When one thinks of the union between Tuscany andcontemporary art, usually the first image that springs to mind is the great exhibitions that Palazzo Strozzi, with constant success with the public,reserves for the most celebrated names on the international art scene (it is worth mentioning, in the last three years alone, the exhibitions of Ai Weiwei, Carsten Höller, and Marina Abramović, and those of Tomás Saraceno and Jeff Koons scheduled for 2020), or the annual exhibitions that, for some time now, have been held in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria: from Jan Fabre to Urs Fischer, from Jeff Koons to this year’s dodecahedron to pay tribute to the five hundredth anniversary of the death of Leonardo da Vinci, the interventions that the City of Florence has envisioned for the city’s best-known and most recognizable square have always garnered a very high response, garnering heartfelt applause but also resounding criticism.

|

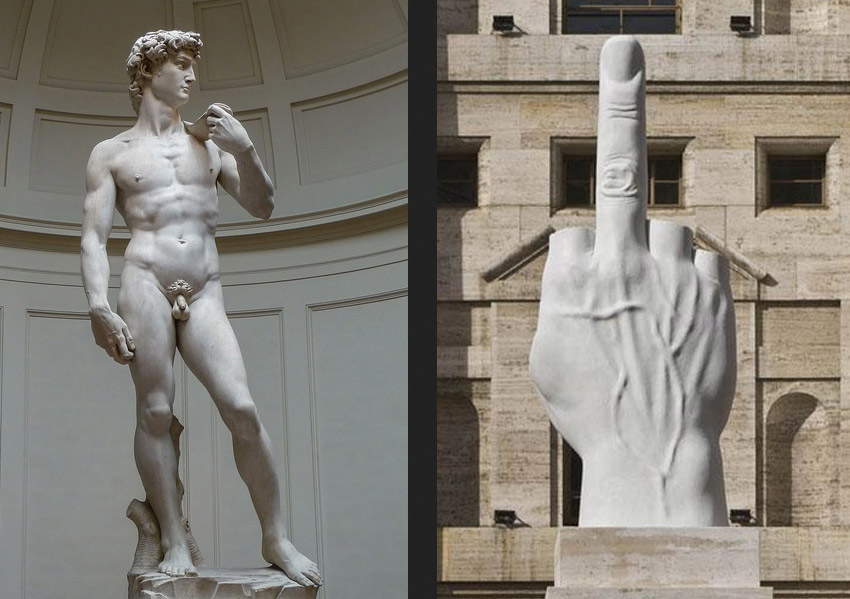

| Michelangelo Buonarroti’s David (ph. Credit Jörg Bittner) and Maurizio Cattelan’s L.O.V.E., two works by two great contemporary artists in their eras, produced entirely in Tuscany |

|

| Urs Fischer, Big Clay #4. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

Among the latter, it is interesting to point out one by Tomaso Montanari, who in November 2016, in an article in Repubblica, called for the City of Florence to create “something new” instead of “living off the backs of a past that you say you want to overcome, and instead you instrumentalize without restraint.” Of course: it is legitimate to have any opinion about Florentine cultural policies regarding contemporary art, but perhaps we also need to overcome the notion that there is nothing new in Florence and Tuscany. On the contrary: there is probably no region in Italy where the contemporary art system is as cohesive as it is in Tuscany and touches all aspects of the “supply chain” (pass this term borrowed from economic literature) in a widespread, capillary, lively way. What Tuscany lacks, if anything, is the awareness of being, in this sense, the Italian region with the highest potential. A potential that, however, is not fully exploited and of which citizens themselves (and perhaps administrators as well) have little awareness. For a contemporary art system to be able to say that it has a very high potential, there must be at least five pillars: places of education, centers of production, places of preservation and exhibition, commerce, and the ability to reach the peripheries. And Tuscany lacks none of these basic requirements.

To start with education, Tuscany has only two fine arts academies, but it can boast that they are among the best and oldest in the country. TheAcademy of Fine Arts in Florence has its historical roots in Medici Tuscany: one can consider as the first nucleus of the present institute theAccademia del Disegno that Giorgio Vasari founded in 1563 under the protection of Cosimo I de’ Medici (there followed, in 1784, the reorganization under Pietro Leopoldo I of Lorraine, which can be considered the moment when the Accademia as we know it today was founded, since it was as of that year that it became a public educational institution). TheAcademy of Fine Arts of Carrara, on the other hand, celebrated its first two hundred and fifty years of history this year: it was officially founded on September 26, 1769, by Maria Teresa Cybo, duchess of Massa and princess of Carrara, who, through the fledgling institute, aimed not only to train the younger generations of artists and artisans, but also to promote the working and trade of marble (the first director was, moreover, one of the greatest sculptors of the time, Giovanni Antonio Cybei). For the 2017-2018 academic year (the source of the data is the Ministry of Education, University and Research), the Florence Academy counted on 1,291 students enrolled, compared to 890 for the Carrara Academy: numbers that put them in tenth and thirteenth place, respectively, of the most attended academies (out of a ranking of thirty-eight institutions, including not only state academies, but also legally recognized academies). To assess the attractiveness of the two institutions, however, it is interesting to know the percentage of foreigners enrolled in academic courses: in this special ranking, Carrara, with 37.52% of foreign students, and Florence with 36.94% are at the top, occupying the fourth and sixth places (on the podium are the Academy of Fine Arts “Pietro Vannucci” of Perugia, the European Academy of Media Arts of Milan and the Albertina Academy of Turin, respectively with 55.96%, 48.04% and 39.17%, and the fifth place is occupied by the Academy of Fine Arts of Cuneo with 37.05 percent) and doing better than several academies with many more enrollments but evidently unattractive to foreigners (such as Palermo, 1.546 enrolled but only 18 foreigners, or Catania, 1,630 enrolled and 34 foreigners, or Naples, 2,703 enrolled of which 379, or 14.02 percent, come from abroad).

Both the Florence and Carrara academies forge strong relationships with international institutes, have set themselves the problem of thebreadth of their students’ training (in other words: academies no longer train only artists nor can they afford to do so: they, too, must now provide their students with the knowledge and tools to fulfill professionalizing paths) thus opening new courses in line with market demands (Carrara has focused heavily on digital technologies, while Florence has a viable school of artistic design for business that trains students in the fields of design, set design and space planning and stagingand a school of art didactics), and they have been trying for the past few years to strengthen their ties with the territory, especially through exhibitions and events (especially in Carrara, the memory of Maurizio Cattelan and Jeff Koons’ lectio is well alive, which also functioned as powerful means of aggregation for the city). It is usually customary to think that artists come out of the fine arts academy: as mentioned, having arrived in 2019, we can leave this preconception behind and evaluate the fine arts academies as institutions with a strong professionalizing vocation, which create value for the territory by training professionals who will go on to perform various professions, some of which are also in high demand on the market. Not only painters and sculptors then, but also designers, graphic designers, webdesigners, audiovisual technicians, video game programmers, interior designers, restorers, stylists, costume designers, photographers, set designers, curators, and teachers. The only note that can be introduced on this issue (but it should be noted well that it is not a problem of Tuscany, but of all of Italy) is the fact that the academies have embarked on a path that focuses far too much on professionalization: the artists of international caliber and the great critics or curators that the region has given the world in the last thirty years are very few, but the issue here is much broader and also concerns many other dynamics, starting with the support that Italy grants tocontemporary art and that is far less than that of countries such as France, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States that invest much more in contemporary art (and in the long run, this attitude will condemn our country to a marginal position in the art world: there will, however, be a way to explore this issue in more detail in our pages).

|

| Florence Academy of Fine Arts. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Academy of Fine Arts of Carrara. Ph. Credit Windows onArte |

It proves impossible, however, to talk about education without introducing the topic of production, since these are two closely related fields. From the two academies in the area come out graduates each year who will go on to replenish the region’s workshops (or open new ones). It is worth remembering that Tuscany counts on a large number of productive districts linked to art and craftsmanship: from the two best known, the marble district in Carrara and the ceramics district in Montelupo Fiorentino, to the alabaster of Volterra, the glass of Empolese, the pietra serena of Mugello, the crystal of Colle val d’Elsa, and the wrought iron of Casentino (moreover, each of these districts, except for the iron district of Casentino, has its own reference museum). It cannot be considered traditional, but another Tuscan excellence, that of the Pietrasanta foundries, is now of international significance. The academies are an indispensable link in the chain that unites schools, workshops, and businesses involved in arts and crafts: beyond the invaluable cultural value that an academy of fine arts offers to its territory (although in the future it will be necessary to focus more and more on a constructive dialogue between training centers and their areas of reference), there is no doubt that among the terms of the discussion is the economic value that academies help to maintain at high levels.

It is therefore appropriate to mention the two main examples, starting with that of artistic marble processing in Carrara. A 2014 survey by the Massa and Carrara Chamber of Commerce (with data referring to the year 2013) surveyed sixty companies active in the sector within the province, with an estimated total of 178 employees, with steady growth over the past five years. The numbers, however, grow if neighboring Pietrasanta is also considered: in the Versilia town alone there were 66 enterprises active in 2013 for a total of an estimated 271 employees, which placed Pietrasanta in first place in the ranking of Italian municipalities with the largest number of enterprises active in the artistic processing of stone products (Carrara is fourth, after Rome and Milan, but Tuscany occupies almost all of the “top 10,” with Florence in fifth place, Volterra in seventh, and Seravezza in tenth). The average turnover of companies in the province of Massa and Carrara was estimated at 217 thousand euros, with about 40 percent of production destined for the foreign market. This is a sector of excellence that gives a great deal to contemporary art: all the big names of the international sculpture star system cannot help but avail themselves of the collaboration of Carrara workshops to create sculptures that will then be admired all over the world. A few well-known cases are worth mentioning: Maurizio Cattelan ’s celebrated L.O.V.E. (vulgarly, the “middle finger” of Piazza Affari in Milan) was produced in Carrara; several of the works that thousands of fans saw at Damien Hirst ’s Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable exhibition in Venice in 2017 were made in the city at the foot of the Apuan Alps; many of Jan Fabre’s marble sculptures were born in Carrara. But the same could be said of Pietrasanta: it is in a Versilia foundry that saw the light, for example, of Giuseppe Penone ’s tree that left for the Louvre in Abu Dhabi. As for Montelupo’s ceramics, on the other hand, the Florence Chamber of Commerce, again in 2014, estimated the number of companies and the number of people employed in the district at 65 and 455, and even in the case of the town in the Empoli area we can speak of excellence in the sphere of contemporary art (suffice it to recall the name of Hidetoshi Nagasawa: the Japanese artist, shortly before his death, had collaborated with Montelupo and left one of his sculptures in the town).

|

| Sculpture workshop of the “Michelangelo” Art Studios in Carrara. |

|

| Maurizio Cattelan, L.O.V.E. |

|

| One of the sculptures in Damien Hirst’s Treasures from the wreck of the Unbelievable exhibition in Venice in 2017 |

|

| Jan Fabre’s marble Pieta |

Tuscany’s exhibition system can also count on some excellence, yet no one seems to notice. Apart from Palazzo Strozzi, which is an exhibition center run by a public-private foundation, and which does not always devote its programming to contemporary art (but when it does, as anticipated in the opening, it takes care to bring the “heaviest” names of the worldart system to Florence), Tuscany’s contemporary art museums disappear in front of their ancient art counterparts. The 2018 Museums of Tuscany report (a survey that the region conducts every year: the 2018 one, with data for 2017, is currently the most recent) certifies a rather bleak reality: in Tuscany, contemporary art museums (which do an average of 7.805 visitors each) have less appeal than ancient or 20th-century art museums (39,282 visitors on average), science and technology museums (24,695), archaeological museums (10,598), natural science museums (10,069), and history museums (7,959). Worse than contemporary art museums are only specialized museums (5,555), territorial museums (3,393) and ethnographic and anthropological museums (1,069). Moreover, the bulk of the total number of visitors who went to a Tuscan contemporary art museum in 2017 (a total of 78,051: to give an idea, the entire system of Tuscan contemporary art museums makes fewer visitors than the Museo Casa di Dante in Florence, 83,350 visitors in 2017, and is on the level of the Museum of Natural History of the Mediterranean in Livorno, 69.582, or Volterra’s Museo Etrusco Guarnacci, 73,241) focuses on a single museum, Prato’s Centro Pecci, Tuscany’s main contemporary art museum, which attracted 43,716 people in 2017 (down 29 percent from the previous year, when there were 61,577 visitors).

It doesn’t get any better if you want to broaden the picture by going to include the Museo Novecento in Florence (which has respectable contemporary art programming, although in the Regione Toscana report it is not profiled as a contemporary art museum): only 39,857 visitors for one of the most central museums in the capital. One could broaden the look by going to include the contemporary art parks (such as Daniel Spoerri’s Il Giardino in Seggiano or Niki de Saint-Phalle’s Tarot Garden in Capalbio), also an integral part of the system, but it is still only a few thousand more visitors. There is probably also an underlying problem of perception: the public (whether citizens themselves or tourists) lacks the awareness that Tuscany is a region strongly devoted to contemporary art. Consequently, if one thinks of Tuscany’s museums it comes naturally to imagine those that preserve masterpieces of ancient art or famous archaeological finds. Then there are more general problems concerning the scarce support that Italy, unlike other countries, grants to contemporary art (and the effect is that, in the international sphere, Italian artists have a hard time imposing themselves), but again these are issues that concern the whole country and not only Tuscany.

On the contrary, it would seem that the art scene in the urban peripheries is quite alive (also because Tuscany has a good tradition of street art and new forms of art: suffice it to think that the only work by Keith Haring designed to remain permanent, the mural Tuttomondo, is preserved in the region, in Pisa). In the region there are very active realities, such as the Leghorn gallery Uovo alla Pop, which last year gave life to the first edition of astreet art festival , moreover, focusing on the female component of the movement (as part of the event, the artist Gio Pistone, one of the main female street artists in Italy, was invited to Leghorn and donated one of her murals to the city). In Florence, it is also worth mentioning the work done by the Fondazione CR Firenze to restore the Palazzina dell’Indiano, which from decay has become an important cultural center dedicated to exhibitions, events, and performances. Still in Florence, again to mention the initiatives developed in the last year, a street art map has been created, with the location of places in Florence where street art can be created, produced and admired.

|

| The Pecci Center in Prato |

|

| Daniel Spoerri’s Garden in Seggiano. Ph. Credit Bernhard Holub |

|

| The Tarot Garden in Capalbio |

|

| Diana, Gio Pistone’s mural in Livorno. |

Finally, the contemporary art trade sector also appears alive: several galleries of national and international significance are based in Tuscany. To realize this, one need only scroll through the lists of exhibitors at what we can consider the three main Italian contemporary art fairs (Artissima, Miart and Arte Fiera). In particular, as many as twenty-three Tuscan galleries, namely, Frittelli, Il Ponte, Poggiali, Eduardo Secci, Tornabuoni Arte, Veda (Florence), Galleria Continua, Fuoricampo, Ph Neutro (Siena), Flora Bigai, Marcorossi, Poleschi, Prometeogallery (Lucca), Gli Ori, Me Vannucci, SpazioA (Pistoia), Armanda Gori, Open Art (Prato), Gian Marco Casini, Giraldi, Granelli, Guastalla Centro Arte (Livorno), and Alessandro Bagnai (Arezzo). It is, moreover, a very diverse system: there are historical galleries (think Tornabuoni or Frittelli), young galleries that attract good critical acclaim at the fairs in which they exhibit (often in sections reserved for new proposals), there are galleries that do research, galleries that manage world-class artists, and galleries that are suited to a less demanding public. Even in the contemporary art trade, Tuscany plays a leading role (in this sense, more active than Tuscany is probably only Lombardy). What is lacking is a major fair of international caliber: the festivals held annually on Tuscan soil, however interesting they may be, are still interregional or regional in character, and in Tuscany there are no fairs on a par with those mentioned above, capable of attracting an international audience and large collectors. And when one considers that one of the world’s largest antique art fairs is held in Tuscany (the Florence Biennale Internazionale dell’Antiquariato), it might be an exceedingly interesting idea to place alongside it a contemporary art fair that could rise to equal prestige. Take into account the fact that often those who buy high-level antique art are equally interested in contemporary art, so much so that formulas capable of combining ancient and contemporary are spreading (such as Flashback in Turin) and others that have instead decided to “double up” (this is the case of Frieze, active since 2003, and which in 2011 launched a sister fair, Frieze Masters, dedicated to art from antiquity to the twentieth century).

All in all, Tuscany is perhaps more than any other region of contemporary art. But it doesn’t know it is. And probably the main issue here is a problem of communication: internally it pertains to the sphere of awareness, externally to that of perception. It is perhaps not a systemic problem, since all the actors involved have a very high potential. Which, however, struggles to impose itself: therefore, Tuscany should work to build a new self-image around contemporary art. After all, it can certainly be said that Tuscany has always been throughout its history a center of contemporary art production, which has never stopped: Giotto, Botticelli, Michelangelo were, after all, contemporary artists. Action should follow some basic lines: targeted marketing campaigns, a change in cultural policies on the contemporary (there is a lack, with rare exceptions, of strong direction and long-sighted programs), the ability to attract not only world-class artists (which Tuscany already succeeds in doing) but also critics and curators of equal standing, increase support for promising young artists, and make the links between the territory and the centers of the system (whether they are those of education, production, conservation or commerce) firm. Roads still largely to be explored.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.