There is an emptiness that nails, made of all that we have chosen not to be, all those versions of us that we have left behind out of fear, out of inertia, out of survival. An emptiness that does not show itself violently, but creeps in like a subtle, unmentionable pain that knows the exact places to strike, to dig, to morbidly rummage. It is made of nights filled with unspoken words, of rooms shared with those who could not understand us, of loves interrupted before they even have a name. It is an absence that keeps us awake even when we do not name it, that returns in the most mundane details: a light on, a voice-over, a memory never quite our own.

Then there is another emptiness, rarer and more fragile, which does not punish but welcomes, does not hurt but consoles. It is the one that allows us to stop pretending, that allows us to remain, for a feeble instant, defenseless. It is the lack that does not ask but offers: that which invites us to stop, to breathe, to be nothing and, in that nothingness, finally, to be. There is the emptiness of cosmic space: an absolute silence among the stars. That of subatomic particles, the nothingness that holds everything together. But it is the existential void that is the most difficult to sustain, and we try to fill it as we can: with words, gestures, images, background noise, addictions. We speed up, we get distracted, we hustle, yet the nothingness remains, accompanies us, hides between the cracks and, sooner or later, catches up with us because it will always have a longer breath than ours.

Psychiatrist Viktor Frankl told how man cannot live without meaning, and that the emptiness that arises from its absence can become a silent and devastating trap. He called it “existential emptiness” since it is a slowly consuming condition that occurs when we stop feeling a why, a connection between what we are and what we do. He experienced it directly and brutally in Nazi concentration camps, an experience that is at the heart of his best-known work, Man’s Search for Meaning. During his imprisonment in Auschwitz, Dachau and other camps, Frankl lost his pregnant wife, parents and brother and experienced total dispossession: of name, body, freedom, future. In that absolute emptiness, where humanity seemed annihilated, Frankl observed something fundamental; namely, that even in the most extreme suffering, man retains an inner freedom, that of choosing his attitude in the face of pain. “Everything can be taken away from a man except one thing: the last of human freedoms-to be able to choose one’s attitude in any given situation, even if only for a few seconds.”

For Frankl, existential emptiness is not just a modern psychological condition, but a territory where the possibility of meaning is at stake, and it is precisely when everything collapses that man has the opportunity to ask the fundamental question: why live? For what to endure? And the answer, for Frankl, does not come from outside, but is an active construction, an orientation that everyone is called upon to generate. His is never an escape from suffering, but the ability to attribute meaning to suffering itself, and that seemingly unbearable emptiness could become inhabited space, if only we stop fearing it and start looking at it as a possibility. It is not fullness that saves us, but the ability to turn absence into direction and loss into orientation. The mistake we often make is perhaps that we never give it space. We fear emptiness as if it were a flaw in the fabric of our lives, as an error to be corrected, and even in art, in music, in writing every surface must be full, every note continuous, every phrase an unbroken concatenation. For silence is intruder, interruption discomfort, the blank canvas adversary. But if we stopped fighting it, this seemingly lacerating and tedious emptiness, and simply learned to inhabit it, to care for it, we would understand that it is nothing more than the breath that precedes the word, the waiting before a gesture, the canvas still intact. It is the necessary pause between beats. It is fertile ground for imagination, for creation, for understanding all that eludes us. Emptiness is not only what is missing: it is also what can still be born. But emptiness is not filled. It is listened to. It is inhabited. In a time that urges us not to stop, inhabiting nothingness seems a radical act; it means staying, listening, resisting the fiercely human temptation to saturate and, simply accepting that, in the uncertain threshold between fullness and nothingness, something cannot really happen.

This was timely understood by Robert Ryman, who chose white not to undo but to affirm. A painting, his, that does not represent, but exposes; that does not shout, but withholds. In his works, light settles, margins dissolve, and the wall ceases to be a background, but becomes part of the work. Toward the end of the 1960s, Ryman’s work takes a sensual turn: his surfaces become light, translucent, almost uncertain. In works such as Twin of 1966 and Adelphi of 1967, the white paint spreads thinly, close to the extreme edge of the support, as if trying to contain the void without encasing it. In Adelphi, the canvas is not even stretched, but rests loosely on waxed paper and is stapled directly to the wall. It is in this gesture that Ryman begins to romanticize the wall, to make the frame part of the painting, to blur the edges between what is art and what is space. But it is with the Surface Veil series of 1970 that this reflection is amplified and he creates impalpable surfaces, painted on fiberglass or oiled paper, attached to the wall with short strips of tape. There is no longer any distance between support and environment: the wall enters the work and becomes its skin, and, looking at these compositions, it is difficult to tell where the painting ends and the wall begins, where matter dissolves and where, instead, it becomes presence. White, here, is not full light but fog, suspension, latency. It is as if Ryman is asking us to stay there, at the exact point where meaning is not yet decided.

“My paintings are so involved with the wall that sometimes it’s almost as if they were painted on the wall,” he asserted, and I think it is in that threshold, in that gap between presence and absence, that his work finds the real power that, rather than affirming, suggests, waits. As in Robert Ryman’s work, in Paolo Sorrentino’s It was the Hand of God, absence is neither decoration nor lack, but tension between what is there and what could be. Ryman works on whiteness as a space to be inhabited, to be traversed without distraction; Sorrentino, on the other hand, allows silence to take shape , to become narrative substance. There are moments in the film when the music retracts altogether, when sound disappears and only a sonic abyss remains that weighs more than any dialogue. It is the same emptiness that follows loss, that lacerating sensation that remains after the trauma, that opens wide. There, in the silence that invades the protagonist’s home, the absence of the parents is not spoken, but felt. Mourning is not told didactically, but remains suspended, cruel, real. Like Ryman’s white, like his light, almost dematerialized canvases, Sorrentino makes absence a visual and emotional field to be traversed, but perhaps the artist who most of all made emptiness a real language was composer John Cage.

In 1951, John Cage entered an anechoic chamber convinced that he would encounter absolute silence, but he came out with a brutal and lapidary truth, namely that silence does not exist.

Inside that room, designed to absorb all sound, he heard two distinct noises: the beating of his heart, deep and regular, and the workings of his nervous system, which emitted a louder, more continuous sound. At that moment he understood that even when everything is silent, the body speaks and that reality does not know perfect emptiness. Every space is already inhabited. Every expectation is already noise.

From that experience was born 4’33", his most famous and most discussed piece: four minutes and thirty-three seconds of “played” silence, in which the performer never touches the instrument, but the emptiness is never sterile. His is a listening time that requires only to pay attention, to stop controlling the sound and take in what is already there. 4’33" has a score, a marked tempo, a frame. The structure is there, but what fills it is unpredictable, and in that apparent absence, anything can happen: the cough of a spectator, the noise of the hall or even simply the awareness of one’s own breathing.

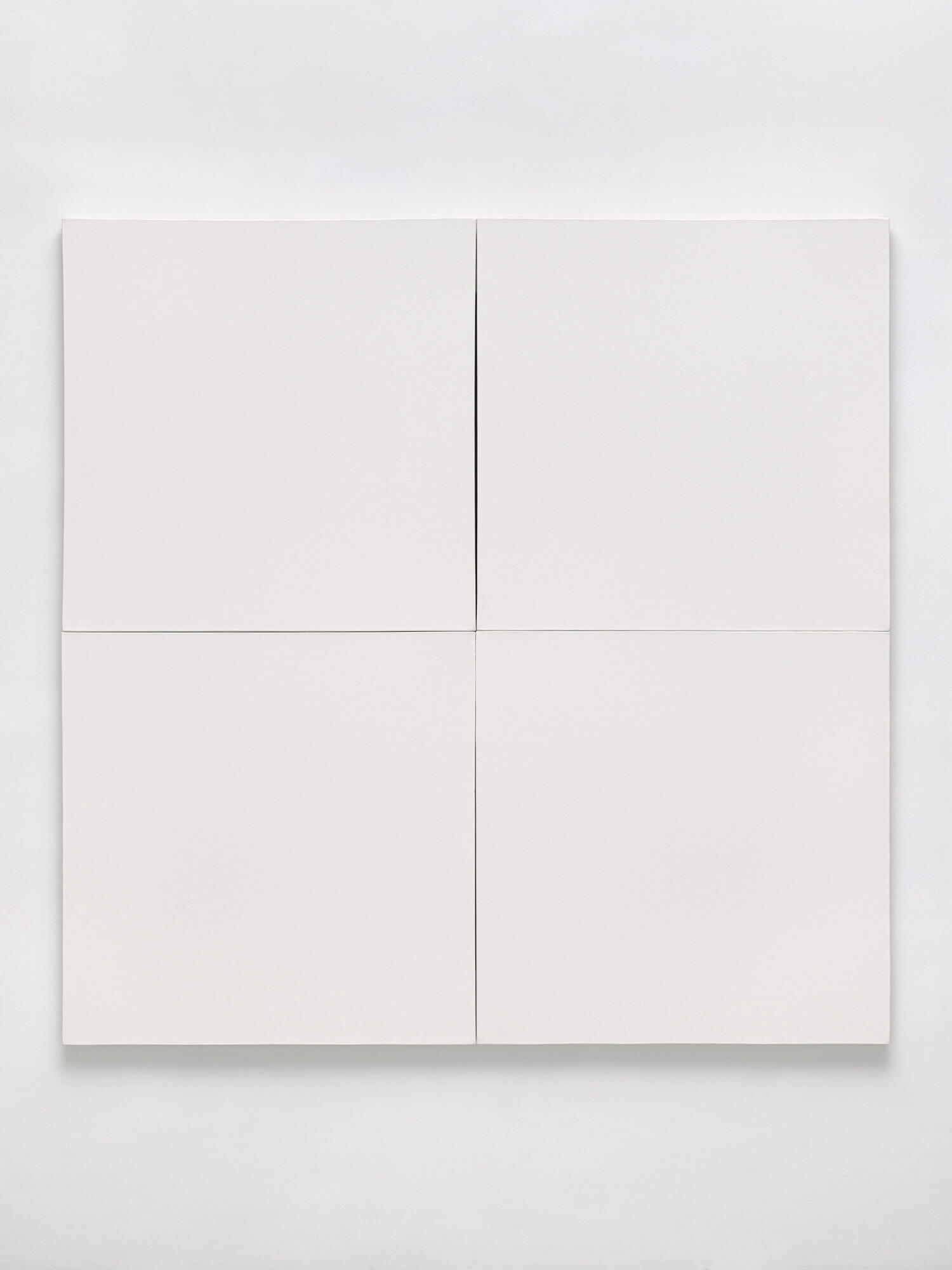

In his book Silence: Lectures and Writings, Cage wrote, “Wherever we are, what we hear is mostly noise. When we ignore it, it disturbs us. When we listen to it, we find it fascinating.” And perhaps this is what restores even more awareness to the work: in existing, in being there even when we find nothing around. And yet, this work that still disorients, enthralls, moves, was not born out of nothing nor out of a provocation for its own sake. Cage himself recounted that it was the example of Robert Rauschenberg that gave him the courage (or perhaps the necessity) to write the piece: when he first saw his 1951 White Paintings, those monochrome canvases arranged in completely white grids, he understood that music, too, had to catch up, to accept art’s radical invitation to stop filling.

The White Paintings offered no images, no content, but at the same time they were empty surfaces only in appearance, ready to welcome reflections, shadows, presences. They represented nothing, but they welcomed everything. They were spaces of attention that were activated the moment someone walked past them, in the way the light changed, in the imperceptible movement of the air, and Cage recognized in those canvases a threshold he could no longer ignore. “To whom it may concern: the white paintings came first; my silent piece came later,” Cage stated again inSilence. Lectures and writings. That painterly gesture was thus the origin of a new way of listening, and 4’33" became a kind of sound transposition of those white paintings, a space to be inhabited without pretension, a time not to be dominated.

Elsewhere, too, in another time, another language was able to name the same tremor. In the Book of Job, man discovers himself naked before an absence that cannot be explained or filled: “But, behold, if I go to the east, he is not there; if to the west, I do not find him; if to the north, when he works there, I do not see him; he hides himself in the south, I do not glimpse him.” Job seeks God in every direction, but he does not find him, and what annihilates him is not the darkness, but the hiding presence, the lacerating silence. It is an emptiness inhabited by something that escapes and, in fact, it is not the absence that wounds him, but the impossibility of seeing that which also exists: “Therefore before him I am terrified; when I think of him, I am afraid of him.” It is not the darkness that frightens, but the vastness that opens when no answer comes, the formless fullness that exposes us, disarms us, reminds us that something is beyond us.

Where Job cries out and receives no answer, Cioran definitively opens wide the abyss that is no longer space to inhabit nor expectation to comprehend, but corrosion, fleshing out, a non-place in which every word risks collapse. Yet, by sweetest irony, it is precisely with words that this man somewhere between a philosopher and a private thinker chooses to struggle. In Précis de décomposition, the aphorism becomes a thin blade, form reduced to the bone, aesthetics bent to intuition. In Cioran, emptiness is the ultimate fate of every idea, the blind spot of thought where no consolation or possibility of redemption can ever be found, but therein lies its appeal: in the ability to resist the seduction of meaning. “To exist means to put to use our part of unreality, it means to vibrate in contact with the emptiness within us.”

The crisis of meaning in Cioran is neither metaphor nor aesthetics, but it is the only reality that survives when everything else decays, and here, then, emptiness becomes an extreme exercise of lucidity, but a lucidity that implodes, that renounces itself. There is no asceticism, no waiting. Only residue. It is an absence, his, that announces nothing, but reveals the very impossibility of being. There is, lurking, a subtle and pernicious temptation: that of converting emptiness into the very surrogate of being, of disguising it as meaning, of attributing to it a function that does not belong to it. But in so doing, one betrays it, distorts it. For emptiness is not born to console nor to offer footholds, for its essential vocation is detachment, radical suspension, non-being. And so a question arises, perhaps the most insidious one: how to adhere to emptiness without being convulsively seduced by it? How to remain in its orbit without projecting oneself into desire, without loading it with a meaning that emptiness itself, by its very nature, does not seek?

In Cioran’s thought, emptiness is also stripped of its negative qualities: it is not nothingness as a threat, but as a lucid and inexorable residue, as a reality that has ceased to demand, a vertigo-free abyss, a dry, sharp, surgical, almost indifferent certainty that does not uproot us but empties us, leaving us with only the essential, that is, the awareness of our non-reality. Heidegger warns us: when we ask “what is nothingness?” we are already treating it as if it were an entity and, in some way, we are already betraying its nature. Nothingness is not something, but that irreducible space that we cannot possess or transform into an object. In paragraph 40 of Being and Time, Heidegger analyzes the fundamental emotional situation of anguish, distinguishing it from fear. The latter has an object, anguish does not, it is not locatable, it is not “of” something, it is the perception that the world, as we know it, may give way under our feet and it is at that moment that the “nothingness” and the “in-ness”, the sudden suspension of all certainty, is revealed. The world does not disappear, but it loses meaning and everything that was familiar suddenly becomes foreign. Guilt, in this horizon, is not a moral error, but an ontological form: beingness is guilty because it is the foundation of a nullity, because it is thrown into an existence it has not chosen, but which it must inhabit nonetheless, and death is not the end as an event, but the possibility of the pure, simple, exquisite impossibility of beingness. And in this possibility, radical and irreducible, the human being is called to decide to be himself, to assume his own nothingness as a starting point, not as a condemnation. For Heidegger, nothingness is not nihilism, not ontological lack or worthlessness, not defect, but the changing structure of existence. A “not” that does not take away, but makes visible existence in its fragility and truth.

In Japan, that emptiness has the name “Ma” (間) and is not what is missing, but what connects. It is the invisible margin between gestures, the silent echo between words, the thin space where one breath ends and the other begins. In Ma, this is not defect but rhythm, it is not suspension but form, and it is that subtle tension that allows meaning to emerge and encounter to happen and breathe. Yoshida Kenkō, in his Idle Hours, also reflected on the silent fascination of imperfect and transitory things. “It is the emptiness that always contains things,” he noted, as if to remind us that what moves us is never perfection, but the very fragile instant before disappearance as can be a leaf rippled by time, a chipped bowl, a fragment that remains. And it is the same suspension found in Hasegawa Tōhaku’s Shōrin-zu byōbu, a six-panel work that shows not a landscape but what remains of it. The pine trees emerge from the fog without imposing themselves; they are hesitant presences, immersed in a silence that instead of being silent, listens.

This byōbu (a screen painted on paper, edged with silk and mounted on a lacquered frame) was created not to be hung, but to inhabit space, to modify it, to design its rhythm, and its original function was not artistic, but architectural. In Japan, art is never separated from life, in fact the byōbu furnished, divided, opened, gently and was designed to modulate light and accompany the gaze.

In the Shōrin-zu byōbu there is no narrative, no center, only a continuous suspension, an invitation to stillness. Tōhaku paints, then, simply the interval by offering a space in which to pause. It is not in the full that we recognize ourselves, but in that which escapes, which trembles, which resists without declaring itself because things speak loudest when they are about to fade and, perhaps, that is where they resemble us most. It does not answer, it does not console, it does not offer us redemption, but it looks at us and in its gaze, which is silence, it restores us to ourselves. It does not have the form of absence but that of beginning, it does not let itself be possessed but can be listened to, and it does not pass through: it stays, it suspends, it inhabits as it can.

Because inhabiting the void means accepting that you do not have the answers, that you do not understand everything, that you do not always have to heal. It is both a simple and fierce gesture: to remain present even when everything seems to be missing. And in that unspoken, in that fragility that does not close, perhaps the truest thing happens, that of recognizing that to exist is not to possess, but to stay. It is not to fill, but to cherish. It is not knowing, but feeling. Because if emptiness is the condition of existence, then it cannot just be lack, it is matrix. It is not what remains when everything dissolves, but that from which everything can begin.

The author of this article: Francesca Anita Gigli

Francesca Anita Gigli, nata nel 1995, è giornalista e content creator. Collabora con Finestre sull’Arte dal 2022, realizzando articoli per l’edizione online e cartacea. È autrice e voce di Oltre la tela, podcast realizzato con Cubo Unipol, e di Intelligenza Reale, prodotto da Gli Ascoltabili. Dal 2021 porta avanti Likeitalians, progetto attraverso cui racconta l’arte sui social, collaborando con istituzioni e realtà culturali come Palazzo Martinengo, Silvana Editoriale e Ares Torino. Oltre all’attività online, organizza eventi culturali e laboratori didattici nelle scuole. Ha partecipato come speaker a talk divulgativi per enti pubblici, tra cui il Fermento Festival di Urgnano e più volte all’Università di Foggia. È docente di Social Media Marketing e linguaggi dell’arte contemporanea per la grafica.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.