by Federico Giannini (Instagram: @federicogiannini1), published on 31/12/2019

Categories:

Exhibition reviews

/ Disclaimer

Review of the exhibition "Japonism. Winds of the Orient in European Art 1860-1915," in Rovigo, Palazzo Roverella, through Jan. 26, 2020.

It was the French artist Philippe Burty (Paris, 1830 - 1890) who was the first to coin, in 1872, a term later destined to identify that mania for Japan which, for at least two decades to that part, had taken possession of many painters, sculptors, literati, decorators and architects throughout Europe: Japonisme was the noun Burty invented to bring together, under a single title, a series of articles published in different issues of the journal La Renaissance littéraire et artistique, in which their author, from time to time, offered readers a quick review of things Japanese: works of art, language, books, philosophy. Recent, on the other hand, is the meaning of “Japonisme” to which we are accustomed, and by which we are accustomed to designate that interest which the European artists of the time manifested in Japanese art and which ended up modifying, directing and often even subverting the traditional canons of composition, which triggered small revolutions on the level of iconography, which stimulated the study of Oriental techniques. An interest whose origins are difficult to trace with certainty, not least because it experienced varied channels of dissemination, poured over the continent like an entirely spontaneous wave, was declined in different forms according to the aims of those who approached it. Just by way of example, it is curious to note that what is perhaps the first historically attested expression of interest in Japan on the part of an Italian artist, represents a completely marginal and almost forgotten episode, and features as its protagonist a painter unknown to most, the Neapolitan Bernardo Celentano (Naples, 1835 - Rome, 1863), who in 1857 painted a canvas for the Jesuits in Dublin, the subject of which was St. Francis Xavier preaching to the Japanese. Since Celentano was a realist painter, he had taken care to ensure that his Japanese were as credible as possible: the artist therefore took to studying imported fabrics closely, documenting himself in books and travel diaries, and carefully observing the illustrations he had managed to obtain. And all this when sakoku, Japan’s centuries-old, traditional isolation from the rest of the world, had just ended: the result was that Celentano, as he wrote in one of his letters, took there “so much passion, that I am always working and dreaming of Japanese and I am so much aware of their type that I feel I have been to Japan.”

Of course, Celentano’s “passion” went no further, and of course he did not have to go into depth, since it was rather a momentary and superficial fervor, incapable of arousing any sort of following. However, this surface curiosity was the way in which Japanese art was at first received in Europe: and if at first it was an episodic phenomenon, soon the taste for Japan turned into a bourgeois fashion that infected artists and collectors, and finally became a cultured vague, capable of grafting itself onto European art by making substantial and profound changes. This is the parabola described by the exhibition Japonism. Venti d’Oriente nell’arte europea 1860-1915, which in the rooms of Palazzo Roverella, in Rovigo, traces an interesting overview of a crucial moment for the arts in the Old Continent, through an itinerary that the curator, Francesco Parisi, has conceived divided by countries. The exhibition comes after those that, again Palazzo Roverella, dedicated to the European secessions (in 2017) and to the relationship between art and magic (in 2018), to close a trilogy through which Parisi has with merit explored fashions, motifs, themes, transformations, and suggestions capable of animating art in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, always with scientific rigor and high-level popular projects, with an approach aimed at looking at all forms of art (this year’s exhibition alone counts paintings, sculptures, graphics, decorative arts, textiles, books, posters, furniture), and ensuring a significant role for engravings (Parisi is one of the most highly regarded contemporary engravers). Reconnaissance, given the vastness of the subject matter, is done from a bird’s eye view, and always with a focus on the history of art, rather than on the history of taste or the history of collecting, areas that the exhibition touches on marginally, preferring to concentrate on the more incisive and lasting implications of Japanism.

|

| Exhibition Hall Japonism. Winds of the Orient in European Art 1860 - 1915 |

|

| Exhibition hall Japonism. Winds of the Orient in European Art 1860 - 1915 |

|

| Exhibition Hall Japonism. Winds of the Orient in European Art 1860 - 1915 |

|

| Exhibition Hall Japonism. Winds of the Orient in European Art 1860 - 1915 |

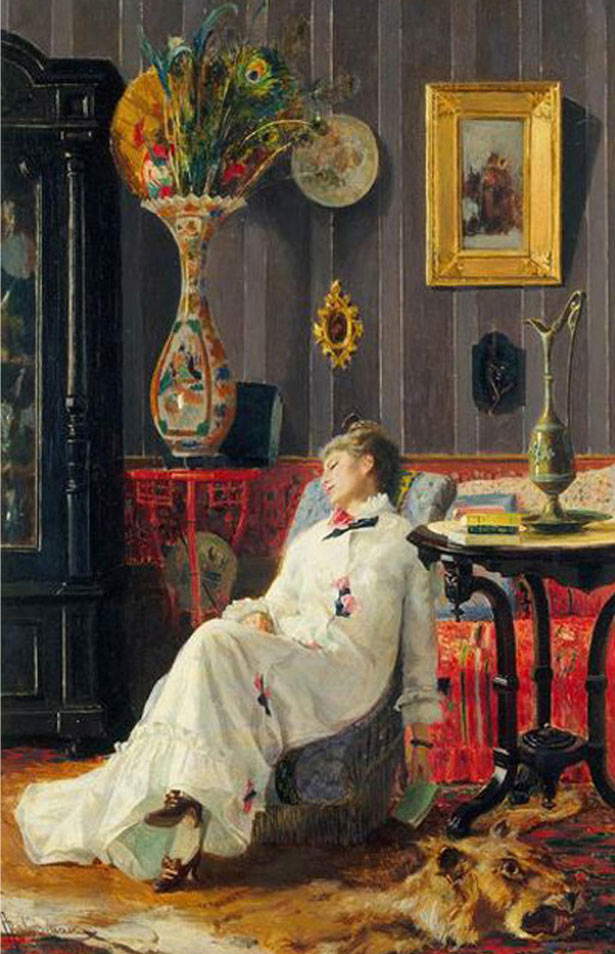

By clarifying the differences between japonisme and japonaiserie (the former has already been mentioned: by the latter term is meant a more generic attraction to Japanese art, which does not, however, transcend the contingencies of fashion or pure aesthetics), the beginning ofthe exhibition offers the public a first roundup of works by Italian artists who approached Japan by not going beyond the mere resumption of decorative motifs or the insertion of some oriental element to give an exotic touch to the painting. Responding to needs of this kind were works in which models were dressed in kimonos or oriental fabrics, or where prints, ceramics, and handicraft objects that à la page collectors bought in specialized shops appeared. It was the age of eclectic taste, the time when one entered the home of a George Washington Wurts, a Frederick Stibbert or a Harold Acton and was overwhelmed by a congeries of medieval gold grounds, Renaissance wedding chests, seventeenth-century canvases, Tyrolean altarpieces, Chinese porcelain, Flemish tapestries, Byzantine ivories, Russian icons, and assorted Japanese objects: screens, fans, plates, pottery, netsuke, kakemono that collectors bought either directly on site if they were fortunate enough to travel to Japan, or in the many stores that began to trade in japoniserie (one of these was that of “Signora Beretta on Via Condotti” mentioned by D’Annunzio in his articles for La Tribuna: and the poet’s writings still remain a privileged source for getting an idea of the frivolous, light and disengaged taste for japoniserie that, in Italy, had spread especially following the arrival in Rome in 1873 of the Iwakura mission). Works that well embody this taste, and which visitors encounter as a prologue, are, among others, the Moment of Rest by the Tuscan Adolfo Belimbau (Cairo, 1845 - Florence, 1938), which captures a bourgeois interior where a large Japanese vase stands out, and the refined Bice. Iridescences of Mother-of-Pearl, with which Filadelfo Simi (Levigliani, 1849 - Florence, 1923) participated in the first Venice Biennale in 1895, and where the painter’s niece, Bice Beani, is adorned with precious fabrics and an oriental fan, in a painting with a strongly horizontal cut, like the one that characterized the emakimono, a sign that perhaps Simi’s (an artist, moreover, still much underestimated today) research went beyond the facade shots of many of his colleagues. Also noteworthy is Antonio Fontanesi ’sEntrance to a Temple in Japan (Reggio Emilia, 1818 - Turin, 1882), a reminder of the Reggio Emilia artist’s trip to Tokyo, where he was called to teach at the K?bu bijutsu gakk?, the state school of fine arts founded in the capital in 1876 with the intention of modernizing the country’s art in a modern sense, bringing it up to date with the achievements of Western art (the institute’s events are reconstructed in detail, in the catalog, by a fine essay by Mario Finazzi).

The real journey into Japanism, however, begins with the section devoted to France and Belgium, countries that first responded to the incoming solicitations from the Far East. Here, Claude Monet (Paris, 1840 Giverny, 1926) was not only among the forerunners of Japonisme, but even wanted to attribute a sort of primacy to himself, claiming to have purchased his first Japanese print when he was only sixteen years old. Anecdotes aside, the father ofImpressionism is credited with some of the earliest experiments in Japonisme: his Passerelle à Zaandam, with that vertical cut further punctuated by the tree in the center and with the bridge slanting in, already reveals premature debts to Hiroshige’s ukiyo-e, available in large quantities in 1970s Paris. But that’s not all: Japanese prints were also copiously available in Antwerp, and it was in the Belgian port that Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890) began to become acquainted with them, to the point of creating his own collection (Japanese prints had very low costs). Of Japanese art, van Gogh admired the ease, immediacy, light, “extreme clarity” of those works “as simple as a breath,” as he would write in a letter to his brother Theo. And he admired their radiant light and strong colors, to the point of longing for a move to a place that could communicate to him those same sensations that the art of Japan had granted him: sensations that the Dutch artist sought to encounter in the Midi, where he painted Oliviers à Montmajour, his only work exhibited in Rovigo. It is a paper on which ink draws olive trees (which in reality, wanting to stick to botanical exactitude, would be Aleppo pines) trying to imitate that rapidity of stroke with which Japanese artists created their figures and which van Gogh had declared he envied them. And if van Gogh was interested in the brightness and directness of the Japanese, his friend Paul Gauguin (Paris, 1848 - Atuona, 1903) was fascinated by full colorism and unconventional (at least for a European) perspective cuts, as he was able to demonstrate in Fête Gloanec, a still life executed in 1888 for the birthday of Marie-Jeanne Gloanec, the innkeeper at whose boarding house the Parisian painter used to spend his stays in Pont-Aven.

It is theImpressionists who are credited with evolving Japanism, raising it to a higher plane than the amused exoticism of the realist painters, and it was Edmond de Goncourt who facilitated the process (although his approach to Japan was not unlike that of the eclectic collectors), since he was at the center of a network of relationships involving merchants, collectors, artists, and men of letters. And if the Impressionists approached Japan as early as the 1960s (while remaining at the level of mere citation), beginning to reflect with greater substance from the following decade, it was with the 1980s that Japanism spread, partly because of a greater awareness, partly because of the role exerted by the Universal Expositions and a constant and growing openness of Japan to the West, and partly because phenomena of derivative Japonisme began to be activated, since for certain artists the source was often not Japanese works, but works by fellow countrymen who elaborated on the cues coming from the Rising Sun (Degas above all). Among those most attracted to the Japoniste taste was Paul Ranson (Limoges, 1861 Paris, 1909), who would be jokingly dubbed by other Nabis “the most Japanist Nabi.” the many recurring themes of Japanese art (animals, courtesans, waves) are reworked by Ranson into a production with chronologically distinct strands by Marc Olivier Ranson Bitker in the essay devoted precisely to Ranson in the catalog (a pencil and charcoal drawing on paper, Danseuse à l’eventail, is outlined with the same readiness that animated Japanese prints, but is resolved into more sinuous lines, which precursorart nouveau: moreover, the use of a very marked outline is inferred from Japanese art). Japan also inspired the production of objects of oriental taste, such as fans (“for many Impressionists and Post-Impressionists,” writes Tobias Kämpf in the catalog, “the fan became a paradigm of their aesthetic work, emphasizing their orientation toward Far Eastern cultures in general and Japan in particular”) and screens: of the former, numerous examples are on display in the exhibition, including a landscape at sunset by a young Paul Signac (Paris, 1863 - 1935), who in 1890 visited an exhibition of Japanese art at the Academy of Fine Arts in Paris and was unfailingly surprised, while the latter includes the Promenade des nourrices by Pierre Bonnard (Fontenay-aux-Roses, 1867 - Le Cannet, 1947), another prominent name of the japonisants. It is also beyond interesting to observe how Japonisme is declined by the Symbolist painters (above all, those of the Rose+Croix group, for a compelling reference to the 2018 exhibition on art and magic): for them, writes Jean-David Jumeau-Lafond in the catalog, Japanese art provides, “beyond pure formal play” and “beyond its spiritual substratum,” an exotic dimension functional to “evoke mystery, estrangement and surprise so as to give voice to their inner visions.” And it is an inner vision that Alexandre Séon (Chazelles-sur-Lyon, 1855 - Paris, 1917), one of the most active exponents of the Rose+Croix, gives form to in the previously unseen pair of oil on panel La mer - Rochers dans la mer and La mer. �?le de Bréhat. Soir calme, where the rendering of the landscape reflects a knowledge of oriental art reread above all by virtue of its immaterial values. The exhibition assigns a non-secondary role to the prints of Henri Rivière (Paris, 1864 - Sucy-en-Brie, 1951), who of the French was perhaps the most faithful to Japanese styles and techniques: his landscapes (such as L’entrée du port de Ploumanac’h) combine sceneries of northern France with the aesthetics of Hokusai’s prints.

|

| Adolfo Belimbau, Moment of Rest (1872; oil on canvas, 34.6 x 22.3 cm; Florence, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Filadelfo Simi, Bice. Iridescences of Mother of Pearl (1895; oil on canvas, 60 x 178 cm; Florence, Galleria d’Arte Moderna di Palazzo Pitti) |

|

| Antonio Fontanesi, Entrance to a Temple in Japan (1878-1880; chiaroscuro preparation on canvas, 114 x 145 cm; Reggio Emilia, Musei Civici) |

|

| Claude Monet, Passerelle à Zaandam (1871; oil on canvas, 47 x 38 cm; Mâcon, Musée des Ursulines) |

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Oliviers à Montmajour (1888; ink on paper, 480 x 600 mm; Tournai, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

|

| Paul Gauguin, Fête Gloanec (1888; oil on panel, 36.5 x 52.5 cm; Orléans, Musée des Beaux-Arts) |

A theory of elegant vases by �?mile Gallé and other leading ceramists leads the public to the section of the Rovigo exhibition devoted to Germany, Austria and Bohemia, opened by Die Japanerin by Hans Makart (Salzburg, 1840 - Vienna, 1884), a kind of revisiting in an oriental key of the story of Cleopatra (the panel was conceived together with two other paintings depicting the suicide of the queen of Egypt): death, eros, and oriental fascination add up to a painting with strong theatrical and restless accents, where Japan is little more than a pretext. However, beyond this episode, which should probably be read as a reflection of the appeal exerted by Japan’s pavilion at the Weltausstellung held in Vienna in 1873, the reception of Japanese novelties in Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire was somewhat delayed, and this delay, Parisi speculates, can be explained by the “unwilling attitude to ’revolutions’ of the Viennese artists themselves.” the Viennese Secession did not have “its distinctive note in the rebellion and the forced search for novelty such that it laced itself without qualms with the substantially different principles that constituted the essence of Japanese art”: consequently, it was only at the end of the century that the latter’s models “became decisive for the stylistic modulation of Secessionist taste with their deconstruction of the traditional layout marked by the search for a new relationship between figure and environment and by new decorative formulas.” While Secessionist decorativism is well represented by a work such as Schwämme (“Mushrooms”), a fabric designed by Koloman Moser (Vienna, 1868 - 1918) and translated into cotton, wool and silk by the Johan Backhausen & Söhne manufactory, where the taste for phytomorphic patterns of oriental derivation touches one of its peaks, it is already a memory in the Sous-bois à Semmering by Carl Otto Czeschka (Vienna, 1878-Hamburg, 1960), who reduces the forests of the Austrian Alps to their essential elements with a taste that is already Art Deco and working through a technique that uses only two colors (green and black) to create contrasts with which the artist achieves an effect that makes his tempera look like an engraving. In Gustav Klimt (Vienna, 1862-1918), Japanese influences can be read between the lines, in the stylized forms, thick outlines and never-quenched sensuality, while the case of Emil Orlik (Prague, 1870-Berlin, 1932), the leader of the Bohemian Japonists, is different, a land particularly receptive to Japanese art in that, although it did not have strong relations with the East like those of other nations, it nurtured a desire to keep up (the result was a dense array of young artists capable of updating themselves, even with surprising results): Orlik was among the Europeans closest to the Japanese, and to better study the latter’s techniques he himself traveled to Japan (he was among the very rare artists who succeeded in the feat of going there in person): out of this synthesis came such works as the triptych of lithographs consisting of Der Maler, Der Holzschneider and Der Drucker (“The Painter,” “The Carver,” “The Printer”), with which Orlik manifests his interest not only in Oriental practices but also in the subjects he uses, or such as Landschaft mit dem Fuji im Hintergrund (“Landscape with Mount Fuji in the Distance”), inspired by a view dear to Japanese engravers, and realized with large, full backgrounds.

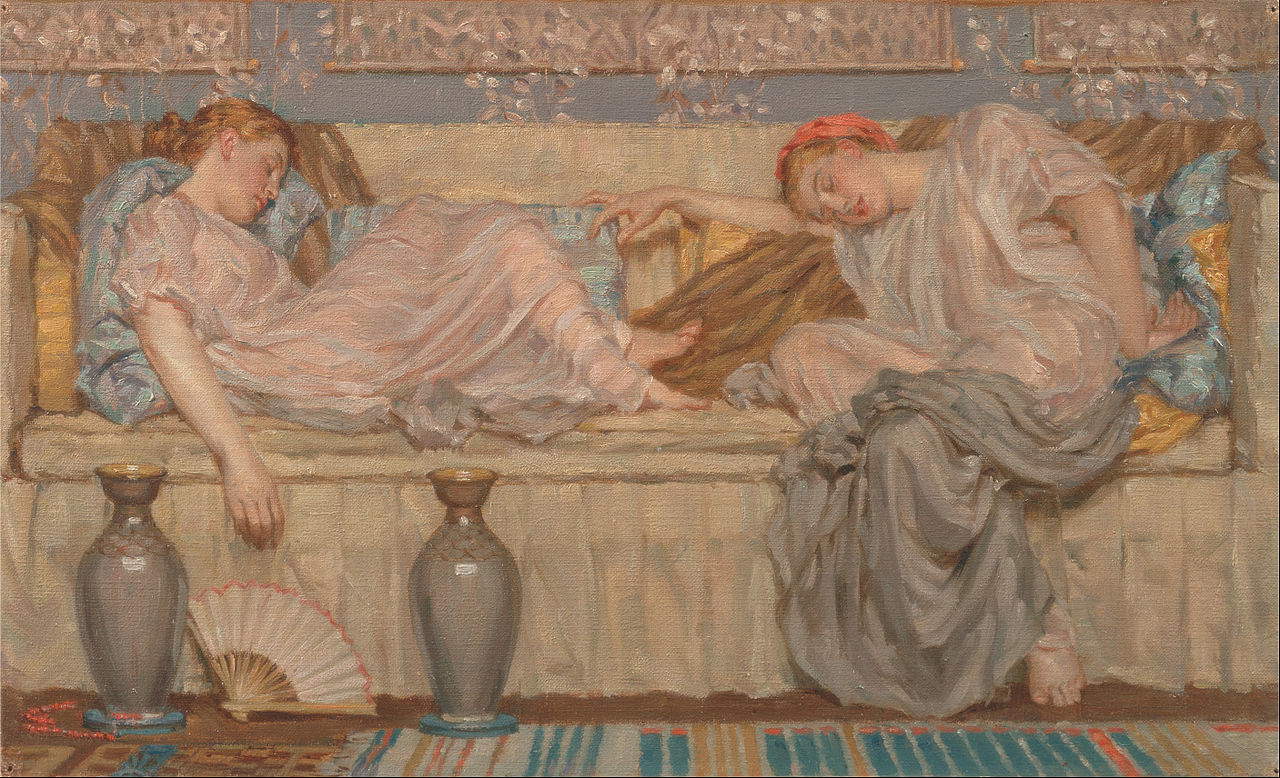

English Japonisme, to which the following section is devoted (along with a catalog essay by Manuel Carrera), also took root across the Channel thanks to the fertile humus from which Pre-Raphaelitism and the Aesthetic Movement sprouted: and since in England Japanese art was more congenial to the instances of the academy than to those of the avant-garde movements, the reverse occurred from what was happening in France. If, therefore, in the production of academic artists such as Albert Joseph Moore (York, 1841 - London, 1893) the Japanese element merges with the painter’s classical imagery in order to accentuate the imaginative narrative eccentricity of the scenes (look at how, in Beads, Ancient Greece and Japan manage to find a bizarre, unusual synthesis), one has to wait for a painter in contact with France such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler (Lowell, 1834 - London, 1903) to find one of the few artists active in the United Kingdom capable of grasping certain motifs of Japanese art at its depth: Carrera identifies the peculiar elements of Japanese Whistler in the flattened perspectives, the essential setting “often reduced to a monochrome background,” “the choice of having the figure occupy almost the entirety of the canvas,” and the idea of “centering the sense of the paintings on the harmonic agreement of two or more tones” (a work such as The Thames reveals an obvious closeness to the ukiyo-e prints of Hokusai and Hiroshige: in compositional cut, framing, iconographic choices).

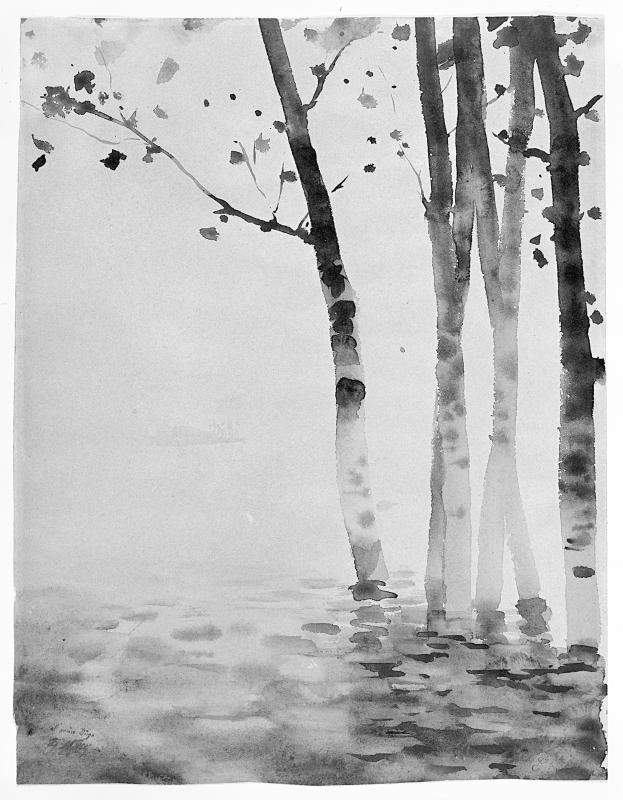

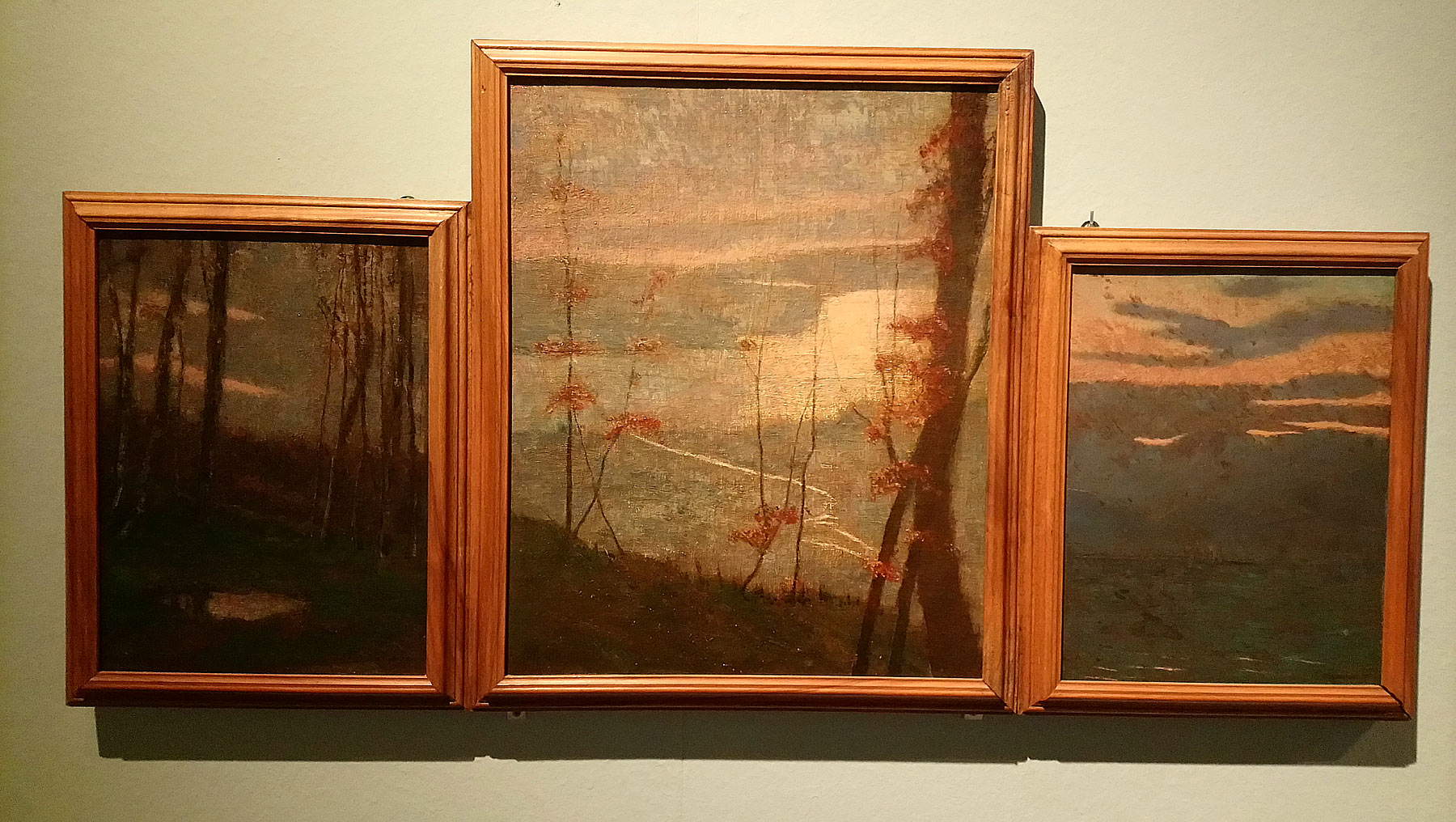

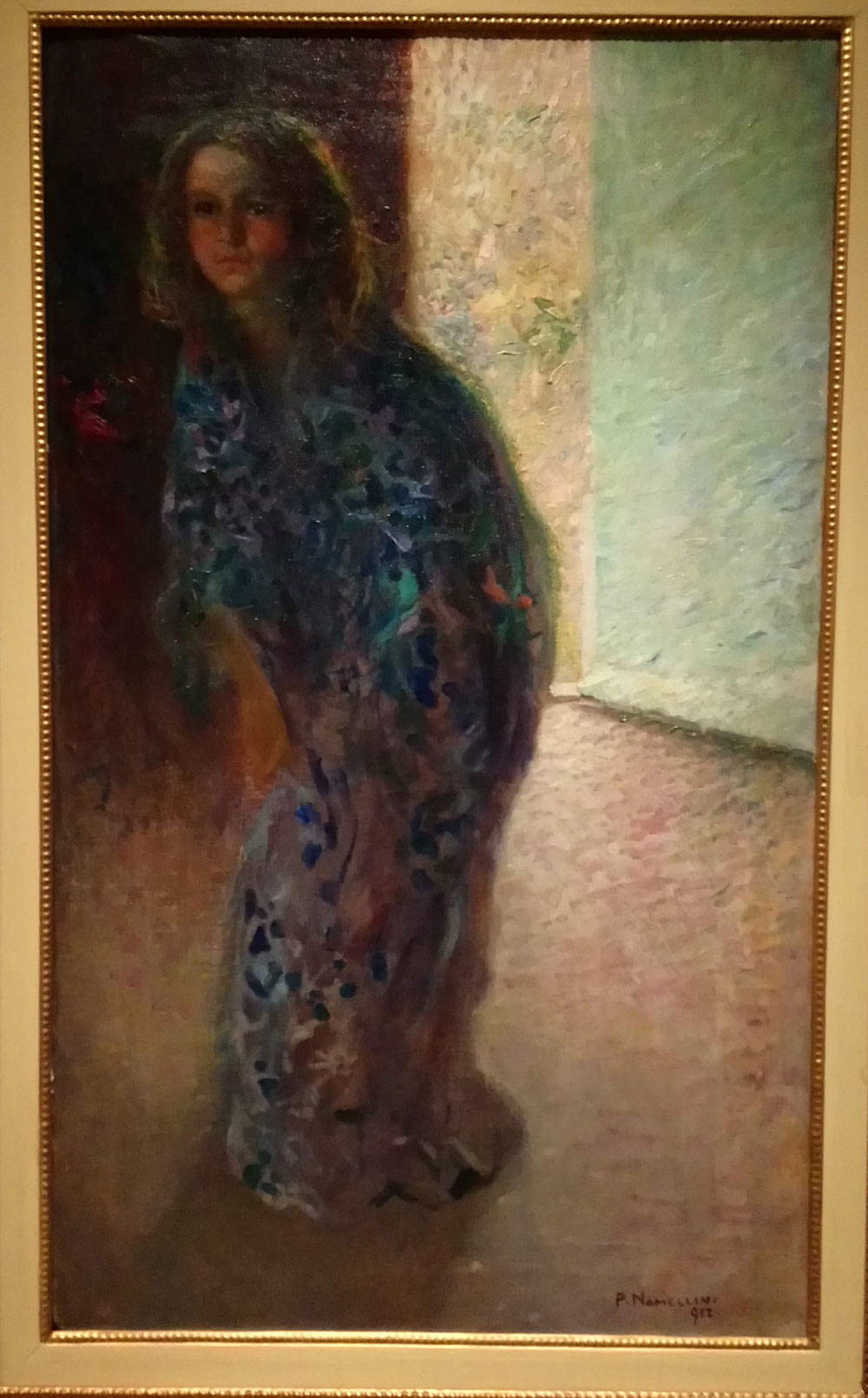

After two rooms finally devoted to Japanese art that inspired European artists (woodcuts, illustrated volumes, scrolls, sculptures and carvings, sword hilts, pottery, cups follow one another) and one on the “loans” of Japanism to advertising and publishing (the affiches of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, another key figure, appear), we come to the conclusion, and pick up where the exhibition began: the reception of Japanese art in Italy. Parisi writes that "although far from the great international circuits, Italian Japonisme nevertheless had a way of developing with the same diversification between Japonaiserie and Japonisme that had accompanied the evolutionary stages of this taste at the international level." There is no shortage, even at the end of the itinerary, of mannered Japonaiserie such as the crane attributed to Umberto Bellotto, an imitation of the imported sculpture counterparts that so appealed to the fin de siècle bourgeoisie (one of these objects is also described in Il Piacere), but the itinerary, in the final bars, focuses on the most innovative outcomes of Italian art, beginning with those touched on by Giuseppe De Nittis (Barletta, 1846 - Saint-Germain-en-Laye, 1884), the first artist to conduct a serious and thoughtful meditation on Japanese practices: his Skating Lesson, with elevated views, strong reduction of the color range, the figures on the left occupying almost the entire surface of the painting, shows that the artist had already assimilated the woodcuts of Hiroshige, and perhaps even closer to Japanese graphic art is the evocative watercolor Poplars in the Water, which seeks to restore not only the extent of the landscape in the manner typical of ukiyo-e printing, but also the muffled atmosphere through a technique similar to tarashikomi, which consisted of applying a second layer of paint when the first is not yet dry, in order to give life to random shades. De Nittis is also credited with having brought the Abruzzese Francesco Paolo Michetti (Tocco da Casauria, 1851 - Francavilla al Mare, 1929), present in Rovigo with La raccolta delle zucche (The Gathering of the Gourds) to Japanese art, where the perspective cut and the rendering of the vegetables (which amazed even his friend D’Annunzio) recall Japanese prints. On the other hand, a Japan that is both interior and decorative is at the basis of the landscapes of Vittore Grubicy de Dragon (Milan, 1851 - 1920), through whom the interest in the Far East would reach Segantini. Closing the exhibition is the Japaneseist declinations of the early twentieth century: apart from the exception of Galileo Chini (Florence, 1873 - 1956), capable of a new fusion of Art Nouveau and Japan (look at his Paravento con Damigelle di Numidia), for the other artists Japanese elements became good again, especially in a scenographic key, as can be seen from certain advertising posters of the time, beginning with the one for subscriptions to the Corriere della Sera designed by Vespasiano Bignami (more original formulas were proposed by artists such as Adolf Hohenstein or Marcello Dudovic), or by various pictorial proofs, such as the Bambina in kimono by a great artist such as Plinio Nomellini (Livorno, 1866 - Florence, 1943), a painting in which traditional clothing represents nothing more than an occasional access of oriental exoticism.

|

| Hans Makart, Die Japanerin (1875; oil on mahogany wood panel, 141.5 x 92.5 cm; Linz, Oberösterreichisches Landesmuseum) |

|

| Gustav Klimt, Woman Lying on the Right (1916-1917; pencil on paper, 316 x 493 mm; Vienna, Galerie Sylvie Kovacek, Spiegelgasse) |

|

| Emil Orlik, Landschaft mit dem Fuji im Hintergrund (1908; oil on canvas, 120.5 x 154 cm; Munich, Daxer & Marschall Gallery) |

|

| Albert Joseph Moore, Beads (1875; oil on canvas, 29.8 x 51.6 cm; Edinburgh, National Gallery of Scotland) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Skating Lesson (ca. 1875; oil on canvas, 54 x 73.7 cm; Milan, Le Pleiadi Art Gallery) |

|

| Giuseppe De Nittis, Pioppi nell’acqua (c. 1878; black watercolor on yellowed white paper, 326 x 251 mm; Florence, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampe) |

|

| Francesco Paolo Michetti, The Gathering of the Gourds (1873; oil on canvas, 78 x 98 cm; Naples, Private Collection) |

|

| Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, Triptych. At the Lakes or Alto and Two Basses, Evening Winter Morning, Miazzina. Summer Evening at Fiume Latte (1889-1919; oil on canvas, 32 x 25, 36 x 45, 32 x 25 cm; Turin, GAM - Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea) |

|

| Galileo Chini, Waves, damsels of Numidia and scorpionfish (c. 1910-1915; four-panel screen, oil on panel, 200 x 240 cm; Pisa, Palazzo Blu) |

|

| Plinio Nomellini, Child in Kimono (1912; oil on canvas, 100 x 60 cm; Private collection) |

The impetus of the avant-garde movements, the radical changes undergone by taste and collecting after the economic upheavals that followed World War I, the natural exhaustion of fashion for everything that came from the East, the fact that Japanese art, some fifty years after its “discovery,” no longer represented a novelty and the progressive Westernization of Japanese artists against which a 22-year-old D’Annunzio was already lashing out in the aforementioned article for La Tribuna (moreover, foretelling hard times for bibeloteurs, since the high demand for Japanese objects would cause price hikes), were among the reasons that led the Japonisist wave to fade more and more. Thus, the curtain falls on the story of an exhibition that, of course, is not the first dedicated to the theme, but which has the merit of providing the public (without neglecting the presence of some interesting unpublished works) with an overall view of the various downturns that Japanism underwent in the various areas of Europe, supported by a rich catalog that explores the main aspects (in addition to Parisi’s introduction and contributions by Jumeau-Lafond, Ranson Bitker, Carrera and Finazzi mentioned above, readers will find in it a summary by Rossella Menegazzo on artistic production in Edo- and Meiji-era Japan, an essay by Marco Fagioli on the relations between Impressionism and Japonisme, a view by Giovanni Fanelli on Japonisme in Symbolist illustration, and a paper by Anna Villari on the debts of poster art to Japan).

At Palazzo Roverella, Parisi has ordered an exhibition that is cultured (to which, fortunately, he does not care to highlight the presence of the usual big names, although there is no shortage of them) and marked by a path of quality, based on an anthological approach, which involves cuts (one example above all: Telemaco Signorini), but which is aimed at bringing out the souls of the various countries that received and elaborated Japonisme (and always keeping in mind that Italy’s role was not marginal), with an extremely varied selection, just as varied and far from organic was the response to Japonisme: the curatorial slant chosen for the exhibition renders this idea very well. An exhibition that, finally, emphasizes in particular the aesthetic features of Japonisme, rather than the philosophical or political ones (of which, in any case, the catalog to a certain extent gives an account): and this is because of the fact that Japonisme was first and foremost an aesthetic revolution, motivated mostly by aesthetic reasons, in the era of the advent of the camera, which would radically change the needs of artists and their very approach to their craft, their motivations, and their aspirations.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.