One of the best-known cases of reuse of anancient image incontemporary art is the celebrated Mimesis, a 1975 work by Giulio Paolini that apparently consists of a simple pair of casts of the Venus de’ Medici placed opposite each other. It was pointed out that the work is simple only in appearance, because in reality the message behind the copies of the Venus de’ Medici is quite complex. We are not in the presence of a quotation that merely pays homage, as is often the case, to the art of the past. Nor, much less, do we find ourselves in front of a Duchamp copycat who presents us with a ready-made that could be a ready-made cast of an ancient statue. Giulio Paolini’s discourse is far more refined: “the intent,” the artist himself had explained in an interview published in 1985 in Tuttolibri, a supplement to La Stampa, “is to capture, leaving it intact, the distance that separates us from those images, but which, at the same time, makes them visible to us.” With his operation, Paolini, in addition to giving substance to the Hegelian assumption that art is ein Vergangenes, that is, something past, makes the observer aware of the ontological impossibility of recreating a certain kind of art, of the conventionality of the schemes we adopt to read art, of the fact that the work of art is such insofar as it is embedded in a network of relationships (with other works, with those who create it, with us who observe it).

Giulio Paolini, in other words, conceptually appropriated a work of art from the past so that our attention would focus not so much on the cast itself (which in itself has little value), but on what gravitates around the cast. An image that knows a new life, a shift in meaning, an image that looks to the past but is actually firmly projected onto the present, due to the fact that the theme of reuse (in its various declinations: citation, revisitation, appropriation... ) often implies, in contemporary art, a more or less conscious insertion within a discussion. This is precisely the topic at the center of an interesting exhibition currently underway at the Centro Arti Plastiche in Carrara, Le immagini reinventate, which is highly topical in that it is part of a recent debate on which many have wished to express their views: the curator Lucilla Meloni, who is so attentive to the theme of citation in contemporary art that she has dedicated one of her latest works to it(Arte guarda arte. Practices of citation in contemporary art, Postmedia Books, 2013), brings to the city of marble a cross-section of this debate, namely the works of fourteen artists who have posed the problem (some more, some less consciously) of how to deal with images from the past. “Art has always been a looking and a looking at itself,” Lucilla Meloni wrote in the aforementioned book, and quoting Didi-Huberman pointed out that “the work of art is an image that is always anachronistic because it contains within it various and mixed differentials of time,” that “in the work of art different times and different forms go together,” and that “the very condition of reading the work sinks into temporal displacement.”

If one opts to follow Didi-Huberman from his starting point, that is, the observations of Aby Warburg and his concept of Nachleben (“Survival”), thanks to which the idea of a linear and evolutionary development of art history was subverted (a model that for the French philosopher is embodied by art historians such as Vasari and Winckelmann), one will necessarily come to face the problem of how to reread images in light of the fact that images themselves assimilate “spectral memories.” For Didi-Huberman, therefore, it is necessary to acceptanachronism, that is, the simultaneous presence of two epochs, as a model for those who study the history of images: this is because images are “an extraordinary set of heterogeneous times,” and consequently art history needs to configure itself as a discipline founded on a temporality that takes into account the fact that past, present and future are not three detached entities, but coexist united by strong bonds.

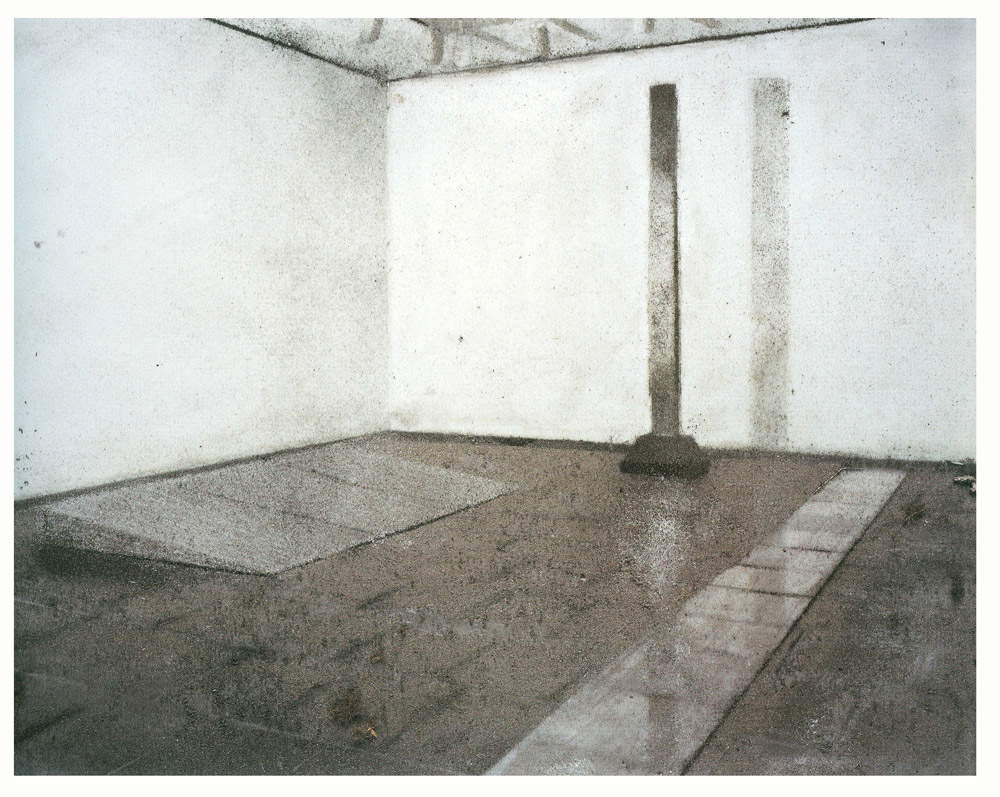

|

| Images reinvented: a room of the exhibition. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

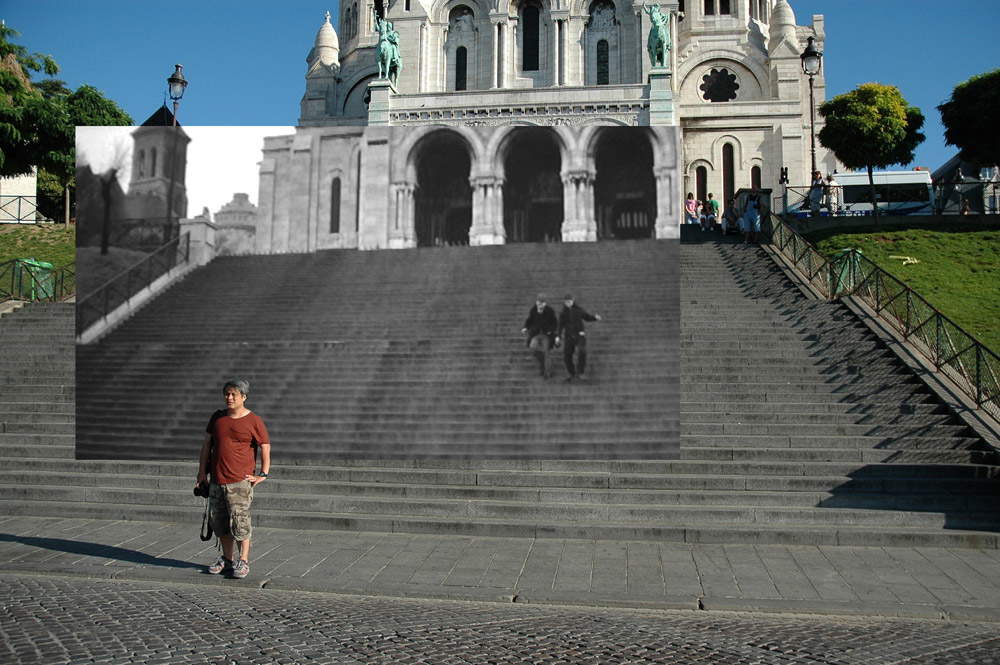

To make this vision of art and art history clearer, the Carrara exhibition cleverly opens with a significant work such as Ver Verifica incerta by Gianfranco Baruchello (Livorno, Italy, 1924) and Alberto Grifi (Rome, Italy, 1938 2007). A montage of discarded materials from American films of the 1950s and 1960s that presented itself to the audience with various levels of reading and that went beyond the logical consequences of the meaning of the films of which it was composed, broke the linearity of their plots, made evident the assumption that the history of art (and, in this case, of cinema) is not continuous narration, showed how certain patterns, certain situations, certain modes survived at a distance of time, and in different contexts: interesting, moreover, to note that Didi-Huberman himself, in his Devant le temps, had used precisely the term montage to indicate that “set of heterogeneous times” of which images are composed. Cinema has, after all, been a sphere of experimentation for much contemporary art, also by virtue of the fact that, asserted videoartist Douglas Gordon in an interview with Flash Art, films “are icons in common use,” and they become so much so that, quoting Lucilla Meloni again, artists “freeze them in photography,” as happens in Still Here by Gea Casolaro (Rome, 1965), another work in the exhibition that is particularly iconic in taking on the problem of the simultaneity of times.

The Roman artist froze some scenes from films shot in Paris, traveled to the French capital to look for the places in which the scenes were set, took photographs depicting them, adopting a point of view identical (or almost identical) to that of the camera, and then inserted the film frame into the image captured on site. This operation “on the one hand cancels,” the curator explains, “and on the other enhances the difference in time and place identity and enacts a fictitious coexistence between past and present, between reality and fiction, between places of life and film sets.” Gea Casolaro’s is also a work that lends itself to readings of different kinds, because there is not only that reflection on a time in which present and past cohabit, but there is also the desire to connect to a discourse on memory, which is also of a multiple nature, because it is both collective (that of films as icons of common use) and personal, intimate, sentimental (where by “personal” memory one can safely intend also the memory of the individual stories that in the places investigated by Gea Casolaro took place).

|

| Gianfranco Baruchello and Alberto Grifi, Verifica incerta (Disperse Exclamatory Phase) (1964-1965; 16 mm film from 35 cinemascope film, color, duration 35’; Rome, Courtesy Archivio Gianfranco Baruchello) |

|

| Gea Casolari, some images from the Still Here cycle. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Gea Casolari, Still Here_L’air de Paris - Quai d’Orléans (2009-2013; inkjet print on aluminum, single print run, 64 x 100 x 2 cm; Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart) |

|

| Gea Casolari, Still Here_Le quatre cents coupes - Escalier du Sacre Coeur (2009-2013; inkjet print on aluminum, single print run, 46.5 x 70 x 2 cm; Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart) |

|

| Gea Casolari, Still Here_Seul two - Rue Pierre Semard (2009-2013; inkjet print on aluminum, single run, 46.5 x 140 x 2 cm, diptych; Courtesy the artist and The Gallery Apart). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

The theme of memory is, moreover, one of the main themes of The Reinvented Images, and it explodes in all its power in the second room, where we find the fragment Untitled by Cyprien Gaillard (Paris, 1980), which is part of CAP’s permanent collection: it is not in itself a work of art, since it is simply a fragment of the marble atrium of the World Trade Center in New York, recovered after the September 11, 2001 attack. The work lies, if anything, in the ability to reinvent that fragment as a witness capable of becoming the bearer of a memory that is also, again, intimate and collective (so intimate that, when Untitled was presented for the first time at the 2010 Carrara Sculpture Biennial, it was placed in a sort of basin sunk in the grass of a garden), but also in its becoming a symbol of a degradation triggered by time that determines the succession of historical and cultural transformations: central, in Cyprien Gaillard’s production, is the research on ruins, on the decay of societies, which the artist carries out almost with a clinical eye, simply presenting to the observer the remains of a more or less near past.

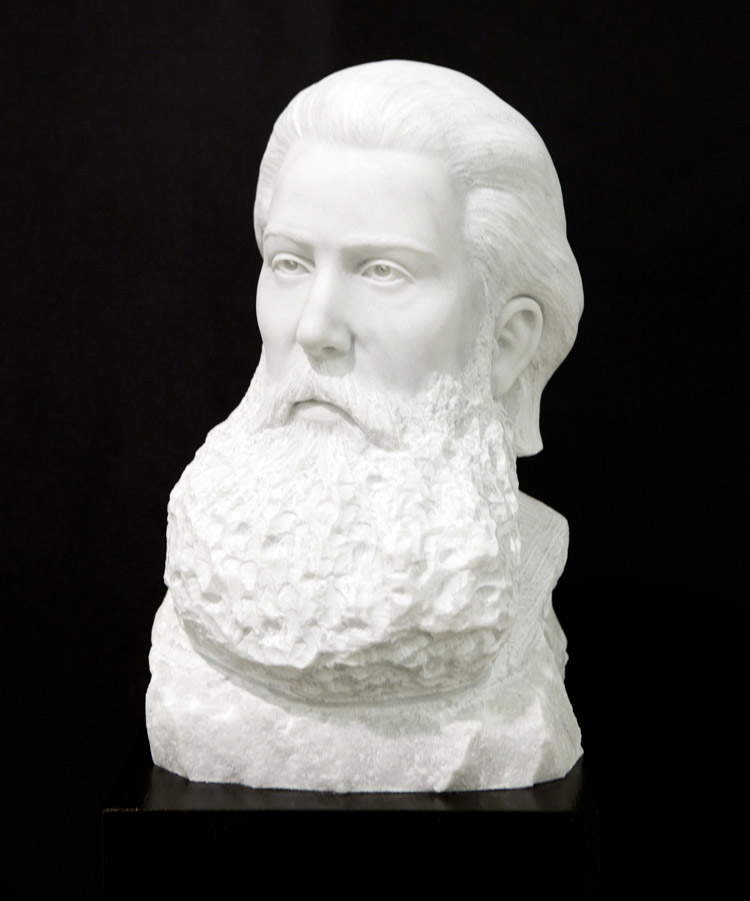

Another artist who has long centered his research on memory is American Sam Durant (Seattle, 1961), whose works made for the 2011 project Propaganda of the deed (“Propaganda of the fact”) are shown again in the exhibition: are portrait busts of six anarchists (in order of how they are exhibited at CAP: Francesco Saverio Merlino, Marie-Louise Berneri, Errico Malatesta, Carlo Cafiero, Renzo Novatore, Gino Lucetti) that stand out against the large black flags that give the work its title(Black Flag, Unfinished Marble). The artist, who has always been socially engaged, returns to a traditional type of figuration to pay homage to the city of Carrara, the historic international capital ofanarchism, and some of the protagonists in the history of the anarchist movement, a fundamental component of Carrara’s memory. In Durant’s work, the citation (in this case, portraits of anarchists inferred from photographs) apparently takes on the contours of homage that does not question the ontological precedence of the original: in fact, a deeper reading reveals a dense and refined conceptual work behind the appearance. The busts, meanwhile, are six in number, and they are separate but part of a single installation: it seems almost a reference to the collective dimension of the anarchist movement that feeds on the fundamental experiences of individuals. And then, fundamental is the unfinishedness that characterizes all six portraits. When Delacroix entrusted his Journal with the judgment of Michelangelo’s unfinished, he wrote that this process gives meaning and value to the completed parts. The same could be said of Sam Durant. His unfinished is the “gateway” that “places them in a narrow dimension between presence and absence,” and in which “the data of history and the biographies of the characters are re-actualized,” it is the intangible ground within which that memory whose memory the work seeks to take on finds its place: the impossibility of establishing precise and stable boundaries to define anarchism, the incompleteness of an ideal that history has seen find concreteness only in the Spain of ’36 (and for a few months), the struggles of those who have fought, are fighting and will fight for a more just society.

|

| Cyprien Gaillard, Untitled (New York Marble Sculpture) (2010; white marble fragment, 3 x 15 x 15 cm; Carrara, Centro Arti Plastiche) |

|

| Sam Durant, some portraits from the Black Flag series , Unfinished Marble (2011; Carrara marble; Courtesy Franco Soffiantino Contemporary Art Productions). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Sam Durant, Black Flag, Unfinished Marble ( Carlo Cafiero) (2011; Carrara marble, 45 x 29 x 28 cm; Courtesy Franco Soffiantino Contemporary Art Productions) |

|

| Sam Durant, Black Flag, Unfinished Marble (Marie-Louise Berneri) (2011; Carrara marble, 45 x 28 x 23 cm; Courtesy Franco Soffiantino Contemporary Art Productions) |

|

| Sam Durant, Black Flag, Unfinished Marble (Gino Lucetti) (2011; Carrara marble, 45 x 28 x 20 cm; Courtesy Franco Soffiantino Contemporary Art Productions). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

Instead, art history enters The Reinvented Images with Mauricio Lupini ’s Diorama penetrable (Caracas, 1963), a clear reference to the Penetrables by one of the leading exponents of kinetic art, Jesús Rafael Soto, inventor of these bizarre architectures capable of altering the viewer’s point of view by acting as a screen that fragments what lies beyond the structure, but also to involve him directly as an open work into which the public can enter (hence the name) to see reality altered by the lamellae that make up the work, with all that conceptually may follow (just think of the work’s ability to cancel the distance between art and reality: a topic that is still of urgent relevance). Lupini, with his work, intends to historicize the work of his compatriot Soto, and he intends to do so on a conceptual level, because in its physical and structural characteristics the work is perfectly identical to Soto’s, were it not for the fact that, in Lupini, the lamellae are created from sheets of newspapers and magazines selected with care and precise purposes, and that to the adjective “penetrable” is added the noun “diorama,” which indicates the display cases with which, in science museums, natural environments are reconstructed. Lupini, in essence, poses almost more as a historian than an artist, and wants to offer the visitor a “diorama” in which to observe the “reconstruction” of Soto’s work: thus, one can also understand the reason why the author made extensive use of pages from science journals.

In the sphere of art history also moves the work of Brazilian Vik Muniz (São Paulo, 1961): it is a photograph from the series Pictures of dust, which Muniz made in 2000 by creating images literally made of dust collected from used vacuum cleaner bags, and which reproduced a series of minimalist works by artists such as Donald Judd, Robert Morris and Richard Serra, preserved at the Whitney Museum in New York, for which the series was moreover intended. The title of the Whitney’s exhibition, The Things Themselves, echoed a remark by Edward Weston, who wrote in 1924 that “the camera should be used to record life, to render the substance and quintessence of things themselves, whether they be polished steel or throbbing flesh.” Faced with Muniz’s photography, one might wonder what “the thing itself” might be. The artworks of the minimalists? The dust? Or the photograph itself, since the end result of Muniz’s operation arises from a further step, namely theenlargement of the photograph taken to the image made from dust? It follows that Muniz’s reading is anything but ironic, on the contrary: it is a reflection, also quite complex and inserted within a long historical tradition, on the complexity of vision and perception, on the necessary infidelity of photography, but also on the very course of art, with the solidity of minimalist masses that, reproduced in powder, take on smoky and elusive contours (obtained, moreover, with an elusive element par excellance), as if to convey the idea that there are no styles destined to endure and that all movement is transitory.

Finally, the work by Debora Hirsch (St. Paul, 1967), entitled donotclickthru (Santo Expedito), an oil on canvas composed of a series of images of St. Expedito of Melitene, depicted in the classic solemn pose, holding the cross with the inscription “Hodie” (“Today”) and crushing the crow holding the scroll with the inscription “Cras” (“Tomorrow”), deserves a mention. Witnesses of an ante litteram “social” virality, Debora Hirsch’s holy cards give evidence of how our appetite for images and, above all, for sharing them, transcends the ages: if before they were the holy cards to be distributed when the faithful received a grace from Saint Expedite, now they are the memes circulating on Facebook.

|

| Mauricio Lupini, Diorama Penetrable (Domus 1954-1961) (2014; magazine pages cut out and pasted; Courtesy the artist). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Mauricio Lupini, Diorama Penetrable (Domus 1954-1961) (2014; cut-and-paste magazine pages; Courtesy the artist). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Vik Muniz, Pictures of dust, 2000. Donald Judd, Untitled, 1965, Barnett Newman, Here III, 1965-66, and Carl Andre, Twenty-Ninth Copper Cardinal, 1975, installed at the Whitney Museum in “Sculpture from permanent collection,” July 14 - September 5, 1982 (2000; bleach bath print, 132 x 163 cm; Rome, Private Collection) |

|

| Debora Hirsch, donotclickthru (Santo Expedito) (2015-2016; oil on canvas, 102 x 140 cm; Milan, PACK Gallery) |

The Reinvented Images is a timely and strong, refined and sophisticated exhibition, organized and illustrated also with a certain clarity, which tries to answer a question that the curator has been asking for years, namely how the practice of reuse, in all its meanings (and the exhibition is not lacking in examples applicable to every situation), is placed in the context ofcontemporary art, leaving open a series of reflections about the loss of the principle of authorship, dislocations of meaning, the reinterpretation of media (and their transition from tool to language), the value of memory, and the timing of art history. An exhibition that is entirely consistent with Lucilla Meloni’s studies and that seems to give substance to her 2013 book, towards which the catalog of Le immagini reinventate (Edizioni ETS) at the same time summarizes and extends the content. An exhibition, it would be added, of a great city, set up in a museum that has enormous potential: the Plastic Arts Center is a growing museum, endowed with an important permanent collection and housed in a space, that of the former convent of San Francesco, which is functional, coherent and reorganized according to modern criteria. It is hoped that this important exhibition can make people understand how important it is to reflect on the CAP (starting with some fundamental nodes, such as that of scientific direction and that of promotion) and to invest in a museum that is truly equipped with every requirement to stably maintain the role of protagonist of contemporary art in Italy.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.