by Ilaria Baratta, published on 30/04/2019

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Artistic Life at the Time of Napoleon" in Milan, Palazzo Reale, March 12 to June 23, 2019.

It comes with an innovative thrust, right from its first room, the exhibition dedicated to Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (Montauban, 1780 - Paris, 1867), set up in Milan, at the Palazzo Reale, and open until June 23, 2019. The exhibition’s intention, as stated in its catalog and in the first explanatory panel of the exhibition itinerary, is "to render to the painting and sculpture of the years 1780 - 1820 its innovative force, and wanting to dare its precursor Romanticism" and to present for the first time to the Italian public the artistic production of Ingres, an artist among the major exponents of Neoclassical painting, “definitively overcoming a current and pejorative vision of Neoclassicism.” Considered a period characterized by a banal and cold return to antiquity, in which the formal purity of sculptural masterpieces andcivic or private heroism in particular in paintings are exalted, it was Mario Praz with the publication of his Gusto neoclassico, in 1940, who laid the foundations for a rehabilitation of the propagations of that movement, which until then had been the object of discredit. A new vision pursued during the 1960s by the early texts of Hugh Honour and Robert Rosenblum and by two significant exhibitions held in 1972 and 1974, in London, Paris and New York, entitled The Age of Neoclassicism and De David à Delacroix. In an interesting contribution of the Milan exhibition catalog, which consists of an in-depth interview by Stéphane Guégan, curator of the exhibition, with Philippe Bordes, one of the leading scholars of Jacques-Louis David (Paris, 1748-Brussels, 1825), neoclassicist and Ingres’s master, it is asserted that “Praz rejected always any rationalistic and puritanical reduction of the movement, of which, on the contrary, he observed different facets and sensibilities,” recalling how there was a widespread view that the Neoclassicism movement, with David and his contemporaries, had generated “the worst academicism, a cold, pedantic painting, separated from life and creativity, stifled by a virtuous mania for the antique.” In reality, this return to antiquity is delineated not as a mere imitation, but as a renewing shock, rejecting Rococo painting considered untrue and taking as its absolute protagonist the figure of Napoleon Bonaparte as the new Augustus or Caesar. Indeed, it speaks of the “paradoxical modernity of neoclassicism,” as the teachings of the past are linked to a contemporary aesthetic consisting of modern wars and democratic portraiture. In this sense, the exhibition Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Artistic Life in the Time of Napoleon aims to highlight for the first time in Italy the “double inspiration of a critical era,” that between 1780 and 1820: an era marked by Napoleon’s great power, in which the city of Milan becomes one of the most active capitals ofFrenchified Europe, and by the juxtaposition-mesquilibrium between theexaltation of virility and dark, melancholic impulses.

The passion for antiquity thus developed into a new approach to human nature, to body and soul, exemplified in the predominance of the male nude, a symbol of virility and rebirth of the times and positive action, and in theexploration of the psyche and eros.

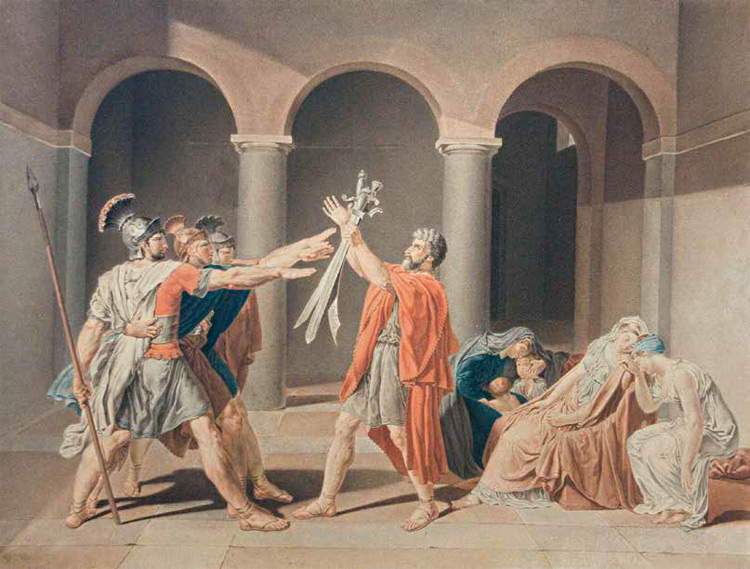

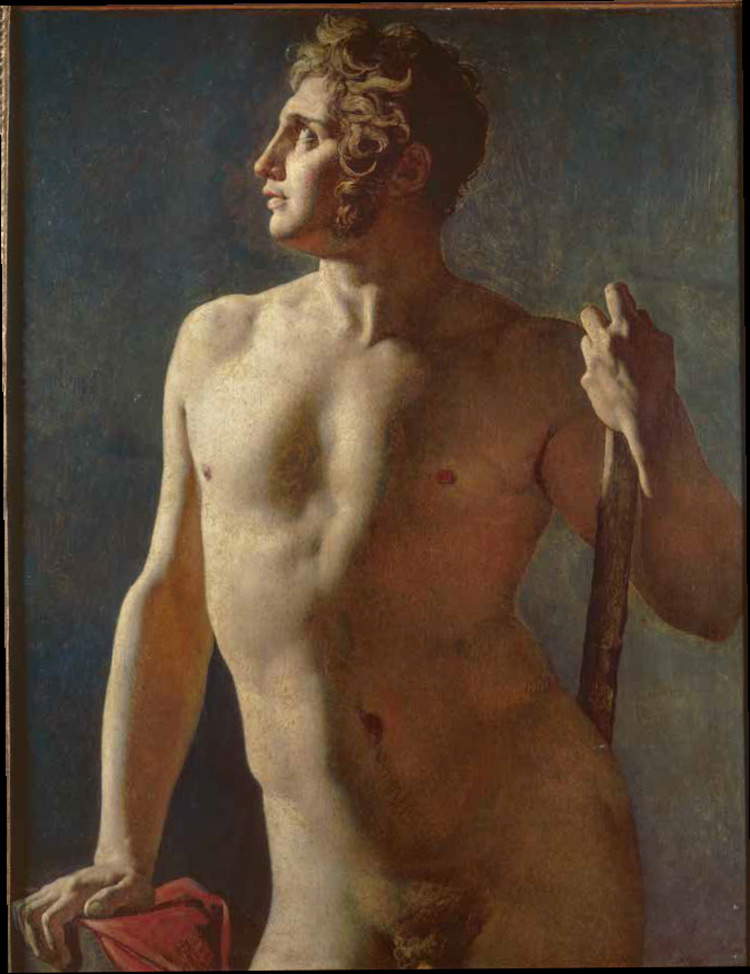

The two trends, which converge in David’s masterpiece that became a canvas-manifesto of Neoclassicism, the Oath of the Horatii, from 1785 (the anonymous and unpublished watercolor from Ingres’ documentary collection, now housed in Montauban, is on display here), are well told in the first two sections of the Milan exhibition: the first includes the Male Nude known as David’s Patroclus, a heroic nude made in 1780 in which the plasticity of the tense muscles and the wind-whipped hair are noticeable, and the Male Torso depicted by Ingres, thanks to which he was awarded the Prix du torse in 1801, an award that, in addition to offering the winner a sum of money, allowed access to the Prix de Rome examinations, a prize that the artist would obtain shortly thereafter in the same year. Instead, the second includes works that evoke melancholy andoneiricism, such as the Melancholy of Constance Charpentier (Paris, 1767 - 1849), a student of David’s, which recalls the group of women in the Oath of the Horatii and casts the snow-white body of an unhappy girl in a typical melancholy landscape formed by a weeping willow, a stream and a grove; Endymion’s Sleep, made in 1791 by another student of David’s, Anne-Louis Girodet (Montargis, 1767 - Paris, 1824): the shepherd Endymion, eternally condemned to deep sleep for courting Juno, is observed in amorous ecstasy at nightfall by Diana, a goddess in love with the perfection of his appearance. And Ingres’ famous monumental masterpiece, The Dream of Ossian, commissioned from him in 1811 for the ceiling of Napoleon’s bedroom at the Quirinal Palace: the painting is inspired by the Songs of Ossian by the Scottish poet James Macpherson (Ruthven, 1736 - Belville, 1796) and depicts in a night scene the poet Ossian surrounded by his most terrible dreams, such as heroes who have died in battle and their children appearing to him, while the dog observes the host of the dead and is about to bark. The work is therefore built on the co-presence of the living and the dead, of dream and reality. Both the theme of melancholy and the theme of dreaming presented by these later masterpieces by students of Jacques-Louis David are to be seen as anticipating the later Romantic movement.

|

| Anonymous, The Oath of the Horatii, by Jacques-Louis David (s.d.; watercolor, 40.8 x 53.7 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jacques-Louis David, Male Nude called Patroclus (1780; oil on canvas, 121.5 x 170.5 cm; Cherbourg-en-Cotentin, Musée Thomas Henry) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Male Torso (1801; oil on canvas, 102 x 80 cm; Paris, Beaux-Arts de Paris) |

|

| Constance-Marie Charpentier, Melancholy (1801; oil on canvas, 130 x 165 cm; Amiens, Musée de Picardie) |

|

| Anne-Louis Girodet, The Sleep of Endymion (1791; oil on canvas, 90 x 117.5 cm; Montargis, Musée Girodet) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Dream of Ossian (1813; oil on canvas, 348 x 275 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

However, the great protagonist of this era was Napoleon Bonaparte (Ajaccio, 1769 - St. Helena Island, 1821), who was portrayed by the most celebrated artists of the time, starting with David: in fact, his is the painting Napoleon Crosses the Great St. Bernard Pass of 1803, depicted wearing a broad billowing cloak while riding a rampant white horse; an image that hints at the great leader’s pride.

As a testament to the sheer volume of Napoleon’s portraits, the Milan exhibition shows a roundup of them, as well as various episodes from the general’s successful campaign in Italy. After a timely military campaign that began on April 12, 1796 by crossing the Cadibona Pass, the French army led by the young Napoleon entered Milan on May 15 of the same year, after conquering Liguria and Piedmont. And it was precisely the Lombard city that became the capital of the arts, experiencing a moment of great prosperity: significant renovations of monuments and green spaces were carried out, and many Italian artists participated in all this, increasingly increasing the cultural wave underway. It would also be in Milan, in the Duomo, that Napoleon would be crowned King of Italy on May 26, 1805, initiating many cultural and social transformations with the aim of "Frenchifying Italy" and bringing it into dialogue with the most modern European trends. Among the works celebrating Bonaparte and his campaigns on display are the pencil drawing executed by Andrea Appiani (Milan, 1754 - 1817) in 1801 and kept at theBrera Academy, which depicts Napoleon with his face turned to the observer’s right and his hair framing his face (Appiani had already portrayed him in 1796, when the day after he entered the city of Milan, General Hyacinthe-François-Joseph Despinoy had ordered the artist to paint a portrait of the leader, and from this painting other specimens were taken that spread Napoleon’s physiognomy throughout Italy and France); and also General Bonaparte Crosses the Alps and Attack on the Fort of Bard by Nicolas-Antoine Taunay (Paris, 1755 - 1830) and Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidault (Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846). Major masterpieces featured are the colossal Bust of Napoleon made by Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 - Venice, 1822) and the extraordinary Fasti di Napoleone, the complete series of thirty-five engravings in which the most significant battles and episodes of the first Italian campaign are depicted: original cycle painted on canvas for the Sala delle Cariatidi in the Royal Palace was destroyed by bombing during World War II, but the engravings executed with theetching techniqueretouched with burin were made under Appiani’s supervision by Giuseppe Longhi, a professor at the engraving school of the Brera Academy, and his pupils Francesco and Giuseppe Rosaspina, Michele Bisi and Giuseppe Benaglia, between 1807 and 1816.

Another extraordinary testimony of that era, of unique refinement, are the fifteen miniatures reproducing the Sommariva collection by Adèle Chavassieu d’Haudebert (c. 1788 - 1832) in enamel on copper: these depict characters from mythology, allegories and historical figures, including also Napoleon as Hercules the Peacemaker (Allegory of the Cisalpine Republic). A native of Lodi, Giovanni Battista Sommariva (Sant’Angelo Lodigiano, 1762 - Milan, 1826) was in Milan shortly before Napoleon’s triumphal entry and managed to introduce himself into the city’s political sphere, becoming a prominent figure; in the meantime he began to collect works by great artists of his contemporaries and even after the end of the Empire he patronized the latter, from David to Pierre Paul Prud’hon (Cluny, 1758 - Paris, 1823), from Canova to Appiani. Prud’hon’s is the portrait of the collector in the exhibition dated 1814 and housed at the Pinacoteca di Brera, in which Sommariva is placed between the Canova statues of Palamedes and Terpsichore, intending to emphasize his role as a major Italian patron and his friendship with the famous sculptor.

|

| Andrea Appiani, Portrait of Napoleon (1801; black pencil and white chalk on brown paper, 13 x 11 cm; Milan, Brera Academy of Fine Arts) |

|

| Nicolas-Antoine Taunay and Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld, General Bonaparte Crosses the Alps and Attack on the Fortress of Bard (both 1801; oil on canvas, 183 x 120 cm; Milan, Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per la Città Metropolitana di Milano, on deposit at the Museo del Risorgimento) |

|

| Antonio Canova, Colossal Bust of Napoleon (1804-1809; marble, 88 x 52 x 42 cm; Milan, Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio per la Città Metropolitana di Milano, on deposit at Palazzo Cusani) |

With his monumental painting Napoleon I on the imperial throne, Ingres differentiated himself from all other artists who had portrayed Napoleon until then: he depicted him seated on the throne resembling a Jupiter or a Roman or Byzantine emperor; his appearance was comparable to a superhuman, divine power, but with concrete attributes such as the red velvet and ermine robe, the head girded with gold, the scepter with the hand of justice, the ivory spheres of the throne, the back of the throne forming a kind of halo, and the eagle opening its wings in the weave of the carpet. A powerful figure intended to synthesize and renew previous dynasties. However, the large painting did not please and sparked criticism and indignation: Champany even refrained from presenting it to the emperor because it was “too little resemblance and its execution is not sufficiently perfected.” It was then purchased by the Legislative Corps to decorate the salon of the Bourbon Palace and presented at the Salon of 1806. Even, with a play on words, the “unhealthy portrait of His Majesty,” the "mal ingres" of the emperor’s complexion (the homophone malingre means “shabby”) was emphasized. Kept at the Louvre since 1815, the work began to be reevaluated from 1832, when it was moved to the Hôteldes Invalides, although it was little noticed. In the exhibition hall of the Palais Royal, Napoleon I on the imperial throne stands out illuminated, giving visitors a feeling of power and dominance; the monumental canvas is accompanied by some preparatory drawings kept in the Musée Ingres in Montauban, which focus in particular on the coronation robe and the hand of justice.

Beginning in the next section is a survey of Ingres’s artistic production, from his training to his favored themes and subjects, which testifies to the artist’s manifest Italian-ness and his dominant role in art before, during, and after the Empire.

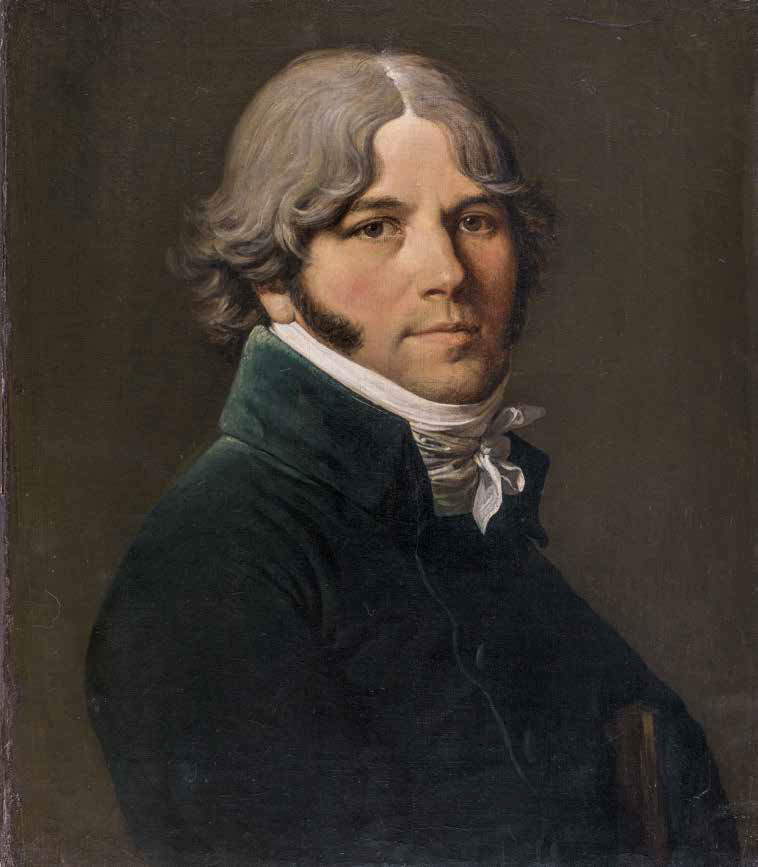

The young artist from Montauban, whose appearance must have been very similar to theSelf-portrait made by Julie Forestier in 1807, on display here (this is one of the first copies on a model of the self-portrait made by the artist kept in Chantilly by Ingres’s fiancée, also a painter), owes the beginning of his training to his father, Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres, an artist himself. It was he who saw the great talent of his son, still a young boy, and who made him leave his hometown to attend theAcadémie Royale of painting, sculpture and architecture in Toulouse. The son’s gratitude is embodied in the portrait that the artist made of his father in 1804, on the occasion of the latter’s visit to Paris and the year of Napoleon’s consecration: for this portrait Ingres drew inspiration from the Flemish tradition, highlighting theman’s elegance and refinement and not letting the real vision he had of him as a husband and father show through. He was in fact an unfaithful husband who abandoned Ingres’ wife and little sisters without financial help. However, he left no trace of this unhappy appearance in the portrait in question; on the contrary, he depicted him as pleasant and younger than in reality.

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Napoleon I on the Imperial Throne (1806; oil on canvas, 263 x 163 cm; Paris, Hôtel national des Invalides, Musée de l’Armée) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Objects for the Coronation (s.d.; graphite on paper, 12.1 x 8.8 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Julie Forestier, Self-Portrait of Ingres, from Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1807; oil on canvas, 65 x 53 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Jean-Marie-Joseph Ingres (1804; oil on canvas, 55 x 47 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

As already stated, in the following years it would be David who would be responsible for the training of the talented artist, welcoming him into his Paris studio and having him reproduce some of his most famous masterpieces, such as the Oath of Horatii , as an exercise (the unpublished watercolor from the Ingres collection preserved in Montauban is on display in the exhibition). In David’s studio, Ingres met the Italian sculptor Lorenzo Bartolini (Savignano, 1777 - Florence, 1850), whom he portrayed in a 1805 painting, in which the influence of Italian Renaissance painting, for which he felt a particular fascination, is evident. His love for Italy would lead him on a journey along the peninsula in 1806, which is recorded through a series of nearly four hundred drawings made mainly in Milan and Rome. It will be during his first stay in Rome that he will have the opportunity to admire live the works of Raphael (Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520) and of the Italian Quattrocento, masterpieces that will have a decisive influence on his style. Also in Italy he would marry the young milliner Madeleine Chapelle in 1813. This was a fortunate period for the artist, who exploited his great skill in drawn portraiture, executing, despite the low regard he had for this genre, many portraits of members of the French and English bourgeoisie who resided in Rome.

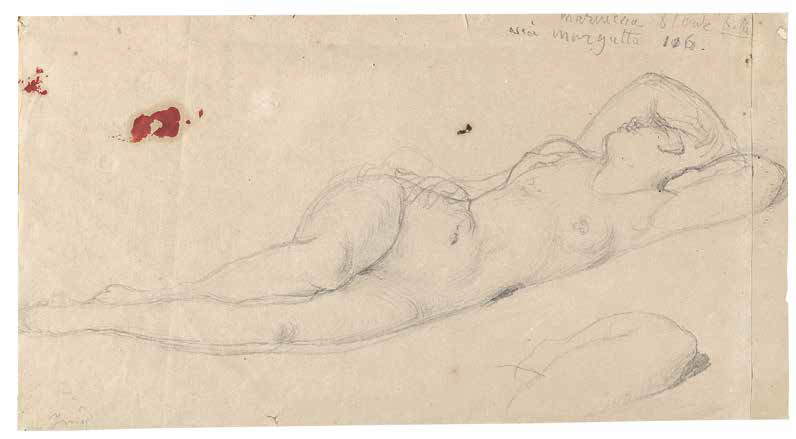

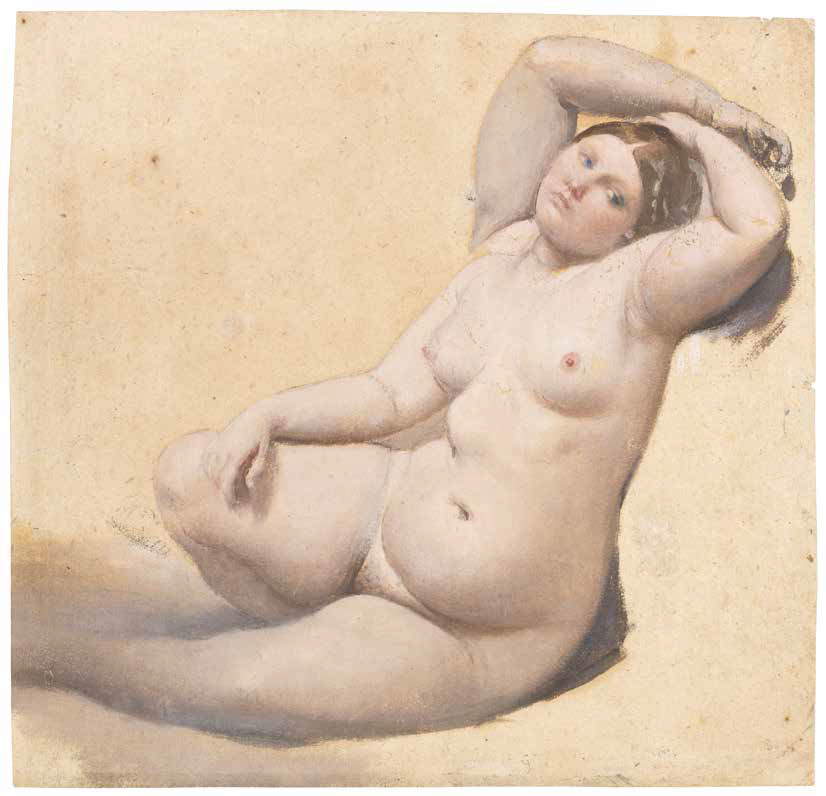

Another prominent personality who had influence on Ingres was Joachim Murat, who was appointed king of Naples by Napoleon in 1808. To Murat the artist sold a depiction of a “reclining woman,” known as the Sleeping Woman of Naples, intended for the small apartments of the Royal Palace. The original work went missing after the fall of Murat, but a preparatory drawing and a version preserved in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum are on display in the Milan exhibition. With the intention of commissioning a pendant of that reclining woman, Queen Caroline Murat, Joachim’s wife and Napoleon’s younger sister, commissioned Ingres in 1814 to create a back-paintedOdalisque, in addition to portraits of the Murat couple and their children. The requested odalisque is none other than the artist’s famous masterpiece, the Great Odalisque, and thanks to a letter written by Ingres himself we learn that the model for that painting was “a ten-year-old girl” from Rome: the scholar Dimitri Salmon proposes that she be identified with Atala Stamaty, a Roman born on August 11, 1803, who at the time of the making of the Great Odalisque was precisely ten years old. Fortunately Ingres, after the fall of Murat, managed to recover the famous masterpiece, which after several acquisitions would be purchased in 1899 by the national museums for display in the Louvre. Although the artist had a predilection for nudes, he did not have the same sympathy for anatomical science: in the Great Odalisque , in fact, a higher number of vertebrae than in reality is noted, causing an unnatural elongation of the back of the female figure depicted; in addition, the twisting of the neck and the shape of the breasts poking out from under the armpit are inverted. Nonetheless, the Great Odalisque is one of the most sensual figures in art history, and visitors to the exhibition will be captivated by it (it is present, however, in the grisaille version of the New York Metropolitan).

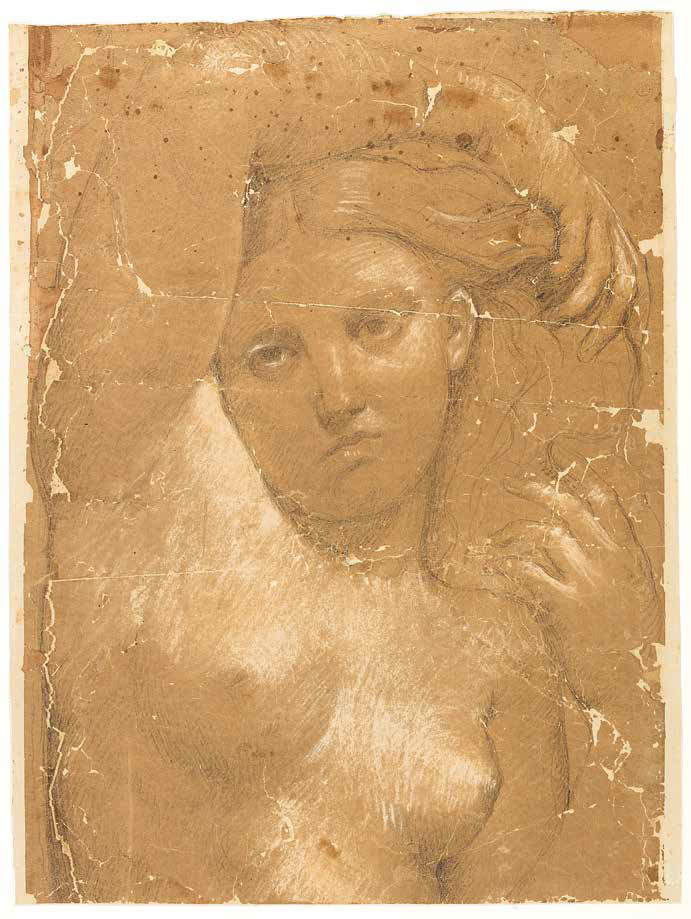

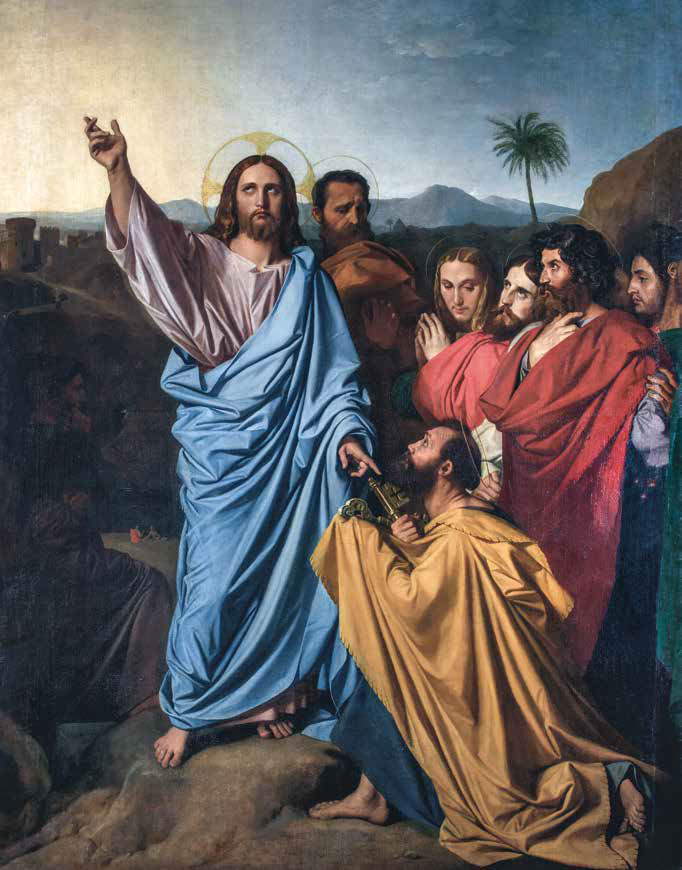

The female nude will be found in the last section of the exhibition, where studies for Venus Anadiomene relating to different parts of the body are on view, and in the study for the famous Turkish Bath , which features a sensual woman with three arms. In addition to this subject, the exhibition concludes with the presentation of a particular genre, called troubadour, which spread in France after the fall of the Empire thanks to Empress Joséphine, Napoleon’s wife, and Caroline Murat. Ingres devoted himself for a decade or so to this renewed historical genre, which brought to the canvas a new way of representing the national past by drawing on themes from the Middle Ages and the 16th and 17th centuries. Subjects of these paintings are painters and poets of the past and illustrious men, especially sovereign protectors of the arts. Belonging to the former is the series of paintings inspired by the life of Raphael, an artist who would represent a true “idol” for Ingres (even, on the occasion of the translation of the painter’s remains to the Pantheon in 1833, he would ask the pope for some bone fragments to be placed in a reliquary). On display here are Raphael ’s version of Raphael and the Fornarina fromOhio, as well as preparatory studies for several versions of this subject, and the Uffizi artist’s copy of theSelf-Portrait of the Urbino artist dating from 1823 kept at the Musée Ingres in Montauban. The painting Jesus Delivering the Keys to St. Peter and the large number of preparatory drawings of the latter make known the significant research work Ingres did onRaphael’s art, including examining some engravings with details of characters from one of the cartoons for tapestries made by the Urbino artist for the Sistine Chapel. In particular, Ingres focuses on the draperies and faces of the apostles.

More inherent to historical themes are L’Aretino and the Messenger of Charles V and The Death of Leonardo da Vinci: the former depicts the episode in which Charles V, on his return from Tunis, sends a gold chain to Aretino and the latter expresses his contempt by stating that it is a paltry gift; the latter, commissioned by Count de Blacas, an ambassador to the Holy See who intends to pursue a policy of aid for the artists who remained in Rome after the fall of the Empire, depicts the Da Vinci artist as he dies in the arms of Francis I. For the physiognomy of the French sovereign protector of arts and letters, Ingres was inspired by Titian ’s portrait of him (Pieve di Cadore, 1488/90 - Venice, 1576), similar in face and dress.

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Portrait of Lorenzo Bartolini (1805; oil on canvas, 98 x 80 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Grand Odalisque, grisaille version (c. 1830; oil on canvas, 83.2 x 109.2 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Study for the Dormition of Naples (q.d.; graphite on two papers, 14 x 26.4 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Study for Venus Anadiomene (c. 1808; pencil and white lead on vegetable paper, 47 x 24 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Woman with Three Arms, Study for the Turkish Bath (1816-1859; oil on paper, 24.9 x 25.9 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Raphael and the Fornarina (1814; oil on canvas, 64.77 x 53.34 cm; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Fogg Art Museum) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Copy of Raphael’sutoritratto (1820-1824; oil on canvas, 43 x 34 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Jesus Delivers the Keys to Saint Peter (1818-1820; oil on canvas, 280 x 217 cm; Montauban, Musée Ingres) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Death of Leonardo da Vinci (1818; oil on canvas, 40 x 50.5 cm; Paris, Petit Palais Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris) |

|

| Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, LAretino and the Messenger of Charles V (1815; oil on canvas, 41.5 x 32.5 cm; Lyon, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

There are thus two main objectives of this exhibition: to make the public understand how in reality Neoclassicism has a dual aspect and is not limited to mere formal purity, and to present an artist whose production was closely linked to theNapoleonic era, before and during its advent and after its fall. An artist who owes his success in large part to theinfluence of Italian art, also fulfilling his Italian campaign to achieve a leading artistic role in France. All this in a well-articulated exhibition that gives space for comparisons with other artists of the same context.

Also notable are the contributions in the accompanying catalog that deal with David’s artistic influence on his pupils and new interpretation of the neoclassical movement and the creation of a new iconography of empire with portraits of Napoleon. Although there is a lack of fact sheets on the works in the exhibition, small but thorough insights have been written that follow the exhibition in its different sections. In its totality, the exhibition contributes to the analysis of a particular era marked by a direct link between France and Italy.

The author of this article: Ilaria Baratta

Giornalista, è co-fondatrice di Finestre sull'Arte con Federico Giannini. È nata a Carrara nel 1987 e si è laureata a Pisa. È responsabile della redazione di Finestre sull'Arte.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.