Let’s face it: getting to Volterra is not exactly the ultimate in convenience. Cut off from the vast majority of public transportation routes, the fastest way to get there is by using your own car: arriving in Ponsacco, for those coming from the north, there is almost an hour’s drive through the Tuscan hills.

When you arrive, however, you feel deeply rewarded for the journey, from the very first glance, because a wonderful medieval town clinging to the top of a hill opens up before you, its buildings having the same color tones as the balze, the clayey chasms that surround the town. We park the car and set out to discover Etruscan and Roman Volterra.

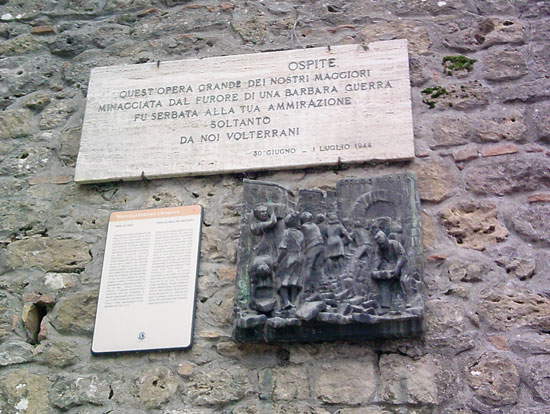

That welcomes us right away, because to enter the town, the ancient Velathri of Etruscan foundation, precisely (although on the hill on which the town was built, there were already settlements from earlier periods), we pass under the Porta all’Arco, the huge portal that opens on the southern side of the walls, which we see partly incorporated into the medieval architectural fabric. The piers, that is, the vertical elements that support the arch, were made of large blocks of tufa stacked on top of each other, and are the only parts of the gateway that survive from the time of the Etruscans (fourth century B.C., the time to which the Etruscan walls date), because the arch is later, we are already in Roman times, perhaps in the second century B.C. The three statues that adorn the arch probably also date to this period. We are not sure who they represent: perhaps Jupiter in the center and on either side the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux, or the Capitoline Triad (Jupiter, Juno and Minerva). However, we are not sure what the purpose of these heads was. A plaque and a relief, affixed to the wall in which the gate is embedded, recall the event that affected it on the night between June 30 and July 1, 1944, during the last stages of World War II: the retreating Germans, in order to hinder the advance of the Allies, decided to blow up the Porta all’Arco. However, the people of Volterra provided a very high example of love for their heritage: upon hearing the news, they asked the Germans to save the gate. The Germans agreed, on one condition: the inhabitants of Volterra would have to obstruct the gate so that the Germans could achieve the same goal. The citizens thus set to work, and between the afternoon of June 30 and the morning of July 1 they managed to erect a bulwark behind the gate: they used the slabs of the road going up, which were removed and placed against the Porta all’Arco. Today the plaque (along with the relief depicting the citizens at work around the gate) reminds everyone that if that gate can still be admired, it is thanks to the tenacity, passion and courage of the citizens of Volterra, and their heroic act: a very high example of love for history.

|

| The Gateway to the Arch of Volterra |

|

| The plaque and relief commemorating the events of 1944 |

We walk through the entire historic center, which has a medieval feel, to arrive on the opposite side of the village. But not before stopping for a moment near the Cathedral, because from the widening near the Baptistery, namely the Piazzetta dei Fornelli, there is a beautiful view of the entire valley surrounding the hill on which Volterra stands. We were saying, we walk towards the opposite part of the town: coming down from the Piazzetta della Pescheria, we meet a road that runs above a section of the walls(via Lungo le Mura del Mandorlo) and that gives us the opportunity to enjoy, in front of us, a view of the buildings of the eastern part of the city, and on our own left, looking down, we observe instead the remains of the Roman theater, from the Augustan period. We are therefore between the first century before Christ and the first century after. The site on which the theater stands was not occupied by any buildings in Etruscan times: the planners therefore took advantage of the physical conformation of the site, which is slightly sloping, so as to facilitate the construction of the tiers of seats, which are partly preserved. Below the bleachers we notice a semicircular space: this is the so-called orchestra, that is, the place where the musicians and chorus who accompanied the theatrical performances took their seats. The rectangle we see immediately in front was the stage, and the corridors on either side of it were the corridors used by the actors to reach the dressing rooms that were located behind the stage. The back porches, on the other hand, are part of the stage, which served as the backdrop. Behind the theater, we can also see the remains of the baths, which were built in the 4th century AD, reusing some materials from the theater, which had not been used for a hundred years.

|

| The Roman theater of Volterra from above |

We then return to the medieval center for the third stop on our journey: the Guarnacci Museum, one of the most important museums in the world for Etruscan history. It is dedicated to Abbot Mario Guarnacci (Volterra, 1701 - 1785), tireless archaeologist and author of numerous finds in Volterra and the surrounding area: in 1761 he decided to donate his patrimony to the municipality, and that was the first nucleus of the museum that today bears his name. A must-visit for all those who want to learn more about Etruscan Volterra: the itinerary, organized in chronological order, takes the visitor on a journey from the birth of ancient Velathri to the highest testimonies of Etruscan art. Among the latter, not to be missed are theOmbra della Sera, a bronze votive statuette depicting a child of elongated proportions (from which it would derive its name, given to it by Gabriele D’Annunzio), and theurn of the spouses, the highest example of an Etruscan cinerary urn preserved at the museum. There is also a large collection of artifacts that take us into the daily life of the Etruscans, and a room devoted entirely to cinerary urns, often resembling small sarcophagi. In the museum, there is also a section devoted to Roman Volterra.

|

| The Shadow of the Evening. Credit |

|

| The urn of the bride and groom. Credit |

So after a visit to the Guarnacci Museum, evening begins to set in. And there is no better place to enjoy the sunset over Volterra than the archaeological park of the Acropolis, the final destination of our journey through Etruscan and Roman Volterra. Here, on the highest point of the city, excavations have unearthed the remains of the Velathri quarter in which temples dedicated to deities were concentrated. Built several times even in Roman times, today the temples survive only in their foundations: walking through the park it is possible to linger, to see the stones, the walls of the ancient buildings, to know their history. These are the vestiges of the glorious past of one of the most important centers of Italy more than two millennia ago.

|

| The acropolis of Volterra, with the city in the background |

|

| The view from the acropolis |

|

| Shadows fall on the greenery of the acropolis archaeological park |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.