by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 16/10/2019

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Light and Silences. Orazio Gentileschi and Caravaggio's Painting in the Marche of the Seventeenth Century" in Fabriano, Pinacoteca Civica Bruno Molajoli, through December 8, 2019.

Among the episodes of Caravaggio ’s biography that are less frequented by scholars is perhaps the stay that the great Lombard painter made in the Marche region between October 1603 and April 1604: the product of those few months’ stay in the region, a canvas that was in the church of San Filippo in Ascoli Piceno and of which Longhi spoke “as an example at the limit of the possibilities of imagining an original by Caravaggio even from an extremely depressed and hasty copy” (since it was thanks to a copy that the scholar traced the painting’s existence), was lost after the Napoleonic spoliations. Michelangelo Merisi’s trip to the region had little effect on an area not yet willing to make itself receptive to the innovations that were being produced in Rome, but the news of his Marche excursion is useful for understanding the later development of Caravaggism in the area. The Marches and Rome, at the time, were in fact linked by a double thread: these were economic connections (the Marches was probably the richest and most productive region of the Papal States) and cultural ones, since a large number of artists and intellectuals left the lands beyond the Apennines to reach the capital, and the reverse route was often taken by the works produced in Rome by the greatest artists of the time to be sent to wealthy patrons in and around Ancona. Suffice it to say that, in the space of just four years, the region had experienced the aforementioned presence of Caravaggio, had been the destination of Guido Reni and Lionello Spada, who in 1604 went to Loreto to discuss the project for the frescoes of the new sacristy in the basilica of the Holy House (a commission that was later awarded to Cristoforo Roncalli), and in 1608 saw the arrival of one of Rubens’ masterpieces, the Nativity executed by the Siegen painter for the Oratorians of Fermo.

It was in this context that Orazio Gentileschi ’s (Pisa, 1563 - London, 1639) Circumcision arrived in Ancona: the artist from Pisa executed it in Rome in 1607 for an Ancona aristocrat, Giovanni Nappi, who had financed the construction of the Gesù church, the place for which the altarpiece was intended and where it is still kept today. The Ancona altarpiece is the first work Gentileschi painted for the Marche region and, in addition to providing an opportunity to recall the connections that existed at the time between the capital of the papacy and the region facing the Adriatic (Nappi was part of the Ancona delegation that traveled to Rome in 1605, and it is assumed that the artist came into contact with the wealthy nobleman thanks to Cardinal Claudio Acquaviva, Provost General of the Jesuits and a great lover of Tuscan artists), is also the ideal starting point for introducing the exhibition La luce e i silenzi. Orazio Gentileschi and Caravaggesque Painting in the Marche in the Seventeenth Century (at the Pinacoteca Civica di Fabriano until December 8, 2019), an important exhibition that has a twofold objective: to investigate in depth the terms of the painter’s presence in the Marche and to trace an itinerary of Caravaggism in the Marche, a region that, although not immediately associated as others (Lazio or Campania, for example) with the spread of the Milanese master’s lesson (essentially for two reasons: the short duration of Caravaggio’s stay in the area and the current absence of his works in the territory), was, on the contrary, affected by frequent Caravaggesque incursions, “both for autochthonous reasons, that is, for the presence of artists born within the borders, and for fortunate collecting or commissioning contingencies,” as Gianni Papi rightly points out in his catalog essay, dedicated precisely to the theme of Caravaggism in the Marche.

Although there have been recent reconnaissances of Gentileschi’s work in the Marche region (recall, for example, the one proposed by Livia Carloni on the occasion of the exhibition on Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi held in Rome, New York and Saint Louis between 2001 and 2002), never before had the artist’s role been placed in such close correlation with the artistic milieu that would shortly develop thanks in part to her fundamental contribution. To give an account of the novelty of the operation it is enough to think of the fact that never before had there been the opportunity for such a vast direct comparison between Gentileschi himself and the most illustrious of the Caravaggesque painters from the Marche, Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri (Fossombrone, 1589 - 1657), whose relationship with the Pisan has often been misrepresented, and the Fabriano review sets out to elucidate its nature in depth, taking care to well emphasize that independence of Guerrieri that so many times has not been taken for granted (far from it). But think also of the fact that the Fabriano exhibition, curated by Anna Maria Ambrosini Massari and Alessandro Delpriori, is the first ever dedicated to the “Marche Gentileschi,” as well as the first dedicated to the spread of Caravaggism in the Marche: not a single exhibition, one would say, but several paths that intertwine without, however, ever taking over one another (one of the merits of the exhibition lies, in fact, in its refined balance). In the end, an exhibition also significant for the various critical innovations that have emerged, and some of these will be attempted to be accounted for here.

|

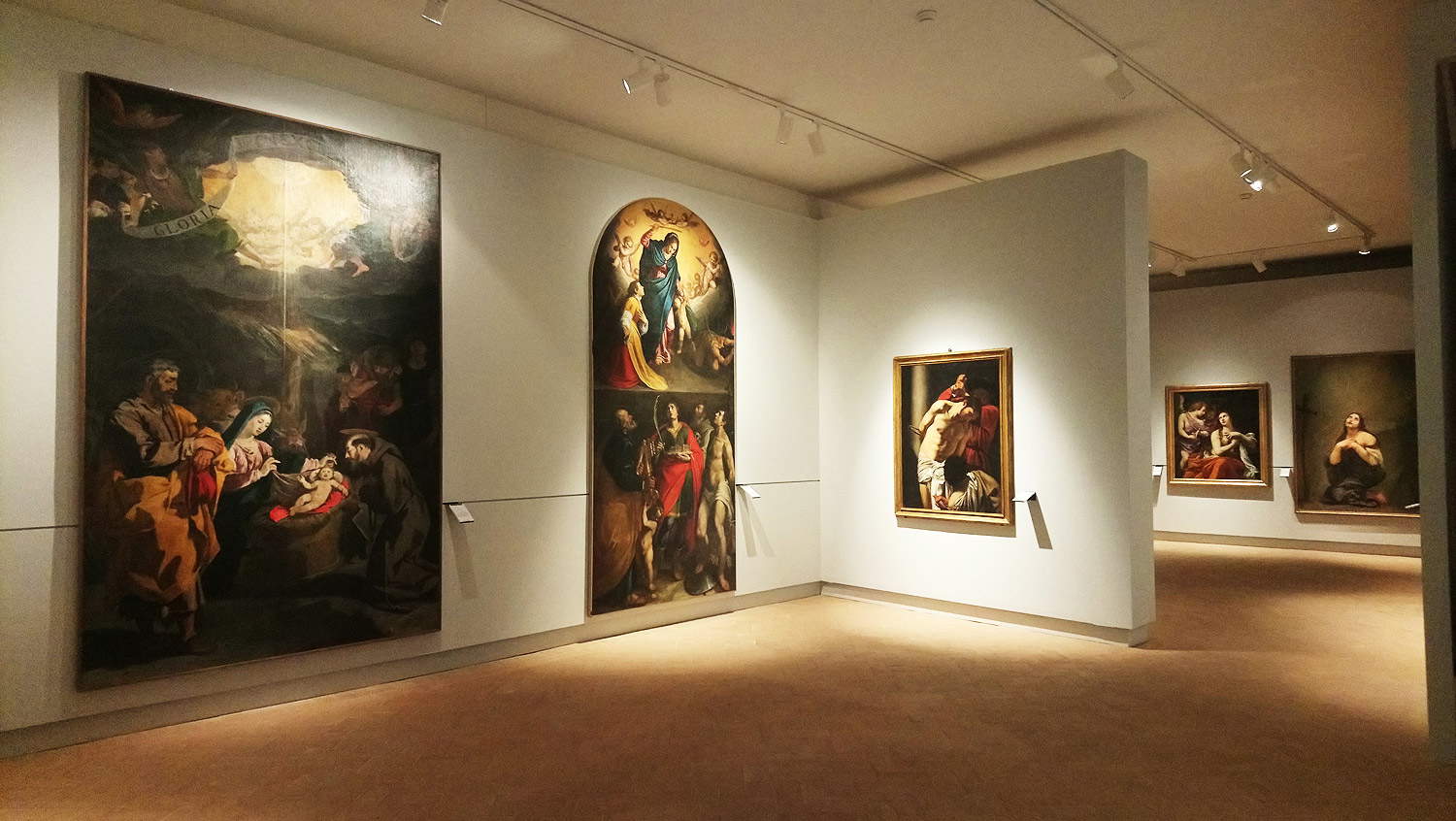

| Hall of the exhibition Light and Silences. Orazio Gentileschi and Caravaggio’s painting in 17th-century Marche. |

|

| Exhibition Hall The Light and the Silences. Orazio Gentileschi and Caravaggio painting in the Marche region of the seventeenth century. |

|

| Hall of the exhibition The Light and the Silences. Orazio Gentileschi and Caravaggio painting in the Marche region of the seventeenth century. |

There have recently been several exhibition occasions within which a physiognomy of the arts in the Marche towards the end of the sixteenth century has been delineated: it will suffice here to recall the 1992 exhibition Le arti nelle Marche al tempo di Sisto V, curated by Paolo Dal Poggetto, and the more recent Capriccio e Natura. Art in the Marche in the Second Sixteenth Century. Paths of Rebirth, the latter a product of the same curators of the Gentileschi exhibition in Fabriano (and consequently, by their own admission, the 2019 exhibition is a kind of continuation of it). The departure is therefore given to historical context, although the purpose is not to offer an exhaustive overview of art in the Marche in the late sixteenth century but, more in keeping with the goals of the exhibition, to put the public in a position to glimpse the branches on which Orazio Gentileschi’s art could graft itself. Artists who, in essence, were formed in the bed of the previous art, but knew the novelties that came from Rome, and albeit within the limits of their possibilities and their culture, were somewhat welcoming to them (although these were almost always limited and formal adhesions). Hence the absence of works by Federico Barocci or Federico Zuccari (who were also both in full swing when Orazio fired his Circumcision for Ancona), although it is impossible not to reckon, at least, with the reflections of their art: an example is the Nativity with St. Francis and Shepherds by Andrea Boscoli (Florence, c. 1564 - 1607), a work from the 1600s that opens the exhibition, and which is notable for its Baroque delicacy but also for the strength of its chromatic contrasts that anticipate new trends. The luministic vigor of Boscoli, a Florentine but adopted Marche native, becomes volumetric vigor in Andrea Lilli (Ancona? 1560/1565-after 1635): in his Forced Embarkation of the Family of Martha and Magdalene, the solid layout of the two figures on the left, depicted with a naturalism unusual for the Marche region of the time (the canvas, from the Basilica della Misericordia in Sant’Elpidio a Mare, is from 1602) and even placed by some (Arcangeli above all) in relation to the Caravaggio of the Contarelli Chapel (Lilli’s Caravaggism has long been debated), serves as a further forerunner for what was to emerge shortly thereafter with the arrival of Gentileschi and the birth of Guerrieri’s star. To complete the discourse on the antecedents (and “antecedents” is, moreover, the title of the first section of the exhibition) comes an altarpiece that is the result of the joint work of Filippo Bellini (Urbino, 1550 - Macerata, 1603) and the obscure Palazzino Fedeli (documented between 1603 and 1604), who completed the work following the urbinate artist’s overdue death: it is a Madonna del soccorso with Saints Vitus, Peter, Francis and Sebastian, painted between 1603 and 1604 (in the exhibition, scholar Lucia Panetti, following new archival research, has established that the execution was by Fedeli, obviously based on a drawing by Bellini: this is one of the novelties, since previously the altarpiece, from the collegiate church of San Pietro in Monte San Vito, was believed to have been executed entirely by Bellini). A simple, traditional, devotional iconographic structure (the Tridentine message took root strongly in the Marche region, a flourishing land of Counter-Reformation art) is lit up by a new luminism, with clear chiaroscuro contrasts, accentuated by a dense pictorial material, also in anticipation of the future seventeenth-century naturalism.

Gentileschi and the Caravaggesque artists come into the picture beginning in the second section, arranged thematically around the iconography of the Penitent Magdalene, with at the center, of course, the Magdalene that the artist from Pisa painted for the church of Santa Maria Maddalena in Fabriano on commission from the Università dei Cartai (and still stands there). We do not know exactly the period in which the painter executed his Magdalene: it is necessary to keep in mind, as Papi points out in the catalog, that the chronology of his Marche paintings is a difficult matter, and beyond the Circumcision, the only work that it is possible to date with certainty, many doubts remain (in fact, we have no certain evidence from documents). As for the Magdalene, several scholars agree on a date close to 1615, the year in which the Università dei Cartai was aggregated to the Roman archconfraternity of Santo Spirito in Sassia: we know that in 1612 Gentileschi was living in Rome, in the parish of Santo Spirito, reason for which it is assumed that some prelate, among his acquaintances, may have facilitated the commission. Gentileschi’s Magdalene, as Francesca Mannucci notes in the painting’s file, abandons “Mannerist sensualities” to rely on “a calm language” with which the artist “makes visible the act of redemption and repentance”: an intimate work, steeped in emotion, that declines with Gentileschi’s typical refinement (derived from his Tuscan training) Roman-Caravaggio’s naturalism. The room also introduces the figure of Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, with his Penitent Magdalene, signed and dated 1611 (although we do not know its original destination), which constitutes an immediate precedent for Gentileschi’s image and, at the same time, is already a declaration of independence vis-à-vis the art of the Pisan. Guerrieri, then 22 years old, was making his debut in his native land with this painting after spending some time in Rome, and in Rome he had the opportunity to catch up with Caravaggio’s revolution live: the Magdalene is among the first results of Guerrieri’s reflections. Guerrieri’s saint is far removed from the worldliness of Caravaggio’s Magdalene, but she is also immune to the languidities of the 16th-century Magdalene: she is a woman in sincere meditation, in a stark and somber setting, and her beauty is shaped by the light that stands out vividly against the shadow, in accordance with the most up-to-date Caravaggesque prescriptions (the Lombard, moreover, disappeared only a year before Guerrieri produced this canvas, one of his most splendid masterpieces). If elegance is Gentileschi’s most obvious hallmark, balance, on the other hand, is the characteristic that could best frame Guerrieri’s art.

Alongside these two extraordinary canvases, the curators have arranged, as mentioned, other works on the same theme to bring out affinities and divergences: so here parade before the public’s smug gaze the Magdalene by Guido Cagnacci (Santarcangelo di Romagna, 1601 - Vienna, 1663), unusually morose and resigned for the greatest champion of seventeenth-century sensuality (but we understand this if we consider that the canvas was intended for a convent of Benedictine nuns), that of Simon Vouet (Paris, 1590 - 1649), which, on the other hand, reveals much of its erotic potential (it was, after all, a painting destined for a private individual), and again the Magdalene by Simone Cantarini (Pesaro, 1612 - Verona, 1648) which, as is typical of the Pesaro artist’s manner, combines Caravaggio’s naturalism with the classicism of Reno (Emilian art was also often happily received in the Marche region) in a synthesis that probably had no equal. Finally, Guerrieri’s other Magdalene, a more sophisticated variant of that of 1611, deserves a mention; it also provides an opportunity to reason about the theme of copies and replicas, which were very frequent in seventeenth-century art as they were considered a formidable means of disseminating an artist’s ideas (and obviously the greater the number of copies and replicas, the greater the artist’s fortune: think of the subject of Caravaggio’s copies and how important they are to critics today), and the sensuous one by Giovanni Baglione (Rome, 1566/1568 - 1643), a testament to the fame the Roman painter had also achieved in Umbria and the Marches, as well as a painting rather illustrative of his manner ("one witnesses in this Magdalene,“ writes scholar Michele Nicolaci in the catalog, ”the happy synthesis of several stylistic registers, from the approach to the clear volumes of naturalist layout to a certain idealization of the female figure in the landscape of a more Reno and classicist tradition").

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, Circumcision with lEterno among angels and santa Cecilia playing the lorgano (1607; oil on canvas, 390 x 252 cm; Ancona, Church of the Gesu?). |

|

| Andrea Boscoli, Nativity with Saint Francis and Shepherds (1600; oil on canvas, 316 x 198 cm; Fabriano, Pinacoteca civica Bruno Molajoli) |

|

| Andrea Lilli, Forced Embarkation of the Family of Martha and Magdalene (1602; oil on canvas, 386 x 210 cm; SantElpidio a Mare, Basilica of Santa Maria della Misericordia) |

|

| Filippo Bellini and Palazzino Fedeli, Madonna del Soccorso con i santi Pietro, Vito, Francesco e Sebastiano (1604; oil on canvas, 350 x 160 cm; Monte San Vito, collegiate church of San Pietro apostolo, on deposit at the Pinacoteca diocesana in Senigallia) |

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, Saint Mary Magdalene Penitent (1612-1615; oil on canvas, 215 x 158 cm; Fabriano, church of Santa Maria Maddalena) |

|

| Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, Santa Maria Maddalena penitente (signed and dated 1611; oil on canvas, 185 x 90 cm; Fano, Pinacoteca San Domenico, Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio) |

|

| Guido Cagnacci, Santa Maria Maddalena penitente (c. 1640, post 1637; oil on canvas, 218 x 157 cm; Urbania, church of Santa Maria Maddalena) |

|

| Simon Vouet, Saint Mary Magdalene and Two Angels (c. 1622; oil on canvas, 136.6 x 112.4 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Simone Cantarini, Saint Mary Magdalene Penitent (1644-1646; oil on canvas, 178 x 204 cm; Pesaro, Musei civici) |

|

| Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, Santa Maria Maddalena penitente (mid-third decade of the 17th century; oil on canvas, 203 x 129 cm; Fano, Pinacoteca civica) |

|

| Giovanni Baglione, Saint Mary Magdalene Pen itent (1612; oil on canvas, 257 x 159 cm; Gubbio, Church of San Domenico) |

The room dedicated to the Magdalene also has the function of introducing some of the main protagonists of the exhibition: the discourse is expanded in the third and fourth sections, which constitute the highlight of the exhibition and, on the one hand, enter into the merits of Orazio Gentileschi’s relationship with the Marche region, and on the other, address the developments of Caravaggesque painting in the region. One of the high points of the exhibition is the wall displaying, side by side, Gentileschi’s Circumcision and Guerrieri’s Circumcision, the latter made for the church of San Francesco in Sassoferrato, where it still stands today. Gentileschi’s altarpiece reflects Titian’s precedents (as is well known, Titian also worked for Ancona), exudes a sumptuousness that is in keeping with the tastes of his wealthy patrons but also adheres to the preciosity that abounds in much of the Tuscan painter’s output, and is already imbued with realism (observe the faces of the protagonists: in this regard, it will be worth noting another of the exhibition’s novelties, namely the identification of a 14-year-old Artemisia Gentileschi in the Saint Cecilia playing the organ in the upper register, a hypothesis put forward by Lucia Panetti). Instead, it is Marina Cellini who establishes the terms of the comparison between Guerrieri and Gentileschi, resorting to Andrea Emiliani, who identified in the composition of the painter from Fossombrone a reworking of that of the Pisan, and placing in the quality of light one of the key elements to “measure the different aptitudes of the two artists,” the scholar points out: "for Carloni, the artist from Fossombrone engages his work with a light, incident, metaphysical, such as to make ’metallic everything that bathes,’ in antithesis to the crystalline light expressed in Gentileschi’s Circoncisione." Similar then is the composition, with the main characters arranged in the lower register, the opening onto the landscape behind them, the light coming from above. The journey among Gentileschi’s masterpieces then continues with the Virgin of the Rosary between Saints Dominic and Catherine, for which the latest research has moved the dating back in time (to about 1614: it would thus be one of the earliest works made in Fabriano), with the figures arranging themselves under the curtain like mute actors in a theater (here are the silences alluded to in the title), or with the Saint Francis Receiving the Stigmata, which is surprising for the finesse with which the artist succeeds in making palpable the mystical ecstasy of the saint invested by divine light (an admirable essay in Caravaggism reread in the light of the painter’s Tuscan substratum, cloaked in some Baroque accents, especially in the figure of St. Francis), and again with the Vision of St. Frances of Rome Receiving the Child from the Hands of the Virgin, where the figure of St. Frances of Rome is in direct relationship with St. Catherine of the Virgin of the Rosary (before the research conducted for the exhibition it was thought to be the other way around), and which represents one of the pinnacles of Orazio’s activity, not only of that of the Marche region. And this is for the intimate delicacy of the attitudes, for the ability to decline in a gentle, affectionate and elegant way Caravaggio’s luminism, for the measured composure of the characters, of Tuscan ancestry, almost neo-Renaissance, for that balanced relationship between form, light and colors in which Longhi saw Gentileschi’s “complexity,” understood as “scaled ratios of luminous quantities in colors; quantities that precisely because they are scaled become qualities of art: values.” A singular, almost protean Gentileschi is the one we then find in the David contemplating the head of Goliath, capable of reinterpreting a Rhenish model by infusing it with an unexpected mixture of monumentality and lyricism, for a David who, serious and frowning, meditatively observes the head of the enemy he has just defeated.

Walking through the rest of the large room that houses the third and fourth sections is equivalent to taking a tour of the great painting of the Marche region in the early seventeenth century, which begins with Guerrieri’sHercules and Onphale, the work chosen by the curators for the purpose of welcoming the public to this venue. And indeed, in this sort of introduction, we see a painter with a strong personality who offers us an exemplary summary of Caravaggesque painting in the Marche, in the meaning he himself elaborated: the lesson coming from Rome is grafted on a lively narrative taste, on an always balanced calmness, on a fine compositional balance, on a vast chromatic range, also because color in Guerrieri, Papi writes, “has a dominant role in the compositions, in some cases going so far as to shape them, leaving behind any design project.” The tendency to measure gestures and attitudes is a characteristic feature of almost all painters active in the Marche region: Guerrieri himself provides further evidence of this in the Cross with the Virgin, St. John the Evangelist and St. Mary Magdalene, which is also distinguished by the lively and varied colorism and the light that shapes, almost sharply, the beautiful faces of the characters, but mention could also be made in this regard of a painter who was not from the Marches and who did, however, work for the region, namely Antiveduto Gramatica (Rome, 1569 - 1629), whose Noli me tangere we admire in the exhibition, which on this very occasion was returned to him by Gianni Papi who has formulated his new attribution (as he did for two other paintings in the exhibition, one assigned to Angelo Caroselli and one to Antonio Carracci) on the basis of an interesting stylistic comparison with other known works by the Roman-Senese artist, pointing to the Noli me tangere as a demonstration of the “complexity of the painter’s inspiration” as well as of “his passion,” his “role in participating in the great changes of the third decade,” his “fidelity to naturalism” and his “fully accomplished openness to the new times.”

In Fabriano there is also room to clarify Giovanni Baglione’s role as a painter capable of spreading the language of Caravaggio’s art to the Marche region: an example of this is his Saint John the Baptist, which emerged just two years ago from a private collection and is being exhibited here for the first time (clear debts to the Lombard: for Michele Nicolaci Baglione is distinguished from his rival, however, not only by less sensuality, but also by his “more traditional and mannerist study of the figure, evidently already set through a graphic model and enriched later by the study from life of the model’s face in pose”). Baglione, capable of procuring important public and private commissions, was thus an important conduit for the Marche area, and the same role must have been exercised by the other artists who, from outside the region, sent their works to the Marche to replenish the collections of the wealthiest collectors or to decorate the churches of the area, serving as models for the local school. Visitors will thus find a sequence of works by great artists that testify to the great openness of the territory’s patrons: from a Madonna and Child with Saints by Bartolomeo Manfredi (Ostiano, 1582 - Rome, 1622), a very rare testimony to the Cremonese artist’s production of altarpieces, to the Holy Family with Saints by Carlo Bononi (Ferrara, 1569? - 1632), a painting with such a Venetian air that it was formerly assigned to Veronese, to the Death of the Virgin by Giovanni Lanfranco (Parma, 1582 - Rome, 1647), evidence of the Parma painter’s flourishing production in the Marche region, which contributed to the penetration of a little of his Carracci classicism, to the Miracle of the Furnace by Giovanni Serodine (Ascona, 1594/1600 - Rome, 1630), whose attribution was forcefully reconfirmed to the Swiss painter by Papi on the very occasion of the exhibition, to the French painters who had a certain fortune in the region: one example above all is Valentin de Boulogne ’s Saint John the Baptist (Coulommiers, 1591 - Rome, 1632), formerly owned by a doctor from Apirus. And the string of works by Valentin de Boulogne and Trophime Bigot is one of the peaks of the exhibition, especially by virtue of its intensity.

The concluding sections are devoted to “Caravaggesque questions” and to “a new saint, Saint Charles Borromeo” (these are the titles): in the penultimate room, the curators, in the laudable intent of making the public aware, with a title echoing Roberto Longhi’s studies, about the problems related to anonymous artists, emphasizing how exhibitions also serve to advance new hypotheses and probe new solutions, also offer some of the most interesting new works. One of the most important is certainly the identification of the so-called “Master of the Incredulity of St. Thomas” in the painter Bartolomeo Mendozzi (Leonessa, c. 1600 - ?, after 1644), made possible thanks to the work of scholar Francesca Curti, who achieved this result through precise and thorough archival research. On display in Fabriano are two works assigned by Curti to the artist from Rieti, who trained in Manfredi’s workshop and whom Papi, in outlining the personality of the then Master of Incredulity, defined as “a sort of alter ego of Valentin.” one of these is the so-called Madonna of the Salad, a rare depiction of the Rest from the return from the flight to Egypt (and not during the flight, as in the vast majority of cases), with Jesus, by then made almost a teenager, eating some bitter herbs (hence the name by which the work is identified) that allude to his fate. A work, Curti points out, that presents “a language of clear Caravaggesque matrix but updated to the Roman artistic innovations of the period” (i.e., of the fourth decade of the seventeenth century: “Lanfranchian suggestions and Cortonesque echoes,” the scholar specifies, “in the rendering of the vespertine light that pervades the landscape, the clouds on the horizon and the figures”). Providing an example of the “genius of the anonymous” (as per the expression used by the curators and the title of an exhibition curated by Papi in 2005) is a Trinity preserved at the Museo Pontificio della Santa Casa in Loreto, a canvas of very high quality, long present in the Marche region, and the work of an artist at the time unknown, perhaps local, but fascinated by early 17th-century Emilian painting. The concluding section is a thematic room devoted to the depiction of St. Charles Borromeo, which spread after his canonization in 1610. And since St. Charles Borromeo also protected against earthquakes, his cult spread rapidly and widely in the Marche region: Accompanying the audience to the conclusion are, among others, a masterpiece by Alessandro Turchi (Verona, 1578 - Rome, 1649), a Saint Charles Borromeo that is distinguished by its naturalism tempered by the painter’s cultured and expressive manner and the preciousness of his liturgical vestments, and a St. Charles Borromeo receiving the homage of the Petrucci couple in beggar’s attire by Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, where it is not difficult to catch a direct quotation from Caravaggio, from the Madonna of the Pilgrims, in the figure of the patron Antonio Petrucci kneeling at the saint’s feet.

|

| Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, Circumcision of Jesus (1614-1617; oil on canvas, 323 x 210 cm; Sassoferrato, church of San Francesco) |

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, Virgin of the Rosary between St. Dominic and St. Catherine (ca. 1614; oil on canvas, 291 x 198 cm; Fabriano, Pinacoteca civica Bruno Molajoli) |

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, Saint Francis Receives the Stigmata (c. 1618; oil on canvas, 284 x 173 cm; Rome, Church of San Silvestro in Capite) |

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, The Vision of Saint Frances Roman (1618-1620; oil on canvas, 270 x 157 cm; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche) |

|

| Orazio Gentileschi, David in Contemplation of the Head of Goliath (oil on canvas, 140 x 116 cm; Urbino, Galleria Nazionale delle Marche, Volponi Donation) |

|

| Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, Hercules and Onphale (c. 1617-1618; oil on canvas, 151 x 206.5 cm; Pesaro, private collection) |

|

| Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, The Cross with the Virgin Mary, St. John the Evangelist, and St. Mary Magdalene (c. 1615-1620; oil on canvas, 270 x 190 cm; Pesaro, Palazzo Montani Antaldi, Collezioni darte della Fondazione della Cassa di Risparmio di Pesaro) |

|

| Antiveduto Gramatica, Noli me tangere (1622-1623; oil on canvas, 294 x 183 cm; San Severino Marche, Duomo) |

|

| Giovanni Baglione, St. John the Baptist with Lagnello (c. 1610-1615; oil on canvas, 136 x 98 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Bartolomeo Manfredi, Madonna and Child between St. Mary Magdalene, St. Dorothy (?), St. Augustine, St. Francis of Assisi and St. Nicholas of Tolentino (c. 1615-1616; oil on canvas, 274 x 168 cm; Morrovalle, Church of St. Bartholomew the Apostle) |

|

| Carlo Bononi, Holy Family with Saint Charles Borromeo, Saint Francis, Saint Clare and Saint Lucy (c. 1627; oil on canvas, 330 x 200 cm; Milan, Pinacoteca di Brera) |

|

| Giovanni Lanfranco, The Death of the Virgin (c. 1627; oil on canvas, 252 x 158 cm; Macerata, Santi Giovanni Evangelista e Battista, Razzanti Chapel) |

|

| Giovanni Serodine, Saint Francis of Paola and the Miracle of the Furnace (1623-1625; oil on canvas, 273 x 130 cm; Matelica, San Francesco) |

|

| Valentin de Boulogne, Saint John the Baptist (c. 1628; oil on canvas, 135 x 100 cm; Apiro, collegiate church of SantUrbano) |

|

| Bartolomeo Mendozzi, Rest from the Return from the Flight into Egypt also known as Madonna dellInsalata (early fourth decade of the 17th century; oil on canvas, 248 x 169 cm; Recanati, Capuchin Church) |

|

| Emilia-Marchigiana trained painter, Saints Mary Magdalene and John the Baptist Adore the Holy Trinity with the Dead Christ (oil on canvas, 210 x 175 cm; Loreto, Museo Pontificio della Santa Casa) |

|

| Alessandro Turchi, Saint Charles Borromeo (1623; oil on canvas, 253 x 156 cm; Ripatransone, Cathedral) |

|

| Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri, St. Charles Borromeo Receives the Homage of the Petrucci couple in Beggars’ Clothing (second half of the third decade of the 17th century; oil on canvas, 214 x 145 cm; Fano, Church of San Pietro in Valle, on deposit at the Pinacoteca civica) |

The conclusion entrusted to St. Charles Borromeo is an invitation to ideally continue the visit of the exhibition in the churches of the city, which in fact form an integral part of it: Leaving the Pinacoteca and crossing the square to enter the cathedral of San Venanzio, the second chapel on the left will feature St. Charles Borromeo praying for the cessation of the plague, a controversial canvas by Orazio Gentileschi of uncertain date, which together with the paintings made for the chapel of the Passion (the canvas of the Crucifixion and the frescoes that adorn the room), St. Charles Borromeo in the church of St. Benedict and the Virgin and Child with St. Philip Neri in Glory by Guerrieri also kept in the cathedral, completes the itinerary imagined by the curators. It seems superfluous to point it out, but an exhibition is all the better the more it is rooted in its context, especially if it allows us to add knowledge on the subject, to give renewed impetus to studies on an artist or a topic, to formulate new hypotheses in the light of new research. Superfluous but perhaps not useless, if it is true that there is an increasing tendency to move and exhibit works without any real need and to fuel a tourism of works of art that is often devoid of merit. This is not the case in Fabriano: the exhibition at the Pinacoteca Civica is supported by a scientifically impeccable project, offers unprecedented comparisons, extends to the territory, restores Guerrieri’s distinct personality, traces a branched itinerary in Caravaggio’s painting in the Marche, gives the public an account of new discoveries (some of which have not yet been published: the study on Mendozzi is currently being printed), manages to maintain, without smearing, a high quality divulgative vocation (and in this sense the value of the section devoted to anonymous and attribution problems must be stressed) and, to crown it all, knows how to present itself to visitors with an extremely engaging approach.

Of course, it should also be pointed out that the body of research on Orazio Gentileschi is quite substantial, and that the Fabriano review comes after several exhibition occasions dedicated to the Tuscan painter: as reiterated in the opening, however, a focus on his activity in the Marche region was missing, all the more valuable in that it was ordered in the place where the artist lived roughly between 1613 and 1619. Consequently, such an exhibition was only possible in Fabriano, and the fact that the venue is peripheral does not mean that the level is not typical of a major exhibition. It will be convenient, therefore, to recall that the exhibition is dedicated to Andrea Emiliani, a profound connoisseur of seventeenth-century Marche art who died this year, who in the catalog of an exhibition devoted in 1988 to Giovanni Francesco Guerrieri praised the generosity of the “Italian province,” namely, the great scholar wrote, of the "most extraordinary reservoir of historical and artistic knowledge imaginable, the place of the encounter between the schools of the great cities (centers of power and irradiation) and this minute, vital, sensitive quota or level, or medium, of cultures of slippage or resistance, of autonomy or dependence: always high in revealing in every hamlet, or nearly so, born an artist; from every artisan, expressing felicitous expressive abilities; from every workshop, flourishing projects capable of engaging the hospitable, familiar and broad volume of churches ready to bring together and reveal the complex life of forms that has been created in that place over the centuries and that still expresses itself there: the only one that, in the whole world, can really do so." A nobility and complexity of the province that emerge in all their palpable evidence from the beautiful exhibition in Fabriano.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.