by Nataliia Chechykova, published on 15/12/2020

Categories:

Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Short trip to the 17th- and 18th-century Italian collection of the Odessa Museum of Western and Oriental Art, one of the most important museums in Ukraine.

At a time of forced closure of our Italian museums, we are forced to satisfy our craving for art by going around the Web to look for the virtual collections that almost all the world’s great exhibition venues have more or less hastily put together or simply updated to satisfy our desire for the “beautiful.” Unfortunately, not all museums, especially the smaller and less economically equipped ones, can afford these wonderful technological tools. So I thought, for those who still love the pleasure of discovery, for those who still want to marvel at looking at works that they have never seen and perhaps never thought existed, to take you to a place decidedly far from our Italy, to Odessa. A Ukrainian city on the Black Sea founded in 1794 at the behest of Catherine II the Great to give her empire at last a port to the West.

Deeply Slavic in its origins, but built mainly by Italian architects in the strictest adherence to a typically French urbanism, the training place of revolutionaries such as Lev Davidovich Bronshtejn, better known as Trotsky, but also the ideal place where Vassily Kandinsky was trained, the city of the father of Zionism Vladimir Zhbotinsky and a key place of cinephiles around the world for its “Potemkim staircase”; and perhaps for Italians unknown home of one of our country’s most famous songs, O’ Sole Mio (written in Odessa itself by Edoardo Di Capua in 1898). Well, in such a “diverse” and multiethnic city there certainly could not have been a lack of a museum in which this international nature of itss was not reflected in the best possible way: the Museum of Western and Oriental Art. A facility inaugurated only in 1924 at the behest of the young Soviet Republic in which converged all the works of European art that the regime had confiscated from nobles, merchants, and art lovers of the great Odessa region, which at that time stretched from Romania to Crimea. It was an impressive amount of works, if we think that the first catalog of 1924 counted as many as 308 works on display, not counting, of course, those that haphazardly filled the museum’s storerooms.

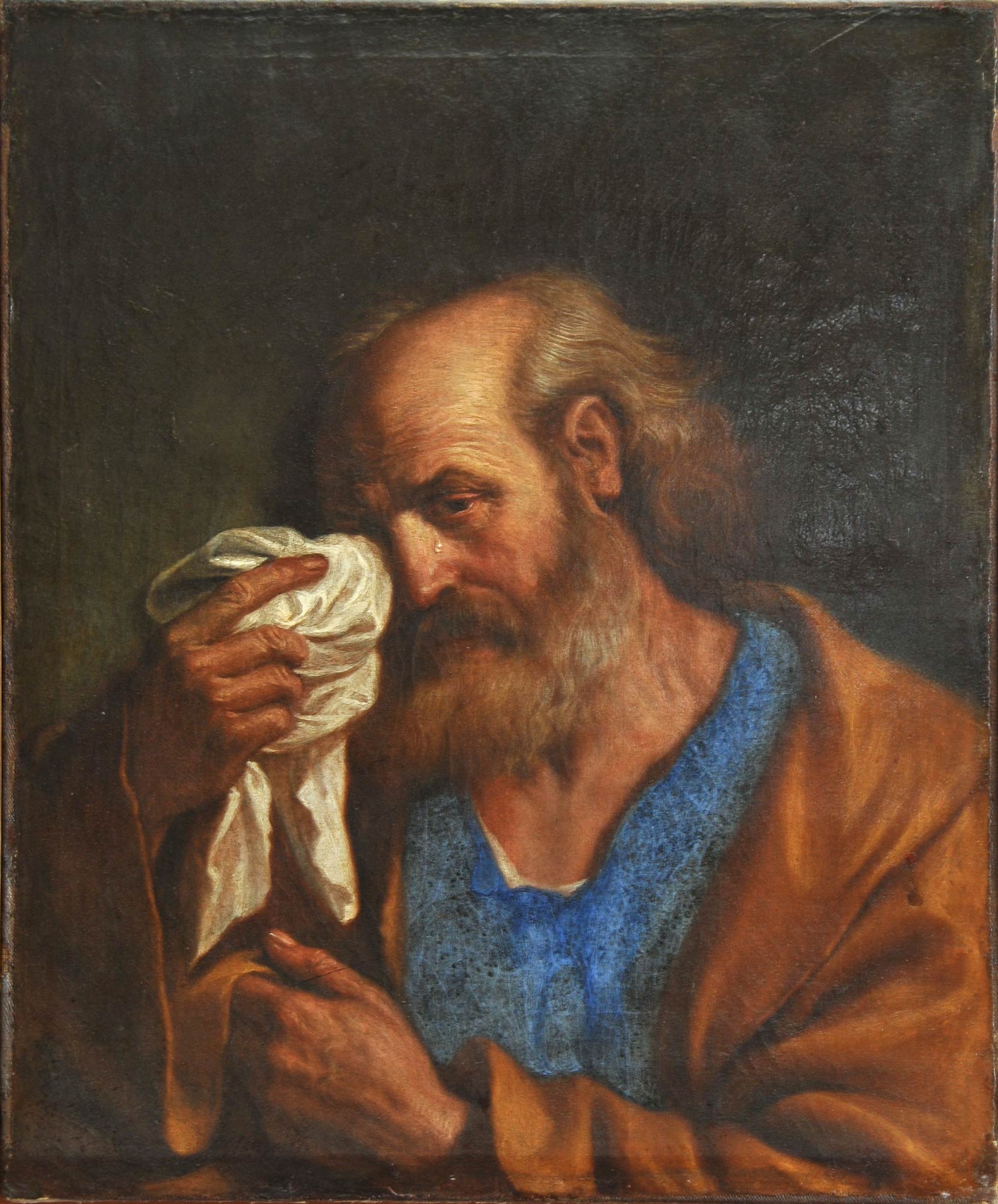

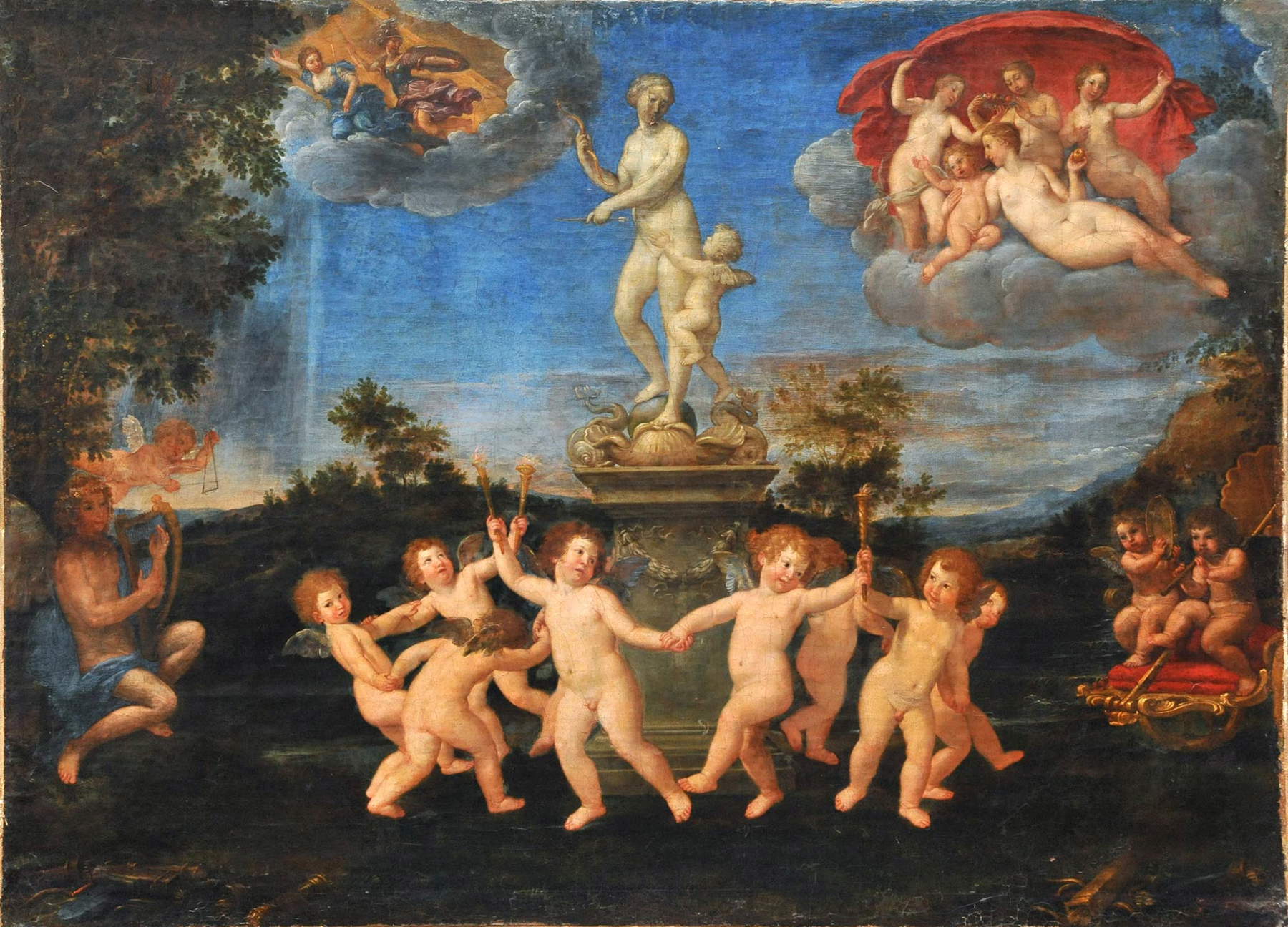

Since it is impossible to recount all the works in this small-big museum (currently its inventory only counts 607 works from all European schools among the paintings), I decided to focus this brief narrative on two centuries of Italian painting present in the current picture gallery, the 17th and 18th centuries. Obviously, the first masterpiece to be mentioned is one that our readers already know because in recent months we have been following its vicissitudes step by step: the Capture of Christ (fig. 2), a replica or copy, still to be defined, by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (Milan, 1571 - Porto Ercole, 1610). But in this article I would like to introduce you to the other masterpieces that this little museum treasure chest has never had the chance to make known, especially to the Western world. Starting with Bolognese artists: the first one to mention can only be a languid, poignant weeping St. Peter (fig. 3), by the Cento-born Giovanni Barbieri known as Guercino (Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666), a work from the collection of Count Musin-Puskin-Brus, donated to Tsar Nicholas I in 1856, on display in the great St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts until 1901 when together with other works it was moved to the city of Odessa. An excellently crafted work, it is strikingly reminiscent of the other more famous Weeping St. Peter in the , but somehow more dramatic in its depiction of the loneliness of the Man-Peter (fig. 4). And then there is the cheerfulness, joy but above all the stylistic perfection of Francesco Albani (Bologna, 1578 - 1660) with his Triumph of Venus, an oil on canvas, unlike the more famous works of Brera and Dresden (oils on copper), which also because of its size (82 x 111.5 cm) makes the enjoyment of the “little stories” that frame the Venus to her cupids, impeccable(fig. 5).

In large numbers are the Venetian artists or those who became Venetian by adoption present in the rooms, and since I cannot mention them all I will limit myself to pointing out a few starting with the one who is certainly not Venetian, but who made the lagoon city his new home: the French-speaking Belgian Nicolas Régnier (Maubege, 1591 - Venice, 1667): with his only canvas in the collection, Circe, which has been abandoned in storage for years because lack of funds does not allow for its proper restoration, a work that just these days I was able to have examined by art historian Annick Lemoine, a great expert on the Belgian painter, who did not know of its existence (fig. 6). And this very episode is yet another proof of this museum’s main problem: few people know about it and even fewer imagine how many valuable works it has in its picture gallery.

|

| 1. The Odessa Museum of Western and Oriental Art. |

|

| 2. Da Caravaggio, Capture of Christ (early 17th century; oil on canvas, 134 x 172.5 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 3. Guercino, Weeping Saint Peter (oil on canvas; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 4. Guercino, Weeping Saint Peter, detail |

|

| 5. Francesco Albani, Triumph of Venus (oil on canvas, 82 x 111.5 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 6. Nicolas Régnier, Circe (oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

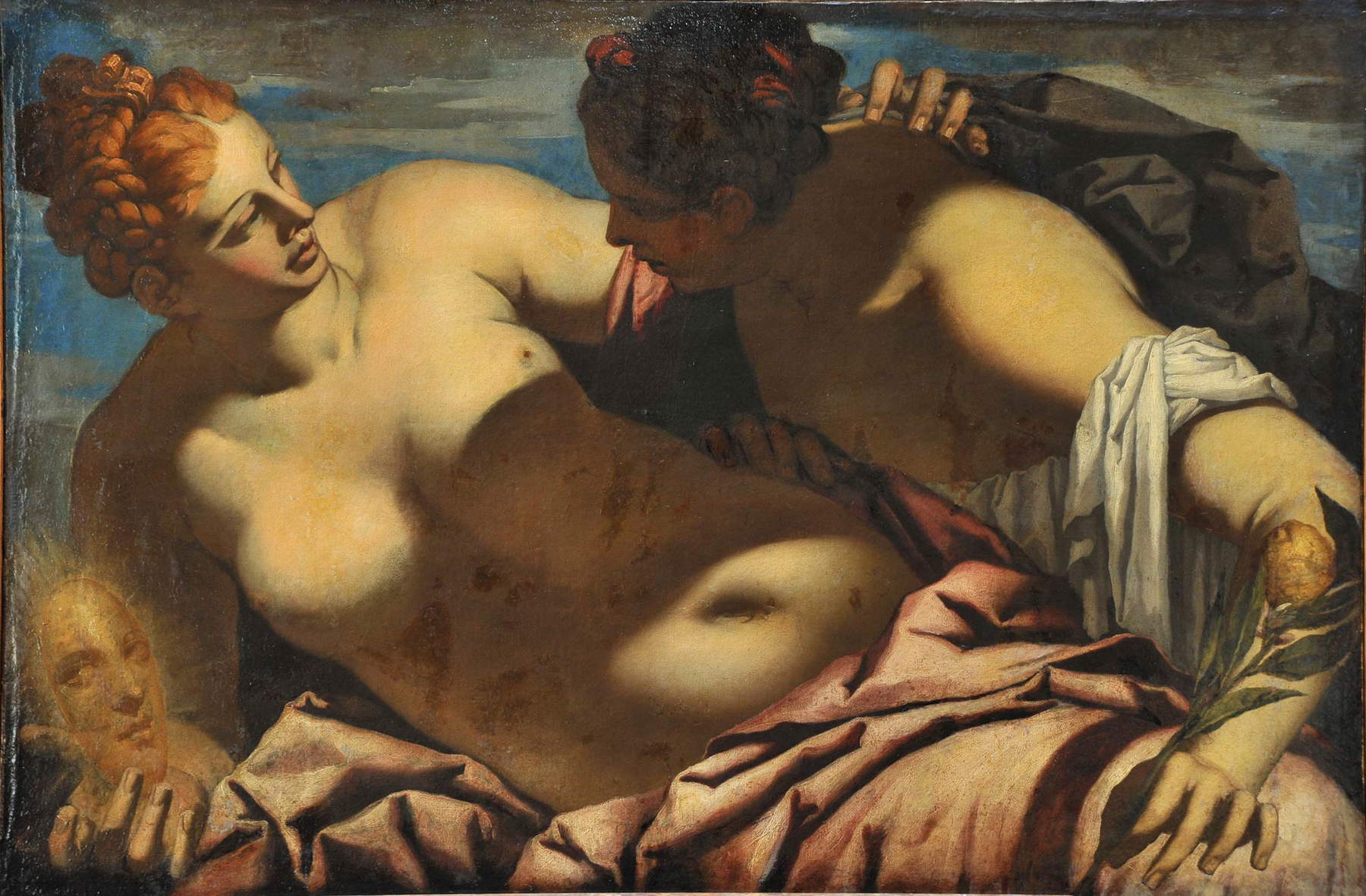

But continuing in our narrative, and remaining among Venetians always by adoption, here we come to Francesco Ruschi (Rome, 1610 - Treviso, 1661), Roman by birth but who found in Venice and then in Treviso his artistic affirmation with excellent works especially in fresco, of which in the museum we find one of his mighty canvases, theAllegory of Truth and (fig. 7). In this case it is difficult to attempt any comment, the canvas overwhelms you with its vivid colors, with this interweaving of female bodies hovering in an absolutely indecipherable space. The list of works by Venetian artists in the exhibition is truly remarkable, from Pietro Liberi to the superb Canaletto and Guardi with their unmistakable glimpses of calli, campielli and canals, but of two artists I would like to propose two very singular canvases, one truly peculiar and unusual, the Sacrifice of Iphigenia (fig. 8) whose attribution to Andrea Celesti (Venice, 1637 - Toscolano, 1712) is still being debated, but which is astonishing for its composition “filled” with characters in despair from that dramatic but necessary sacrifice, and again by Celesti the Eliezer and Rebecca (fig. 9) a truly beautiful canvas, in which this delicate figurine of a young girl, Rebecca, stands out, who though with a tender blush on her cheeks is caught at the moment of taking upon herself the great responsibility of becoming the mother of God’s new people. And then one of the most beloved and painted themes of the time could not be missed: an “Ecce homo” (fig. 10) by the Genoese, Venetian by artistic adoption, Bernardo Strozzi (Genoa, 1581 - Venice, 1644). A canvas filled with the passion of Christ that the Genoese priest seems to have felt in his own limbs by pouring it into his composition, a work in front of which it is difficult not to feel emotionally involved in the Savior’s drama.

The number of Italian works in this museum should come as no surprise: beyond the Italian architects who built the city, Odessa was for years a “free port,” and of course there could be no shortage of Venetian and Genoese merchants and shipowners, with their rich mansions concentrated right in today’s central Puskin Street, where the Museum is located, which until 1880 was the Italians’ Street(Italianskaya uliza). Moving again among the authors from northern Italy, we cannot fail to mention Stefano Maria Legnani known as Legnanino (Milan, 1661 - Bologna, 1713) with two works presumably born as pendants, one full of pathos, Judith (fig. 11) and the other, a fragile, timid and helpless Susanna and the Old Men (fig. 12). Another Milanese doc, even baptized in the same parish as Caravaggio, Francesco Cairo (Milan, 1607 - 1665), has in his collection one of his marvelous heroines, Portia (fig. 13), an ecstatic and fascinating portrait of a woman that the sublime technique of this inwardly conflicted master delivers to us in this work as a piece of his world: between dream and nightmare. Another adopted Lombard working mainly in the provinces of Brescia and Bergamo is the Austrian Giacomo Francesco Cipperdettoil Todeschini (Feldkirch, 1664 - Milan, 1736): he, too, with his “Breakfast” (fig. 14), projects us with his tragic-ironic manner into the other seventeenth century the one without silk, candelabra and beautiful maidens: in a humble but dignified tavern scene. A large canvas focused on four characters who between a piece of dried bread and a nice touch of cheese are presumably finding love. Unfortunately, this work is also currently relegated to storage awaiting urgent restoration, but perhaps in this case its characters will get over it; they have been frequenting damp and dark surroundings forever, let’s just hope we don’t get used to it. But back to the beautiful rooms colored in soft pastel colors illuminated by the large windows from which the sun enters everywhere, the ideal place for a good visitor-photographer we find, a real explosion of Alessandro Magnasco (Genoa, 1667 - 1749) who with no less than four canvases immerses you in that world of this Genoese artist made of dark and sometimes frightening landscapes or interiors that in the frenzy of his extravagant characters seem to place themselves in a circle of Dante. In his works, a Tonsure of Monks (fig. 15), In the Guard Post (fig. 16), Mary Magdalene (fig. 17), Landscape with Figures (fig. 18), all different in their themes and characters, you can find all the flair of this Genoese master, among the few who manage to excite, but above all amaze, for his creative imagination.

|

| 7. Francesco Ruschi, Allegory of Truth and Mercy (oil on canvas, 71.2 x 106.8 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 8. Andrea Celesti, Sacrifice of Iphigenia (oil on canvas, 138 x 175 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 9. Andrea Celesti, Eliezer and Rebecca (oil on canvas; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 10. Bernardo Strozzi, Ecce homo (oil on canvas, 123 x 98 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 11. Stefano Legnani known as Legnanino, Judith (oil on canvas, 146.8 x 191.3 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 12. Stefano Legnani known as the Legnanino, Susanna and the Old Men (oil on canvas, 148 x 193 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 13. Francesco Cairo, Portia (oil on canvas, 113 x 95 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 14. Giacomo Francesco Cipper known as the Todeschini, Breakfast (oil on canvas, 112 x 135 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 15. Alessandro Magnasco, Tonsure of Monks (oil on canvas, 99 x 73 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 16. Alessandro Magnasco, In the guard post (oil on canvas, 49.5 x 119 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 17. Alessandro Magnasco, Mary Magdalene (oil on canvas, 69 x 54 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 18. Alessandro Magnasco, Landscape with Figures (oil on canvas, 91.2 x 117.9 cm; Odessa, Museum of Western and Oriental Art) |

|

| 19. National Opera and Ballet Theater of Odessa Fellner & Heimer (1887) |

|

| 20. Potemkim staircase by Francesco Boffo (1841) |

I realize that this is but a small sampling of this fine museum, but it is meant to be a sort of invitation, pandemic permitting, for an upcoming possible trip for those who are eager even without even much spirit of adventure to visit a new place. Now Odessa is connected by the largest Italian airports at least three times a week with low-cost flights. And visiting Odessa means not only this museum, but also another dedicated to Russian Art ranging from traditional icons to the best works of the pictorial avant-garde, and then the sumptuous National Opera House designed in perfect neo-Baroque style (fig. 19), which makes it possible to attend operas and ballets with daily performances ranging from noon to 7 p.m., something unthinkable in Italy, and finally the grand, majestic Potenkim staircase (fig. 20), also the work of course of an Italian architect, Francesco Boffo.

The author of this article: Nataliia Chechykova

Storica dell'arte, Consulente per l’Arte Italiana del Museo di Odessa.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.