancient Egyptians that had escaped the flames that had destroyed their libraries and that this work held their purest doctrine: a book that no one had ever attempted to decipher and that was regarded as a bunch of strange, meaningless figures. The Egyptian book of which Court de Gébelin spoke was nothing more, according to him, than the tarot, composed of 77 or 78 sheets divided into five classes, on which were imprinted symbolic representations of Egyptian teachings. A forgery that historians say was already widespread in the Masonic circles he frequented.

In the Renaissance, at the time of its birth and spread, the game of tarot was simply a kind of trump, a game of trick-taking in which each player possessed a certain number of cards, and at each turn the strongest card beat the lowest; the winner was the one who had obtained the highest number of points, depending on the most powerful cards. At first the pastime was called triumphi, but later its name was changed to “tarot.” it seems that the term referring to the game was first introduced in a register of accounts of the Este court dating back to 1505; furthermore, it seems that the term was used as a synonym for “mad” or “insane” in some lyrical compositions of the time, or it could be associated with Bacchus, a deity who accompanied the players, who paid homage to him with wine, and who led to madness. Or a further meaning would refer to the meaning of attack, from the expression “I castling you,” for the stronger trick cards with which a player could win against lower cards held by opponents.

The Sola Busca deck consists of seventy-eight cards, including twenty-two “triumphs” or “Major Arcana” and fifty-six cards of the four traditional suits, namely deniers, swords, clubs, and cups. The Major Arcana consist of twenty-one numbered cards plus the Fool, and among them appear such characters as Marius, Catulus, Deo Taurus, Nero, Cato, Bocho, and Nabuchodenasor, who name their respective cards. These are characters belonging to Roman history, but they are not meant to illustrate figures of leaders as positive heroes or exemplars of virtue and valor: rather, they are characters related to the internecine wars that tore Rome apart throughout its history, although their precise meaning still eludes us today. Then there are characters from the Bible and figures that are more difficult to identify: for example, Carbone could be identified with Ludovico Carbone, orator of the court of Ferrara in the second half of the fifteenth century; Bocho could be identified with Bochus, king of Mauritania as well as father-in-law of Jugurthas king of Numidia, and could be symbolic of the Traitor, in that he had betrayed his son-in-law and ally by handing him over to the Romans; and again Cato Uticense could represent Death, in that he committed suicide.

|

| Nicola di mastro Antonio and anonymous illuminator, The Fool, from the Tarot Sola Busca |

|

| Nicola di mastro Antonio and anonymous illuminator, Ten of Cups, from the Tarot Sola Busca |

|

| Nicola di mastro Antonio and anonymous illuminator, Triumph XIV, from the Tarot Sola Busca |

The fifty-six cards of the Sola Busca deck, on the other hand, are considered a rarity, since they generally simply depict the four suits, but here they are accompanied by more complex representations: hence a close connection with the alchemical-hermetic culture has been suggested. The denarii would seem to allude to the production of coins and to theopus alchemicum, as a process of transforming matter from metals; in the sticks alchemy would be exemplified by the link between theopus alchemicum and agriculture, such as the three that depicts a head pierced by three sticks, probably symbols of gold, silver, and mercury, and whose mouth is closed by a garland. The ten of cups, on the other hand, would represent Hermes Trismegistus, author of Hermeticism, considered an occult doctrine of alchemists. And again, the three of swords with a heart, symbol of fire, pierced by three swords, symbols of metals. However, alchemical elements have also been recognized in the Triumphs: in the sixth, Mercury is represented, and in the sixteenth, Olive, which would symbolize the triumph of the Sun and thus allude to gold, a hypothesis supported by the presence of a basilisk (a mythical being halfway between a rooster and a snake, necessary to obtain gold). The king of swords would be identified with Alexander the Great: the ruler, considered the “new sun,” would be an iconographic symbol of gold, so he too would be closely linked to alchemy and immortality. Other cards in the deck are connected to his figure: the horse of swords would be Zeus Ammon, Alexander’s father according to the oracle of Siwa, the queen of swords is his mother Olympias, and the horse of cups would be Natanabo, his teacher.

Another historical figure would be recognized in the upper medallion of the two of denarii: Hercules I d’Este, thus linked to the Este court of Ferrara.

The seventy-eight Sola Busca tarots are prints on paper from burin engravings, mounted anciently on cardboard, later illuminated with tempera and gold. According to recent scholarship, the engravings have been attributed to the Ancona painter Nicola di maestro Antonio (Ancona, late 15th century - after 1511), an artist influenced by painters of the school of Francesco Squarcione (Padua, 1397 - 1468), such as Marco Zoppo (Cento, 1433 - Venice, 1478) and Giorgio Schiavone (Scardona, 1433/1436 - Šibenik, 1504). Instead, it has been speculated that the miniatures were completed in Venice thanks to Marin Sanudo the Younger, a humanist and historian: the coats of arms visible in the deck would refer to the Venetian noble families of Venier and Sanudo, and the initials M.S. suggest those of the humanist.

Because of its great documentary importance and extraordinary quality, the Sola Busca deck was purchased in 2009 by the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities with the right of first refusal and destined for the Brera Art Gallery, where it is still kept and where it was celebrated, between 2012 and 2013, with a significant exhibition that made possible the most recent discoveries.

Essential bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.