Sicily also restarts. On Feb. 16, the exhibition Terracqueo, curated by the Frederick II Foundation, reopened. The Royal Palace of Palermo continues to be a symbol, as it was in ancient times, of coexistence among the peoples of the Mediterranean. After the exhibition Castrum superius and the installation Acqua passata¿ by Cesare Inzerillo with which this coexistence was recounted, without rhetoric, in its most dramatic dimension, in memory of the tragedy of October 3, 2013 in which 366 men, women and children of Eritrean nationality Eritrea lost their lives 800 meters from Lampedusa’s Rabbit Island, with the new major exhibition, whose closure has been extended until May 31, the Frederick II Foundation keeps its promise of a cultural project endowed with long-term coherence.

At the center of the exhibition is the Mediterranean, a whole, where “every artifact from the sea,” notes Patrizia Monterosso, general director of the Foundation, “tells the stories of life on land, and every artifact from the land tells the stories of the sea.”

Sea. Land. And sky. In the exhibition’s icon, an overhead “eye,” like the one in Andrea Mantegna ’s Bridal Chamber in Mantua that pierces the center of the vault and lets “the sky into the room,” makes the air and clouds look out from a sea vortex that pushes up, in a motion of elevation that recalls another masterpiece: theAssumption of the Virgin by Correggio, with its extraordinary spiral of bodies soaring. Because the Mediterranean must be “understood” from the sea, from the land, but also from above, as in Folco Quilici’s unforgettable series L’Italia vista dal cielo (Italy seen from the sky ), which for Sicily had Leonardo Sciascia as co-author of the text.

Understanding the Mediterranean. In the intentions of those who conceived it, this exhibition (which does not have a curator, as per the Foundation’s new course, but a collegial curatorship that coincides with the scientific committee) is to go beyond the objective reality of the 324 artifacts: “Terracqueo,” Monterosso further says, “is a tale of the true soul of the Mediterranean, from geology to myths, from Greek colonization to the Phoenicians, from trade to modern-day globalization.”

An unprecedented “experiment,” one would say, is what the Foundation has been working on for the past few years, as if it were a single project that articulates and declines over time in new forms, enriching itself. Thus, the discourse opened with the aforementioned installation Acqua passata¿, on the drama of migrants who lost their lives in the waters of the Mediterranean, is re-engaged in the exhibition in the “prelude” that leads to the Duca di Montalto exhibition rooms. It is in the medieval corridor that precedes them that we find, in fact, the theme of shipwreck in a video installation (Teichos, Services and Technologies for Archaeology, Salvatore Agizza and Federico Baciocchi) that reproduces the 8th-century B.C. Crater. C. found on Ischia inside a tomb in the San Montano necropolis. The details, flowing enlarged on the walls of a niche, lead back to the dichotomous meaning of the sea, as a place of hope to land in a new land, where to build a better future, or an abyss in which dramatic shipwrecks take place.

|

| Palazzo dei Normanni, exhibition venue |

|

| Entrance to the exhibition, medieval corridor with multimedia projections |

|

| Exhibition hall |

|

| Exhibition hall |

|

| Exhibition hall |

A continuity underscored by Federico II Foundation President Gianfranco Miccichè, who recalled how “the cultural events proposed over the past two years have not failed to promote a culture of peace and education for nonviolence, to foster Sicily’s natural vocation of symbolizing a ’bridge of peace’ between all the peoples of the Mediterranean Sea.” “Every artifact of Terracqueo,” the president further said, “contributes to showing the Mediterranean as the greatest factory of ideas in the world: from philosophy, to art, to science, to medicine, to political organization, everything contributes to the achievement of principles without barriers and without prejudice.”

But back to our “prelude.” Among the key moments of an exhibition is undoubtedly that at the beginning of the journey. It is here that those who curate the exhibition must be able to overwhelm, to invest the visitor with sensations, staging a rite of passage that gradually is able to trigger the rêverie, the daydream, as the condition of those who leave behind the dross of the present to immerse themselves in abandonment in the “apart” space of history and art.

This is especially true of Terracqueo. The visit begins precisely as “a dive” into an aquatic corridor (multimedia set-up is by Sinergie Group based on the Foundation’s idea). Amidst kaleidoscopic seabeds, aided by the natural slope of the floor, rather than approaching, it really seems to flow, carried along by the flow, toward the large exhibition hall.

Before accessing it, the polar star of the exhibition, theFarnese Atlas, a marble masterpiece dating to the second century A.D., on loan from the MANN, National Archaeological Museum of Naples, thanks to the sober setting of a curved backdrop with a giant illustration of the details of the globe it holds, seems to symbolically embrace the visitor to lead him or her on an evocative route between past and present.

Perhaps originally placed in the Library of the Forum of Trajan in Rome, the statue of the mighty titan Atlas kneeling under the weight of the globe is certainly derived from a Hellenistic-era original. The anatomy of the torso is identified in the individual muscle tensions (head, arms and legs are due, however, to the restoration of Carlo Albacini), just as detailed are, on the sphere, the oldest depictions of the celestial vault and the Zodiac that have come down to us with the coluri, that is, the lines of the meridians passing through the poles. Art historian Giovan Battista Scaduto has juxtaposed (in the catalog) with the Farnese marble one of the Labors of Hercules painted by Giuseppe Velasco, in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, in the room where the Sicilian Parliament still meets today. Here appears, precisely, the one in which the mythological hero holds, instead of Atlas, the celestial sphere.

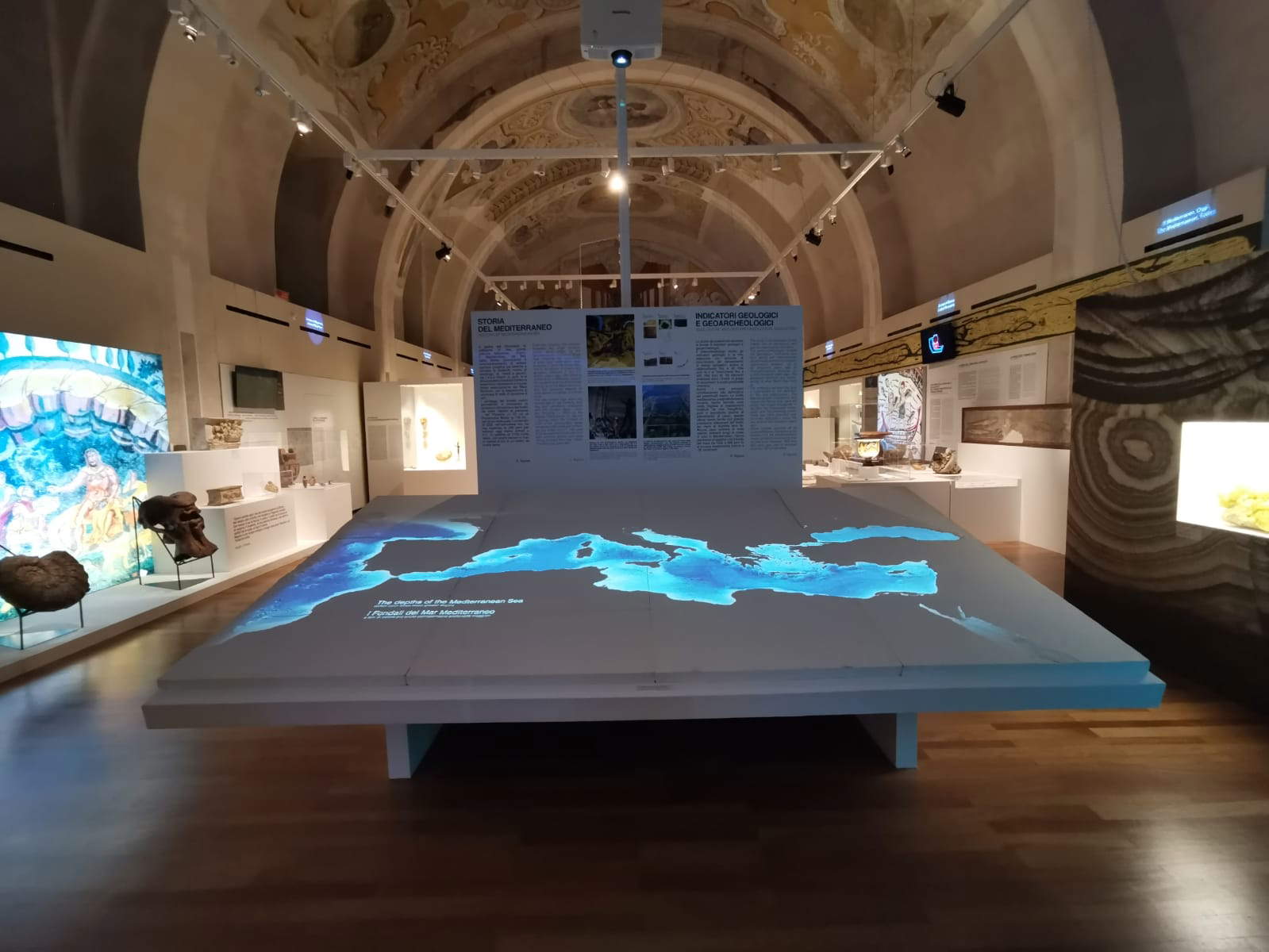

Leaving, then, the titan behind, the captivating game of staging begins, which, if it were a rhetorical figure, we would call oxymoronic: the actual path of the exhibition, which has a decidedly didactic slant, begins with a large interactive solid (made by TEICHOS in collaboration with the University of Bari “Aldo Moro,” ENEA and INGV), which, however, at the same time that it provides information (on the geological evolution that has affected the Mediterranean) conceals others. The back of the solid, in fact, barely allows a glimpse at a distance of the various objects and works displayed behind it in the large hall. To the benefit of the curiosity piqued right away in the visitor.

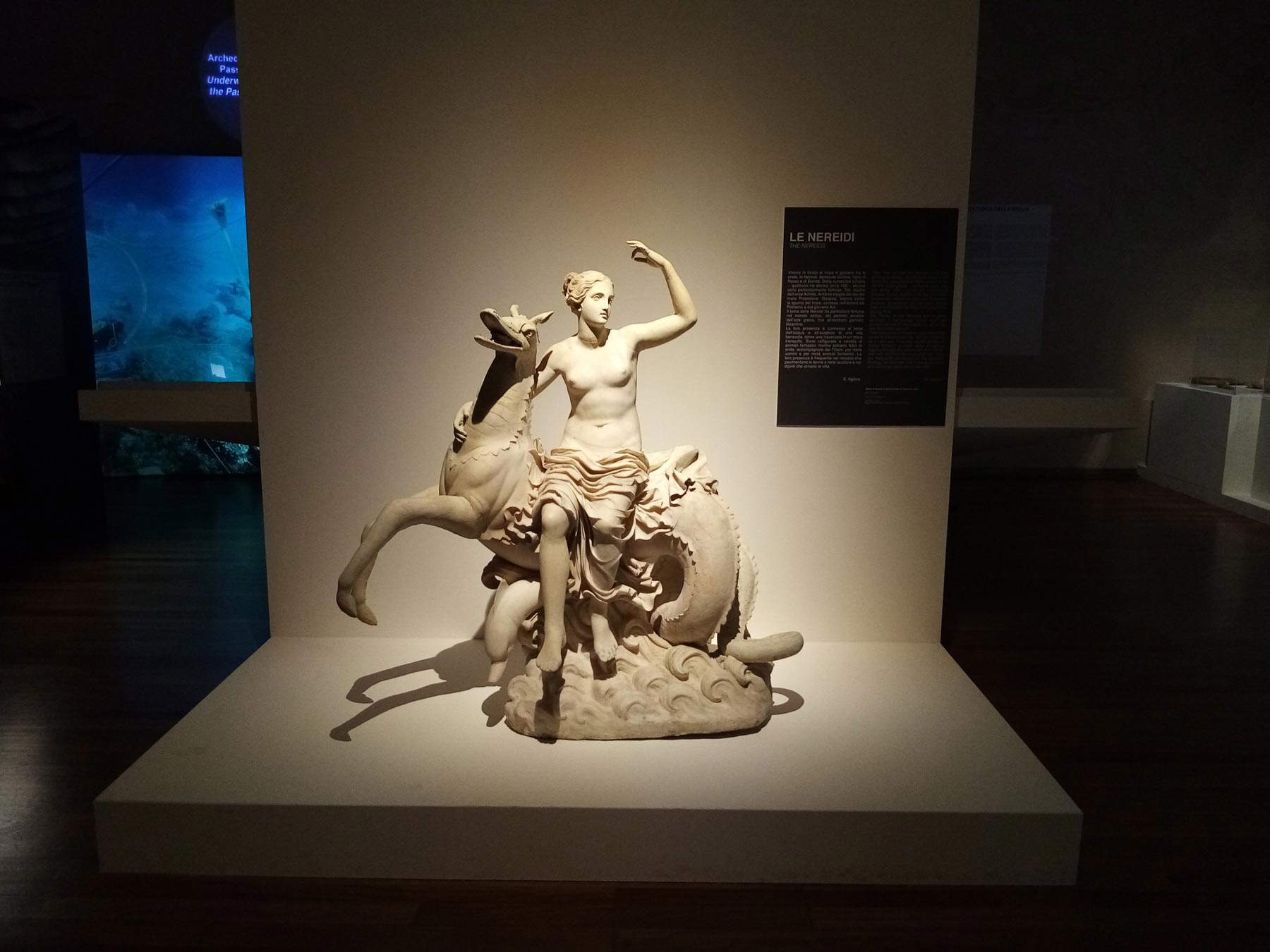

But not only that not everything there is to see is immediately made visible. The surprise effect is literally just around the corner. A translation in exhibition terms of Augustine’s “vela faciunt honorem secreti” (Serm. LI, 5), whereby “precious” things are to be concealed from view, behind the solid is the other masterpiece on loan from the MANN, the Nereid on pistrice, from the early decades of the first century AD. A.D. It was found in 1841 in the villa that Publius Vedius Pollonius had built on the hill called Pausilypon (which frees one from distress), now Posillipo, where it was probably placed in a nymphaeum or inside thermal rooms on the villa’s upper terrace. The pride of the Mann’s collections, the exquisite statuary group depicts a Nereid, a sea nymph daughter of Nereus, on pistrice or “ketos,” a hybrid sea monster with the head of a dragon, the body of a horse, and the back and tail of a sea serpent. The work constitutes a “unicum” in ancient plastic, as no comparable patterns can be recalled; the possibility that it may derive from a 4th-3rd century B.C.E. Hellenic model of scopadean derivation is also excluded.

|

| The interactive solid |

|

| The Farnese Atlas in the exhibition layout |

|

| Roman art, Farnese Atlas (2nd cent. AD; marble; Naples, National Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Roman art, Farnese Atlas, detail |

|

| Roman art, Nereid on pistrice (early decades of 1st cent. AD; marble; Naples, Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Roman art, Nereid on p istrice (early decades of the 1st cent. AD; marble; Naples, Archaeological Museum) |

The contrast between the impetuous motion of the animal on one side and the nymph riding it with graceful steadiness is splendid. The pistrice is stopped in the act of dominating the billows, its muscular legs in a rampant stance, its tail twisted in mighty coils and its upper part with a twist that continues upward into its outstretched neck and wide-open snout to emit a roar as if held back in the silence of the abyss; the sea nymph, in contrast, sits as if on the back of a horse on a quiet rural stroll, fronted with both legs left hanging over the side of theanimal, to whose neck she barely holds on with one hand (the arm is a nineteenth-century remake), that is, without clinging (as, on the other hand, it seemed to Armando Cristilli, 2006) as the impetus of the beast would require; and defying the laws of balance she gracefully raises her other arm, sure she will not be unhorsed. Let us even say that the nymph is not really “going along with the movement” of the beast (Cristilli again). She looks serenely away, turning her head in the opposite direction to that of the sea monster; oblivious to the “hic et nunc,” were it not for that drape that dripping with water adheres to her legs, rising just slightly in folds that thicken neatly to leave one above the knee uncovered, then unfolding on the animal’s side and back with a whimsy of swirls that one would say is mannerist. Also strong is the other contrast between the rippling, if disciplined, undulations from which the marine pair emerges and the delicate plastic accentuation of the smooth limbs of the Nereid. The exhibition is also an opportunity to rediscover this work of art after its cleaning, carried out by Lorella Pellegrino of the Centro per il Restauro di Palermo, as part of agreements with the lending Neapolitan museum (the intervention also involved the Farnese Atlas).

We return, then, to the beginning of the itinerary, from which the Nereid has not yet revealed itself to the visitor. This is the starting point for the eight sections into which the exhibition is divided: “A Sea of History,” “A Sea of Migration,” “A Sea of Trade,” “A Sea of War,” “A Sea to Navigate,” “A Sea of Resources,” “Underwater Archaeology: Past and Present,” “The Mediterranean. Today.”

The individual sections, without barriers or sharp breaks within the greater environment, equally allow at all times by the visitor not to lose track of the topography within which he moves.

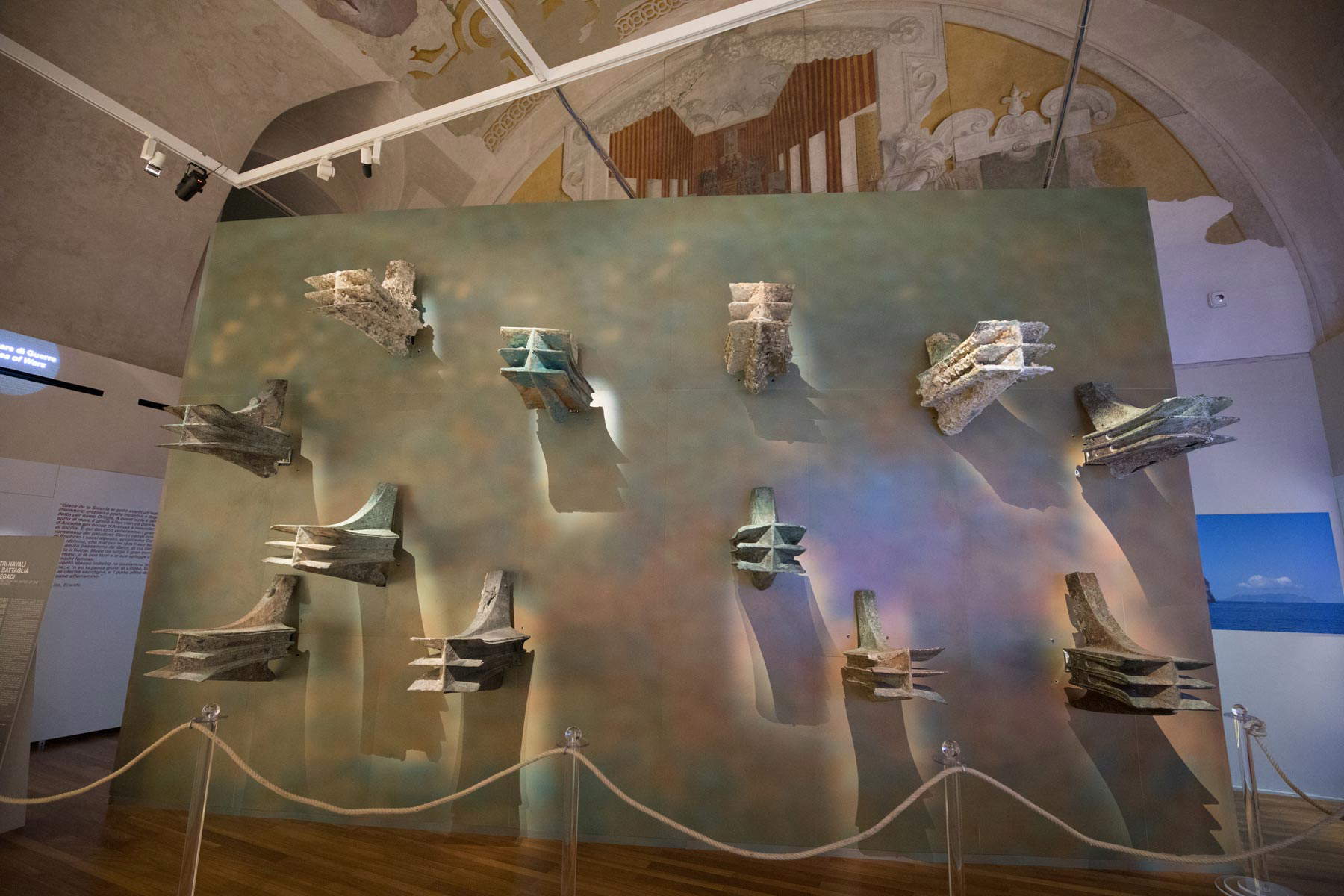

Avoiding a disorienting labyrinthine connotation, certain moments of the narrative have been cleverly selected, such as the large wall, with twelve rostrums on several levels, which picks up the same tones of oxidized bronze, but which are also those of the sea waters, contributing to the perception of the looming of an armed fleet and death in the midst of a naval battle. The result of the ensemble goes far beyond documenting how advanced military technology at sea was in those days to become almost a contemporary art installation. This effect would not have been achieved if the retaining wall had been neutral. Behind it, the visitor is called to walk through a short interactive tunnel in which those rostrums return to ply the seas menacingly, reassembled in digital restorations of ancient warships.

The exhibition, in general, achieves a delicate balance between the order required by the didactic setting and the overlapping of the contents , which are indeed many, thanks to a studied proxemics that allows various distances of enjoyment of the objects to be observed, in a calibrated relationship between the whole and the detail.

Other pieces worth mentioning are the Louterion found in the wreck of Panarea III, which confirms the presence on board of altars intended for propitiatory rites related to navigation; or the Tuna Vendor Crater, datable to the first half of the 4th cent. BCE. in an area that one is inclined to locate in Sicily, which reveals a highly topical scene, recurring even in today’s local markets, and testifies to the perpetuation of ancient traditions to the present day: a fish seller is slicing a tuna on a stump and the buyer to conclude the purchase is provided with a coin.

|

| The rostrums |

|

| Crater of the tuna seller |

|

| Display case with clay Deinos in the center depicting triskelés, indigenous production (late 8th cent. BCE; Agrigento, Griffo Archaeological Museum) |

|

| The proeections of Lucia Cantamessa’s shots in the section dedicated to the Mediterranean today |

|

| The proeections of Lucia Cantamessa’s shots in the section dedicated to the Mediterranean today |

|

| The section “A Sea to Sail.” |

Special prominence in the itinerary is given to the Battle of the Egadi, a cue to learn about military techniques and strategies, but also a way to study life on board not only in peace but also in war. Above all, a tribute to former councillor Sebastiano Tusa who fatally lost his life in 2019 on that same day, March 10, of the naval battle in 241 B.C. in which the Romans defeated the Carthaginians and to which he made a fundamental contribution of studies as an archaeologist.

Approaching the end of the itinerary, in a separate room, the floor becomes “liquid” again in a new installation, and the walls become “shores” in which the thousand faces of today’s Mediterranean are projected, stopped in the reportage made along seventeen countries by journalist Carlo Vulpio and photographer Lucia Casamassima.

The exhibition closes with a section devoted to underwater archaeology and the countless finds that are due to the Superintendence of the Sea, Tusa’s “creature.” And the words of another of the fathers of underwater archaeology, George F. Bass, come to mind: “If it were not for Sicily, I would not be a marine archaeologist. If it weren’t for Sicily, I wouldn’t even be an archaeologist.”

The Terracqueo exhibition project was born in the larger framework of collaboration between the Frederick II Foundation, the Department of Cultural Heritage and the Regional Center for Restoration, with numerous regional and civic museums, superintendencies, and national museums such as the Mann, the Capitoline Museums, and the Etruscan Museum of Volterra. As well as collaboration with the University of Palermo’s Sistema Museale di Ateneo and from the “G.G. Gemmellaro” Museum and the Sicily Foundation, Mandralisca Foundation and Whitaker Foundation.

As we recalled, the exhibition has no curator, but a collegial curatorship to which important scholars contributed, including Luigi Fozzati, Massimiliano Marazzi, Valeria Li Vigni Stefano Medas, Marco Anzidei, Ignazio Buttitta, Carlo Beltrame, Carla Aleo Nero, Babette Bechtold, Giulia Boetto and Marilena Maffei.

But this is not the only special feature of a Foundation that pulls itself out of the chorus. Maria Elena Volpes, a member of the Foundation’s Board of Directors and former general manager of the regional Department of BBCC, points out in the catalog the countertrend course: “the Foundation has said strong no to that marketing of selling exhibitions in Italy that has often ended up commercializing many of them.” We could call it an “autarkic” entity: “organizer and creator of the exhibitions,” Volpes further explains, “it takes care of communication, fruition, merchandising related to each individual exhibition and is also Publisher of volumes and catalogs.” Like that of Terracqueo, a scholarly sylloge of essays intended for specialists, but not only.

The author of this article: Silvia Mazza

Storica dell’arte e giornalista, scrive su “Il Giornale dell’Arte”, “Il Giornale dell’Architettura” e “The Art Newspaper”. Le sue inchieste sono state citate dal “Corriere della Sera” e dal compianto Folco Quilici nel suo ultimo libro Tutt'attorno la Sicilia: Un'avventura di mare (Utet, Torino 2017). Come opinionista specializzata interviene spesso sulla stampa siciliana (“Gazzetta del Sud”, “Il Giornale di Sicilia”, “La Sicilia”, etc.). Dal 2006 al 2012 è stata corrispondente per il quotidiano “America Oggi” (New Jersey), titolare della rubrica di “Arte e Cultura” del magazine domenicale “Oggi 7”. Con un diploma di Specializzazione in Storia dell’Arte Medievale e Moderna, ha una formazione specifica nel campo della conservazione del patrimonio culturale (Carta del Rischio).Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.