by Fabrizio Federici, published on 11/03/2021

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Two exhibitions in Rome, one on the relationship between Rome and Pompeii and the other on Roman archaeology in the Napoleonic era, allow us to explore the relationship between ancient and modern and reflect on what is being done today. Colosseum Arena included.

As the lapilli and ashes of Vesuvius submerged Pompeii, work on the construction of the Colosseum was nearing completion in Rome . This coincidence inspired the idea of setting up an exhibition under the arches of the amphitheater that traces four centuries of relations between theUrbs and the Campanian city(Pompeii 79 A.D. A Roman History, through May 9, 2021). An exhibition of great scientific rigor (the recently deceased archaeologist Mario Torelli played a leading role in its conception), from which visitors can learn a great deal: first of all, that Pompeii is not simply the “Roman city” buried by Mount Vesuvius, but a center with a long and complex history, with a strong local identity (evidenced by the use of the Oscan language) and with an interaction that was not always peaceful with Rome, which also saw moments of open confrontation, such as during the Social War, in which Pompeii was besieged and conquered by the Romans (89 BC.C.). The similarities between the social practices and artistic manifestations in the small town in Campania and in the large capital city, which naturally exerted a considerable influence on so many aspects of life in the Vesuvian cities, emerge well from the exhibition. And equally well do the differences emerge: in the province, luxury(luxuria) has a way of expressing itself with greater freedom even at the private level (see such landmark buildings as the Villa of the Mysteries and the House of the Faun), while in Rome luxury is approved only if it is intended for the public dimension(magnificentia); in Pompeii, interior decoration with colored marble is scarce (and triumphant instead in imperial Rome), to which cheaper frescoes are preferred.

The viewer thus has the opportunity, as mentioned, to learn a great deal, but he can also ’feast his eyes,’ for the exhibits are truly splendid: both those from Pompeii and the Archaeological Museum of Naples (from the fragments of a fictile frieze with jerking horsemen, from the early 3rd cent. BCE, placed at the opening, to the well-known mosaic with marine fauna, from the House of the Faun, to the polychrome stucco wall, found in the House of Meleager), as well as those illustrating the Roman scene (from the marble portrait of Augustus from the Baths of Diocletian, found in a villa in the Lunghezzina II area, to the polychrome marbles from the so-called Domus del Gianicolo).

Closing the exhibition is a re-enactment of the tragic end of Pompeii. A conclusion that raises some problems. First of all, because it is a natural calamity that adds nothing to a narrative about the relationship between Pompeii and Rome, and on the other hand it is clear that it is difficult to escape the ’obligation’ of staging a tragic and spectacular passage that visitors expect to see illustrated in any exhibition on the Campanian city. There is also a problem with the way in which this staging takes place: the terrible moments of the eruption are reconstructed in a well-done video, in front of which are placed three of the famous casts of the victims of the catastrophe, revealed toward the end of the video by beams of light. Casts are increasingly the subject of spectacle: this is on the one hand understandable, given their extraordinary dramatic nature, and yet one cannot overlook the fact that we are dealing, if not precisely with human remains, with umbrae of real lives and deaths that actually occurred that deserve pity even before astonishment. Perhaps one could haveavoided exposing them to public curiosity on this occasion, where their presence, in relation to the theme of the exhibition, seems entirely superfluous. Just as irrelevant (what does this have to do with Pompeii?) seems the choice of signaling the presence of the exhibition outside by ’plugging’ some of the arches with tarpaulins on which photographs of ancient statues are imprinted, suggesting the original layout of the exterior of the Colosseum (about which, moreover, we have no certainties).

|

| Exhibition layouts Pompeii 79 AD. A Roman History. Ph. Credit Alessia Cacciarelli |

|

| Set-ups of the exhibition Pompeii 79 AD. A Roman history. Ph. Credit Alessia Cacciarelli |

|

| Set-ups of the exhibition Pompeii 79 AD. A Roman history. Ph. Credit Alessia Cacciarelli |

|

| Bronze statuette of Lare (Trieste, Museo dAntichità J.J. Winckelmann) |

|

| Terracotta statue of Aesculapius (3rd-2nd cent. B.C. from Pompeii, Temple of Aesculapius; Naples, National Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Polychrome stucco wall (62-79 AD; from Pompeii, House of Meleager, tablinum 8, east wall; Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale, inv. 9595) |

|

| Fresco with fight scene between Pompeians and Nocerians in the amphitheater of Pompeii (59-79 AD; from Pompeii, House of the Fight in the Amphitheater, peristyle; Naples, National Archaeological Museum, inv. 8991) |

Rome and Pompeii

With the sudden destruction of Pompeii by Vesuvius, the exhibition comes to a close. But the relationship between the Campanian site and Rome does not stop, although the exhibition does not mention it. They disappear, it is true, for more than 1,500 years, but they resume as Pompeii and Herculaneum gradually re-emerge, beginning in the mid-eighteenth century. The impression produced by the excavations is enormous: for the first time, the Antique reappears in its purity, not ’bastardized’ by that centuries-old practice of reuse that had brought life back among the ancient walls and allowed its transmission, albeit at the cost of heavy adaptations. The relationship between the two cities of Campania and Rome is now reversed, compared to what is reconstructed in the exhibition: we are no longer dealing with the great capital influencing the social and cultural life of small towns, but rather with the emergence and gradual assertion of the idea of proceeding to a “Pompeization” of the Urbe. If two small towns had returned so many treasures, it was legitimate to expect far greater discoveries from a massive excavation activity in the Caput Mundi. It was legitimate, and indeed proper, to turn back the clock of History in search of irretrievable purity, and to free the ancient remains from the superfetations and neighboring constructions that suffocated them. This process did not begin immediately: the popes were too attached to the concepts of tradition and continuity to start turning Rome inside out. However, when Napoleon’s imperial eagle swirled over the Eternal City, the time was ripe to do as it did at Pompeii: the French were the bearers of the new even in the field of archaeology, and very little interested them in the protection of Christian memories and the vestiges of the “low centuries.”

Napoleonic archaeology

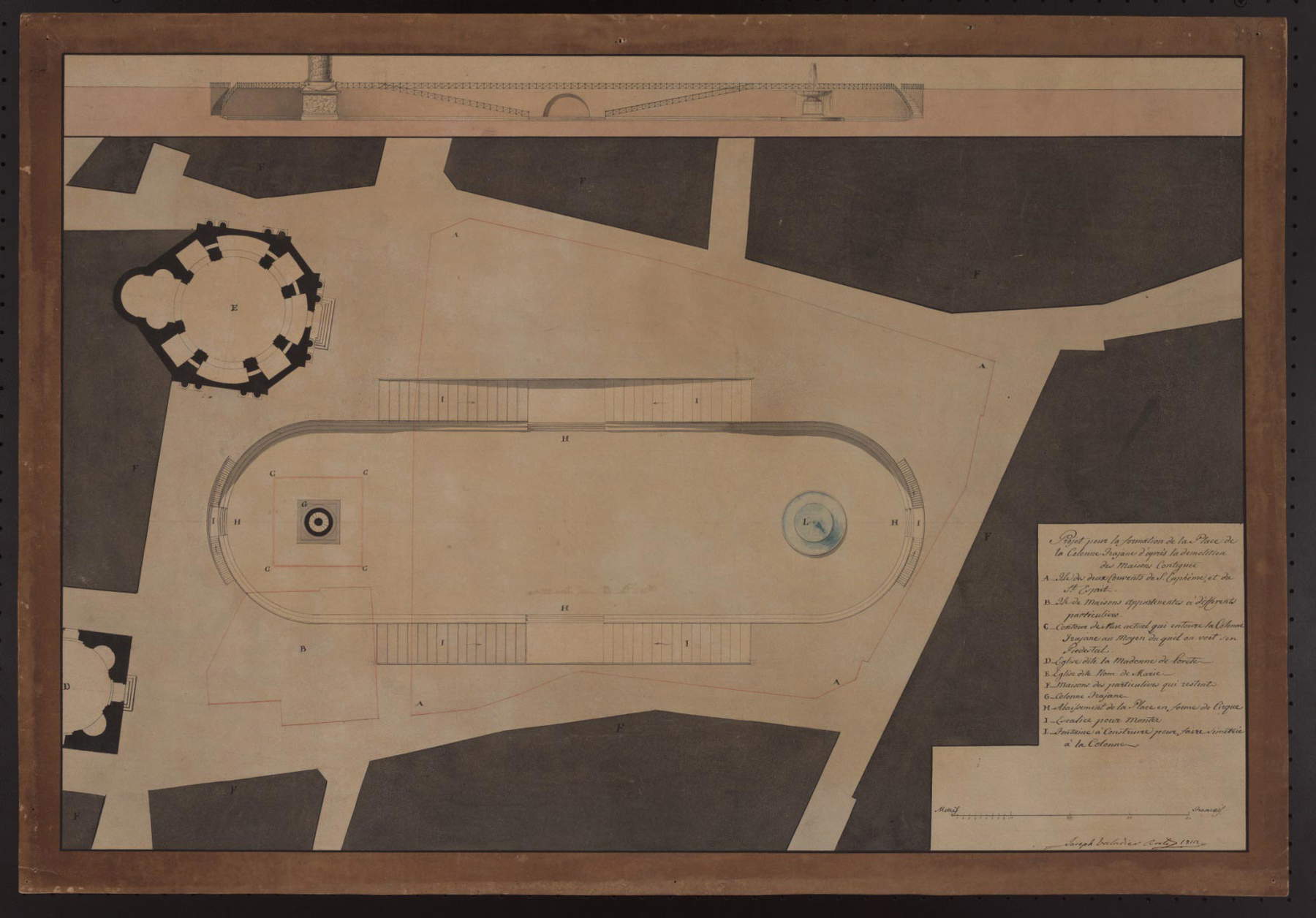

The exhibition Napoleon and the Myth of Rome, open until May 30 at the Mercati di Traiano, is dedicated to this fundamental juncture in the history of Rome and archaeology. The choice of the ancient complex as the venue for the exhibition is justified by the fact that the area of Trajan’s Column and the Basilica Ulpia, adjacent to the Markets, constitutes the setting in which the occupants wanted to experiment with a new way of understanding the relationship between archaeology and the city, between Ancient and Modern. The work of liberating the Column from the surrounding buildings, carried out in 1811-1812, was followed by the debate on the arrangement to be given to the large widening that resulted: the plans drawn up by Giuseppe Valadier (together with Giuseppe Camporese), which envisaged a majestic square, inserted into the surrounding urban fabric, were set aside in favor of the “museum of ruins” conceived by Pietro Bianchi, forerunner of the modern archaeological ’pits’ that dot Rome and many other cities. In the exhibition, the story of the excavations around the Column and the subsequent arrangement of the area is retraced through the display of a number of plans (in the original or through not always impeccable reproductions). The visitor is thus given the basic information to know and frame this affair, without, however, being enabled to appreciate the fundamental importance of the confrontation in the evolution of our relationship with ancient pre-existences in the urban sphere (it is impossible to say whether and how much this point is developed in the catalog, which is not yet available a month after the opening of the exhibition). Otherwise said, the exhibition could perhaps have chosen to adopt an admittedly less ’ecumenical’, but arguably more pithy slant, shrugging off the more generalist parts related to the figure of Napoleon, his biographical and political events, and the wide-ranging reconstruction of the French occupation of Rome, and focusing on the more specifically archaeological aspects. An exhibition that is certainly more difficult, but perhaps better able to marry with the context that welcomes it and, above all, to induce the viewer to new reflections on the past and the present. That said, many of the works on display are of great interest, as are the exhibition’s layout and graphic identity, due to Wise Design (of the imposing structure with cypress trees and mirrors that occupies the Great Hall, a reminder of the French love of green spaces and promenades, however, could probably have been done without).

|

| Exhibition layouts Napoleon and the Myth of Rome. |

|

| Giuseppe Valadier and Giuseppe Camporese, Project for the arrangement of the area south of the Trajan Column (1812; watercolor drawing; Rome, Accademia Nazionale di San Luca) |

|

| Charles Lock Eastlake, The Forum of Trajan after excavations by the French (c. 1820-1830; oil on canvas; Rome, Museum of Rome). Ph. Alfredo Valeriani |

|

| François Gérard, Napoleon in his coronation robes (1805; oil on canvas; Ajaccio, Palais Fesch-Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

|

| Eagle of the 7th Hussar Regiment (1804; gilded bronze; Paris, Musée de lArmée) |

With the settlement of the area of Trajan’s Column came that process of large-scale exhumation and isolation of the Ancient that lasted for at least a century and a half, reaching its peak with Fascism and its idolatry of ruins. A process that, while it brought enormous progress on the level of our knowledge of the classical world, also generated that generally accepted idea of ancient vestiges as something separate from the contemporaneity surrounding them, forever crystallized, dead. Undeterred, it took the path of scraping and isolating the ruin and morbidly displaying the bowels of the city (the intricacies of low walls that emerge here and there in the built fabric), discarding and then forgetting alternative design proposals, beginning with those of the aforementioned Valadier, whose words, rereading them today, are striking in their modernity and foresight. Defending in 1813 his own ideas for the arrangement of the area of Trajan’s Column, the great architect clarified the reasons that prompted him to oppose the “Pompeization” of Rome: reasons of a conservative order (“these discoveries, and leftovers remaining in the weather of time, it is not possible to preserve them [...]; since the rain waters, sun, grasses etc., however much custody one had, everything would go to detach, and perish”), but above all reasons related to the need not to interrupt the continuity of the fabric of the modern city (“it would become a whole between the modern surroundings, and the few ancient ruins very disgusting, and imperfect, and equally inconceivable. If then for a short time such a place remained neglected, it would become a s[t]herpetic, incompatible within the city for all relations.”). Valadier tries to rec oncile “the scrupulous maintenance of the ancient, which I revere as much as anyone, but without fanaticism” and the livability of the modern city. Therefore, with regard to the areas surrounding the square that was to surround the Column, located under the modern streets, Valadier suggests not to destroy the streets and widen the ’hole,’ as would be done later, but to allow the coexistence of ancient and modern, preparing hypogeal structures that would allow visits to the findings (“[...] under the streets, and where necessary I would continue the excavation, and making of the vaults above pillars, to preserve the modern floor of the streets, I would thus keep under cover all the rest of the floor, and the other parts, which might in this way be preserved forever.”).

Return to the Colosseum

The demolition fury of the fascist pick followed decades of embarrassed gridlock, with the excavations left to their own devices, and miles of fencing separating them from the living city. Public spaces inaccessible, or at best left to the exhausted grazing of tourists. Something, however, seems to be moving at last, in the direction of that recomposition of urban space hoped for by Valadier and of a more accomplished “social reintegration” of the Ancient. Thus we return to our starting point, to thatFlavian Amphitheater that hosts the Pompeii exhibition and will soon be equipped with a new arena, destined to restore the site ’only’ one hundred years (or so) after the archaeological excavations that destroyed the square enclosed between the tiers of seats. The ministerial decision to go ahead with the construction of a new arena has been the subject of fierce criticism, under the banner of misoneism, benaltrism (’well there is more to be done, other priorities: as if all the problems of our cultural heritage depended on the 18.5 million euros earmarked for the undertaking) and catastrophism (“here, they’re going to make Roma games there,” “the Colosseum will be disfigured”). The construction of a ’practicable cover’ of the monument’s basement actually has noble purposes: related to the purpose of restoring an overall legibility to the site, to the desire to protect the structures of the basement and facilitate its enhancement and popularization, through communicative apparatuses and displays that could not subsist in the open air, and related above all to the idea of allowing a fuller enjoyment of the cultural asset by citizens and tourists. Which does not mean denying the possibility of admiring the Colosseum itself, as a gigantic, silent, marvelous wreckage of a shipwrecked ancient civilization; but it does mean allowing it to be enjoyed in other ways as well , as a space intended for lectures, concerts and, why not?, well-done reconstructions of gladiatorial spectacles. With absolute respect for the ancient structures.

|

| A sign near the Baths of Diocletian |

|

| The Colosseum |

|

| The Ludus Magnus |

That of the Colosseum arena is of course but a small aspect of an overall ’Copernican revolution’ that must concern our approach to archaeological heritage in urban settings. Let us begin, in the meantime, with the star of Italian and world sites, and then, if the experiment bears fruit, we can move on to consider places and structures of far greater visibility. Such as, to take just a few steps outside the amphitheater, the Ludus Magnus, the gladiatorial gymnasium whose remains lie in a condition of worrying neglect, sunken in and unworthy of a glance by passersby and motorists scurrying along the confines of the ’trench’ that houses the ancient structures. It would be a dream to see this area reclaimed for public enjoyment by means of an overlay of the excavations that would result in the creation, at the level of the current ground level, of a vast plaza, and allow, at the hypogean level, optimal enjoyment of the vestiges and their better protection. Perhaps reopening the ancient gallery that connects the amphitheater to the gymnasium, thus fully reintegrated into the complex of the most visited archaeological site in the world.

Intervening is necessary: because the millennial history of ancient buildings and archaeological areas, made up of periods of splendor, abandonment, reuse, restoration and anastylosis, did not end a few decades ago with their reduction to non-places; and because we want to be an active part of this history. On the occasion of the inauguration of the Colosseum, Martial wrote that Rome was restored to itself (“Reddita Roma sibi est,” Liber spectaculorum, II, 11): the grandiose public building marked the restitution to the people of a large area that Nero had appropriated. Similarly, there is a need today to reddere ancient monuments to the citizenry, focusing on their reintegration into the urban fabric and on a more complete and diversified fruition, contemplating uses that go beyond mere accessibility for tourist purposes.

The author of this article: Fabrizio Federici

Fabrizio Federici ha compiuto studi di storia dell’arte all’Università di Pisa e alla Scuola Normale Superiore. I suoi interessi comprendono temi di storia sociale dell’arte (mecenatismo, collezionismo), l’arte a Roma e in Toscana nel XVII secolo, la storia dell’erudizione e dell’antiquaria, la fortuna del Medioevo, l’antico e i luoghi dell’archeologia nella società contemporanea. È autore, con J. Garms, del volume "Tombs of illustrious italians at Rome". L’album di disegni RCIN 970334 della Royal Library di Windsor (“Bollettino d’Arte”, volume speciale), Firenze, Olschki 2010. Dal 2008 al 2012 è stato coordinatore del progetto “Osservatorio Mostre e Musei” della Scuola Normale e dal 2016 al 2018 borsista post-doc presso la Bibliotheca Hertziana, Roma. È inoltre amministratore della pagina

Mo(n)stre.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.