by Ilaria Baratta, published on 10/03/2019

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Water Horizons Between Painting and Decorative Arts. Galileo Chini and other protagonists of the early 20th century" at the Palazzo Pretorio in Pontedera, from December 8, 2018 to April 28, 2019.

Have the decorative arts always played a lesser role than the fine arts in the course of art history? To answer this question, consider the general reform movement that developed in Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century: this aimed to retrain the decorative arts that had long been subject to the culture of historicism. Thus, in England, theArts and Crafts movement was born as a result of the high level of industrialization that the nation had reached and thus saw the value ofcraftsmanship gradually being undone: new aesthetic values would save craftsmanship and lead the decorative arts to liberation from perennial inferiority to painting, sculpture and architecture. At the same time,Art Nouveau emerged in France, which brought the decorative arts to its peak by using materials such as glass and ceramics; thegoldsmith’s art also reached a high level of quality.High quality was accompanied by refinement, introducing naturalistic motifs including flowers, leaves and animals into the decoration of these materials. In Germany the Jugendstil, characterized by sinuous calligraphic lines, developed, while in neighboring Vienna that celebrated artistic movement known as the Viennese Secession, declined in the second half of the 1890s, declined more on geometric motifs than typical naturalistic forms, an aspect that was later adopted by Germany as well.

In this climate of European renewal, Italy was in a decidedly backward position, as can be read in the pages of the magazine Emporium, which, on the occasion of the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1900, stated, “to apply oneself to the industrial arts was pe’ our artists, until a few years ago, a demerit or at least an impropriety. [...] Without pride or pomp, it must be acknowledged that the shining example of some foreign artists-especially English ones, Morris hopes-has brought us to our senses in time.” Indeed, credit for welcoming this modern artistic reform in Italy, affirming equal importance to the decorative and figurative arts, was due to the Florentine artist Galileo Chini (Florence, 1873 - 1956). Believing and recognizing that ceramics played a significant role, especially for his land, in 1896 he founded, together with Vittorio Giunti, Giovanni Vannuzzi and Giovanni Montelatici, theArte della Ceramica, a small ceramic art factory that quickly achieved considerable success, thanks to theinnovation that characterized products commonly made from a material already typical of Florentine manufacturing. The handicrafts that came out of theArte della Ceramica (recognizable by the symbol of the pomegranate, a wish for success and fertility, and by two small hands intertwined to indicate the fraternal bond between the enterprise’s members) were thus assimilated in originality and quality to the general modernist movement that had been developing in Europe for a few decades by then.

Galileo Chini’s artistic activity, which began precisely in Florence from the founding of his Arte della Ceramica, but which took him to Venice, Montecatini, Salsomaggiore, Viareggio and even Bangkok, is retraced at every stage in the accurate exhibition that PALP in Pontedera dedicates to him until April 28, 2019, entitled Orizzonti d’acqua tra pittura e arti decorati. Galileo Chini and other protagonists of the early 20th century. Through this exhibition and its rigorous catalog, curator Filippo Bacci di Capaci is convinced that the figure of the artist gains vigor and is restored to its completeness, revealing its international dimension. With this monographic exhibition, curated by Maurizia Bonatti Bacchini and Filippo Bacci di Capaci, it is intended to offer a useful and additional piece to a serious critical review of this great interpreter of the early 20th century in Italy.

As can be seen from the very title of the exhibition, the curators have chosen to present Galileo Chini’s art to the public by following the theme of water, a constant element in his production: in many of his paintings (for he did not deal only with ceramics) he depicted the sea of Viareggio, the Arno, the waters of Venice, the canals of Bangkok, and worked for a long time in famous spas, such as Salsomaggiore and Montecatini. Central to his art, therefore, are water and water life with its fish and marine life, largely represented in his ceramics; the Venetian lagoon, which he reached during the Biennales, whose installations he curated on several occasions, the Tyrrhenian coast, the Fossa dell’Abate area in Viareggio, and the oceans he ploughed on his journey to Siam, where he was fascinated by the stupendous sunsets over the water, can be recognized in his paintings. Through the common thread of water, it is possible to traverse not only the different vistas he saw and the places he visited or stayed, but also the various artistic currents the artist approached in the course of his work: Symbolism, Divisionism,Orientalism and the Viennese Secession, the latter with particular reference, despite his personal reinterpretation, to Gustav Klimt (Baumgarten, 1862 - Vienna, 1918).

The Pontedera exhibition was also set up by juxtaposing the paintings and drawings with ceramic works, allowing visitors to understand, in a rather careful and timely manner, the connection between one and the other, thanks also to the presence of studies for the decoration of ceramic artifacts displayed in the same room. An innovative aspect and characteristic of the ceramics designed by Galileo Chini is the correlation between structure and decoration. The decorative composition is not just an embellishment of the material, but is studied according to the conformation of the object’s structure: for example, larger and wider figurative elements are placed where the object’s outline expands, on the contrary thinner and smaller elements appear where the outline narrows. The exhibition itinerary has been meticulously designed in detail: in some cases, especially in the last rooms, the visitor finds himself immersed in enveloping environments, almost forgetting that he is in a museum, thanks to the care with which the colors, upholstery and even the plants have been chosen. The different sections that follow chronological and stylistic order also turn out to be well defined.

|

| Hall of the exhibition Water Horizons between Painting and Decorative Arts. Galileo Chini and other protagonists of the early twentieth century |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Horizons of water between painting and decorative arts. Galileo Chini and other protagonists of the early twentieth century |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Horizons of water between painting and decorative arts. Galileo Chini and other protagonists of the early twentieth century |

|

| Hall of the exhibition Horizons of water between painting and decorative arts. Galileo Chini and other protagonists of the early twentieth century |

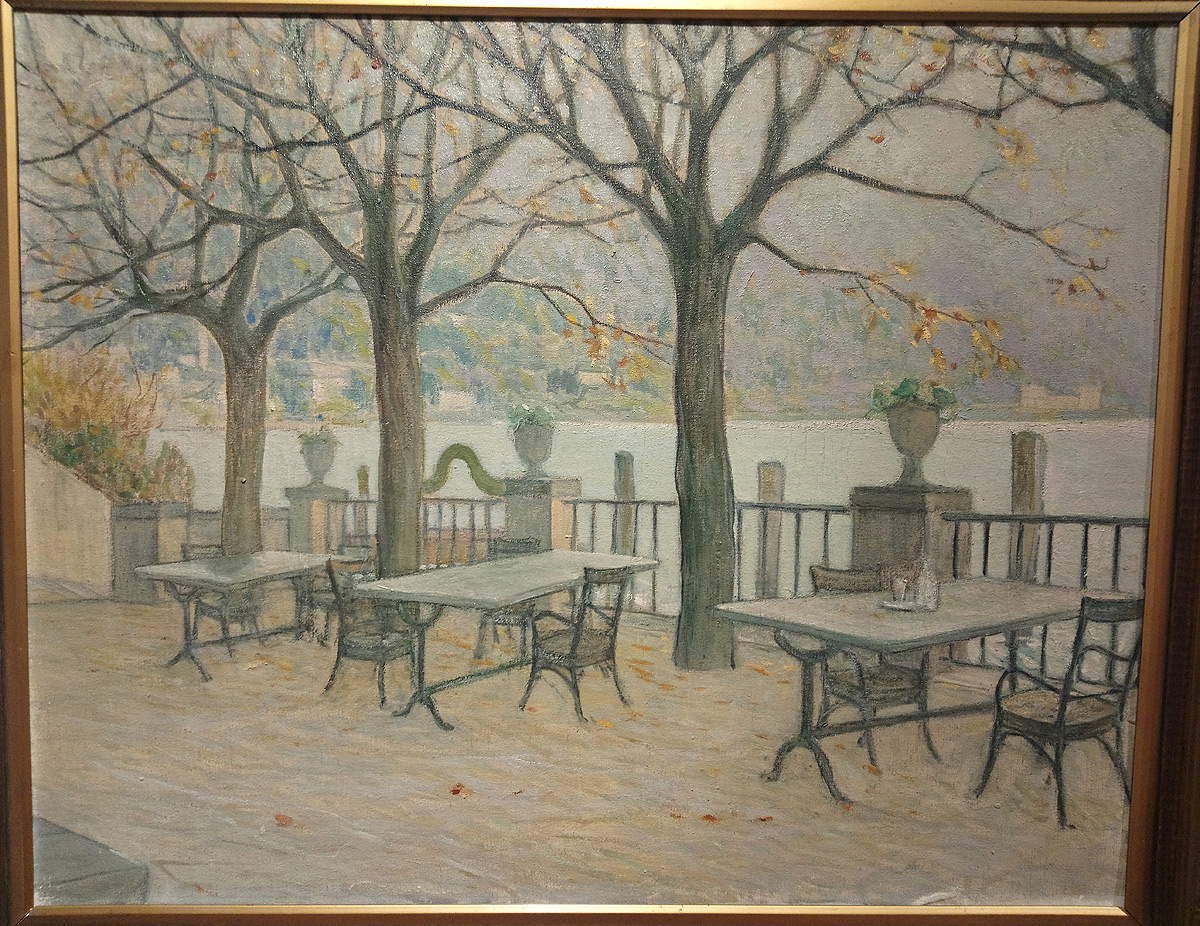

The exhibition opens with The Stillness, a 1901 painting presented at the 4th Venice Biennale that depicts an autumn landscape with birch trees; particular is the decision to focus on the trunks of the trees, cutting into the image their foliage. The canvas is significant because it marks the beginning of his long presence at the famous Venetian event and puts the emphasis on his Divisionist beginnings, drawing on the painting of Giovanni Segantini (Arco, 1858 - Mount Schafberg, 1899), one of the greatest exponents of Divisionism, that artistic movement characterized by theapplication of color on the canvas in small strokes and the desire to represent the real and the effects of sunlight especially on the landscape. Indeed, see in The Stillness the reflections in the water and the shadows of the trees on the different shades of green of the grass. In the same year Auguste Rodin (Paris, 1840 - Meudon, 1917) gave Chini a plaster study of Danaide, which is featured in the exhibition. The maiden, one of Danao’s daughters, is portrayed as she is slumped to the ground, exhausted from the eternal sentence imposed by Zeus to fill a bottomless jar.

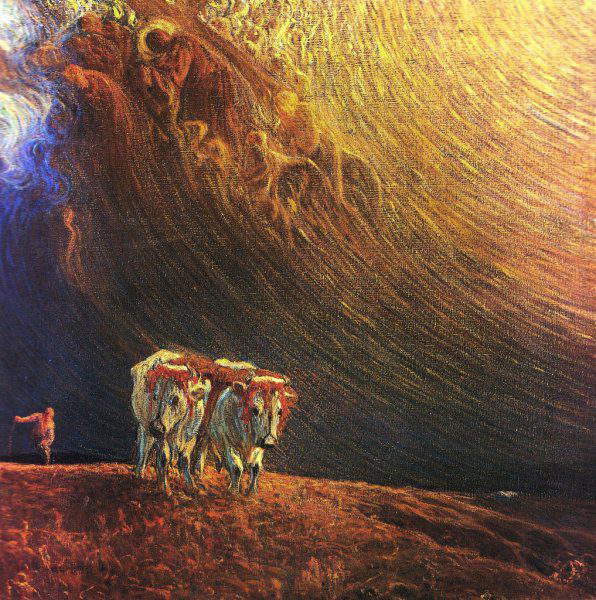

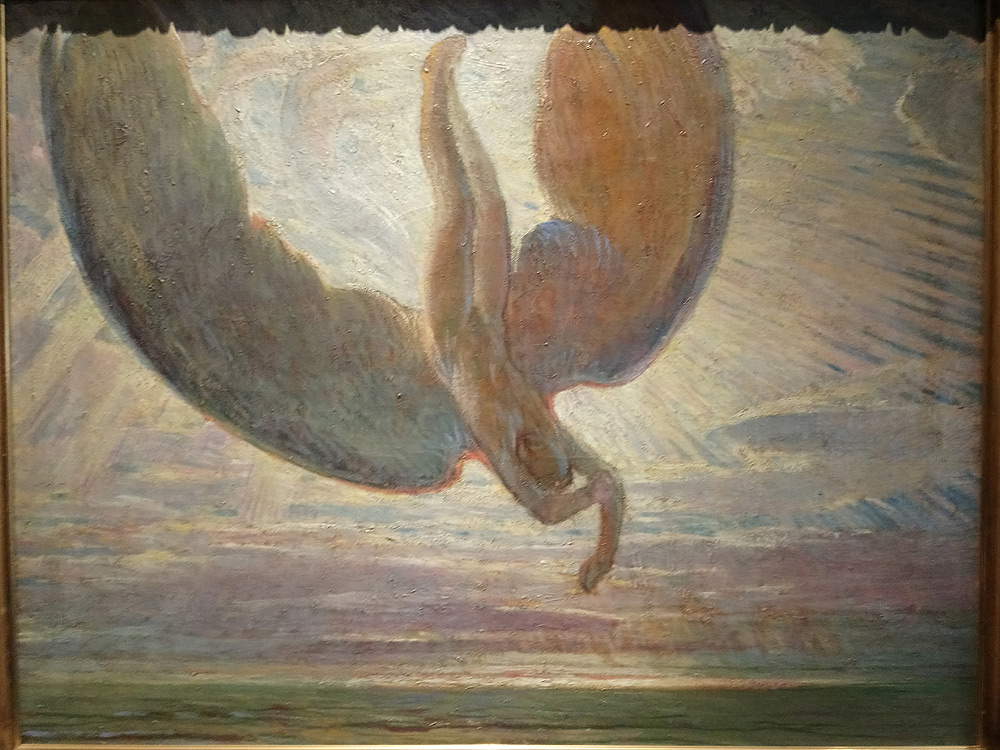

Belonging to the Divisionist phase, this time, however, under the influence of Gaetano Previati (Ferrara, 1852 - Lavagna, 1920), another exponent of the Italian Divisionism current, is the painting The Yoke: a very striking and evocative work characterized by an orange light that spreads throughout the composition. In the distance a farmer is plowing the fields with the help of two oxen, in the foreground, that wearily carry the yoke on their backs; parallel in the sky is the allegory of the Passion with evanescent and ill-defined figures that blend into the blinding light coming from the upper right corner of the canvas. The weight of the yoke is thus placed in relation to the suffering of the Christian Passion. The work was created in 1907 when the artist was commissioned to set up, together with Plinio Nomellini (Livorno, 1866 - Florence, 1943), the International Hall of Symbolism at the 7th Venice Biennale, better known as the Hall of Dream: set up like anearly Christian basilica hall with panels repeating the motif of children with garlands and ribbons and a triumphal procession, the room housed works by eighteen international artists, including Franz von Stuck (Tettenweis, 1863 - Munich, 1928) and Previati and Nomellini themselves; along with the Giogo, Chini exhibited the Baptist andIcarus, the latter present in the exhibition in the version believed to be the preparatory study. The figure shown in its fall is representative of the Symbolist current, which intended to bring fantastic, dreamlike suggestions to the canvas through theuse of symbols: a suggestion that is well evoked by this work. As already stated, Galileo Chini also worked simultaneously with ceramics, and the juxtaposition, in the first room of the exhibition, of some ceramics decorated with female faces in profile with the painting La fabbrica (1901) is illustrative in this sense. The latter, from the Wolfsoniana in Genoa, refers to the birth of theArt of Ceramics and the artist’s pride in having contributed to the reaffirmation of decorative art in Italy; the female faces with blond hair adorned with floral compositions were inspired by Pre-Raphaelite models, as well as Botticellian forms. Ornaments that would later flow, with the predominance of floral or phytomorphic elements, into Art Nouveau.

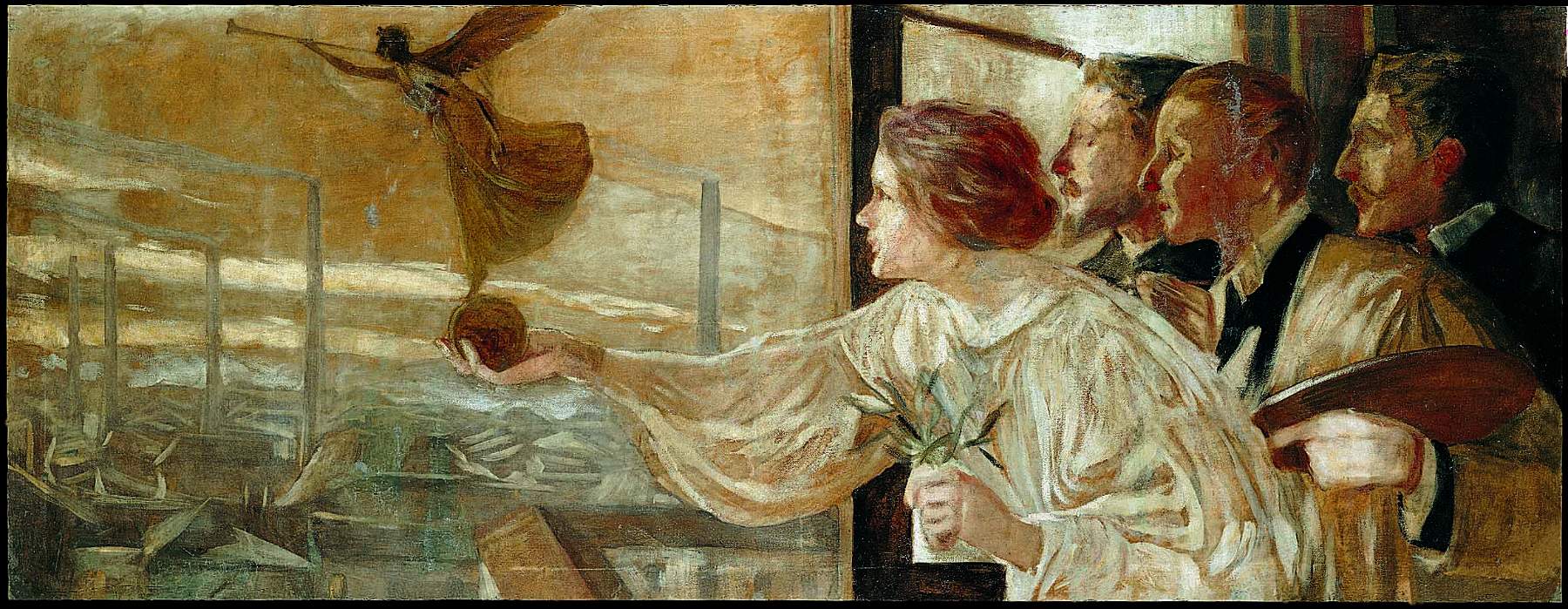

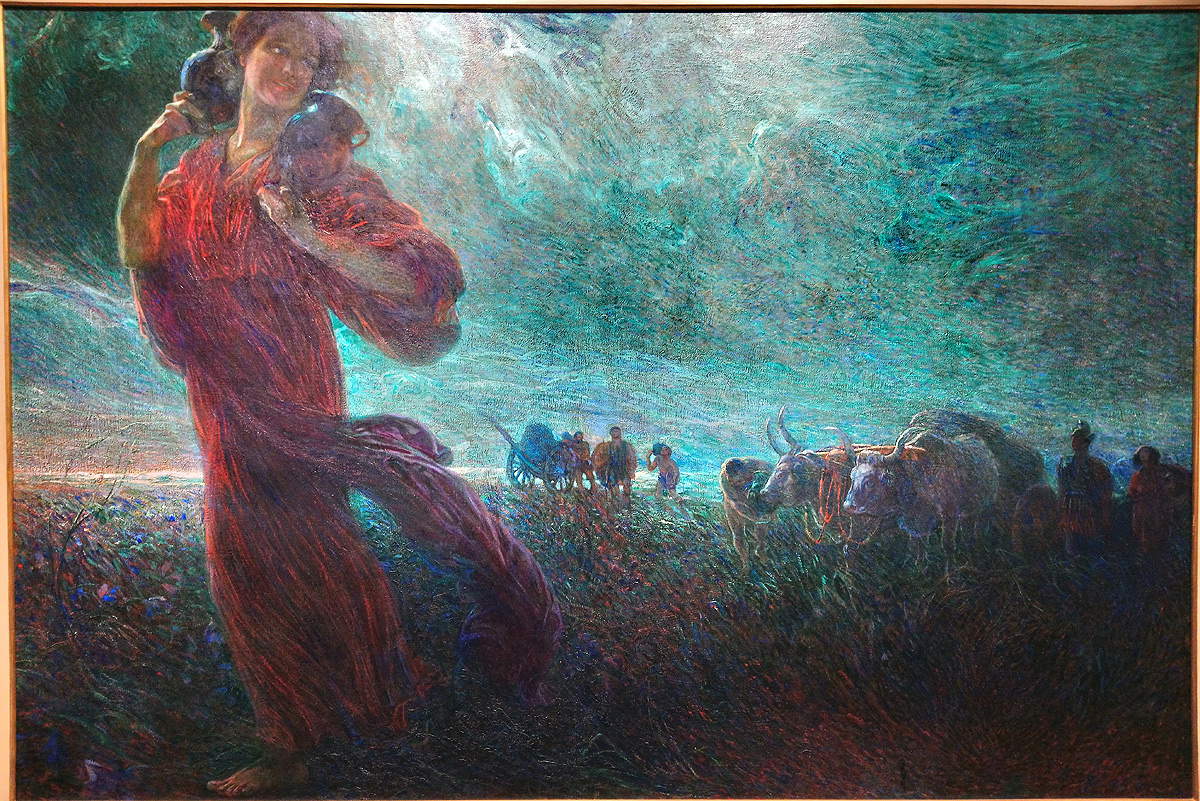

Continuing into the second room, one finds works of Divisionist matrix, starting with the Portrait of Elvira, the wife of Galileo Chini, executed in 1905, where one can also glimpse a Liberty component, but especially in the pair of paintings Voto ai dimenticati del mare and Voto ai dimenticati della terra, reunited here after almost a century since the 1920 Venetian Biennale. These were done after the experience of World War I, and by depicting a snowy scene and the vast expanse of the sea without any presence, the artist intended to pay homage to the fallen of the Great War and to remember this tragic event forever. Fundamental to Chini’s beginnings was the relationship of friendship and esteem he had with the aforementioned Plinio Nomellini, whose masterpiece The Two Amphoras (1910), exhibited at the 9th Venice Biennale, is featured in the exhibition. The female figure in the foreground carrying water-filled amphorae on her shoulders hints at women’s work in the fields, and the amphorae themselves are thematically linked to a particular elongated stoneware vase made in 1916 for the tenth anniversary of the Fornaci Chini in Borgo San Lorenzo, a new factory founded by Galileo and Chino Chini in 1906. It was L’Arte della Ceramica that presented for the first time in Italy manufactures in stoneware, particularly clear salt-surface type with stylized decorations in cobalt blue; even in materials therefore the enterprise designated itself innovative.

|

| Galileo Chini, The Quiet (1901; oil on canvas, 101 x 201 cm; Rò Ferrarese, Cavallini Sgarbi Foundation) |

|

| Galileo Chini, The Yoke (1907; oil on canvas, 124 x 124 cm; Venice, Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna di Ca’ Pesaro) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Icaro (1904-1907; oil on canvas, 90 x 115 cm; Como, Giorgio Taroni Collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, The Factory (1901; oil on canvas, 66 x 172 cm; Genoa, Wolfsoniana) |

|

| Galileo Chini’s ceramics on display in the first room |

|

| Galileo Chini, Il voto ai dimenticati della terra, detail (1916; oil on canvas, 100 x 180 cm; Livorno, 800/900 Artstudio) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Il voto ai dimenticati del mare, detail (1920; oil on canvas, 101 x 182 cm; Rome, Segretariato Generale della Presidenza della Repubblica) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, The Two Amphoras (c. 1910; oil on canvas, 161 x 240 cm; Pisa, Azienda per l’edilizia sociale) |

Having concluded the section on the artist’s initial references to Divisionism, Symbolism and Art Nouveau, the exhibition presents a lengthy exploration of works related to the theme ofwater, both from a landscape and a more strictly faunal point of view. Thus, there is a succession of sea, river or lake scenes executed in a period between 1901 and 1948 in Venice, on the Tyrrhenian coast, in Sicily, on the Arno and at the Fossa dell’Abate: places of Galileo Chini’s life, dear to him because they are located in his lands or because they are connected to happy periods of his working activity. Like the views of the city of Venice, exemplified here in the exhibition by Venice. Chiesa della Salute and Punta della Dogana (1904), a painting that fascinates and immerses the viewer in the pastel colors of blue and pink reflected in the sea and sky. Or L’Arno tranquillo (Morning on the Arno) (1936), a painting characterized by a strong luminosity and clarity, so much so that the river water appears almost transparent. Based on a play of reflections, on the other hand, is the 1932 canvas Riflessi (La Fossa dell’Abate), where the tall trees are reflected in the water and not only that, even the people walking on the bank of the canal are painted upside down in the lower half of the painting. People made with small patches of color are depicted in Spiaggia Tirrena (1948), where the seawater is so shallow that they can only get wet up to their ankles, while the only lagoon landscape in the exhibition is Quiete sul lago Moltrasio (1926), which gives the viewer a real feeling of peace and tranquility. Of totally opposite feelings are the works that recall the bombing and destruction inflicted by the war in the Florentine territory, such as Ponte Santa Trinita (Rovine sull’Arno), executed after the bombing of Florence in 1944.

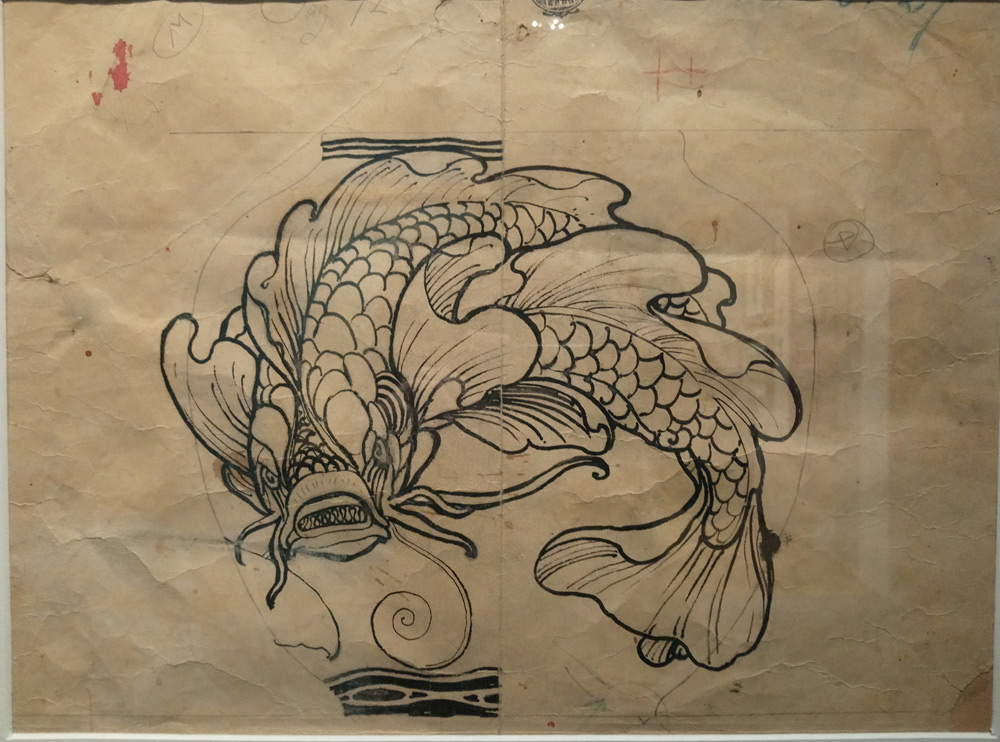

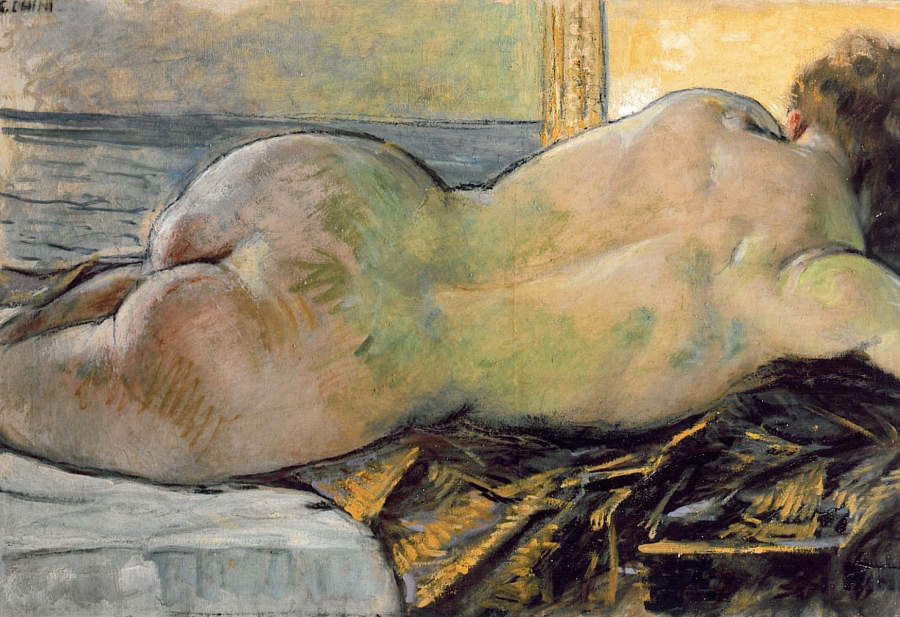

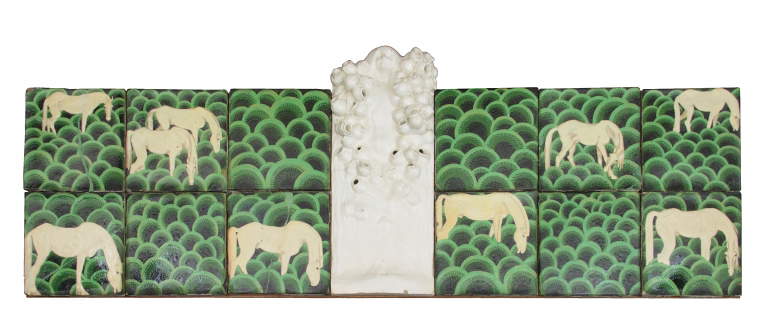

Also leading to the marine theme are a number of portraits: in Nudo disteso (La bionda), a large navy painting hanging on the wall provides a backdrop for a woman lying nude on a bed in the foreground, while it pays homage to theman of the sea in Portrait of His Son Eros (ca. 1950), commander of the motor sailer Orion. Also in this section there is no shortage of ceramics, on which Chini depicted the world of aquatic fauna: fish and shells appear on plates and vases with more elongated or pot-bellied shapes and strong colors. For the decoration of such artifacts, the artist was largely inspired byJapanese art: at theParis Expo he had the opportunity to learn about the phenomenon of Japonism and was so impressed by it that he reproduced on ceramic products the foaming billows in the manner of Hokusai’sWave (Edo, 1760 - 1849) and large freshwater and saltwater fish that twist around the object or seem to threaten the viewer. Accompanying these extraordinary works of craftsmanship is another ceramic masterpiece by Duilio Cambellotti (Rome, 1876 - 1960): the Fontanina dei boccali from the Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche in Faenza; a panel consisting of twelve tiles on which white horses in a pasture are painted and a central tile depicting a nymph with clusters of mugs. And finally, the fine four-panel screen with Waves, damsels of Numidia and a scorpionfish (ca. 1910-1915) refers back to Japanesque scenes, while to the recurring theme of children the two unpublished paintings with babies playing with their little feet in the water surrounded by floral elements, particularly poppies.

|

| Galileo Chini, Venice. Church of the Salute and Punta della Dogana (1904; oil on canvas, 123 x 99 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Spiaggia tirrena (1948; oil on plywood, 43 x 68 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, L’Arno tranquillo (Morning on the Arno) (c. 1936; oil on canvas, 85 x 105 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Quiete sul lago Moltrasio (1926; oil on canvas, 80 x 100 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Ponte Santa Trinita (Rovine sull’Arno) (1944-1945; oil on canvas, 98 x 87 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Sketch for Ovoid Vase with Fish (1906-1911; India ink and pencil on canvas, 38 x 40.5 cm; V. Chini Collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Lying Nude (the Blonde) (ca. 1934; oil on plywood, 65.5 x 91 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Waves, damsels of Numidia and scorpionfish (c. 1910-1915; four-panel screen, oil on panel, 200 x 240 cm; Milan, Galleria Gomiero) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Putto water and flowers (both c. 1910; oil on canvas, 86 x 89 cm; Florence, Private Collection) |

|

| Duilio Cambellotti, Fontanina dei boccali (1910-1914; panel composed of 13 elements in engobed, painted and glazed terracotta, 45.5 x 132 x 9.8 cm; Faenza, Museo Internazionale delle Ceramiche) |

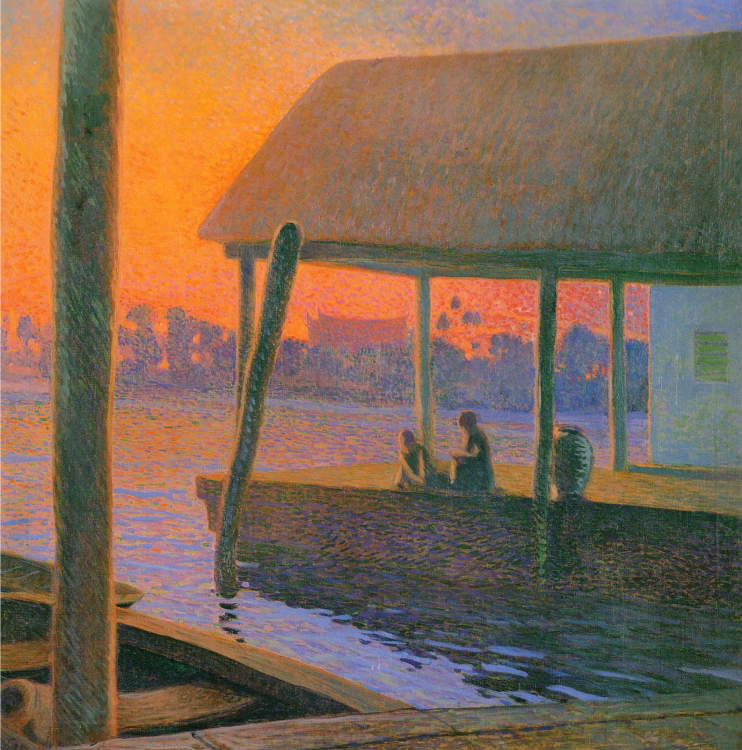

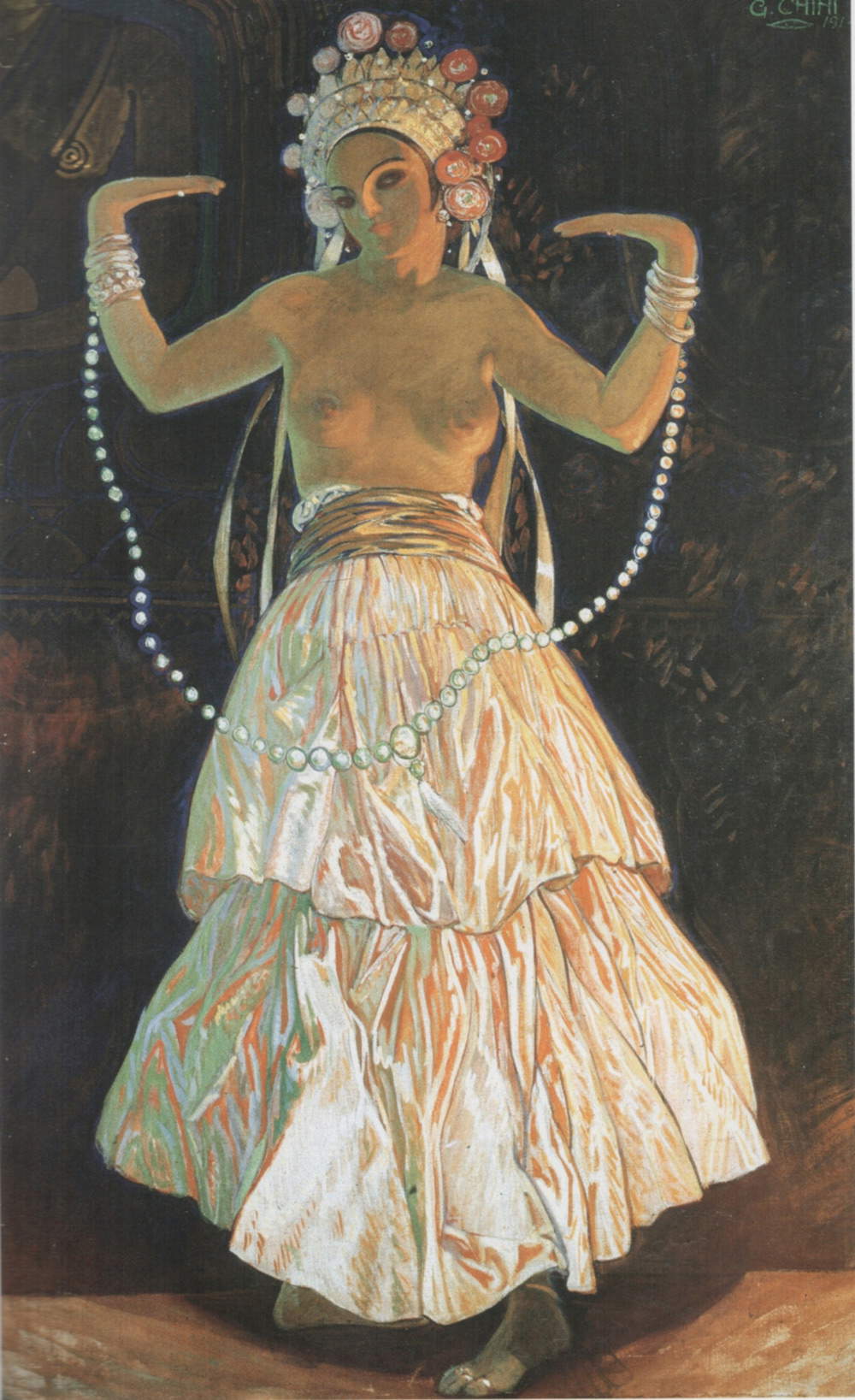

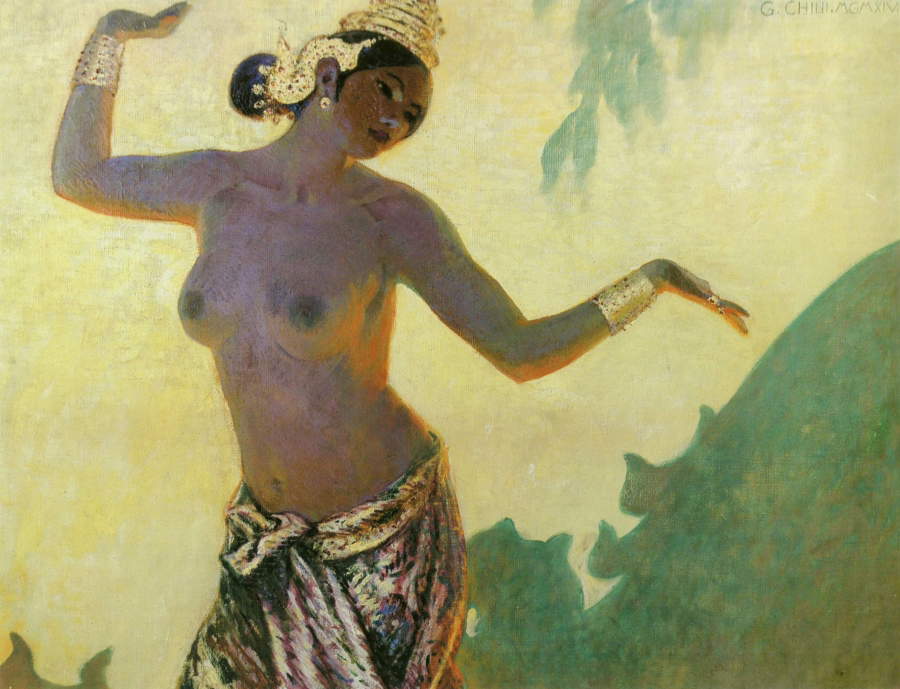

His assignment as the official fitter of the Venice Biennale also earned him the opportunity to travel the routes to Siam: it was at the Venetian event that his works were seen by the Siamese ruler King Chulalongkorn (Rama V), and, according to Chini’s account in his Memoirs, it was the decoration of the eight sails of the dome of the vestibule of the 1909 Biennale that led the Siamese king to commission the Florentine artist to decorate the Throne Palace in Bangkok with frescoes and paintings. Chini departed in August 1911 aboard the steamer Derflinger, arriving at his destination around September 20, on the occasion of Rama VI’s coronation feast. Thanks to that extraordinary voyage, he became one of the leading exponents ofOrientalism in the twentieth century; some of the works on display, such as The Night in the Watt Pha Cheo, The Bisca San-Pen and The Nostalgic Hour on the Me Nam, bear witness to this. The former is set in Thailand’s most important Buddhist temple, the latter inside the Grand Chinese’s gambling den, characterized by dazzling artificial lights; the last work is influenced by Divisionist painting, particularly in the execution of the river water and the sky: the typical colors of the sunset propagate in small strokes throughout the entire painting, sparking great wonder in the viewer. The second section of suggestions from theFar East is devoted to the sensuality of the belly dancers, a dance that also has a strong spiritual component in it: the Moon D ancer and Javanese Dancer, both from 1914, are on display. The Oriental experience came to an end with the creation of the sets for Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot: the premiere of the opera was held on April 25, 1926, at La Scala in Milan, and the set sketches can be admired in the exhibition. The ceramics made during that period also took on oriental-like decorations and predominantly red and blue coloring.

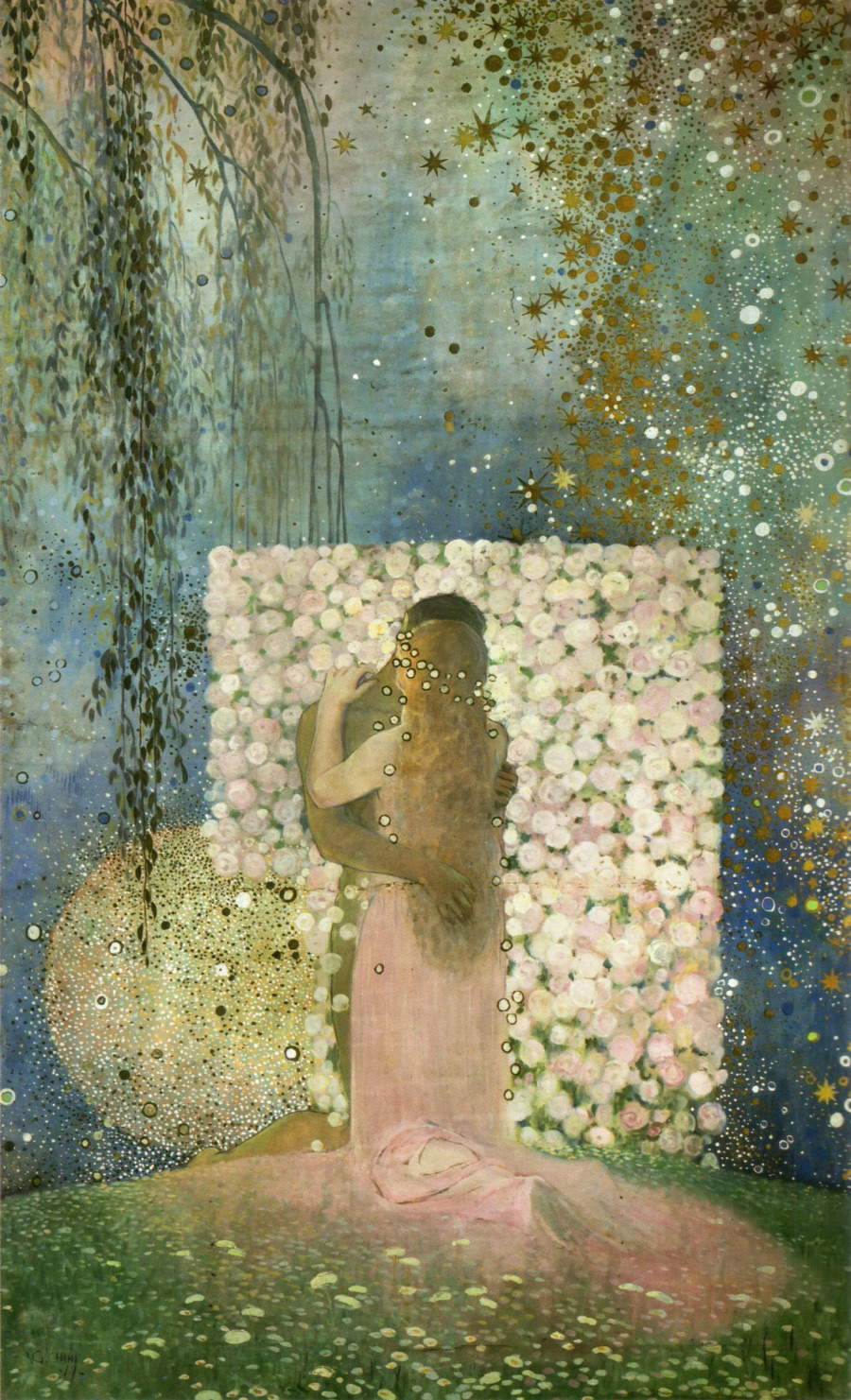

If the layout of the section dedicated to Orientalism led the visitor directly to the lands of the Orient, it happens even more in the last section, the one focusing on the influences of the Viennese Secession, with particular reference to Gustav Klimt. The last two rooms of the Pontedera exhibition sensorially envelop the visitor thanks to the care with which the colors, tapestries, and even the plants were chosen, placed on tall planters with lion heads in turquoise and gold majolica that recall the Terme Berzieri in Salsomaggiore Terme, a place whose decorative layout was entrusted to the artist himself. The two exhibition rooms are also characterized by large paintings hanging on the walls that offer a particular suggestion to the observer: in the first one, two large canvases that were part of the decorative cycle of Villa Scalini completed in 1921 are displayed as wings. These are Life and Love: two paintings, in which pinkish tones predominate, that testify to a fascination with the Klimtian lexicon, nevertheless declined in a personal style. After his extraordinary experience in contact with the peoples of the East, Galileo Chini resumed his role as the official fitter of the Venice Biennale, and in 1914 he was entrusted with the task of setting up the so-called Mestrovic Room, named after the sculptor Ivan Mestrovic (Vrpolje, 1883 - South Bend, 1962), an exponent of the Viennese Secession, whose works were to be brought together in the room entrusted to the Florentine artist. Here Chini prepared eighteen panels linked to each other by the thread of the sacred Spring, embellished with stucco and metalwork. It refers back to this theme, in fact, the large canvas entitled La vita (Life), in which spring is revisited as the rebirth of life, amid floating draperies and trees with pink flowers. The theme of spring is echoed in the polychrome majolica panel Flora, which shows a female figure wearing the typical peplos of ancient Greece and wrapped in brightly colored flowers of small and large sizes. At the same time, the artist intends to represent in the large canvas titled Love the conjugal bond thought of as the union of opposites and as the magical moment of fertilization, the latter highlighted by the presence of a kind of panel formed by pink-colored roses and circular or star-shaped shapes that flood the entire composition. Love is personified by the two figures in the foreground, in the center of the painting, who merge in a gentle embrace; of the man and woman protagonists, their faces are not visible, as the maiden with long blond hair is placed from behind and almost completely covers the male figure. Chini’s Love is a reinterpretation of Klimt’s Kiss.

Between the two aforementioned works, the view opens onto the scenery of the large preparatory study for the painting of Primavera that decorated the salon of the Terme Berzieri in Salsomaggiore Terme: a celebration of the sacred Spring understood as regeneration, rebirth and source of life linked to the benefits of the salso-iodine water. A place devoted tototal harmony that could not have been otherwise decorated than with references to the Taoist conception of yin and yang: in fact, the spa complex designed by Ugo Giusti was entirely clad internally and externally with ceramics and glass designed by Chini from the San Lorenzo Furnaces. Contributing to this totalizing idea of rebirth is a whole series of symbols connected to the plant and animal worlds (hence the name of the last room of the exhibition, Garden of Symbols), including many varieties of flowers, particularly the rose, and then the peacock, beetle, salamander, cockchafer, fish, ram and nocturnal animals; the presence of children and cherubs is also significant and recurrent. Elements that are also found in the ceramic vases, cups and tiles produced first byArte della Ceramica and then by Fornaci San Lorenzo.

|

| Galileo Chini, The Night in the Watt Pha Cheo (1912; oil on plywood, 80 x 65 cm; Milan, Galleria Gomiero) |

|

| Galileo Chini, The Nostalgic Hour on the Me Nam (1912-1913; oil on canvas, 124.4 x 124.4 cm; Tortona, Pinacoteca Il Divisionismo) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Javanese Dancer (1914; tempera on canvas, 200 x 123 cm; Private collection) |

|

| "Galileo Chini, Danzatrice Monn (1914; oil on canvas, 94 x 123 cm; Private collection) |

|

| "Galileo Chini, La vita " (1919; oil on canvas, 277 x 172 cm; Livorno, 800/900 Artstudio) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Love (1919; oil on canvas, 277 x 172 cm; Livorno, 800/900 Artstudio) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Panel “Flora” (ca. 1914; polychrome majolica, 150 x 70 cm; V. Chini Collection) |

|

| Bottom: Galileo Chini, Preparatory Study for the painting of Primavera in the salon of Terme Berzieri (1919; four panels, tempera on paper, 380 x 345 cm; V. Chini Collection) |

Galileo Chini left the management of the Fornaci in 1925 to his nephew Tito, who, together with his brother Augusto, created the decorative installations of the Padiglione delle Feste in Castrocaro Terme. The manufacturing enterprise is still active today under the direction of Augusto Chini’s nephews Mattia and Cosimo. Artists contemporary to Galileo Chini have also been included in the exhibition in order to give the public an understanding of the artistic contacts he had during the various periods of his activity: thus works by, among others, Giorgio Kienerk (Florence, 1869 - Fauglia, 1948), Duilio Cambellotti, Plinio Nomellini, Moses Levy (Tunis, 1885 - Viareggio, 1968), Lorenzo Viani (Viareggio, 1882 - Ostia, 1936), Salvino Tofanari (Florence, 1879 - 1946), and Vittorio Zecchin (Murano, Venice, 1878 - 1947) are featured.

The sought-after exhibition is accompanied by an in-depth catalog with essays written by the curators, scholars and two interesting contributions by direct descendants of the Florentine artist, Vieri Chini (Augusto’s son) and Paola Chini (Vieri’s cousin and Galileo’s direct niece), on the factory and Galileo Chini as artist and man, respectively. The other essays deal extensively with his various artistic influences, from Symbolism to Art Nouveau to Orientalism, and his figure as an interpreter of the changing applied arts between the 19th and 20th centuries. However, it should be pointed out that the catalog lacks fact sheets of the works in the exhibition, a necessary content for the exhaustive study related to an artist. In conclusion, an online repertory of Galileo Chini’s works has been composed, which can be consulted at www.repertoriogalileochini.it, in order to make his multifaceted activity known to an ever wider audience.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.