Four words, aphoristic, lapidary and forceful, express the credo Leonardo Dudreville would profess from the 1920s onward: “clear ideas, clearly expressed.” Clear ideas, vigorously rejecting previous abstract research. Clearly expressed, to welcome the conversion to a newfound objectivity, in the sign of a representation aimed at seeing things for what they are, and for which Dudreville, in 1921, would use an even more epigraphic definition: “realism.” Three years later, the renewed Dudreville on the path of clear and clearly expressed ideas would exhibit at the Venice Biennale, with the other sodalists of the Novecento group: Ugo Nebbia, reviewing the exhibition in Emporium (the Venetian painter had brought there an almost four-meter wide canvas, Amore - Discorso primo, now in the Cariplo collection), acknowledged that Dudreville had openly manifested, with that challenging painting of his, “his intentions of wanting to describe everything to us, even with the sacrifice of his art,” and recognized in it “his own good qualities of a painter precise and sure in his objectivism.” The Dudreville from the 1920s onward, the Novecentist Dudreville, is perhaps the one most familiar to the public who frequents exhibitions devoted to the art of the early part of the 20th century; he is the one who is sometimes mentioned even in manuals, as a founding member of the sodality that moved under the auspices of Margherita Sarfatti.

The germ of Novecentist research is to be found in that Manifesto against all returns to painting that Dudreville signed in 1920 together with Achille Funi, Luigi Russolo and Mario Sironi, and which announced the entry into a “period of firm and sure constructionism” with the aim of “making the synthesis of analytical deformation, with the knowledge and penetration acquired by means of all our analytical deformations.” This is where the most studied and best-known phase of his career begins, and here, in contrast, comes the exhibition Leonardo Dudreville and New Tendencies, the show curated by Francesco Parisi that the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca is dedicating to the artist, taking a look, however, at everything that came before that manifesto: the Divisionist Dudreville of the early days, the Dudreville approaching futurism, the Dudreville founder of the New Tendencies group, the avant-garde Dudreville, the synaesthetic Dudreville. Fifteen years of activity, between 1904 and 1919 (this is the period on which the exhibition focuses), during which the artist experimented, entertained relations with the Milanese artistic milieu, and initiated projects aimed at presenting himself as an alternative to the academy and at the same time paying off debts to futurism, with which, however, the experience of Nuove Tendenze would continue to have tangencies that were difficult to sever.

Four sections introduced by an antechamber that introduces Dudreville to the public and closed by a documentary epilogue: in between, a series of paintings, drawings and sculptures that not only reconstruct the multifaceted artistic and cultural itinerary of the young Dudreville, but also cast his experience in a well-defined context, which is proposed in the exhibition with a path that is distinguished by its scientific solidity and the pioneering nature of the project, in line with what is appropriate for a research center such as the Ragghianti Foundation. Unpublished works, rare works, significant scholarly novelties (including the first extensive reconnaissance of the exhibition of the Rifiutati del Caffè Cova of 1912, for which a section of its own is reserved), the collaboration with the Dudreville Archive to bring to Lucca significant, unusual, hard-to-see works, fascinating even for those who might arrive at the exhibition without having even heard of its protagonist: the Ragghianti Foundation welcomes an exhibition that constitutes an unquestionable advancement for studies on early twentieth-century art, but it is also an opportunity to deepen one’s knowledge of one of the most singular artists of his time, not least because the variety of his interests allows for a rather wide-ranging look at the events of the Italian arts in the period prior to the deflagration of the First World War. And it consequently results in a well-enjoyable, as well as scientifically inapposite, exhibition.

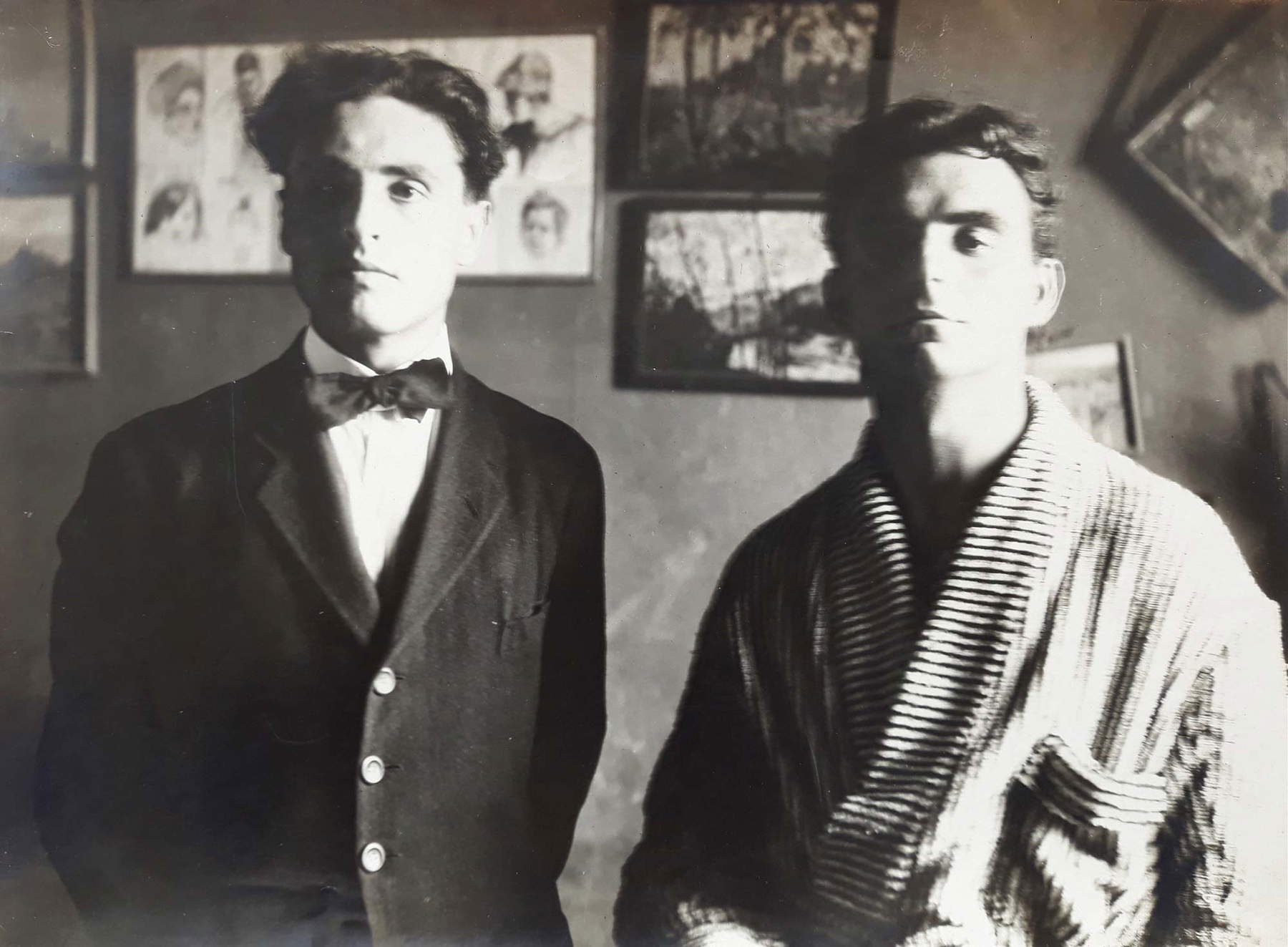

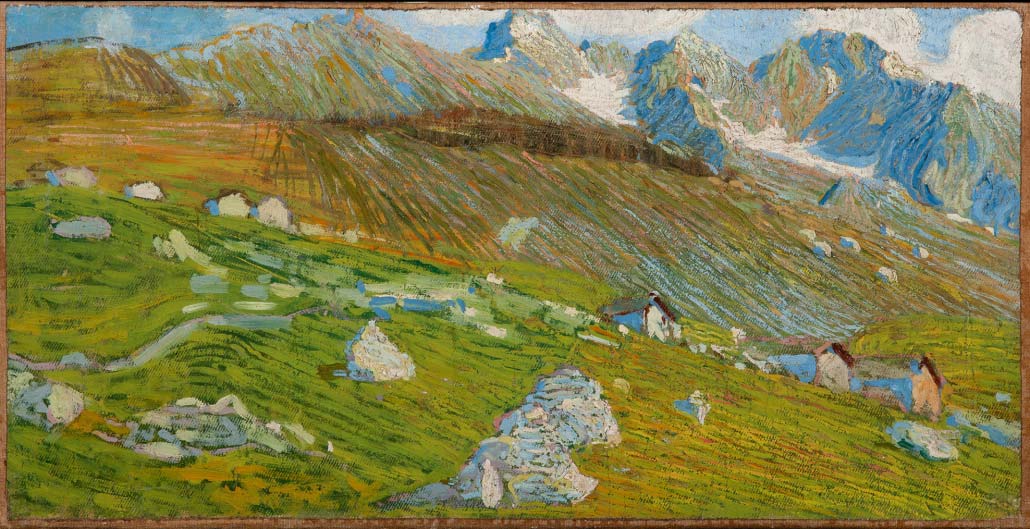

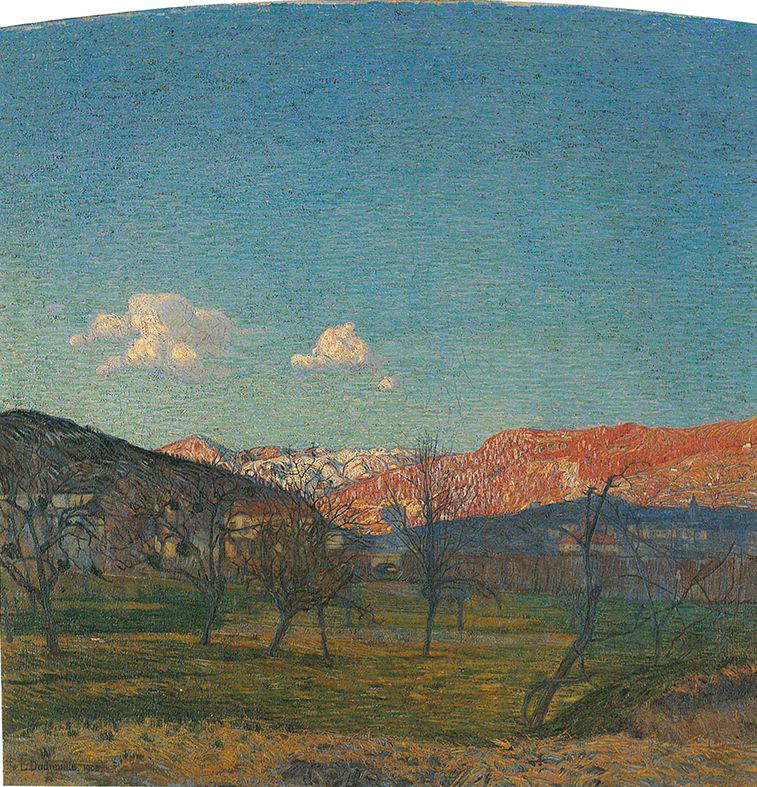

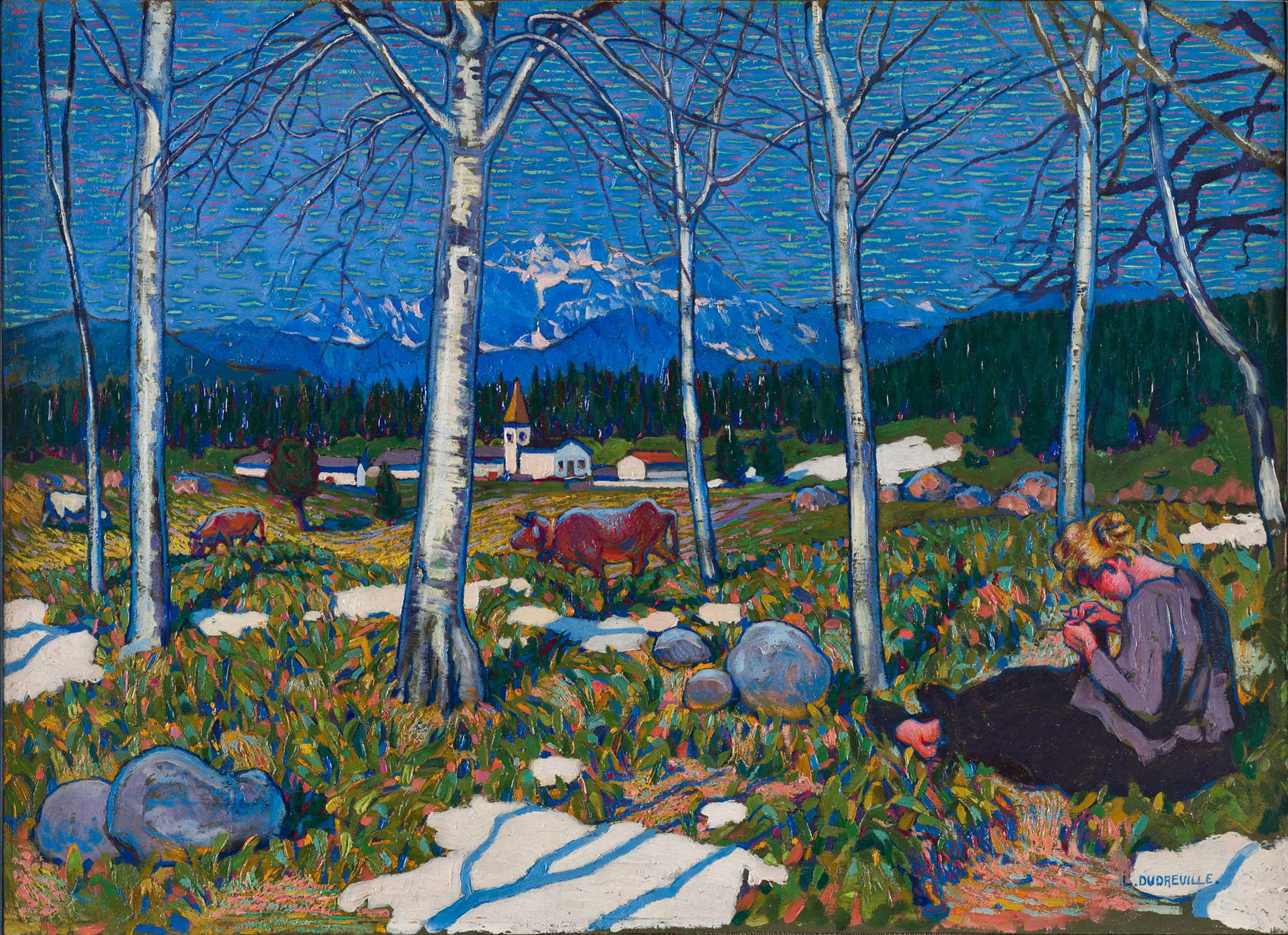

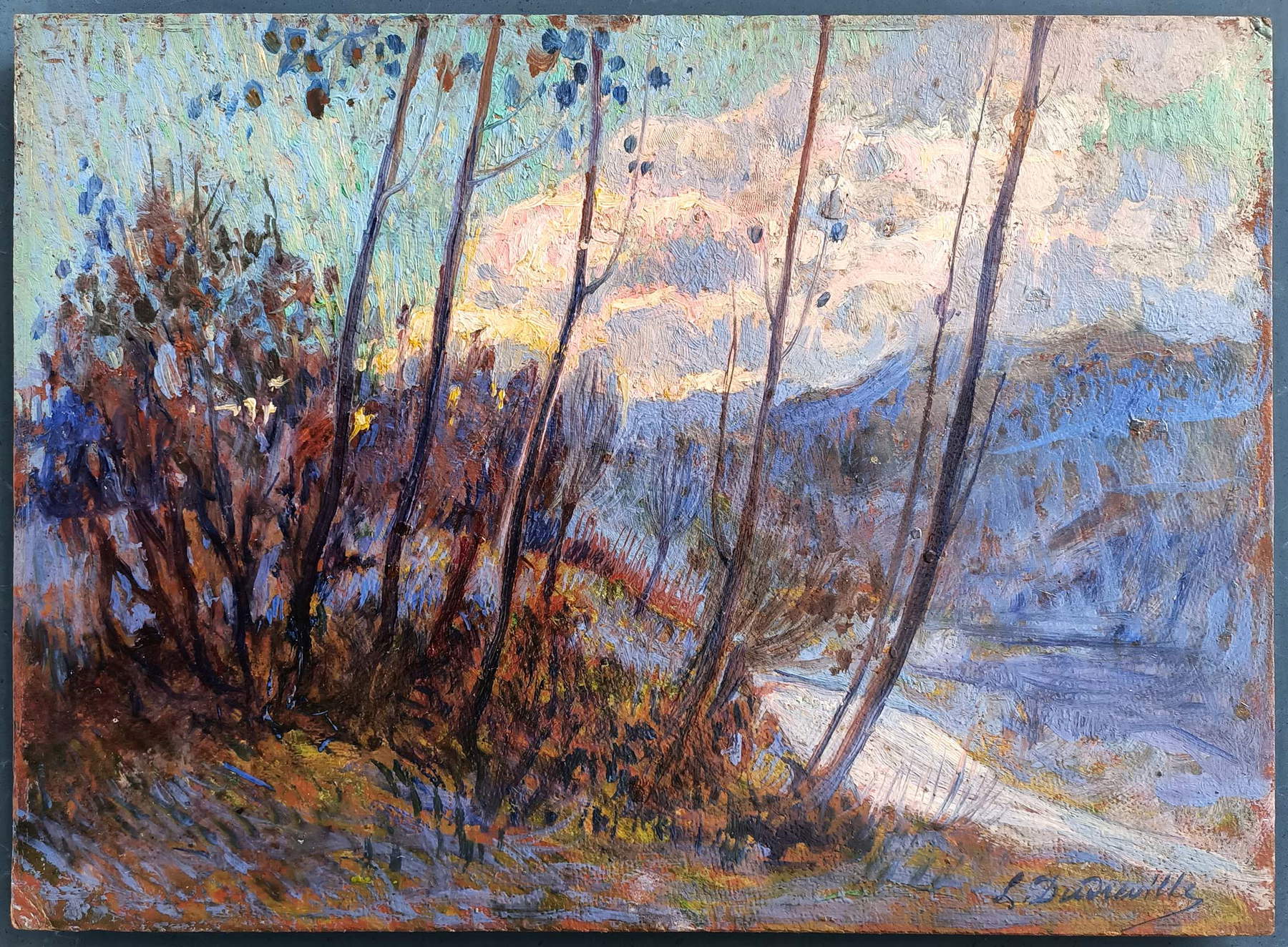

We begin by getting to know the artist, in the introductory section, with portraits of a couple of colleagues (Gino Severini and Anselmo Bucci) that faithfully restore not only Leonardo Dudreville’s handsome appearance (despite the fact that he had lost his right eye: which is why Gino Severini portrays him covering his face with his hands, and for this reason one will hardly see a portrait of Dudreville in which one can see his maimed eye well), but even his haughty temperament and interests: Gino Severini’s portrait is entitled Listening to Music, and the relationship with music is also functional in introducing the first room of the exhibition, dedicated to the Divisionist Dudreville, that of the first phase, with works ranging from 1905 to the early 1910s. The beginning is in the sign of a Divisionism of close Segantinian descent, as Spring in Valsassina, Roman Landscape or Morning on the Apennines attest: placid mountain visions where the brushstroke divided into thin strokes that blend, however, with broader and denser brushstrokes (with the result that Segantini’s analytical painting is interpreted in a much more leesy way) recall the lesson of the great painter from Trentino. Also reminiscent of Segantini’s art is the almost mystical approach with which Dudreville approaches the landscape, an approach evident especially in Primavera in Valsassina, where the fusion of human beings and nature goes so far that the sparse houses clinging to the mountainside blend into the landscape and almost seem like rock walls. The three works painted in Borgotaro, namely Borgotaro, Meriggio a Borg otaro and Inverno a Borgotaro (the artist will recall the cold he endured in the mountains to paint these two pictures in his memoirs, which also reveal singular qualities as a writer on Dudreville’s part, which is why they often appear very fictional and therefore unreliable, but very tasty reading) mark an early break from the strictest segantinian observance, in favor of more fluid and relaxed modes that will lead to some works such as the Sottobosco (unpublished), the Lucciole and the Trilogia campestre, in which the artist’s synaesthetic research is accentuated.

Particularly emblematic is the Countryside Trilogy, of which the Fair and The Voices of Silence are exhibited, respectively the view from above of a rural fair and an intense, evocative country night illuminated by the bioluminescence of a swarm of fireflies that punctuates, with its golden glow, a field on which stands a solitary tree. The central theme of the triptych, Francesco Parisi writes, echoing Elena Pontiggia, is music, “a kind of score that acts as a background, from the nocturnal murmur to the rustling of tree leaves, to the liturgical ringing of bells”: the “sound inspiration” came to Dudreville from his knowledge of painting that looked to symbolism, evidence that even in his early days Dudreville was questioning how to extend the limits of his own art. Precisely in this research that led Dudreville to execute paintings so capable of arousing auditory sensations, in this attempt to render sound by means of color, one must find, Parisi points out, “the viaticum to a deeper insertion of the artist into an avant-garde context that was favoring openness toward this new mode of expression.” One can thus guess at one of the reasons that led Dudreville to approach the Futurists, since the Futurists in the same years were experimenting with research somewhere between art and music (the Manifesto of the Futurist Musicians is from 1910).

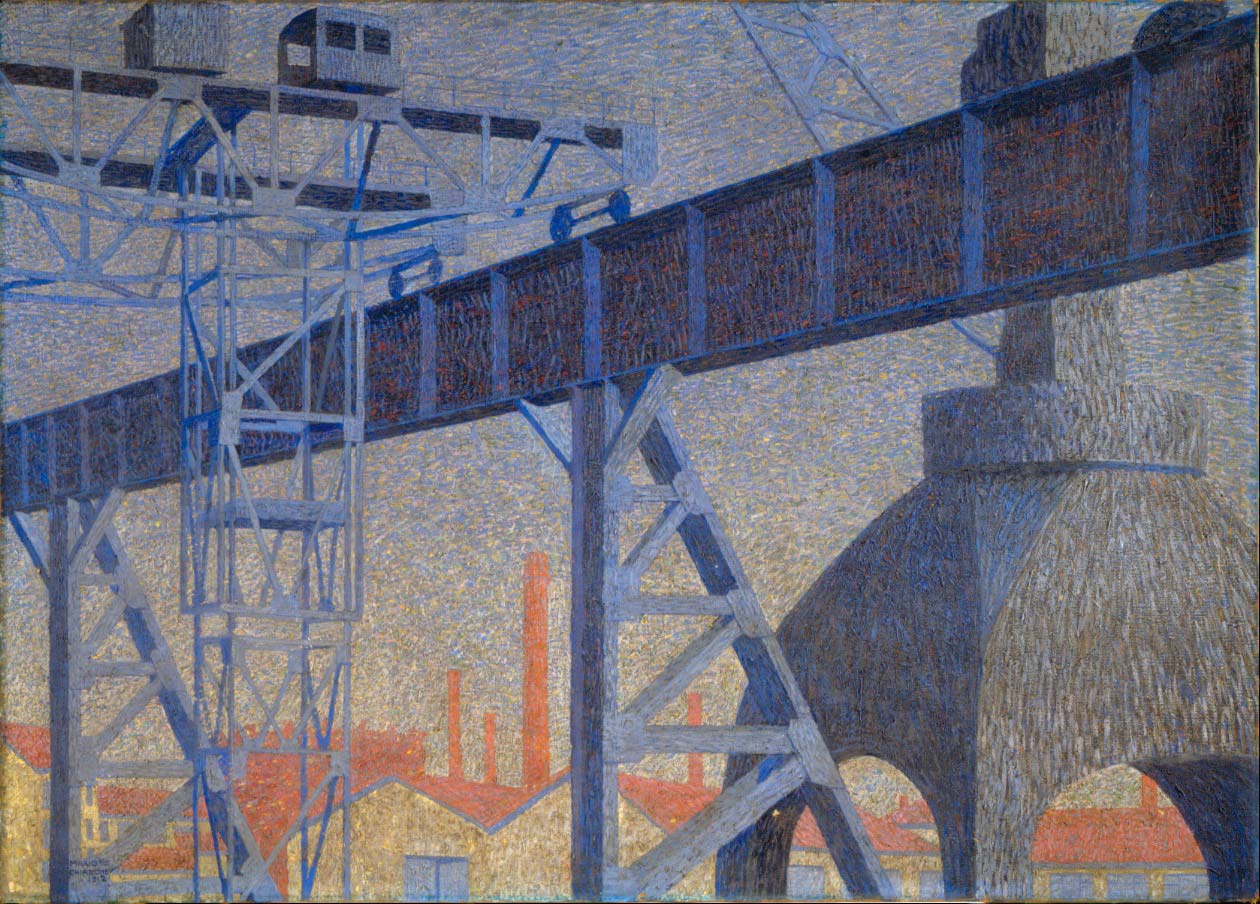

One then encounters a watershed section, the one devoted to the exhibition of the Rifiutati at the Caffè Cova in Milan, organized in 1912 by a group of artists whose works had not been by the commission of the Brera Biennial of the same year (it is estimated that more than half of what was notified to the commission had to undergo rejection by the latter). For the first time, an exhibition reconstructs the event to which is assigned no secondary importance, since the thesis of the show is that the exhibition of the refusés braidensi constituted on the one hand an occasion to bring together and compact the entire Milanese avant-garde, and on the other hand the basis for the birth of the Nuove Tendenze group animated by Dudreville. The paintings selected for the Lucca exhibition, despite its small number (there are eight), constitute a decidedly eloquent nucleus to make clear the main limitation of that review, namely the fact that it spoke too many different languages. Thus we go from Mario Chiattone’s Electric Crane, which approaches futurism (especially in its interest in the urban subject) but still looks to tradition, to Siro Penagini’s Nude with Masks, which instead turns its gaze to the France of CéFangs and Gauguin, and then again from the pointillism of an Aroldo Bonzagni interested in modern life with his London in the Rain (where, moreover, in the male figure, Dudreville himself was suggested to be recognized) to the secessionist instances of Guido Cadorin and Achille Funi. The exhibition presented itself with incendiary intentions, although a large part of the Rifiutati had already exhibited at Brera in the past, and the protest lacked a precise direction: Niccolò D’Agati, who in the catalog of Leonardo Dudreville e Nuove Tendenze has reconstructed the history of the Caffè Cova exhibition with dozens of details, writes that “it was an exhibition incapable [....] to give itself a defined physiognomy not only in linguistic terms [...] but on a structural level: it lacked a program and a real need for the exhibition.” Thus, "outside of a posed futurist boil, the avant-garde of the Rifiutati was the avant-garde that exhibited every year at the Brera competitions." It seemed, even to several critics who reviewed the exhibition, to be more the piqued response of a motley collection of artists who wanted their own recognition in an official exhibition, than the beginning of a true alternative experience. It was from this humus, however, that the nascent experience of Nuove Tendenze drew its sap.

Leonardo Dudreville,

Leonardo Dudreville,

To get there respecting the chronological iteration, it is necessary to follow a somewhat circuitous route, given the material of the exhibition and given the conformation of the exhibition spaces of the Ragghianti Foundation: one skips the next room (which houses the concluding section: we will return to it later) and reaches the mezzanine, where the chapter of the exhibition dedicated to the birth (and the end, given its very short duration) of the Nuove Tendenze group is welcomed. It had been formed on the initiative of Dudreville and the aforementioned Ugo Nebbia, an art critic, in 1913: it was an extremely composite group, heterogeneous in expressive means and above all in languages, arising essentially from a Futurist substratum and then open to welcoming personalities also coming from completely different experiences. The program itself, drafted by Ugo Nebbia, had a very open character: “Intends the group Nuove Tendenze,” it read, “above all to give a way to affirm itself and to come into direct contact with the public to those expressions of art, which, because of their character of advanced research can hardly make themselves known and appreciated in their proper value, in the usual exhibitions.” He added, explicitly, “No determinate formula is imposed: all those who, in their work feel that they have seriously expressed, or attempt to express, a modern and original personal vision, will be well received.” The group’s first (and last) exhibition opened in Milan on May 20, 1914, and would receive a rather cold reception from critics. The life of Nuove Tendenze was short-lived: the ephemeral eexperience could already be said to have ended after that first exhibition.

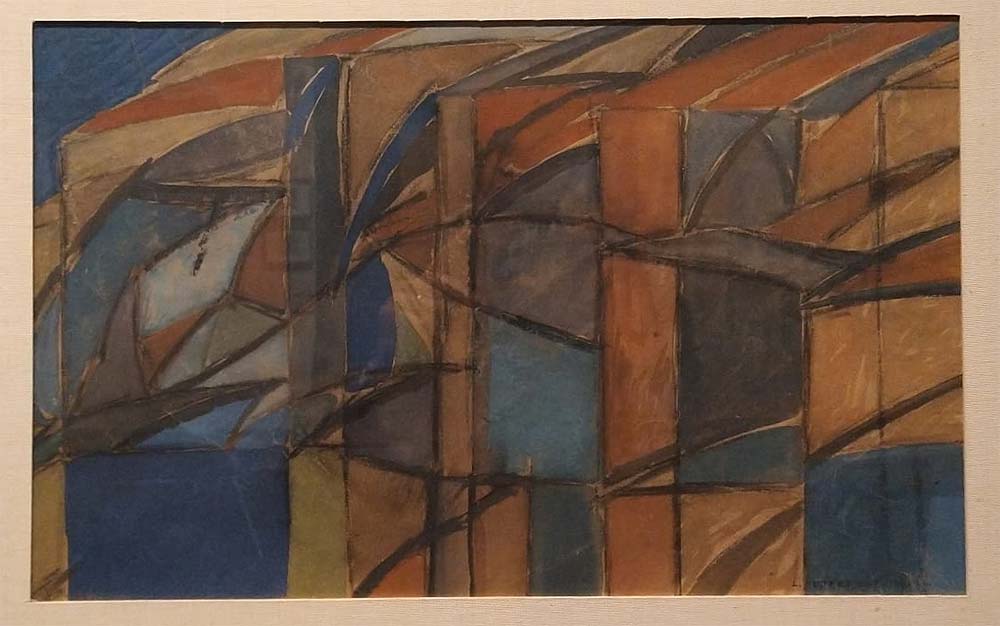

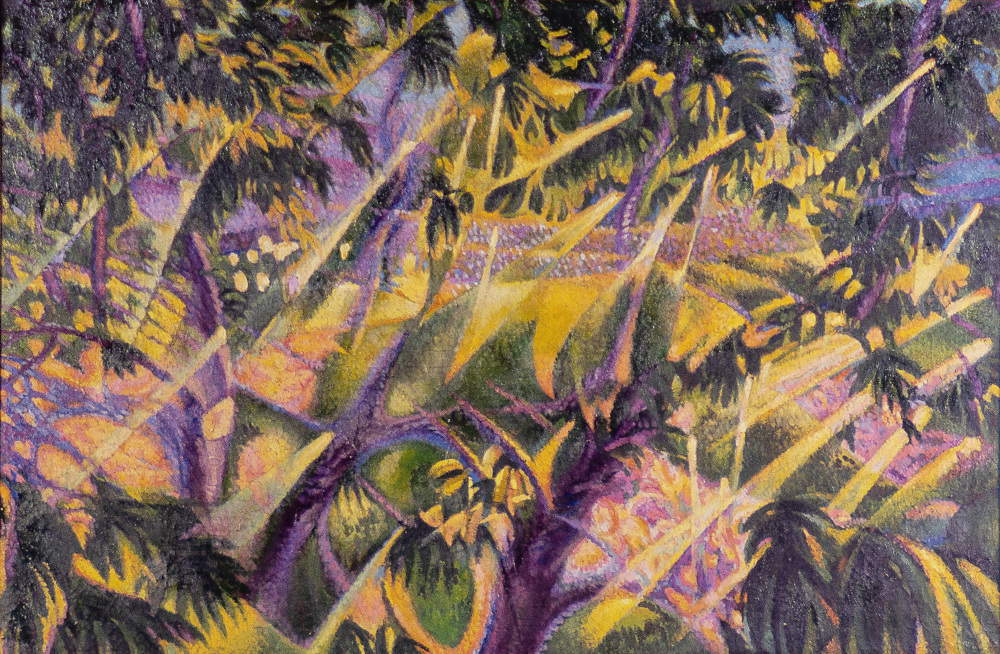

In Lucca, the room devoted to the New Tendencies exhibition brings together a careful selection of everything the group had proposed, including painting, sculpture, and architecture. Dudreville exhibited the Four Seasons (Autumn is in the show), a cycle that stands out, writes Agnese Sferrazza in the catalog entry, for the “absolute balance with which Dudreville manages to blend and use realistic elements of everyday life (the flowers blooming, the wheat and cloths hung out to dry in the wind, the cloudy sky over the city, the grayness of the bare trees in the crowded boulevard) with an essentially abstract compositional structure supported by the coloristic choices that are totally consistent and paradigmatic of the subject depicted.” Dudreville proved to be an up-to-date and research-driven painter, and he had won acclaim for the innovative and radical way in which he approached a traditional subject (as opposed to the Futurists who favored themes of modernity instead), and he further demonstrated this even with totally abstract paintings, the “rhythms” (on display were the Ritmi emanating from Ugo Nebbia and the Ritmi emanating from Antonio Sant’Elia), with which he expressed in the form of lines, shapes and colors the psychological feelings that his friends aroused in him, based on the intention of wanting to translate a feeling into a “multiple power of form, color, depth,” to use the artist’s own words.

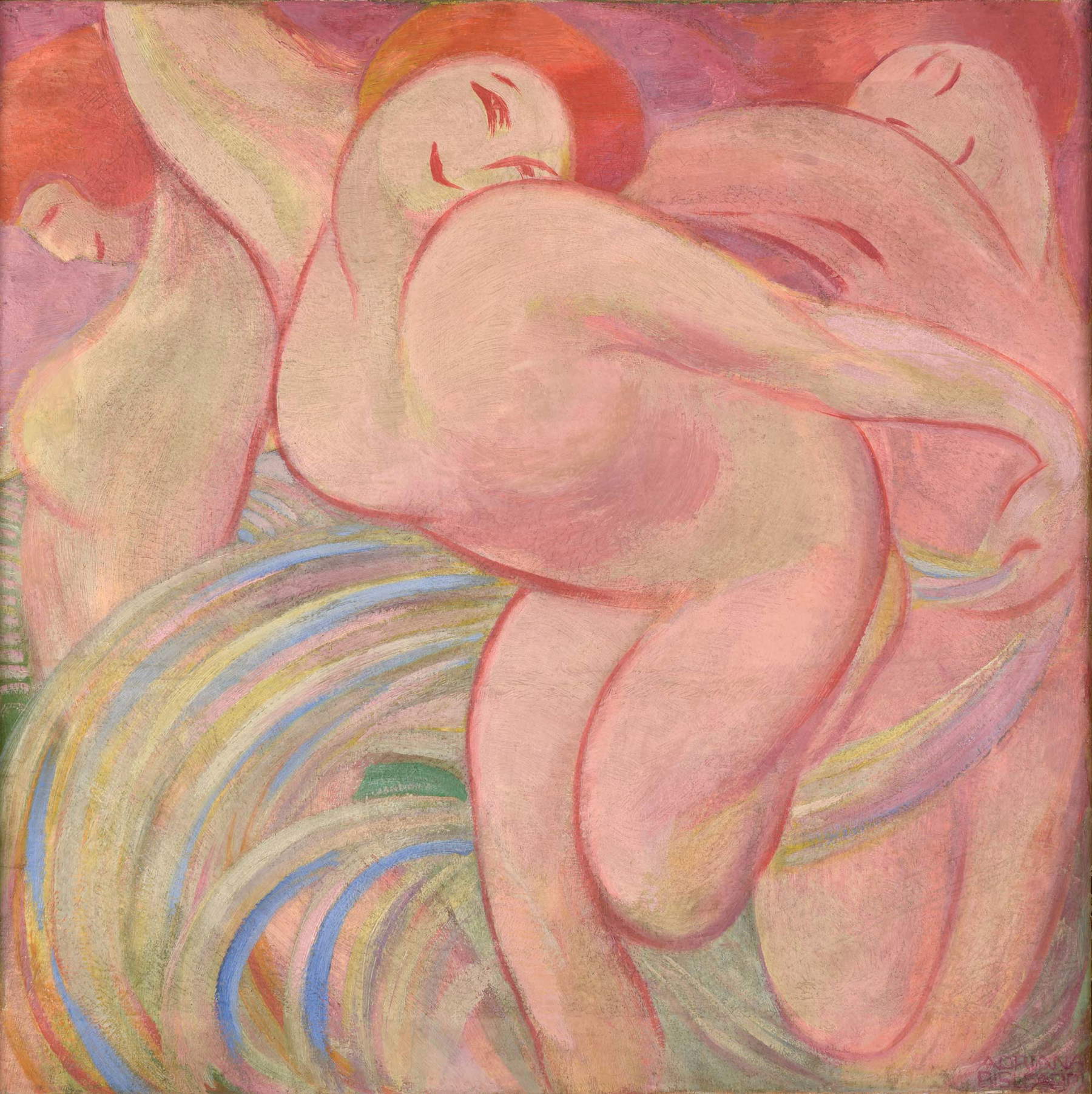

Other artists who had exhibited at the Nuove Tendenze show include Achille Funi, who was present with his Uomo che scende dal streetcar, a work that marks the highest point of tangency with futurism by an artist who would have little to do with the avant-garde of Boccioni and colleagues (although this same painting cannot be considered a fully futurist work, writes Maria Letizia Paiato, “because of its tendency toward solidity and rhythm of volumes”), and again Adriana Bisi Fabbri, the only woman in the group, who at the exhibition of the Nuove Tendenze group presented herself with La danza (The Dance), which looked instead to French painting, demonstrating a certain knowledge of the Fauves, of whom, however, she proposed a more graceful interpretation. And then Carlo Erba again: the nine works he brought to the Nuove Tendenze exhibition are now dispersed, but the Fondazione Ragghianti’s exhibition makes up for this with Le trottole del sobborgo (which go), a very special study of movement tinged with expressionist suggestions. Architecture is represented by folios by Giulio Ulisse Arata and Antonio Sant’Elia, while the only sculpture in Lucca is Vecia Marinela by the Venetian Giovanni Possamai, which declines Lombard verism according to French and Secessionist suggestions.

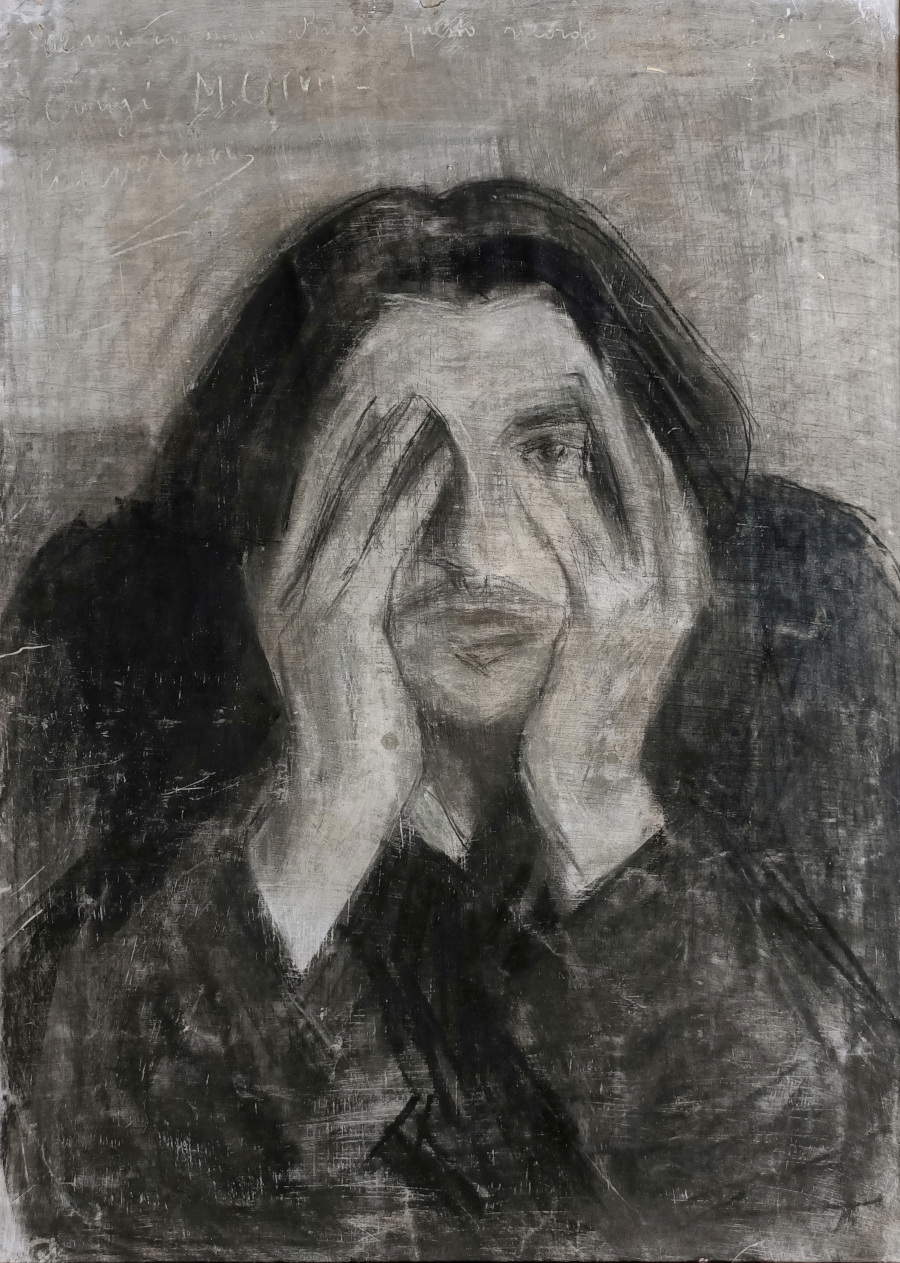

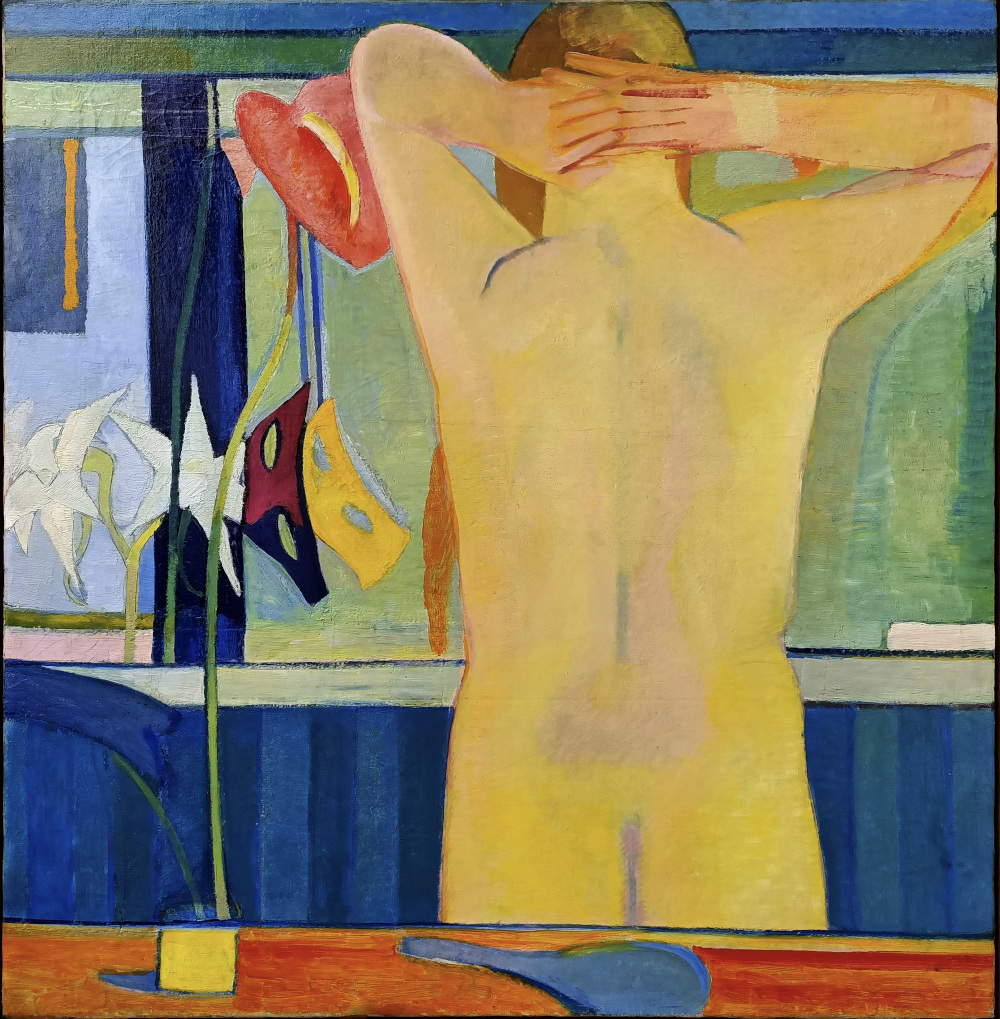

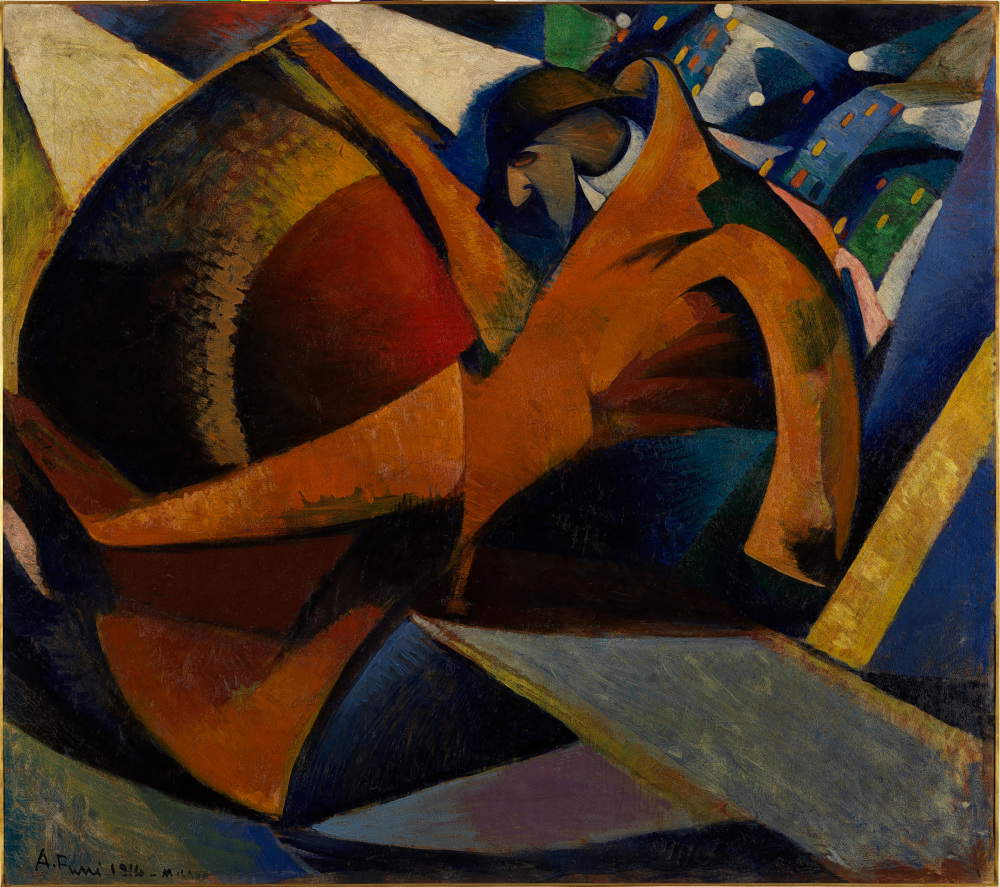

Not even the Novotendents were able to give themselves an identity, to find a common project, to continue beyond the perhaps somewhat too ecumenical proclamations of the manifesto, to give an aesthetic organization to the group, with the result that each would then go their own way. Dudreville, who although he disbanded the group continued for some time to use its name in some publications, at first smoothed out the more radical points of his abstractionism, returning to a more mediated art, demonstrated by the 1914 Lyric of Sunset, a painting in which a country landscape at dusk is rigorously divided into two distinctly separate and different registers: a synthetic painting in the lower part, to describe trees and houses, and conversely a decomposition of shapes and colors to study, in the upper register, the sunset light, according to a diagonal line pattern typical of futurism, employed to convey a sense of poetry, as the title suggests. One experiences similar sensations when looking at Aspiration, on loan from the Mart in Rovereto, one of Dudreville’s most famous paintings, who is said to have executed it to express “man’s instinctive need to ascend and to perfect himself, to take his own self to higher and better spheres.” Dudreville’s yearning to ascend is embodied in a web of intersecting lines, a dazzling upward motion that rises above a somber score: the forms of the lower portion of the painting are meant to recall the chaotic atmosphere of a city, a symbol of material life, while the blades of light that start from a bright red center, signifying a beating heart, rise upward in increasingly pure colors to become a kind of column that ideally continues beyond the limits of the painting.

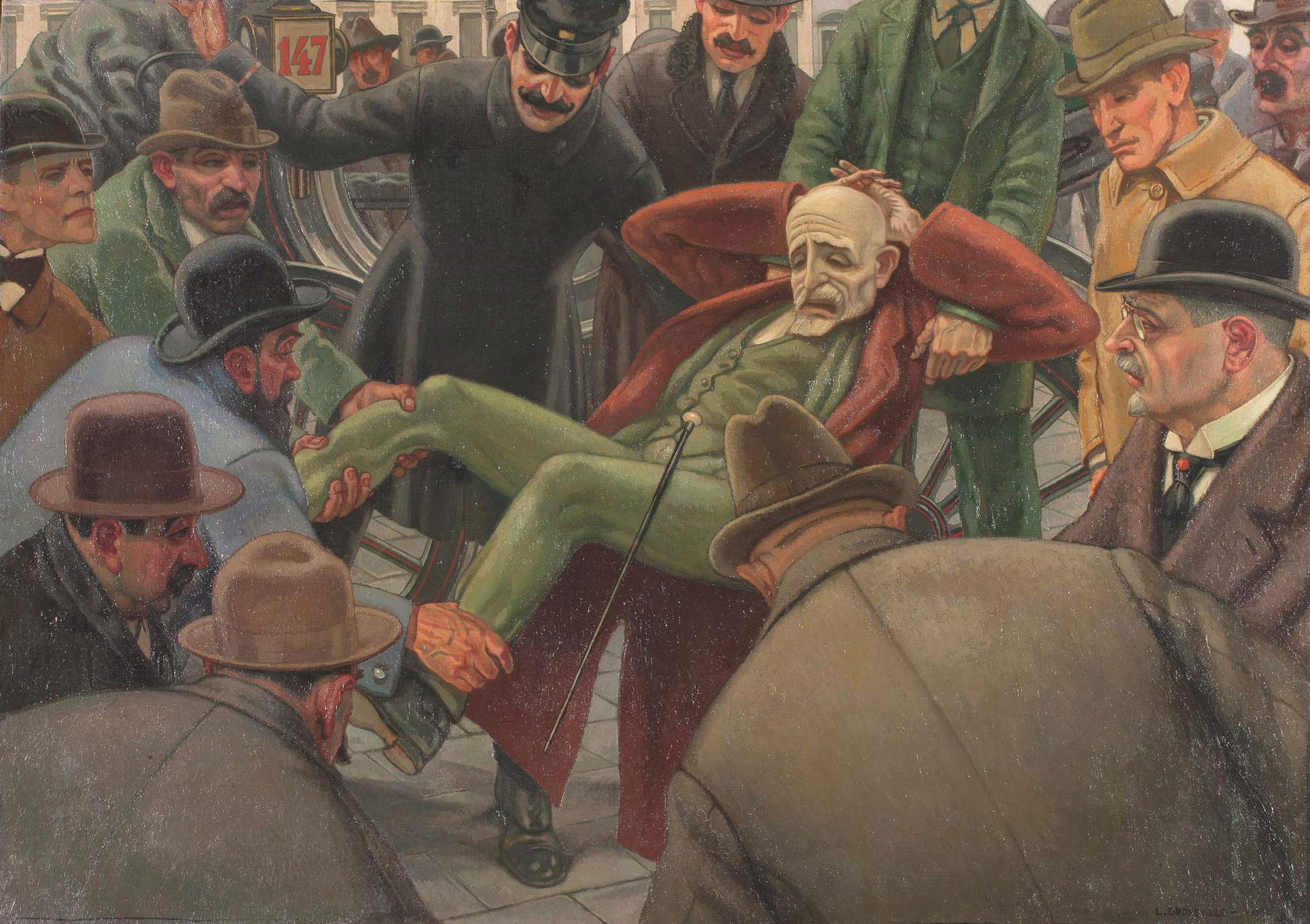

Aspiration represents the apex of Dudreville’s research on states of mind and, more generally, on the expression of interiority by means of painting: later, the Venetian artist would devote himself almost exclusively to the representation of exterior phenomena, from the landscape of Nel bosco di castagni completed in 1918 (the study for the painting, unpublished, was published as part of the Ragghianti Foundation exhibition), which, however does not shy away from suggesting the idea that even natural phenomena have a rhythm, all the way to a painting like Senso, a female nude that, while presenting itself with typically Futurist decompositions, returned to a look at symbolism (see the way the blond hair of the protagonist is painted) and above all directed toward the objective reality that would soon be Dudreville’s only orientation. Senso was moreover exhibited at the Great Futurist Naziaonale Exposition of 1919, where it was admired and appreciated by Gabriele d’Annunzio. The exhibition closes with Il caduto (The Fallen ) of 1919, a work on loan from the Museo del Novecento in Milan, which depicts an episode recounted in great detail by Dudreville himself in his memoirs: the fall of an elderly man, rescued by passersby, in the center of Milan. The “skinny, petite old man, and horribly cadaverous in the face,” as Dudreville would have described him, depicted in a painting at once grotesque and tragic, which probably betrays knowledge of the experiments being conducted at the time in Germany where the Neue Sachlichkeit was to emerge, marks the turning point toward “realism” in Dudreville’s art, and the point of arrival of the Lucca exhibition.

It is, moreover, precisely The Fall en in which Dudreville himself recognized his own turning point: in his memoirs he would have described it as rather abrupt, starting from the very event that had inspired the painting, but in reality we know it was decidedly more meditated and less instinctive than it appears from reading the text, despite the fact that The Fallen can be considered a manifesto of this total and radical paradigm shift. “Already in previous years,” recalls Elena Pontiggia, who in her catalog essay focuses precisely on the reasons for this turn, “the artist had oscillated between the decomposition of form and the progressive emergence, in those decompositions, of fragments of figures and things left intact.” Senso is one of the works best suited to understand the emergence in nuce of this “new” Dudreville. Realism thus stands as an “expressive metamorphosis that does not arise from a revolution, but from the evolution of instances also present in the artist’s earlier works”: even in his avant-garde research, he had hardly renounced elements drawn from tradition.

The exhibition is therefore exemplary in bringing out a complex figure with an extremely varied path who was Leonardo Dudreville. But the Fondazione Ragghianti’s review intervenes not only on the artist, who emerges as a figure who is anything but secondary in the panorama of the arts of the 1910s, to the detriment of the fact that his name is still little known to the general public: the exhibition also sheds light on the extent of the contribution that the Nuove Tendenze group managed to make to the art of those years. Far from being not only exalted, but also from being placed in a historiographical space that would not suit it, the experience of Nuove Tendenze is presented to the public with all its limitations, first and foremost “the intrinsic weakness of an avant-garde lacking the capacity to compact itself around a common project,” as D’Agati writes in his contribution, but also as an attempt, however unrealistic, to propose itself as an alternative, as well as a moment of embryonic development of aesthetic lines that would later result in the same Novecento instances, as Alessandro Botta notes. Nor should we forget the “promotional” role, if you will pardon the term, that the group attributed to the figure of the art critic (so much so that the same group, compared to six artists who subscribed to the first official communiqué, published in 1913, included as many as four critics, or “publicists,” as they curiously called themselves): Decio Buffoni himself, one of the four, published an enthusiastic review in the newspaper La Perseveranza the day after its opening. Perhaps it is anachronistic to see in the critics of New Tendencies forerunners of today’s curators who scramble to promote initiatives often of dubious efficacy and dubious interest, but with a certain irony one will be able to see original similarities. Beyond the facetiousness, the critical and historiographical collocation of that experience is rendered by the exhibition in an extremely rigorous manner: one will therefore leave the Fondazione Ragghianti certain of having visited an exhibition of great depth, supported by a full-bodied catalog, which has the style of a monograph (reproductions of several paintings not included in the exhibition are also included), full of novelties and ideas for further study.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.