Giorgio Morandi (Bologna, 1890 - 1964) was one of the greatest Italian artists of the early 20th century. The influence he derived from the teachings of Cézanne, André Derain, Cubism and the great masters of the Italian Renaissance enabled him to arrive at an original pictorial synthesis that characterized his works. The young artist at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna at first approached futurism, which, however, abounded early on. The artist’s canvases depict mainly landscapes, especially that of Grizzana, a small Emilian village of which he was very fond, but also flowers and still lifes.

Morandi’s choice to devote himself almost exclusively to these subjects derived from the fact that the painter oriented his art toward an analytical and meditative study of the elements depicted through minimal chromatic and spatial variations. The artist in the early 1920s also had a brief approach to the artistic language of Giorgio De Chirico and Carlo Carrà, a period in which canvases with a metaphysical flavor were born. Despite his isolation and somewhat introverted character, Morandi cultivated friendly relationships with critics, artists, and museum directors, which enabled him to be one of the most externally appreciated artists.

|

| Giorgio Morandi |

Giorgio Morandi was born in Bologna on July 20, 1890, to Andrea and Maria Maccaferri. Giorgio demonstrated a precocious artistic predisposition as evidenced by an elaborate work made public by the Municipal Gallery of Modern Art in Bologna depicting a small composition of Flowers, made around the age of fifteen and already showing the compositional approach that was the artist’s stylistic hallmark. In 1907 Morandi enrolled at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna, where he got to know and befriend Osvaldo Licini and Severo Pozzati . If the first years of his academic training were excellent, the last years spent in the academy were characterized by disputes with the professors: this attitude was due to the change of interests of the artist who already identified his own autonomous and individual language. Influences came from Paris, a city to which his friend Licini moved in 1915, and allowed Morandi to keep abreast of the art of the moment. André Derain, Paul Cézanne, Henri Rousseau and Pablo Picasso were for Morandi the contemporary artists who most influenced him: however, during these years the artist also developed a strong interest in Italian art of the past (in 1910 in Florence he saw the works of Giotto, Massaccio and Paolo Uccello).

With his friends Osvaldo Licini, Severo Pozzati and Giacomo Vespignani, the young Bolognese painter approached Futurist poetics after the artist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti inflamed the spirits of students at the Bolognese Academy. He participated in various Futurist evenings between Modena and Bologna, also visited the Pittura Libera Futurista (1913-14) exhibition that was organized in Florence by the magazine “Lacerba.” The “three tortellini,” as the three friends (Morandi, Licini and Vespignani) were nicknamed because of the hats they wore, held an exhibition at theHotel Baglioni in Bologna, a non-institutional space unrelated to the Academy. Morandi presented thirteen canvases, including Ritratto della sorella (1912-1913), four Paesaggi and two Nature Morte . Although Morandi was closely linked to Futurist poetics, he nevertheless maintained a certain independence from Marinetti’s poetics, turning his gaze beyond the Alps: in particular toward Cubist experiments and the works of Cézanne. Morandi obtained a position as an elementary school drawing teacher from the City of Bologna, which he kept until 1929. In 1915 he was called to arms but after a month, having fallen ill, he was discharged. During these war years Morandi had occasion for reflection and many of his canvases were destroyed by the artist himself. Despite this period of disorientation, the artist found, albeit briefly, solace in metaphysical painting , which is well evidenced by about ten works, among them Natura morta metafisica and Natura morta con palla, both dated 1918. The years 1918-1919 were important for Morandi as he met artists such as Giorgio de Chirico, the main exponent of metaphysical painting, and Carlo Carrà. The two artists gravitated around the magazine of Mario Broglio, a painter and collector, the celebrated “Valori plastici”: the magazine theorized the recovery of national values and a return to figurative painting of the classical model. Giorgio Morandi became one of the main protagonists of this trend. While artists devoted themselves to the plastic experimentation of their canvases, Mario Broglio organized some group exhibitions in Germany (including Berlin) and then in Florence set up the Florentine spring exhibition in 1922. Despite his adherence to “plastic values,” Morandi also participated in other exhibitions: he was present at the two Novecento Italiano exhibitions at the Permanente in Milan in 1926 and 1929, and also, thanks to art critic Margherita Sarfatti, some of his works were exhibited in Paris (Bonaparte Gallery), Basel and Buenos Aires. Morandi was also very close to the intellectual milieu of the magazine "Il Selvaggio" directed by Mino Maccari starting in 1924. Linked to Maccari’s magazine was the “Strapaese” movement whose goal was the restoration of a rural country, founded on tradition and simplicity. Morandi expressed this spirit very well; in fact, Maccari dedicated a long article to the Bolognese painter in the magazine “Il Resto del Carlino” in which he emphasized the “Italianness” and “genuineness” of his art.

The artist’s originality was also celebrated in some foreign exhibitions: in 1929 he was invited to the Carnegie Prize in Pittsburgh, in 1934 some of his works were exhibited at the Italian Art Exhibition organized by the Venice Biennale in the United States, and in 1937 he participated in the Universal Exhibition in Paris. Thanks to the esteem he received from the intellectual and official circles of the period, in 1930 he obtained the chair of printmaking at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna, where he taught until 1956. His participations in the Quadriennali in Rome were also very important: in the third edition, that of 1939, Giorgio Morandi had an entire personal room in which he exhibited forty-two paintings, twelve etchings and two drawings. Although the painter’s works were highly appreciated by important critics, such as Roberto Longhi and Cesare Brandi, and by younger artists, Morandi was awarded the second prize for painting, after the younger Bruno Saetti. Nevertheless, there were various controversies concerning the awarding of the first prize but also about the real value of Morandi’s room, despite the fact that the Bolognese painter was supported by the critics of the time. During World War II Morandi retreated to Grizzana, a small town in the Emilian Apennines, and here he worked on the season that critic Francesco Arcangeli identified as Landscapes and Still Lives from 1942-1943. In the first postwar edition of the Venice Biennale in 1948, the Italian pavilion hosted an anthology of Italian painting (1919-1920), also containing works by Morandi that won him first prize. Winning first prize at the 1948 Venice Biennale allowed the Bolognese master to distinguish himself internationally as well. In the years following the Biennale, Morandi had a rather solitary life immersed in his painting. Following an illness that lasted about a year, the painter died on June 8, 1964, in Bologna.

|

| Giorgio Morandi, Landscape (1911; oil on canvasboard, 37.5 x 52 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Giorgio Morandi, Portrait of Sister (1912; oil on canvas, 37 x 44.3 cm; Bologna, MAMbo) |

|

| Giorgio Morandi, Still Life (1920; oil on canvas, 60.5 x 66.5 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

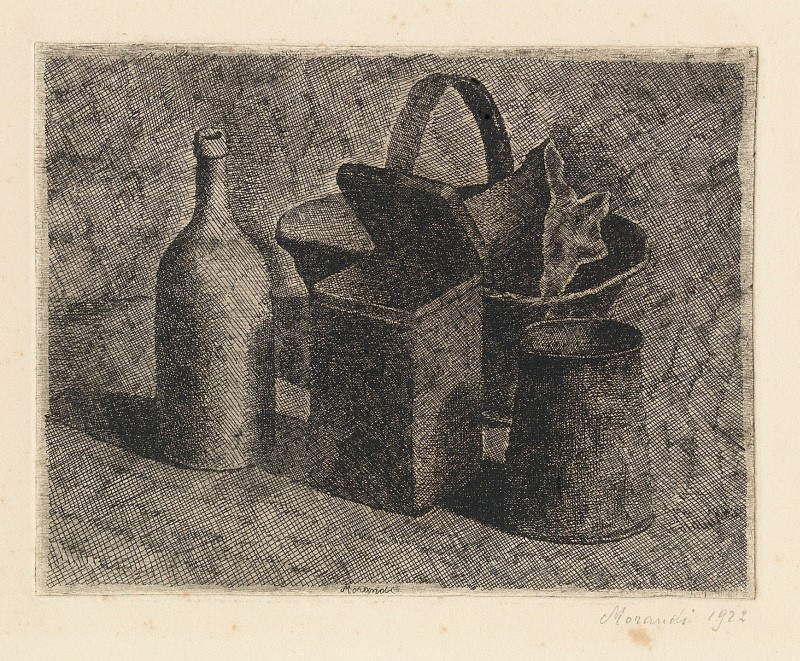

| Giorgio Morandi, Still Life with Basket of Bread (1921; etching on copper, 325 x 463 mm) |

Giorgio Morandi was greatly influenced by the works of Paul Cézanne, as early youthful works such as Landscape (1911) declare. The work shows an already fairly autonomous language, although the strong geometrization of the architecture and the dizzying diagonal across the canvas evoke Cézannean landscapes. Among French artists, Morandi also reserved a particular interest for André Derain, whom he probably got to know through magazines that circulated in Bologna, such as the famous magazine "Emporium." In Morandi’s Portrait of His Sister (1912) the color palette is much darker and the brushstrokes certainly denser than in Derain’sSelf-Portrait (1913-1914) who instead used warmer tones and, unlike the Bolognese painter, the brushstrokes in this case are drier. If anything, the French painter’s influence on Morandi is indicated by the way the latter treated the anatomical part of the woman: the angular face is rendered through strong shading that evokes André Derain’s “Gothic” moment, as critic Giuseppe Raimondi pointed out.

The Still Life of 1912 was one of the first Italian receptions of the Cubist still lifes of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. What is striking is the color palette that characterizes Cubism, the absence of an obvious compositional axis and the, albeit slight, decomposition of the subject. A Still Life of a totally different style is that of 1919 (the date is given in the upper left corner). The composition of the subjects is already typical Morandi: unlike later still lifes, however, here it lacks that “dust” on the objects, as critics often call it. The pictorial rendering of the fruit, the bottle and the book aim to accentuate the volumes, while the plane on which they rest perfectly renders the depth in which the elements are placed.

In the late 1920s, Morandi came very close to metaphysics, although he never really adhered to it. One work, in particular, perfectly documents the pictorial language of this period and can be related to the works of Giorgio de Chirico and Carlo Carrà . It is Natura morta con manichino (1918): a mannequin, a characteristic element of de Chirico’s works, is depicted inside a box, representing the restlessness of the human being. The mannequin restores alienation and loneliness to the viewer, both states of mind emphasized by the bare pictorial space surrounding it.

In 1920 Morandi had the opportunity to see some of Cézanne’s works at the Venice Biennale, which led him to a more casual and natural painting, as in Landscape (1929) in which the subject matter becomes denser and the color testifies to the newfound landscape sensibility of his early youthful works. Still lifes, too, from the first half of the 1920s are modulated by chiaroscuro effects, the subjects dissolve into the environment, the sharp outline of the “metaphysical” works is missing, and the color range becomes richer, as in Still Life (1920). In this panel the artist focuses his attention on the natural datum of the subject; the lighter, blurred colors recall 15th-century frescoes.

In 1922 the magazine “Valori Plastici” closed, the disinterest on the part of Broglio (editor of the magazine) in Morandi’s works increased, and in 1924 at the Venice Biennale a classicist wind aimed at a "return to order" was blowing. All these elements led Morandi to realize how isolated he was from the Italian art world. During these years of neglect, the Bolognese painter devoted himself toengraving, which he had actually been practicing since attending the Accademia di Belle Arti in Bologna. Dropping almost completely into the art of engraving allowed Morandi to revolutionize the Italian printmaking tradition. The technique he favored was etching-that is, a technique based on engraving copper plate after it is immersed in nitric acid. The most important example for the Bolognese painter was Rembrandt, especially in terms of the rendering of tonal values as seen in Still Life with Bread Basket (1921) in which the objects are shaped thanks to the chiaroscuro effects of the burin (engraving tool). The Strada bianca (White Road ) of 1933 is one of many variations of Grizzana village in which the superimposition of signs defines the road. In general, it can be said that the link that unites painting and engraving is given by the tonal research that in painting is resolved with the variations of color while in engraving with the superimposition of signs. Engraving became, often, for Morandi as a moment preceding painting, to which he was particularly indebted towards the end of the 1920s. From 1934 is the work Landscape of Roffeno, a resort town of the artist. The canvas features a house in the center surrounded by surrounding vegetation, and on the horizon we see some mountains. The vegetation is made with an even and well spread out background while the large house is presented in all its volume. The canvas is dominated by the green of the trees framing the red and white of the building. Landscapes and still lifes became the artist’s stylistic signature: in fact, many canvases depict them, and this is due to the fact that Morandi did not want to “distract himself.” In other words, by depicting the usual subjects the painter was able to develop an artistic research aimed at their representation as the eye perceives them. Depriving the subjects of all futile decoration he analyzed them in every slightest variation of color or space. In the Still Life of 1960 the color is no longer compact, and it is always the variation of color that shows us that behind the subject there is a table and a wall. One of Morandi’s last works was Cortile di via Fondazza (1956) the house in Bologna, now become Casa Morandi, that the painter used as a home-studio. The view is realized with very light, warm colors overlaid by mellow, well-blended brushstrokes. The facade of the left house becomes almost an abstract plane, while the right side is dominated by the volumes of the houses defined by a light chiaroscuro. The meditation expressed in his works, the analytical gesture, and the search for almost perfect balance were all elements that made Giorgio Morandi one of the most original and independent artists of his period.

|

| Giorgio Morandi, Cortile di via Fondazza (1956; oil on canvas, 43 x 48 cm; Milan, Galleria d’Arte Moderna) |

The Morandi Museum in Bologna is the most important public collection dedicated to the painter. The museum came into being following a generous donation by his sister Teresa Maria Morandi. Until 2012, the museum’s home was in Palazzo d’Accursio, then it was transferred to MAMbo in Bologna, where it is also possible to see some of his etchings in addition to still lifes and landscapes.

Some landscapes, including Paese (1936), and a Natura morta (1946) are kept at the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome. Part of the Vitali collection (three landscapes and two still lifes) is kept at the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan. Also in the Lombard city, but at the Museo dei Novecento, which has also dedicated an entire room to the works of the Bolognese painter, one can admire his most emblematic work of the “metaphysical” period: Natura morta con manichino (1919). Other works are kept at the Galleria civica d’arte moderna e contemporanea in Turin and at Museo del Novecento in Florence, where Landscape (1936) and Still Life (1932-35) are part of the Alberto della Ragione collection. A number of Giorgio Morandi’s works are also preserved in Venice at the Galleria Internazionale d’arte moderna Ca’ Pesaro.

|

| Giorgio Morandi: the life and poetics of his works |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.