Edward Hopper (Nyack, 1882 - Manhattan, 1967), was one of the leading exponents of American realism . Hopper’s canvases are set in towns and small villages not far from New York City, and the people who populate them, though close, are mentally distant. The atmosphere Hopper depicted in his canvases instills an illusory serenity, as the human beings he depicted in the new urban spaces are as alienated, lost in their own world, almost unreal.

The early years of his artistic career were not among his best. Hopper could not afford to devote himself only to painting, so for a long time he had to work for an advertising agency, this was very frustrating for the artist who did not feel free to express his art. In the mid-1920s, however, things changed: many critics began to appreciate his art and some art centers, museums, and galleries devoted personal exhibitions to him. Influenced by the Impressionists and fascinated by Degas, Edward Hopper studied the theme of light extensively. His highly original and personal style was greatly admired not only by artists and art critics but also by film directors such as Alfred Hitchcock, who in fact was inspired by many of his canvases.

Edward Hopper was born on July 22, 1882, in Nyack, a small town in upstate New York. His parents Garret Henry and Elizabeth Griffiths Smiths, educated middle-class Americans, ran a textile store. Young Hopper spent his early childhood watching and drawing boats on the Hudson River and the Nyack boatyard, showing an early interest in drawing. His parents, when they noticed their son’s talent, gave him magazines and books on art. In 1899 Hopper enrolled in the Correspondence School of Illustrating in New York. A year later Edward transferred to the more famous New York School of Art, determined to follow his own path as an artist. At the new school he began taking painting classes from the American masters of the caliber of Robert Henri, William Marritt Chase, and Kenneth Hayes Miller. All of the diverse teachers were important in his artistic training, but the one to whom Hopper felt closest was Robert Henri. According to Henri, a realist painter, painting cannot be separated from life. When Hopper graduated he began his career as an illustrator at an advertising agency in New York, and with the money he earned he decided to go to Paris. In 1906 he arrived in the French capital and took lodging on Rue de Lille, near the Louvre Museum. Here he did not attend schools, as many Americans did, but experienced art independently by visiting museums, exhibitions and cafes, painting in the open air along the Seine. He was greatly fascinated by the Symbolist poets and the Impressionists; he disliked Paul Cézanne’s canvases but was enraptured by Edgar Degas’s ballerinas. After the trip to Paris Hopper’s palette lightened and his interest turned mainly to light.

He returned to New York in 1908 and, with the encouragement of master Robert Henri, organized an exhibition, in which the artist participated with three paintings made during his Paris sojourn. In 1909 he left again for Paris where he stayed for several months between spring and summer. The trip was very important because it confirmed the painter’s choice to undertake a realistic type of art, made up of post-Impressionist suggestions and a definite interest in architectural forms. He returned to Paris in 1910, for the last time, after which he never crossed the Atlantic again. Due to financial problems, Hopper had to keep his job as an advertising illustrator, which he began in 1906 and did not finish until 1924. It was very frustrating for the artist not to be able to freely express his artistic flair to make images that would work in the marketplace. Many critics, however, believe that even in the illustrations one can find methods and motifs not unlike his canvases. Important was the summer of 1912 that he spent in the company of painter Leon Kroll in Gloucester, a picturesque nearby New England village where many American artists gathered. Here Hopper began to select American subjects, abandoning some European-style motifs.

1913 was the year of theArmory Show, the first exhibition that brought European avant-garde painting to the American public. Hopper also participated in the show with a painting that was later sold. In 1920, New York’s leading contemporary art center, the Whitney Studio Club, organized Edward Hopper’s first solo exhibition. Sixteen paintings were exhibited at the show: however, the artist could neither sell paintings nor receive any critical reviews. The first monographic article devoted to Hopper was dated 1922, and it was in the same year that he saw Josephine Verstille Nivison again, a student of Robert Henri whom he had gotten to know a few years earlier and who became the model for all his works. With Josephine he spent the summer in Gloucester and, stimulated by her, resumed painting in watercolor, after a brief period in which he devoted himself to etching. He participated in an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, and after the institution bought one of his canvases, exhibitions and reviews of his work intensified for the artist. 1924 was a very important year for Hopper because he married his partner Josephine and exhibited a number of watercolors at the Rehn Gallery: the exhibition marked the artist’s definitive establishment commercially as well. With his wife they began spending the summer months on Cape Cod, where he drew inspiration for many of his famous works. This was the period when Hopper fine-tuned the pictorial style that would characterize his works: the early views of New England houses, the interiors of rooms, the strong chiaroscuro contrasts. Subsequent exhibitions and numerous positive reviews by critics enabled him to become known throughout the country and Europe. In addition, the artist came to be recognized as one of the most emblematic interpreters of American realism. Edward Hopper died in his studio home in New York in 1967.

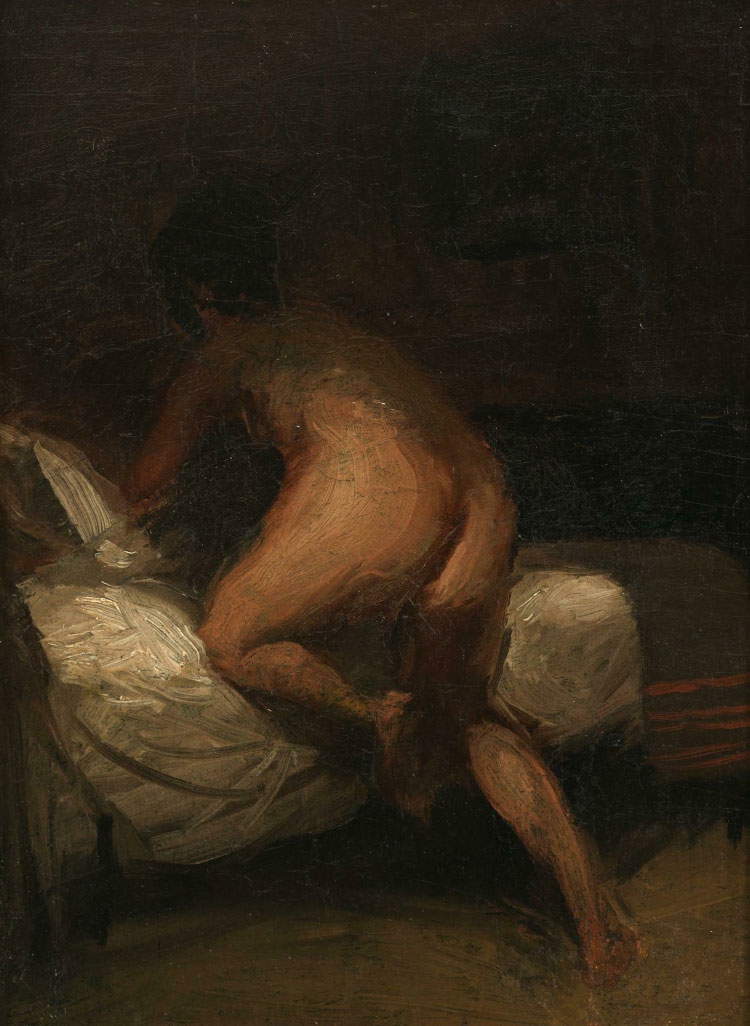

From Edward Hopper’s earliest early works it is possible to identify certain themes that he later developed more thoroughly in the 1930s and 1940s such as pictorial realism, the simplification of architectural subjects and planes, and the rather flat colors of his palette. The scenes imprinted on his canvas reflect loneliness and a sense of isolation: constant themes in his work. Among Edward Hopper’s earliest works, guided by master Robert Henri, appears Nude Climbing on a Bed (1903-1905).

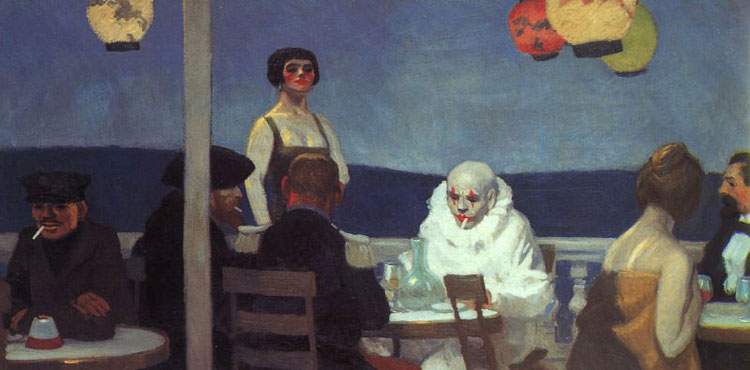

Already in this canvas the theme of the solitary figure is veiled, although the painter’s interest was directed more toward pictorial rendering. At this date Hopper was not yet in Paris, in fact the color palette is much darker, compared to the luminous work Le bistro (1909). In the latter, in the left foreground, a man and woman sitting at a small table inevitably hark back to Edgar Degas’s workAbsinthe . The rest of the canvas was constructed through clear overlays and architectural clusters. After the 1909 trip to Paris, Hopper’s interest turned to the theme of light, the flare of painted subjects, in which he showed a certain debt to Impressionism. In the summer of 1914 Hopper produced Soir Bleau: the canvas might suggest that it was made during the French period, but the opposite is true. A Pierrot is depicted in the center of the work, next to a heavily made-up woman, a very elegantly dressed couple, and a man sitting at a table alone: each of them seems to be performing a play .

The whole place is pervaded by a rather eerie calm. What all the characters have in common is boredom and loneliness. Between 1916 and 1919 Hopper spent the summer in Maine: during this period the artist painted mostly landscapes, bridges, and houses. The work Small Town Station depicts a train station in a small Maine town. The canvas anticipates some elements of the more famous House by the Railroad (1925) in which a mighty isolated house rises next to a railroad. The railroad that makes the house, now almost a relic of the past, almost inaccessible, may symbolize civilization and industrialization encroaching on nature. It is, moreover, interesting to note that Hopper’s paintings greatly influenced cinema. A case in point is the film Psycho by famed director Alfred Hitchcock, where the house in which the murders take place is not unlike Hopper’s.

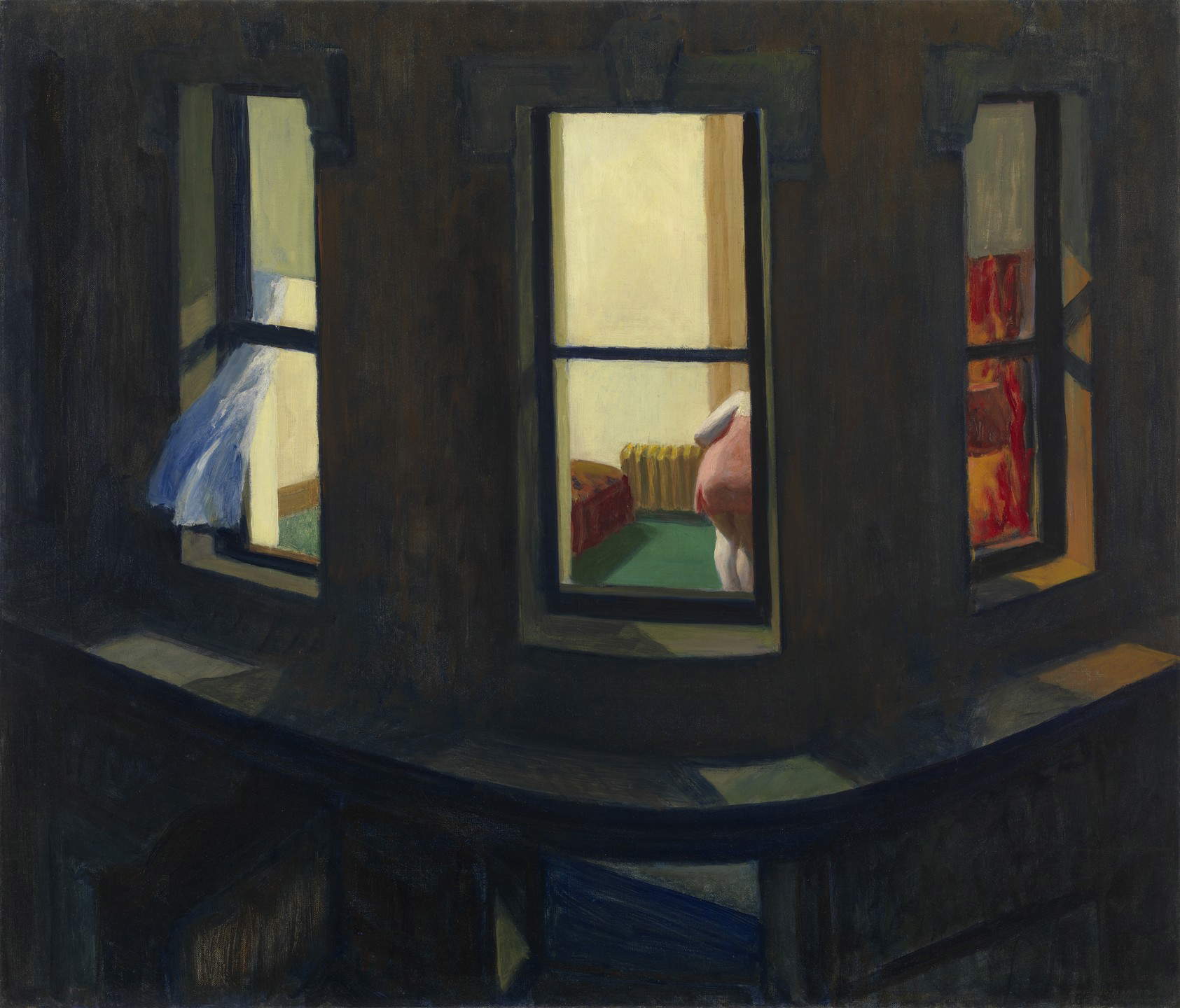

In 1926 he painted Eleven in the Morning in which natural light from outside illuminates the naked woman sitting in an armchair in front of the windows. The work emphasizes two elements that characterized Hopper’s artistic production: on the one hand, the female nude, which often recurs in his canvases, and on the other hand, the desolation that pervades these figures. Interestingly, the open window indicates a dialogue between inside and outside that the artist sought in all his canvases. Even in Windows at Night (1928) the fluttering curtain relates interior and exterior space. Here Hopper’s composition moves across three windows of which the center one follows the curvilinear progression of the building. From the center window of glimpses the figure of a woman caught from behind. It is possible image that the painter, for the making of the work, was in another interior space, an equally intimate space. This was the same principle also followed by director Alfred Hitchcock for the 1954 film Rear Window , in which a man, forced to stay at home, becomes a witness to a murder taking place in the house across the street but a spectator to the daily events of those who live there.

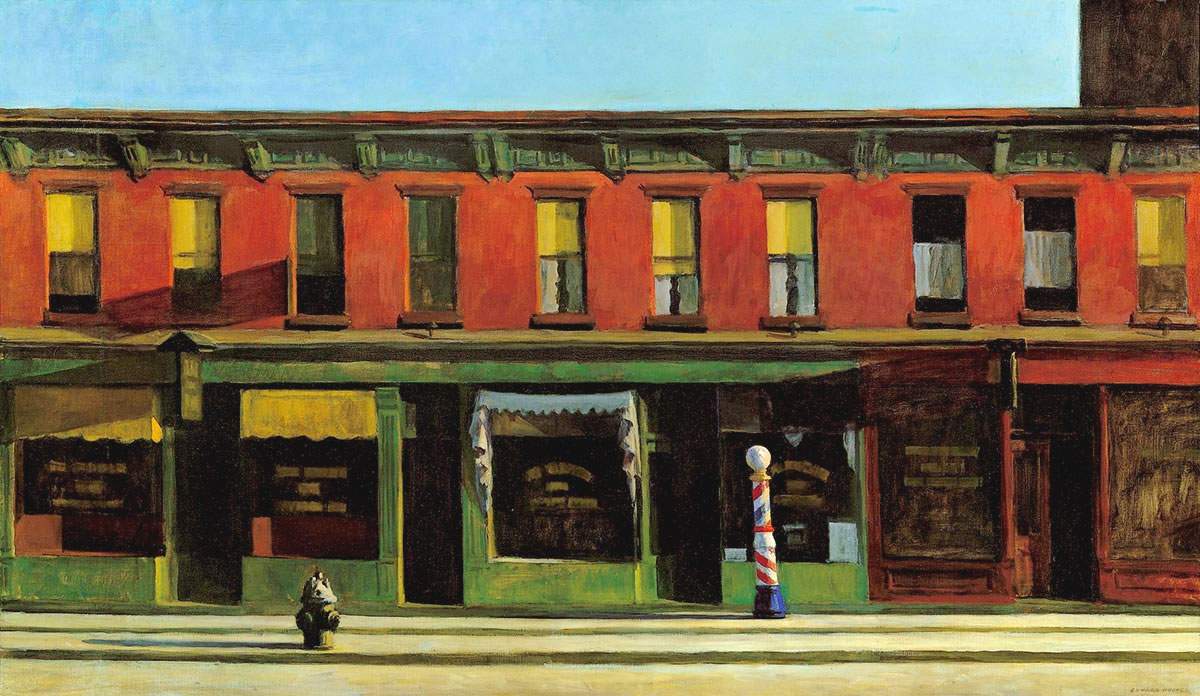

Early Sunday Morning (1930) is one of the American painter’s most famous works. Hopper’s oil here has a horizontal progression, also accentuated by the canvas format. The stores differ in different draperies and details, as do the windows. The street, painted early in the morning, exudes a sense of tranquility also accentuated by the sunlight illuminating the buildings and the street. It is important to note that the human figure is missing here; Hopper initially wanted to include a figure on one of the windows placed above, but in the end he decided to emphasize architecture, a great passion of the painter. Neutrality was another artistic virtue of the painter. In Hotel Room (1931) a woman is sitting on her bed intent on reading. The figure could be interpreted as a lonely traveler, an abandoned lover or a woman waiting for someone.

One of Hopper’s main themes were the solitary figures, the protagonists of his canvases. Many of these figures are women gazing into an open space or intent on reading as in Compartment C, Carriage 293, (1938): a woman is seated in the train compartment absolved from reading the magazine and unconcerned about those watching her. The examples could continue further, but the interesting thing to note is how all these solitary figures appear unable to communicate, even when several characters are in one painting.

In 1940 Hopper painted the famous canvas entitled Gasoline. Hopper stated to art critic Lloyd Goodrich that for a long time he searched for a gas station as well as the one he had in mind but not finding it, he made one inspired by the many gas stations he had seen. The theme is that of the other works: a lone figure, nature, and signs of civilization. The red access gas pumps and station sign seem threatened by the nature in front, which seems to claim the space that has been taken from it.

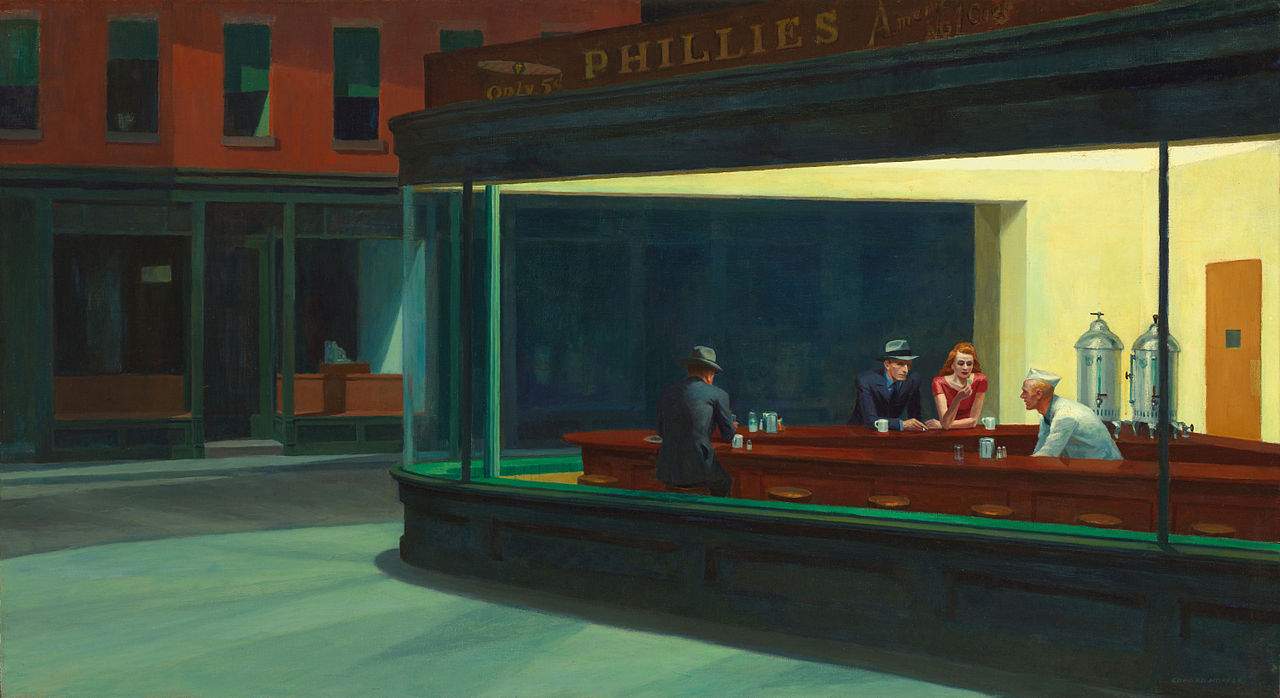

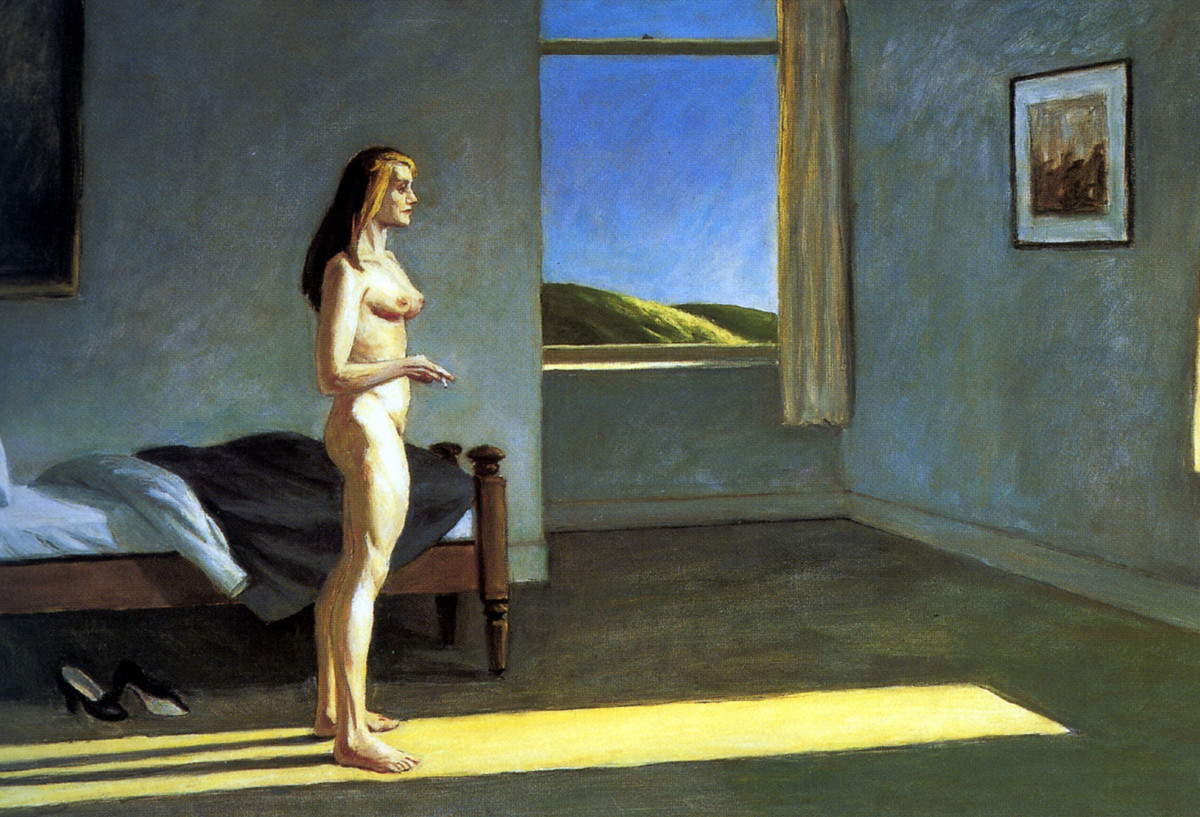

One of Hopper’s most iconic canvases is Nottambuli (1942). The scene is set in a late-night restaurant on the Greenwich Village intersection in Manhattan. The meaning of the work remains rather ambiguous, and therefore interpretable in various ways. Hopper depicted the allure of the night, brightened by the artificial light prevening from the restaurant. The large glass window allows a view of the people inside: the barman serves the last three customers, a seemingly mute couple, and a lone man seen from behind. The artist’s typical theme returns in this work as well: there is no interaction whatsoever, the atmosphere is not the most serene, and throughout the entire environment, both inside the bar and outside reigns, a tomb-like silence. In the paintings between the 1940s and 1950s, the core of his research resurfaced, the one he discovered in Paris and perfected in America: the theme of light. Also emblematic are the titles of his works such as: Morning Sun (1952) and A Woman in the Sun (1961) just to mention the most famous ones. In the first canvas it is possible to perceive very well the artist’s accurate study toward every effect of light, the meticulous analysis of this particular phenomenon. The careful study moreover is evidenced by some sketches of drawings preserved today in the Whitney Museum. In contrast, in the second canvas, A Woman in the Sun (1961), the female figure stands nude, holding a cigarette and her body lies within a perimeter of rectangle of light. It is also interesting to note the contradictory impression of the woman: on the one hand, the attitude and pose she assumes indicates security and tranquility; on the other hand, however, her nudity exposed totally to sunlight makes her very vulnerable. All of Edward Hopper’s canvases are dominated by silence, solitude, serene and disturbing interiors at the same time. Hopper was one of the artists who best synthesized theAmerican way of life, but not the one made of skyscrapers and canned food, but the one affected by the economic crisis of the 1930s.

Edward Hopper’s works are mainly found in the United States. Point of departure is New York, particularly in the Greenwich Village neighborhood where it is possible to visit the house-studio where the artist lived for most of his life. Remaining still in the Big Apple, the Whitney Museum of American Art, which was among the first museums to acquire the works of the famous artist, is not to be missed. Moving a little further north of the Whitney Museum we find the MoMa, which houses must-see masterpieces by Hopper and therefore impossible not to stop by.

Finally, as a final and unmissable stop is Boston, at the Museum of Fine Art, where you can see some of the painter’s most beautiful masterpieces. Other museums that preserve some canvases are: Manchester City Art Gallery, Tate Modern in London, Art Gallery of Ontario (Toronto), Neue Nationalgalerie (Berlin), National Gallery of Canada (Ottawa), and finally The Edward Hopper Foundation (London), an archive dedicated to the great American artist.

|

| Edward Hopper: the life, works, and loneliness of the American way of life |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.