Important discovery comes from France, where 38-year-old archaeologist François Desset said he has succeeded in deciphering the linear script of the kingdom of Elam, a writing system used four thousand years ago at the civilization that developed in what is now western Iran and was first discovered in 1901 by a team of French archaeologists at the site of Susa, the ancient capital of the kingdom of Elam. The Elamite script is one of the oldest writing systems in the world, along with the proto-cuneiform in use in Mesopotamia and the hieroglyphs of the Egyptians, and the language of the kingdom of Elam, extinct for about two thousand years, is thought to be isolated, since it would not appear to be related to other languages of the Indo-European strain or to Semitic languages (an isolation that made everything more difficult). Desset, who works at Laboratoire Archéorient in Lyon, is a professor of archaeology at the University of Tehran and a visiting professor at the Department of Cultural Heritage, Archaeology and History of Art, Music and Film at theUniversity of Padua, made his discovery known in late November.

The Elamite script had thus been known for more than a century, but until now no one had understood the meaning of its signs. Desset’s work involved the most recent form of elamite writing,linear elamite, started in 2006 (“I did not wake up one morning and say I had deciphered linear elamite,” Desset told the French trade journal Sciences et Avenir, “but this work has lasted more than a decade and I was never sure I would reach the finish line.”), and was carried out using a method similar to the one the celebrated archaeologist Jean-François Champollion used to decipher hieroglyphics: Desset found the key in some repetitive texts and from there was able to make sense of the signs in the Elamite script. The French archaeologist, as mentioned, focused on the earliest known form of Elamite writing (this system was in fact in use roughly from 3300 to 1900 BCE. and underwent evolutions and modifications): it consists of forty inscriptions from the city of Susa, all written in linear Elamite (they are read from right to left and from top to bottom), which have the peculiarity (unique in the world for a language of the third millennium BCE) of being written in a purely phonetic script (i.e., similar to ours, where the signs correspond to consonants and vowels, and in the case of linear Elamite also to syllables).

|

| François Desset |

|

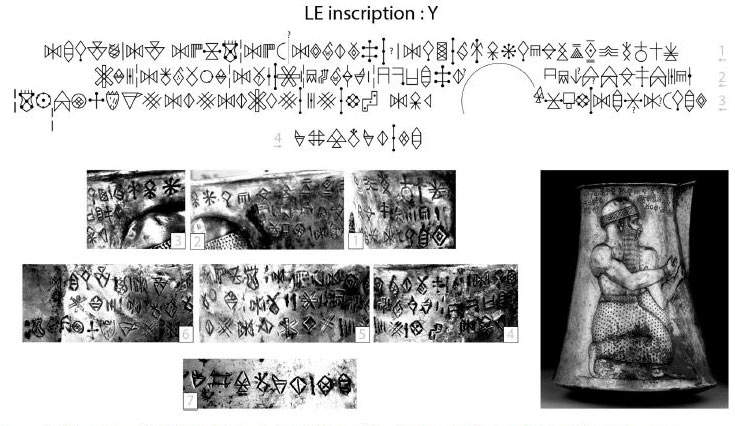

| Gunagi vase with “Y” inscription in linear elamite (Mahboubian Collection) |

|

| Diagram of the “Y” inscription |

The key to deciphering the Elamite script came from a corpus of 8 texts inscribed on 2000-1900 B.C.E. silver vessels called gunagi, from burials in the Kam-Firouz region and preserved at the Mahboubian Collection in London. These texts featured highly repetitive and standardized sequences of signs, which served, the archaeologist discovered, to define the names of two rulers, Shilhaha and Ebarti II, and the main deity worshipped in western Iran, Napirisha (the texts bear formulas such as "I am name, king of kingdom name, son of father"). Like Champollion, who started by identifying the names of the pharaohs, Desset identified the names of the Elamite rulers, and thanks to this evidence he was able to decipher the forty inscriptions, uninteresting in terms of content, the scholar noted, but extremely significant in allowing the meaning of the signs to be discovered. The first results will be officially published in 2021, in the German journal Zeitschrift für assyriologie und vorderasiatische archaeologie, but it will still take three years to complete the work, Desset predicts.

Desset’s work gives rise to important findings that, the University of Padua notes, may make it possible to write or rewrite entire pages of Ancient Near Eastern history of the late 3rd millennium BCE. Moreover, several clues about the origins of this writing (which, moreover, is the oldest known phonetic writing), which may be much more remote than hitherto thought, put in a different light the traditional idea that Mesopotamia was the only land of invention and dissemination of writing (in fact, the scholar believes that Mesopotamian and Elymian writing were contemporaneous: “the two writings,” he said, “are not mother and daughter, but are sisters. This completely changes the perspective on the phenomenon of writing in the Ancient Near East and its understanding.”). The implications are extremely relevant, Desset explained, “for the development of writing in Iran and in the Ancient Near East in general, for considerations of continuity between the Proto-Elamite and Linear Elamite writing systems, for the Elamite language itself, which is better documented in its earliest form and thus made accessible for the first time through a writing system other than Mesopotamian cuneiform.” But that’s not all: until now, Desset said, “everything about the people who occupied present-day Iran came from Mesopotamian texts. These new discoveries will give us access to the point of view of the men and women who occupied a territory they designated as Hatamti, since the land of Elam as we know it only corresponds to a foreign geographical concept formulated by their Mesopotamian neighbors.”

Archaeologist Massimo Vidale of the University of Padua, on the other hand, said that “France, for this new work of decryption, maintains its primacy in understanding lost ancient writing systems!” Desset’s work (who outlined his discovery in a video interview with Francesco Suman for Il Bo Live, the magazine of the University of Padua) will soon continue with an attempt to decipher the oldest form of elamite, the proto-elamite, for which, he notes, “a highway has now opened.”

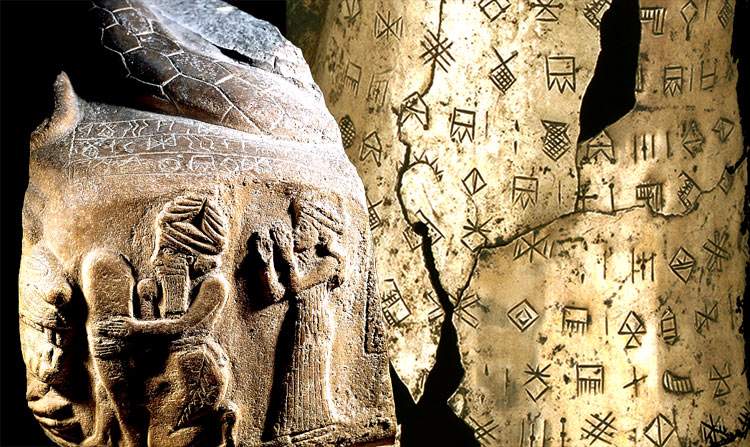

Pictured: “inscription B” in linear elamite (2150-2100 B.C.) and “inscription K” in linear elamite (1900-1800 B.C.).

|

| “B” inscription in linear elamite on an engraved stone from Susa, dating from 2150-2100 BC and preserved in the Louvre |

|

| One of the gunagi vases in the Mahboubian collection, with the inscription “Z” |

|

| France, 38-year-old archaeologist deciphers linear elamite, a 4,000-year-old script |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.