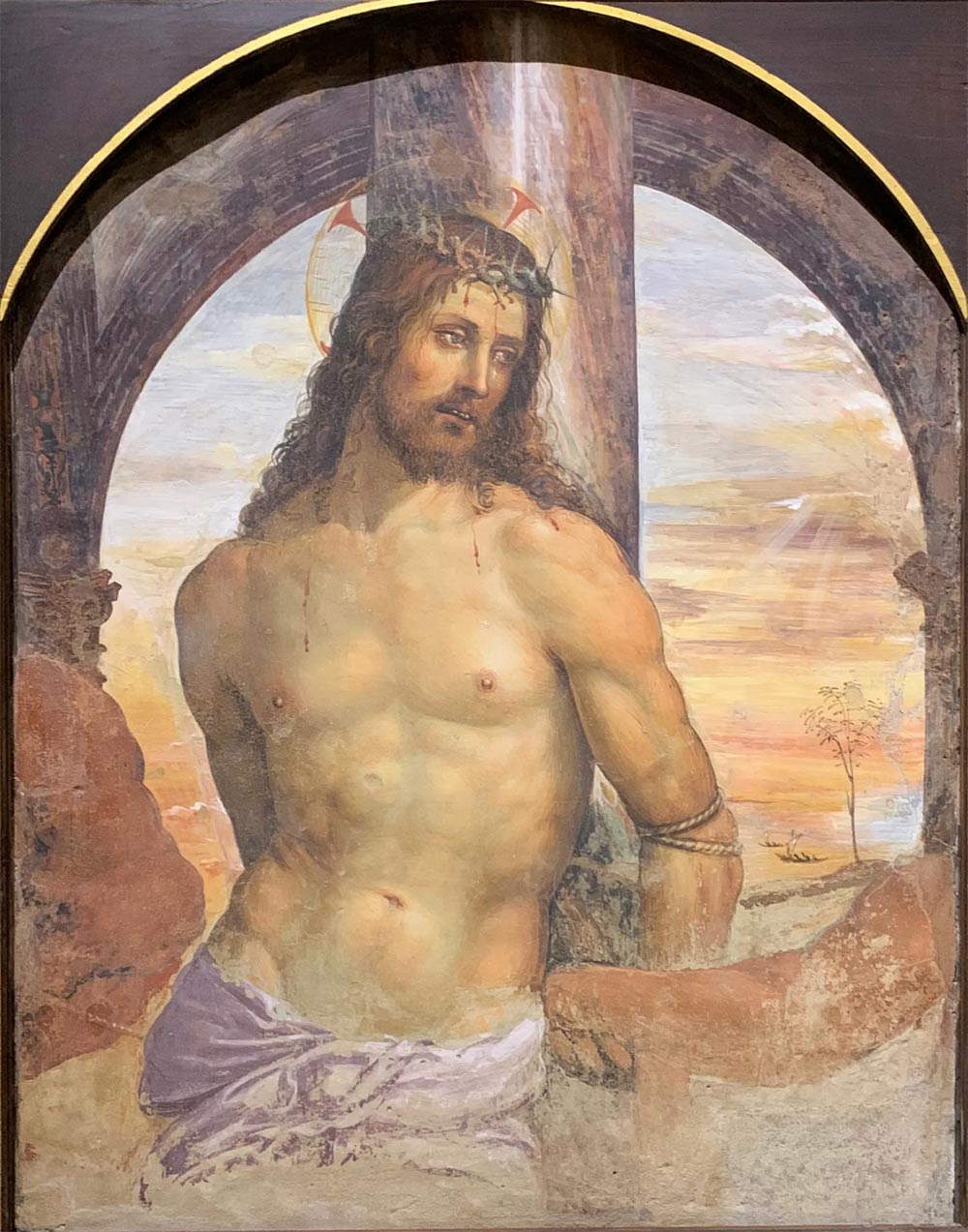

The story behind Sodom’s Christ at the Column , preserved at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Siena, is curious and singular. It is a detached fresco: in ancient times it stood in the cloister of the convent of San Francesco in Siena, where the artist had painted it around 1515, commissioned by Fra’ Luca da Montepulciano, on a wall in contact with a kitchen and a well that ended up ruining it irreparably and making the detachment inevitable. The central part of the fresco was thus removed in 1841, and immediately transferred to the Accademia Gallery, as what would become the Pinacoteca Nazionale was then called. Given its history and the interest it aroused from that time on, Christ at the Column by the great Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, Piedmontese by birth and Sienese by adoption, can count on a solid critical fortune. And the interesting fact is that the laceration from the convent of San Francesco more or less puts everyone in agreement, even the detractors of this eccentric artist capable of unparalleled splendor, energetic and graceful at the same time, delicate and powerful, composed and balanced but able to make his characters give off the most overwhelming feelings for those who observe them.

So many have been the critics who have adhered to the moralistic judgment of Vasari, who in his Lives crushed Sodom by premising from the outset that if this painter had studied as he would have been able to do, “he would not at the end of his life, which was always stratta e bestiale, have been led madly into old age to stint miserably”, without perishing to brand him as a “cheerful man, licentious, and held others in pleasure and amusement, with not very honest living,” and attributing his nickname, rather than to the Tuscanate mispronunciation of the Piedmontese intercalary “su ’nduma,” to his rumored sexual mores. In fact, despite his eccentricities (beginning with the bestiary he kept at home: he had cats, monkeys, donkeys, horses, squirrels, even a badger, in whose company he depicted himself in the famous self-portrait of Monte Oliveto Maggiore), Sodom was a highly sought-after artist in his time: he worked for Pope Julius II, for Agostino Chigi, for the Appiani of Piombino, for a large number of religious patrons, and had occasion to deal with the Gonzagas. And the scene he had painted for the Franciscans in Siena, that “Christ beaten at the column, with many Jews around Pilate and with an order of columns drawn up in perspective for the use of curtains,” as Vasari described it, letting us, moreover, imagine the extent the scene must have had, has always been considered among his best things.

Weighing on the consensus that Christ at the Column would obtain after it was detached from the wall of the cloister of San Francesco was, in all probability and according to what might appear as a paradox, the very removal from the place where Sodom had painted it: it was Cesare Brandi, in his 1933 guide to the “Regia Pinacoteca di Siena,” who wrote that Giovanni Antonio Bazzi’s painting is a “celebrated masterpiece which, however, from the mutilation that isolated it almost providentially received a greater grandeur.”

Undoubtedly the fact that, for more than a century and a half, Christ at the Column has been seen alone, out of its context, without the surrounding figures, in all its statuesque monumentality, has certainly contributed to conditioning the way we see it. But Sodom’s work had nonetheless aroused enthusiasm even earlier. In the eighteenth century it fell to Father Guglielmo Della Valle, a Franciscan friar and excellent writer on art, to restore that painting, which was already then in a very poor state of preservation. And evidently it was not only for reasons of familiarity with that image that Della Valle gave it a lofty judgment: in the Christ at the Column of St. Francis, he would write in his Lettere sanesi sopra le belle arti, is to be found “all the sublime and beautiful ideal of art.” Guglielmo Della Valle did not allow himself to be shaken by moralisms about Sodom because few other times in the history of art has the figure of Christ tied to the pole to be scourged succeeded in achieving similar results of formal perfection, compositional balance, and balanced command of feeling. Similar to a Greek Apollo, Christ at the Pillar bears the memory of the ancient marbles that Sodom had studied in Rome during his formative years: in his mind, wrote Roberto Bartalini author of some of the most valuable studies on Sodom, the memory of the Laocoon seen in the courtyard of the Belvedere in the Vatican was well fixed, “the motion of suffering of that agitated body”, the disruptive vigor of that “paradigm of anatomical realism and physiognomic expressiveness” that would continue to inspire certain figures to the Piedmontese artist in a more or less larval way for years.

We see his half-length Christ, from the thighs up, against the background of a reddish sunset that bathes the sea in the distance in light. His face, framed by a cascade of brown curls and a stubble that grows irregularly, is furrowed by a few tears: whoever looks at this Christ is touched by his composure, by the calmness with which he faces his sacrifice, which nevertheless does not prevent him from holding back his suffering. The son of God made man shows here all his humanity, despite the fact that to some nineteenth-century commentators the face of the Jesus of Sodom appeared cold and almost abstract: it is, if anything, the opposite. Suffice it to see, in addition to the eyes, the mouth revealing the upper dental arch: one seems to feel it, the labored breathing of this Christ.

The column to which he is tied simulates marble realistically, believably, complete with a ray of light reflecting vertically in the part closest to the relative. Scarcely credible, however, is the thin rope that is supposed to hold firm and immobile that body so perfect, athletic and sensual, and probably capable in the past of depriving more than one friar of sleep, if one were to take the cue from the American scholar Patricia Simons, who compiled the Sodom’s entry in Claude J. Summers’ encyclopedia of queer art. Summers, careful to emphasize the fact that the monks could “enjoy the sight” of that muscular and curvaceous Christ.

Now, regardless of what one wants to think about Sodom’s intentions, there is no doubt that the body, in Renaissance art, plays a central role: and in painting this Christ at the Column , Sodom shows himself to be not only attentive to the anatomical studies of Leonardo da Vinci, an artist from whom he knew how to draw more than one cue, but also aware of the potential of the image. The realism of Christ’s body was to be, Leo Steinberg has written, “an ostensive act, a palpable proof” of God’s incarnation, of his becoming man: the image of Christ suffering during the Passion becomes, recalling Plato, an object that is capable of being seen and known by means of divine intelligence, diffused in the world of the senses, and responsible as much for truth to the object of knowledge as for the faculty of knowledge to the subject. This necessity of truth and knowledge passes in the Renaissance through the equally necessary representation of bodies that, like that of the Christ of Sodom, appear sensual to us. Then there are reasons that lie in Sodom’s interests: his masterpieces often appear animated by his “penchant for a classicism predominantly faithful to Raphael’s ideal of beauty and grace, pursued through figures in harmonious and cadenced poses,” as Laura Martini has written. We return then to what Father Della Valle wrote: the sublime and the beautiful in art live on in this summit of early 16th-century painting. The Greeks, Della Valle said, “would not have made a patient Jupiter more majestic.”

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.