by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 19/09/2016

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Being an Artist. Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti" in Carrara, Palazzo Binelli, from August 25 to September 22, 2016.

Article originally published on culturainrivera.it

Critics have only recently discovered the interesting figure of Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti (Florence, 1893 - Carrara, 1977), an artist who has always remained relegated to the margins of the best-known and most studied art history . Investigating the reason for this forgetfulness means retracing, in broad strokes, the artist’s own life: a woman from a noble family, the Mazzei family, ever present in the history of Florence, who married a Carrara marble industrialist (Carlo Fabbricotti) and spent substantially all her life devoting herself to the role of housewife, present wife and caring mother. In this context, painting has always constituted nothing more than an unpretentious divertissement . But not because Maria Theresa had no talent (far from it). As a teenager, when the artist developed her passion for painting, she merely attended the classes of Cesare Ciani, a postmacchiaiolo who helped improve her technique and who probably would have liked to direct her toward other masters and other experiences: however, the girl, framed from childhood within a strict Catholic education and moreover attentive to the traditional values of honor and prestige typical of the nobility, is not helped by her mother, who finds it disreputable that the master sometimes leaves his pupils alone with the models. And Maria Theresa is forced to stop attending Ciani’s atelier, who will give her lessons at home for some time, but the young woman sees the impossibility of seriously pursuing her painting studies as a condemnation to amateurism.

This condemnation, however, has not prevented her stature as an artist from emerging, albeit more than two decades after her death: in recent times, therefore, it has been all a sprouting of books and studies that have led to the first monographic exhibition dedicated to the artist, running until Sept. 22 in the rooms of Palazzo Binelli in Carrara, Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti’s adopted city. The exhibition, entitled Being an Artist. Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, curated by Alessandra Fulvia Celi, is a retrospective showcasing a substantial group of works from private collections, reconstructing almost the entire artistic parabola of the woman, from her beginnings that took place when Maria Teresa was about fifteen years of age, to the works of her maturity. Works that, after the disappearance of the artist, have remained mostly confined within the walls of the family homes and therefore hidden from the eyes of the public, which is now offered the opportunity to know more closely the tribulated history of an artist who could be pointed out as a glaring example of the condition of women in early twentieth-century society. A necessarily subordinate condition: Maria Theresa herself made no secret of the fact that the highest aspiration to which she was forced to aspire was to find what was usually called “a good match” with which to settle down and lead a secluded existence, devoted to the home, the church and the family. Ambitions from which art was necessarily excluded: hardly appropriate for a young woman from an aristocratic family, if not downright unbecoming, and if anything more suitable as a harmless pastime to be devoted to within the confines of the domestic walls.

|

| A room of the exhibition on Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti at Palazzo Binelli |

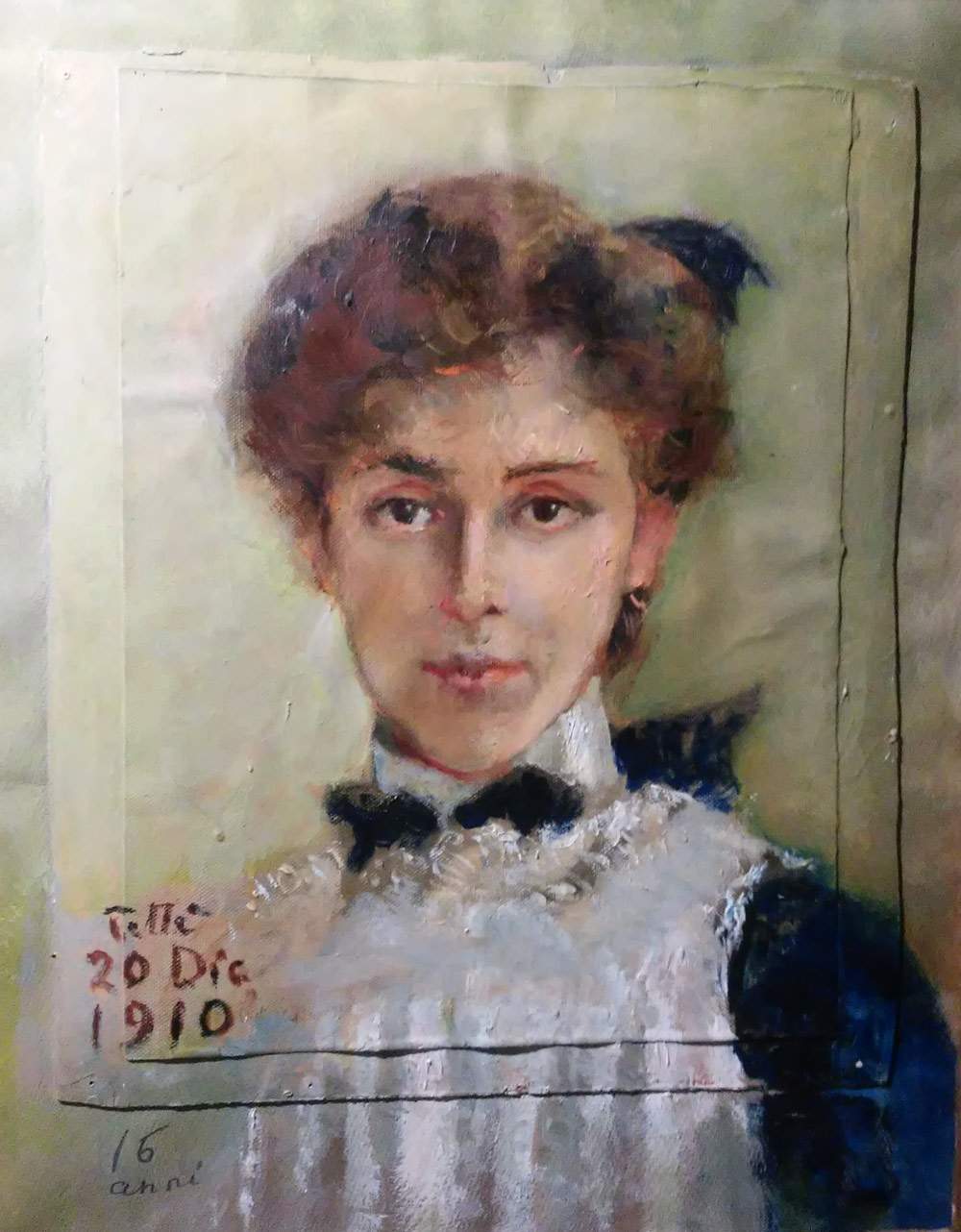

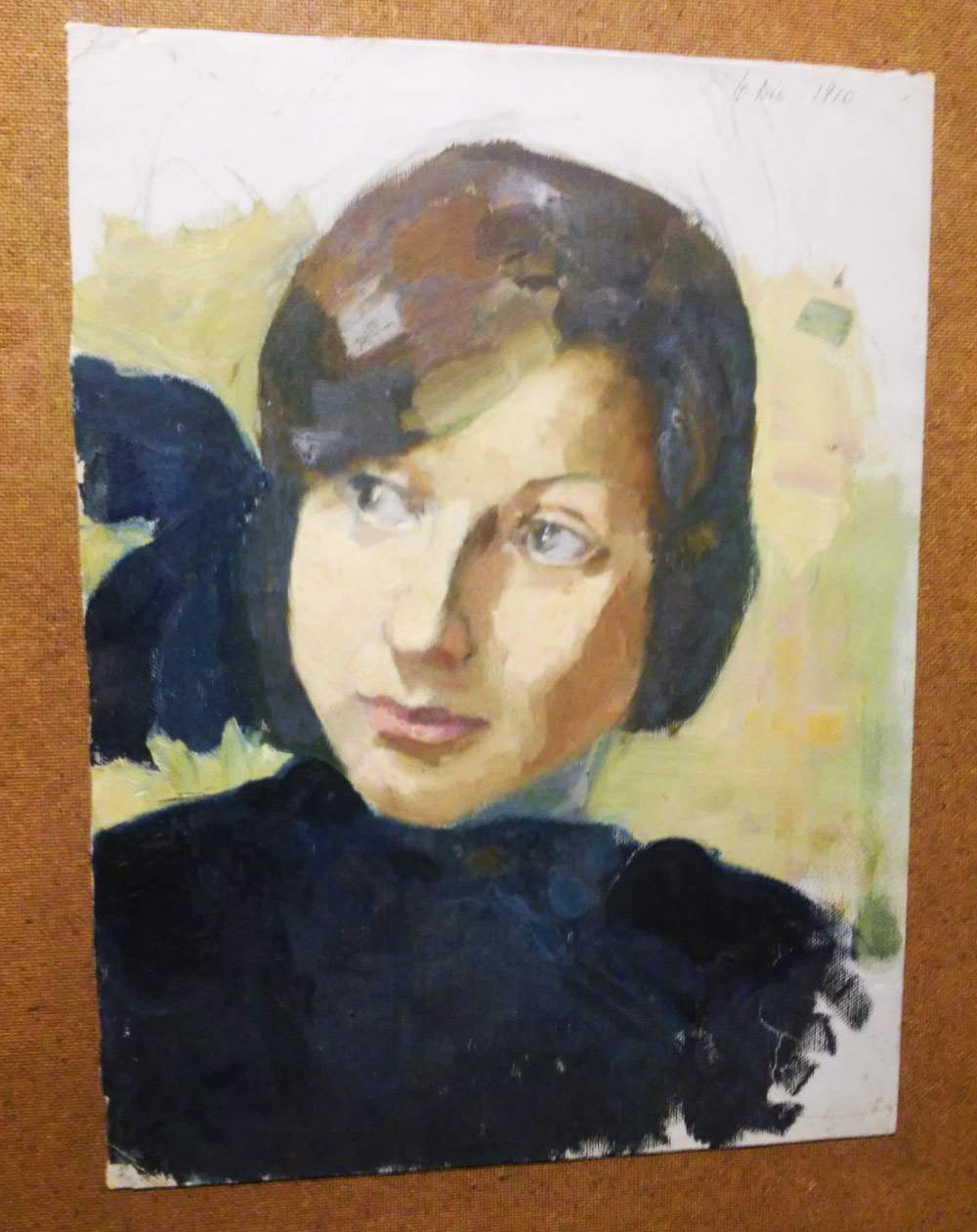

The exhibition’s chronologically unfolding itinerary begins in the 1910s, in a very specific place: the small village of Fonterutoli, in the Chianti region of Siena, the site of the summer stays of the Mazzei family, which still owns a vast estate in the area. Here, the young Maria Teresa, far from city life (as well as from prying eyes) can give vent more or less freely to her passion for art: given, however, the limited horizons to which the family obliged her, the number of subjects in her early youthful trials could only be reduced to two fundamental themes, namely her family members (and in particular her two siblings, Iacopo and Marie Antoinette, the latter affectionately nicknamed “Tottò”) and the landscapes offered by the verdant hills around Fonterutoli. We thus discover a sensitive artist, capable of making an expression come alive even with a few strokes of the brush, especially inwatercolor, the technique that is most congenial to her and in which she already seems to excel. Her first portraits reveal a technique that is still rather rudimentary (in theSelf-Portrait on Canvas of 1910 the drawing is uncertain and the colors are spread flat, almost ungainly), which, however, thanks in part to the lessons she learned, she will soon be able to evolve, giving rise to much more refined results. There is no shortage, however (albeit limited to watercolors) of interesting evidence, such as the portrait of his sister Marie Antoinette, also from 1910, in which the girl’s slender figure, rendered in an essential manner, is highlighted by patches of color that define her volumes. The tidy landscapes are influenced by the lesson of stain painting and, although lacking in luministic effects that give prominence and at the same time suggestion to the scene, they nonetheless reveal evidence of a sensitive hand and an eye that can somewhat intuitively capture atmospheric variations.

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “Self-Portrait” (1910; oil on canvas, 70 x 55 cm; private collection) |

|

| Above: Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “Portrait of Tottò” (1910; watercolor and India ink on paper, 24 x 19 cm; private collection). Below: Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “Tottò” (1915; watercolor on paper, 31 x 29 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “Tottò” (1910; oil on canvas, 51 x 41 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “Landscape of Fonterutoli” (1910s; watercolor on paper, 36 x 41 cm; private collection) |

The following decade was that of her marriage to Carlo Fabbricotti: the evolution of technique would, unfortunately, go hand in hand with the thinning out of the moments when Maria Teresa could devote herself to painting. From the date of her marriage, her mother-in-law had made things very clear: Maria Teresa would not be allowed to travel to Florence, where she would want to stay for long periods of time with the aim of continuing her studies (and let us not forget that Maria Teresa was an assiduous visitor to museums such as the Uffizi and Palazzo Pitti: the study of ancient painters, above all Bronzino and Andrea del Sarto, had constituted a founding moment of her artistic training). Her fate was to remain stationary between Carrara and Bocca di Magra (where the Fabbricotti family had a residence): thus thwarting her chances of maintaining contact with the Florentine artistic milieu. And then, between 1918 (the year of her marriage) and 1933, she will give birth to nine children: their birth can only sanction the definitive farewell to any artistic ambition other than that of an absolute amateur who finds in painting leisure and comfort from the anguish of life. Towards the end of the 1920s, in fact, the Fabbricotti family would experience disastrous financial reverses that would shortly bring it to the brink of bankruptcy: her husband Carlo would be forced to find new jobs and, in the 1930s, Maria Teresa herself would increase her artistic production with the hope of selling her paintings in order to scrape together some small income to offer her own contribution to the household economy. However, things would not go smoothly, and the modest economic results of her sales would not be enough to guarantee a decent livelihood for the family: it would be the intervention of her relatives, the Mazzei family, that would lift the family’s fortunes somewhat.

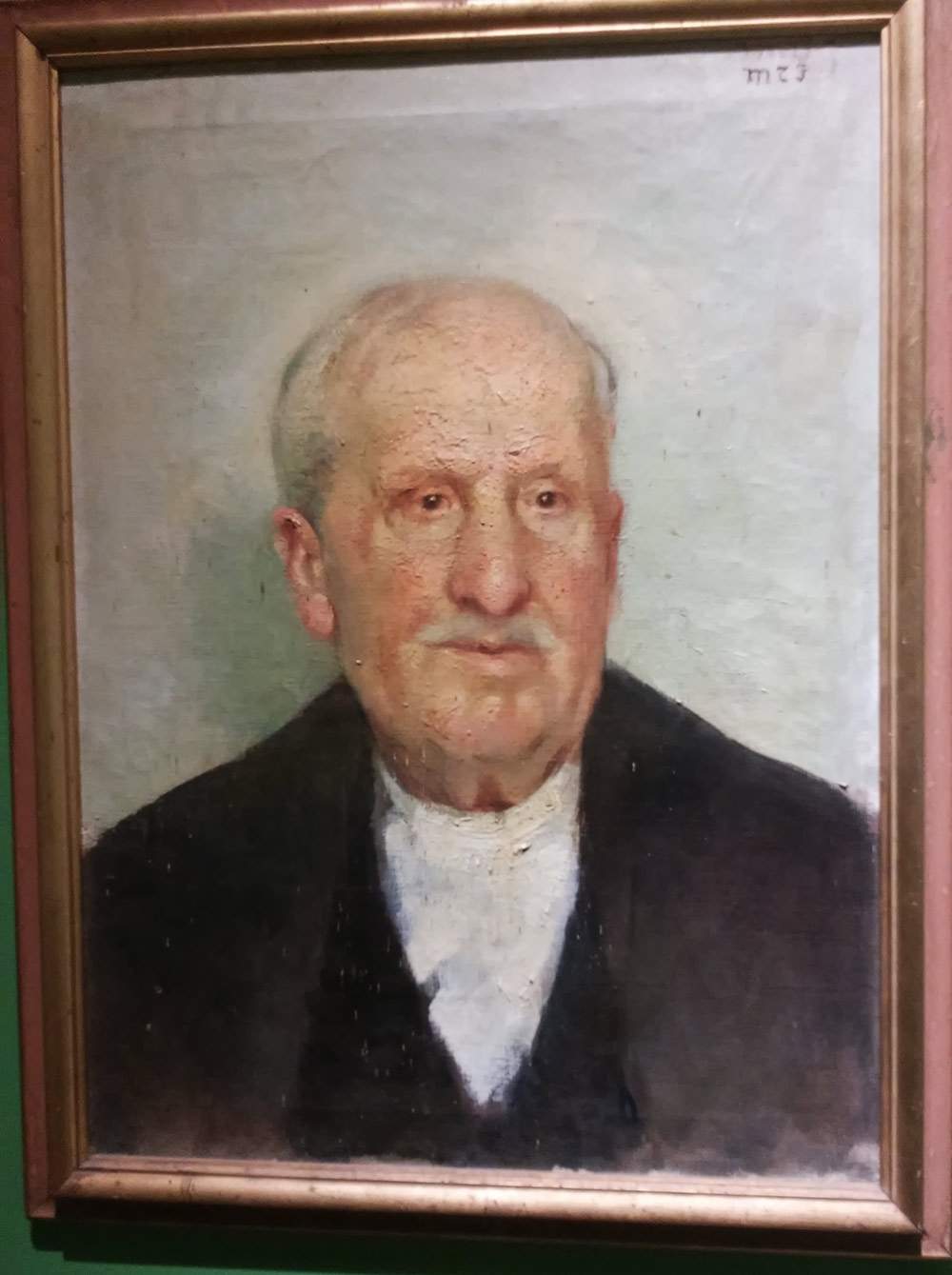

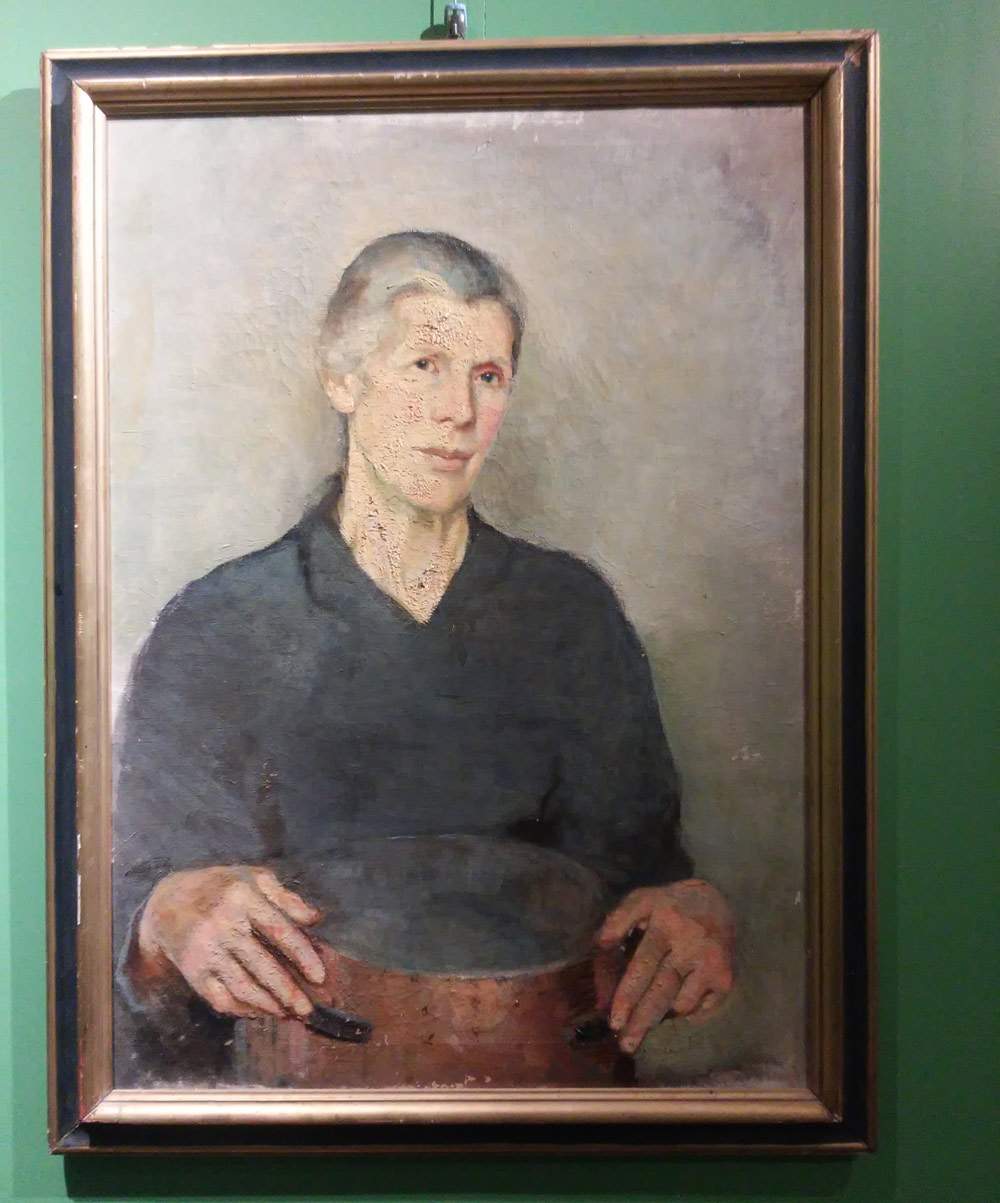

However, it is in this period that we witness some of the most interesting evidence of Maria Teresa’s painting, which makes enormous strides especially in her capacity for psychological introspection: her ability to capture the expression of the subjects she portrays proves increasingly vivid and intense. She chooses the “models” for her paintings from among the inhabitants of Carrara: but although she comes from a noble family and married one of the richest men in town, her sensibility leads her to be closer to the humble. Commoners, poor women, pensive old women, weary and fatigued workers become the undisputed protagonists of her art: perhaps, in those women with gazes clouded by a veil of melancholy, Maria Teresa almost glimpses of fellow travelers, creatures like herself condemned to a life not sought and not desired but nevertheless lived not with resignation, but rather with the spirit of one who knows how to find light, beauty and pleasure even when the fate she imagined was far different.

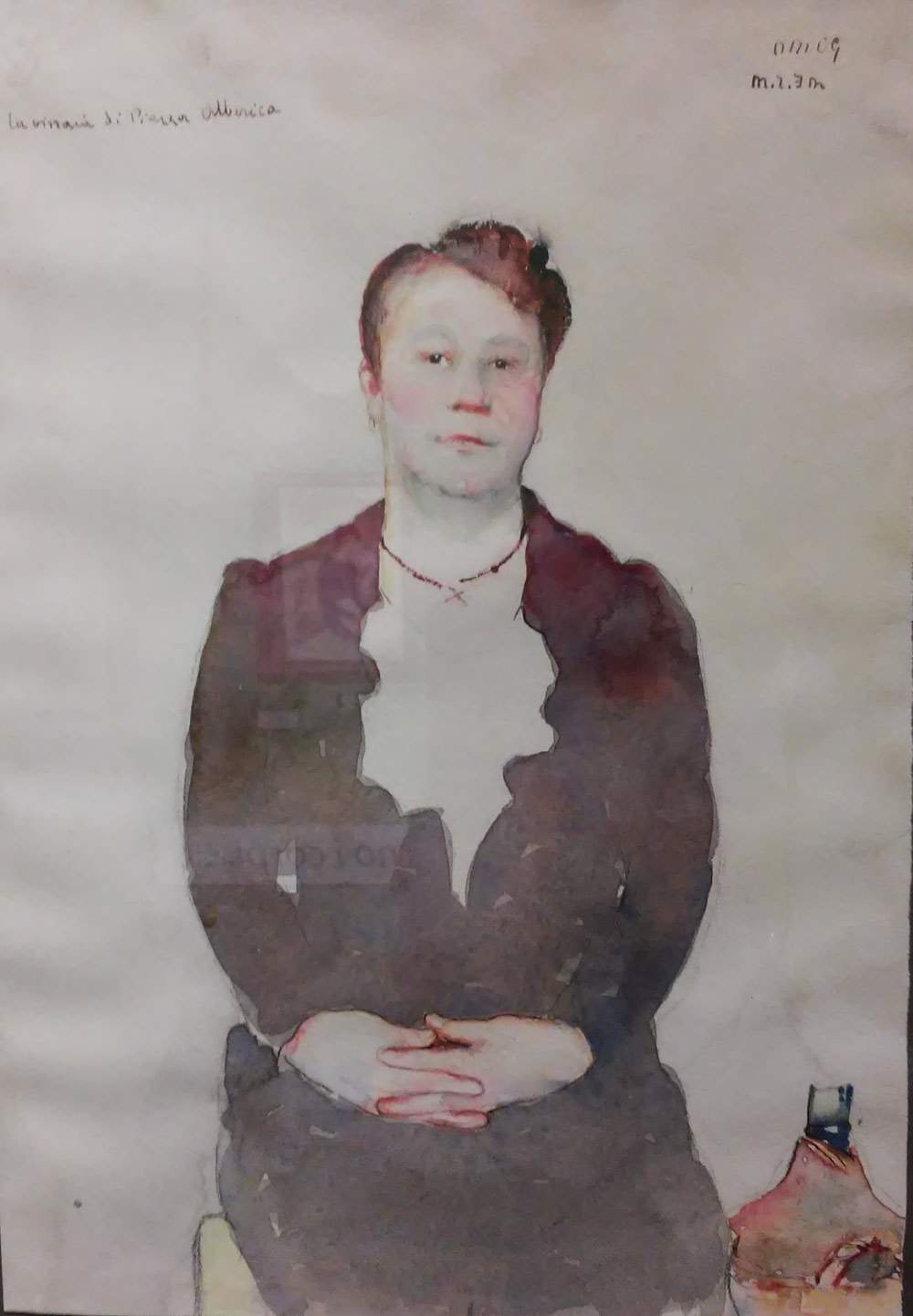

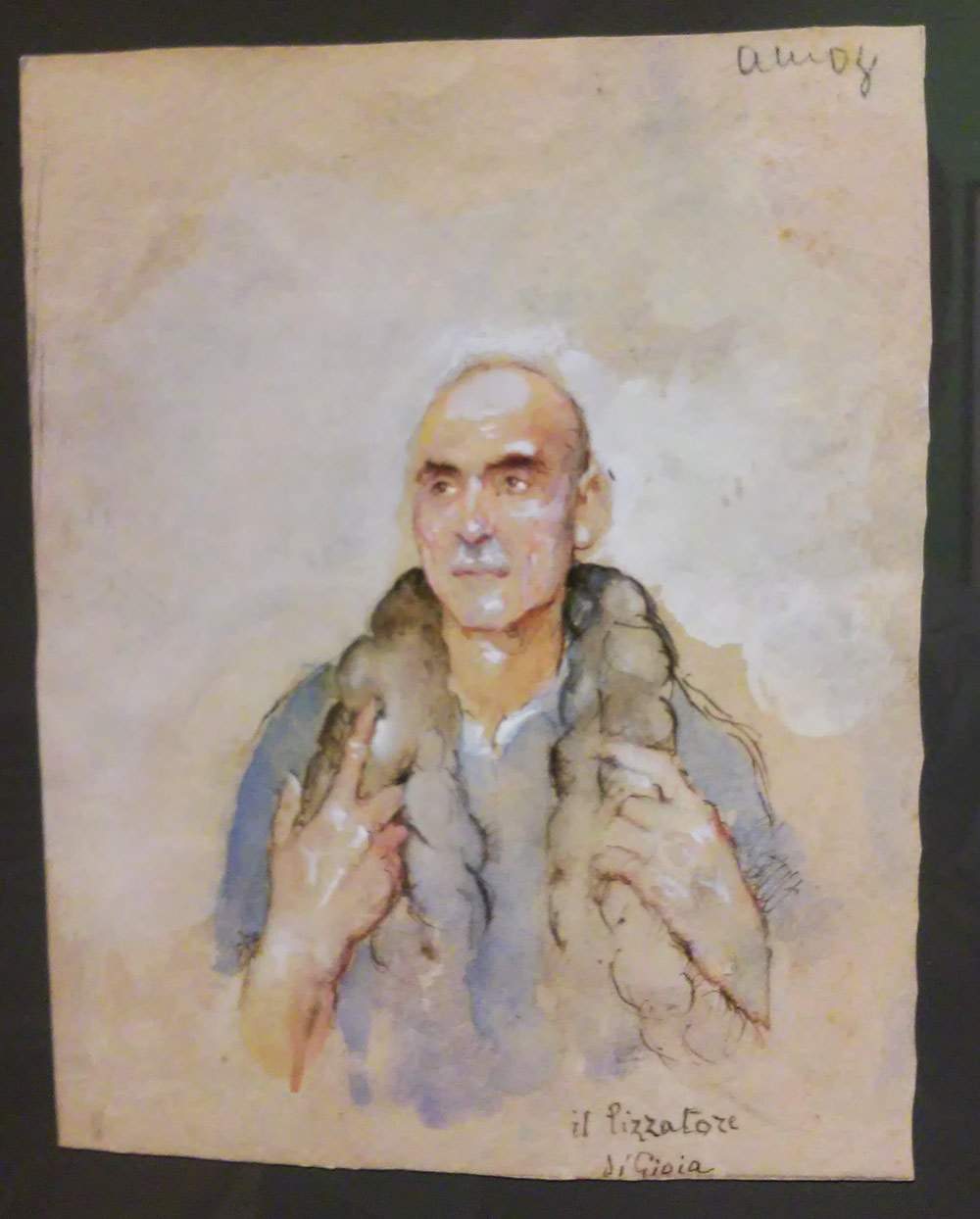

Thus were born such remarkable portraits as that of the Chairmaker, with which Maria Theresa in 1940 attempted to participate in the Venice Biennale (although the watercolor is, again, better than the oil on canvas painting: in the first case the Chairmaker appears more alive, more spontaneous, more natural, and this superiority of watercolors over oils affects almost all of the artist’s production), or again Gelsomina , which is sent in 1938 to a women’s painting competition in Sanremo, the splendid Vinaia di piazza Alberica caught in anexpression that reveals at the same time awkwardness about a situation (posing for a portrait) to which perhaps a wine seller was not accustomed, and pride arising from the knowledge that she had become the subject of a painting by a good artist, and again the Lizzatore with a hollowed-out face, or the Poor Woman with a disconsolate expression. These are all paintings that clearly manifest the goal of art according to Maria Teresa: "toknow the truth of human relationships." For Maria Teresa, the purpose of painting is to go in search of the truth: the result can only be a painting adherent to the truth, which seeks without mediation of any kind to capture the intimacy of the subject, to grasp the essential.

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “The Chairmaker” (1930s; oil on canvas, 73 x 56 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “Gelsomina” (1930s; oil on canvas, 100 x 76 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “A Poor Woman” (1930s; oil on canvas, 61 x 50 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “La vinaia di piazza Alberica” (late 1930s; watercolor on paper, 48 x 37 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “The Lizzatore” (1930s; watercolor on paper, 47 x 36 cm; private collection) |

|

| Various watercolors (the second from the left below is that of the Chairmaker) |

New sufferings would test Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti’s soul in the 1940s: the experience of war would be distressing and terrible, not least because one of her sons (Franco) would be captured by the Germans and imprisoned in a prison camp in Germany, from which he would nevertheless manage to escape. Letters remain to testify to the mother’s deep concern, and there is also an unfinished portrait, present in the exhibition, which Maria Theresa enriched, after her son’s return, with his prisoner’s name plate, imprinted with his serial number and the number of the Stalag to which he had been destined: atrocious testimony that serves almost as a warning, as well as a memory of what was perhaps the harshest experience of Maria Theresa’s life. The exhibition concludes with a wall entirely covered by the portraits of her nine children, arranged on two panels: vivid portraits, marked by a naturalism and fullness few other times touched by Maria Teresa, and which are pervaded by a motion of affectionate intimacy typical of a mother who always had an intense and very close relationship with her children.

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “La Carciofaia a Bocca di Magra” (1933; watercolor on paper, 37 x 39 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “La palma di Montia” (1950; watercolor and Indian ink on paper, 38 x 49 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “Portrait of Franco with Nameplate” (1940s; oil on panel, unfinished, 73 x 54 cm; private collection) |

|

| The nameplate on the portrait of Franco |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “The Elder Children” (1930s; oil on panel, 83 x 96 cm; private collection) |

|

| Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti, “The Minor Children” (1930s; oil on panel, 83 x 96 cm; private collection) |

Neither an original nor an innovative artist, but a superlative portrait painter endowed with a superlative talent, which was recognized even by some of the most distinguished artists and critics of the early twentieth century (the names of Arturo Martini and Ugo Ojetti would suffice, both of whom, moreover, agreed that watercolors were superior to oils: she had begun to exhibit, even arriving at a group show at Palazzo Strozzi, at a time when the contribution from the sale of the paintings had become necessary), Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti bears in her art the obvious signs of an inclination that was not adequately cultivated and supported: had she been surrounded by people endowed with a greater openness to the world, we might now be talking about another story. If in life she lacked thatemancipation which, to the roles of wife and mother she nevertheless ardently desired, would have added that of an established artist, it can nevertheless be said that it was in art that Maria Teresa Mazzei Fabbricotti found those moments of freedom that allowed her to express with overflowing passion and heated dedication her own nature and aptitudes. Especially in the portraits of women, as if the latter were painted in the guise of a mirror in which Maria Teresa saw her own soul and condition reflected.

This is an interesting exhibition and one worth visiting, because it takes us into the art and intimate world of an artist who remained unknown until not so long ago, but also because, in light of all the debates on the role of women in society, it sends out a strong message of stringent topicality. All in an itinerary, created with works all preserved in private collections (one more reason to visit the exhibition), careful to emphasize the main key passages of Maria Theresa’s artistic and human journey, creating a product therefore suitable for all audiences: the narrative is engaging, it proceeds without jumps and with adequate rhythms for an exhibition that unravels along five rooms. Too bad only that it lasts less than a month.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.