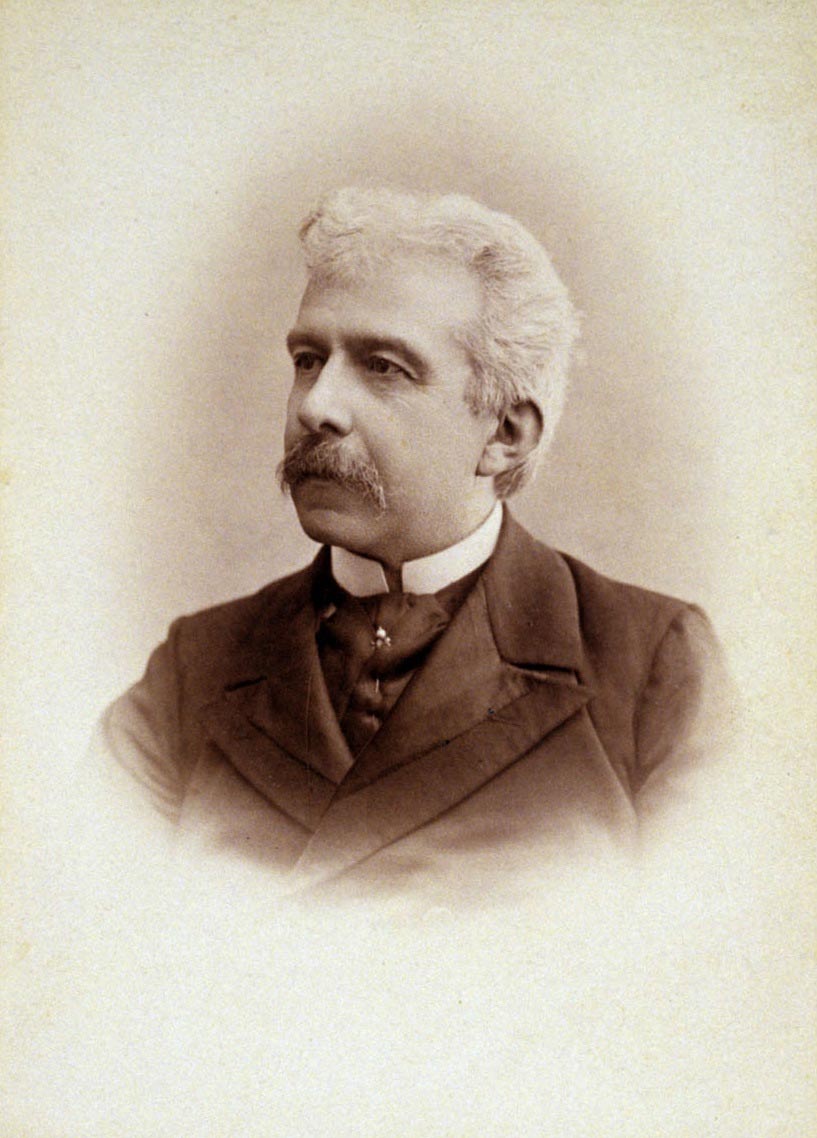

Poet, writer, senator, several times a candidate for the Nobel Prize in Literature, which, however, he never managed to win, a refined interpreter of the conflict between faith and science, and an investigator of the way Catholicism was preparing to face modernity in the late 19th century: Antonio Fogazzaro (Vicenza, 1842 - 1911) was one of the most important Italian writers at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the author of such impactful works as Piccolo mondo antico, the story of a family in the face of the events that led to the Second War of Independence, or as Il Santo, which was also put on the Index for its modernist slant.

There is a strong relationship linking the figure of Antonio Fogazzaro toPraglia Abbey, an ancient monastery in the Euganean Hills whose library, the Biblioteca Statale del Monumento Nazionale di Praglia, now preserves the Fogazzaro Fund, which includes the great writer’s entire library, now carefully guarded by the abbey’s forty monks, a number that makes the Praglia monastic community one of the densest in Italy. The Praglia community had been suppressed in 1867 (when the Veneto was united with Italy), as a result of the post-unification laws that provided, precisely, for the suppression of religious congregations. The Benedictine monks of Praglia would return to their monastery only in 1904: among those who worked to encourage the monks’ return to Praglia was Fogazzaro, who set parts of his novel Piccolo mondo moderno, the second book in the tetralogy of which Piccolo mondo antico, Il Santo and Leila are part, at Praglia. In the meantime, the abbey, which was to be protected as it became a “National Monument” soon after its suppression, had experienced a period of severe degradation.

The sense of desolation and abandonment is well evoked in the pages as the protagonist finds himself, alone, in the abbey once populated by monks: “There was no one there. Piero stood for a while watching the flickering of the dense and minute rain outside the porch, on the thick grass, on the elegant sixteenth-century well, on the lofty flank of the impending monastery to the left with its small arched windows, with the large windows of the eighteenth-century interior staircase, with the trefoil arches of the terracotta frames. He stood watching, eavesdropping. No footsteps, no voices. He recalled to his heart all his good intentions and walked left toward a half-open door. He opened it, had a vision of svelte arches, a sense of pious, admonishing ancient thought, of severe chaste beauty. He entered and nothing more he saw, nothing more he heard of that gentle fifteenth century.” It was a setting well familiar to Fogazzaro, who had visited it for the first time several years earlier, in 1890.

It was precisely in 1890, when Fogazzaro first visited Praglia Abbey, that “he drew from it an impression of desolation and despoliation,” wrote Praglia Library director Guglielmo Scannerini, "which is reflected in the pages of chapter 2 of Piccolo mondo moderno. It is in the mixture of ideological fury and particularistic interests, as well as in the inadequacy, also of means, of the new unified state in protecting the enormous cultural and artistic heritage confiscated from ecclesiastical entities, that the incredible delay in the application of the 1866-1867 legislation establishing ’National Monuments’ to Praglia Abbey, which occurred only from 1899, finds explanation. The spoliation of the works of art and the library had by then been almost completely accomplished. Unfortunate case, and moreover not unique." Fogazzaro took an interest in the case of the abbey and together with other personalities, including the economist Luigi Luzzatti, who was at the time minister of the treasury of the Kingdom of Italy and a few years later would become president of the council, favored the recovery of the monastic complex by the Benedictines, who, in 1904, when they regained possession of the monastery were not slow to thank him: “On behalf of my entire Community,” wrote the new abbot, Bede Cardinal, a few months after the date of their return, April 26, 1904, “I extend to you the warmest thanks and assure you that we will never forget the very great part you played in the reopening of this abbey.”

Even in the following years Fogazzaro did not stop supporting the abbey, and in particular he worked precisely to rebuild the Monastery Library: as president of the Deputation in charge of the Bertoliana Library in Vicenza he arranged to donate the duplicates of the Vicenza institute to the Praglia Library, which had been heavily impoverished after the suppression, and Fogazzaro himself spared no donations. This relationship continued even after the writer’s death: in fact, the heirs decided to donate to Praglia, in 1948, a substantial nucleus consisting of 800 books and 1,300 pamphlets. The latter donation, wrote scholar Paolo Marangon, “significantly enriched the monastery’s book patrimony with rare and sometimes unobtainable texts, but above all it halted the dispersion of the writer’s private library, severely damaged by the bombing of December 28, 1943, and thanks to the patient and meticulous cataloguing work of the librarians made it possible for Fogazzaro scholars to consult it, at least for the book section.”

A gesture that therefore had as a result a double beneficial effect: it replenished the collection of the Praglia Library and ensured that the book heritage on which Fogazzaro had studied and worked was not lost, and this allowed scholars who approached his figure to have a more complete overview of his culture, being able to investigate even topics little addressed even by the critics who until then had dealt with Fogazzaro, such as spiritualism, evolutionism and modernism. The work then went on: in 2011, with the cataloguing of the pamphlets (which opened up further, unprecedented possibilities for the study of Fogazzaro, since the review of the material revealed further dimensions of his public engagement and new information on his relationships, thus resulting as valuable sources for bringing out the fabric of the writer’s relationships), the census of the entire fund was finished, which is now therefore fully accessible to all. A work that has also concluded, Marangon wrote, a “symbolic circle of reciprocal gifts,” since “if Fogazzaro is to be counted among the protagonists of the rebirth of the abbey in the early twentieth century, the monastic community has made a fundamental contribution in recent decades to the full recovery of his library and thus also to a deeper knowledge of his culture and biography.”

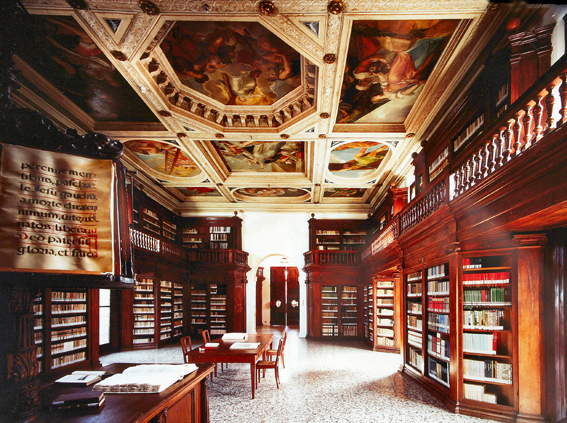

The Praglia Library was founded in the 11th century along with the abbey, although we have very little information about the first three centuries of its history. It seems that the small size of the community in medieval times, despite the substantial holdings of the Library, did not allow the birth of a true Scriptorium. Few codices belonging to the monastery have come down to us: mainly texts related to the daily needs of the Praglia community. The patrimony grew with the inheritance of Abbot Antonio da Casale (1444) and after Praglia entered the Congregation of Santa Giustina (1448). Following the Napoleonic suppressions, the Praglia library was dispersed and was rebuilt only in the 19th century, in great shortage of means and mainly thanks to donations: thus books from other libraries dispersed after the suppressions arrived at Praglia.

In 1867, the post-Unitarian suppressions dispersed the library again, which was able to rebuild again thanks to donations after 1904, when Praglia Abbey was replaced by monks. After the nationalization of the abbey, the library was opened to the public and the holdings began to increase again (today it has over 130,000 volumes). In addition, the library gained new spaces, especially with the adaptation to a reference room (1954) of the former “Common Fire Room,” located on the lower floor of the 16th-century library. Finally, in 2005, the library warehouse located on the first floor was inaugurated, and on the same occasion a passageway room in which traces of the vanished medieval buildings are preserved was recovered.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.