We receive and publish the following review of the Caravage à Romeexhibition currently underway at the Musée Jacquemart-André in Paris.

In its essentiality, a high-level exhibition. This is what can be said in two words about Caravage à Rome, curated by Francesca Cappelletti and Pierre Curie, although the subtitle(Amis et ennemis), which recalls something already heard, implicitly declares how novelty should not be expected at all costs, in terms of acquisitions on the scientific level. The exhibition, in fact and first of all, finds one of its reasons precisely in exhibiting in Paris, which had not hosted an event of comparable object since 1965. Other times: at the Louvre, Caravage et la peinture italienne duXVIIe siècle could bring to the public masterpieces by Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610) now as immovable as the paintings of the Contarelli chapel; and even the Nativity of Palermo, sadly taken away there a few years later.

This time, the venue, the Musée Jacquemart-André, turns out to be less known to most and partly unexpected: within the collections, precisely the period between the 16th and 17th centuries is less represented (’void’ which the exhibition can be said to make up for, in some ways). But this matters little, beyond the fact that the exhibition spaces are collected and this has a reflection, more than on the fruition, on the limited number of works per room: some sections are represented, however and always effectively, even by a couple of paintings. Moreover, the Jacquemart-André’s willingness to make itself a venue for the event was rewarded in particular with three major loans (two Caravaggios and a Baglione) from Palazzo Barberini, which in parallel with six works from the Parisian museum set up the exhibition The Mantegna Room.

But returning to Caravage à Rome, it is characterized by being developed by themes, as many as eight: The Theater of Severed Heads; Music and Still Life; Painting with the Model Ahead; Contemporaries; Images of Meditation; Faces of Rome in the Early Seventeenth Century; The Passion of Christ, a Caravaggesque theme; and The Escape. This, nonetheless, gives occasion to address questions of chronology (a criterion of presentation perhaps more commonly adopted), beginning with the opening ’piece’. Like (and in some ways in contrast) with the Milanese Dentro Caravaggio, in the first room the Palazzo Barberini’s Judith and Holofernes makes a fine showing, here re-proposed to c. 1600, slightly tweaking the traditional dating that would have it slightly earlier, but in Milan assigned to 1602 according to a document that has now been more carefully reread (an aspect that is not, however, dissected in the catalog).

|

| Caravaggio, Judith and Holofernes (1602; oil on canvas, 145 x 195 cm; Rome, Gallerie Nazionali dArte Antica di Roma, Palazzo Barberini) |

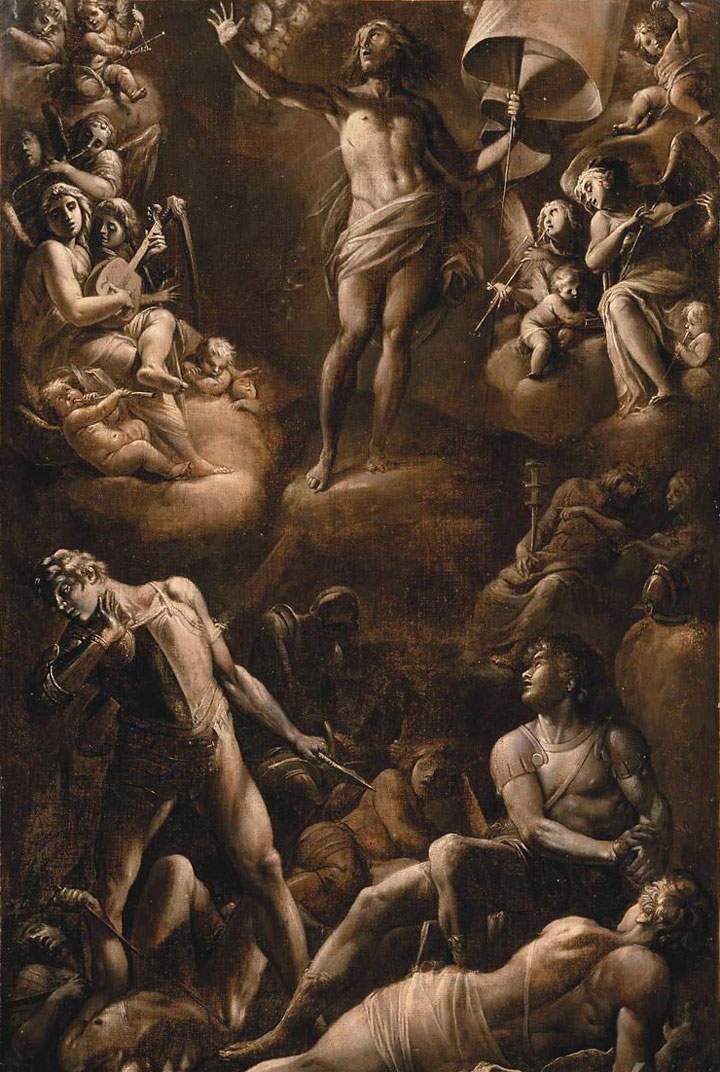

But beyond that, from that exceptional loan an exciting art-historical and narrative journey starts and unfolds, among more or less known and seen masterpieces. Among the latter, it is worth mentioning the magnificent Saint John the Baptist by Bartolomeo Manfredi (Ostiano, 1582 - Rome, 1622) from the Louvre. And also from the same museum site, interesting more for historical reasons than for the artifact itself, is Giovanni Baglione ’s (Rome, 1566/1568 - 1643) monochrome sketch of the lost (except for two surviving pieces) Resurrection of Christ from the Gesù Church. A work, the latter, that inflamed an unparalleled rivalry between the Roman painter and Merisi, a biographical (and other) aspect relevant in the more general context of the relations between artists of the time, with the singular presence of the ’master without pupils’ Michelangelo Merisi.

A strong point of the exhibition is the well-researched and value-packed juxtaposition between some works. Such as that between Baglione’s Baptist and Caravaggio’s similar subject in the Capitoline version. Or again between Caravaggio’s Saint Lawrence by Cecco and Merisi’s Saint Francis in Meditation by Cremona. Still by the latter, Genoa’sEcce Homo near the same subject painted by Ludovico Cardi known as il Cigoli recalls an anecdote that would have seen a dispute between the two artists.

|

| Bartolomeo Manfredi, Saint John the Baptist (1613-1615; oil on canvas, 148 x 114 cm; Paris, Louvre). Photo by René-Gabriel Ojéda |

|

| Caravaggio, Saint John the Baptist (1602; oil on canvas, 129 x 94 cm; Rome, Capitoline Museums, Pinacoteca Capitolina) |

|

| Giovanni Baglione, The Resurrection of Christ (1601-1603; oil on canvas, 86 x 57 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

But over all, the comparison that alone is worth the visit is the one between the two debated Magdalene in Ecstasy: the already known version formerly in the Klain collection, and the one recognized in 2014 by Mina Gregori at a private Dutch dealer. Two pictorial texts on which the connoisseur’s eye is finally exercised jointly (so far, outside its Swiss vault, the new canvas has only been seen in Tokyo). The critical debate is open, all the more so since, individually, the catalog essentially takes no position, although to finish the exhibition somewhat credits both editors (and so the number of Caravaggios featured reaches the remarkable round number of twenty). So far, in scholarly circles, very few have come to oppose Gregori’s attributive hypothesis. And it does not help in the face of such hesitation the failure to reproduce an ancient tag that would assign the canvas to Merisi, specifying in a few lines, precisely in addition to the author, subject, coeval location and ultimate recipient (name and city).

An unexpected completeness of information that, moreover, had already raised suspicions about the document’s authenticity. To that consideration we would like to add here the observation that a skull like that (by chromaticity, if at least a ’joke’ is permissible, closer to a brass knob!) appears foreign to Merisi’s production (if only to that known). In any case, returning to chronologies, 1606 is dubiously proposed for this work, although mentioning the recently proposed 1610. This is no small matter, considering also that the exhibition is dedicated to Caravaggio’s Roman years. At the same time, the chronological cut adopted (which, for Caravaggio, but not for his followers, stops at 1606, the year in which he leaves the Eternal City forever) justifies the absence of works such as the St. John the Baptist Borghese and the St. Ursula both from 1610, which would certainly have been the most pertinent by juxtaposition to confirm (or disprove) a later dating for the Magdalene.

|

| Caravaggio, Magdalene in Ecstasy known as Magdalene Klain (post 1606; oil on canvas, 106.5 x 91 cm; Rome, private collection) |

|

| Caravaggio, Magdalene in Ecstasy (post 1606; oil on canvas, 103.5 x 91.5 cm; Netherlands, private collection) |

Appreciable, finally, is the fact that, in antithesis to often unscrupulous movementist logics that affect exhibitions, the three Caravaggios in the Louvre have remained there (but then again, it has been 20 years since any of them have been absent from the Grande Galerie). Those who would like to see them can always go to the museum that holds them, an additional and always valid reason to visit the city (and all the more so for visitors to Caravage à Rome), which at this time thus finds itself hosting an exceptional number of Merisi’s works.

Also of note is the conference Caravaggio. A Baroque Life, a side event held on January 9, where for the first time the scientific investigations carried out on the ’Gregori’ Magdalene were illustrated and compared with those on the other version. Last but not least, those visiting the Jacquemart-André between now and Jan. 28 will find there the Hermitage’s Lute Player, which is being presented to the public for the first time after a lengthy restoration.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.