When, in the Basilica of St. Dominic in Bologna, one enters the chapel dedicated to the Spanish saint and looks at theArk of St. Dominic, the monument that holds his remains, one is immediately captivated by the monument’s grandeur, fascinated by its fineness, its singular forms, the narrative verve of the sarcophagus’ scenes, and surprised to learn about its history, which tells us about a work whose realization went on for centuries. When the Ark of St. Dominic was conceived, however, it was also one of the most innovative works of that historical moment. It was 1264 when the Dominicans of Bologna decided to erect a sumptuous ark that could worthily house the remains of St. Dominic of Guzmán, who had died in Bologna just over forty years earlier, on August 6, 1221. The decision, moreover, as explained by the scholar Anita Fiderer Moskowitz author of one of the most recent and dense contributions on the Ark, was made in blatant violation of the rules introduced in 1261 by the Order of Dominican Preachers itself, when general of the Order was Umberto di Romans, and incorporated into the statutes two years later. This law stipulated that “nec fiant in domibus nostris superfluitates et curiositates notabiles in sculpturis et picturis et pavimentis et aliis similibus quae paupertatem nostram deformant” (“there shall not be in our houses notable superfluities and curiosities in sculptures, paintings, floors and other similar works that disfigure our poverty”). Probably the idea was to make an exception for the founder of the order, also taking into account the fact that a lavish monument dedicated to him, in addition to honoring him in a fitting manner, could have better promoted his cult, and thus benefited the order.

The problem for the Bolognese Dominicans, however, lay in the fact that there were no sculptors in the city capable of giving form to what they had in mind: the friars therefore had to widen their search to Tuscany, and here they found the right artist for their needs. The Apulian Nicola Pisano (c. 1220 - 1278/1287) had recently finished the pulpit of the Pisa Baptistery, probably someone from the Bolognese Dominicans had seen him, and the choice fell on him. There are no ancient documents that provide evidence of commissioning (although the first mention of the Ark dates back to 1265): however, since from Vasari onward the Ark of San Domenico has always been associated with Nicola Pisana, and since scholars agree on assigning the monument’s authorship to him, it has always been assumed that work began in the Pisa workshop. In any case, by 1267 the tomb was completed (although, as will be seen, its history was certainly not finished), and in a solemn ceremony, on June 5 of that year, the saint’s remains were moved there: it is known, moreover, that an assistant of Nicola Pisano, Friar Guglielmo (Pisa, c. 1235 - 1312), an architect, sculptor and member of the Dominican order, was present in Bologna during the ceremony (it is later reported that during the ceremony, the Pisan friar managed to get hold of a rib of St. Dominic’s to take to his city, and that he would confess to the theft only at the point of death). In any case, Nicola Pisano signed, in 1265, a new contract, the one for the pulpit in Siena, where he moved the following year: by 1266, therefore, the bulk of the work on the Ark of St. Dominic must have already been at an excellent stage of progress.

Of the Ark we see today, the part to be assigned to Nicola Pisano and his assistants (they worked together with him, in addition to the aforementioned Fra Guglielmo, Arnolfo di Cambio and two pupils, such Lapo and Donato, mentioned by Vasari but not known from other sources) is the sarcophagus, carved on all sides. This is the only original part of the monument that we see today in San Domenico. The sarcophagus rests on top of a green marble plinth and is closed at the top by a frame fashioned with a pattern of acanthus leaves and birds, reminiscent of the sarcophagi of classical antiquity. The narrative unfolds along all four sides of the case: the scenes are separated by four high-relief figures, those of St. Augustine, St. Ambrose, St. Jerome, and St. Gregory, or the four Doctors of the Church who are placed at the four corners (although their identification is not unanimous), while two other high-relief figures, the Madonna and Child and Christ the Redeemer, are placed in the center of the long sides, further dividing the narrative. Beginning the reading from the long side with the two scenes separated by the Virgin and Child, we see on the left the Miracle of the Resurrection of Napoleone Orsini who fell from his horse and, on the right, the Trial by Fire. The first tells of a miracle of St. Dominic, who resurrected the young Napoleon Orsini, who died as a result of a fall from his horse during a journey to Rome, while the second gives an account of an episode that took place before 1216 in Languedoc, when St. Dominic and the Albigensian heretics threw their respective books into the fire to convince the local authorities of the truth of their word: the heretics’ books burned, while by a miracle St. Dominic’s remained suspended above the fire. On the short sides are scenes with Saints Peter and Paul delivering the mission to the Dominican Order (in fact, it is said that the two Church fathers, appearing in vision to Saint Dominic, handed him a Bible and a staff) and with the Miracle of the Loaves, the latter of which took place in Bologna in 1218, when Saint Dominic, at dinner with his brothers, in want of food began to pray and two angels appeared to him and gave him bread and figs. Finally, on the other long side, we observe the scene of theApproval of St. Dominic’s rule by Pope Innocent III, a fact dating back to 1216 that is also invested with a miraculous aura (in fact, it seems that Innocent III first rejected the rule, and reconsidered after seeing St. Dominic holding up the church of St. John Lateran in a dream), and theAdhesion of Reginaldo di Orleans to the Order, which tells of the illness of the theologian Reginaldo di Orleans who, healed by St. Dominic, decided to join the preachers. All scholars agree that in ancient times the sarcophagus must have rested on caryatids, although the number of figures holding up St. Dominic’s tomb has always been a matter of debate: perhaps six or eight, and in any case three of them are preserved today at as many museums (one is at the Bargello Museum, one at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and one at the Louvre).

One of the peculiarities of these scenes consists in the fact that Nicola Pisano imagined them on the basis of the accounts of eyewitnesses who were still alive at the time when the Apulian artist had to imagine the layout of the Ark of San Domenico. The true origin of the depictions, however, is a matter of debate. Instead, all the other episodes are found in the biography of St. Dominic written by Umberto di Romans between 1256 and 1260. According to Moskowitz, however, at least a couple of the miracles, that of Napoleon Orsini and that of the loaves, would translate into images the account of an eyewitness, a nun named Cecilia Contarini, who was very young when St. Dominic was alive and was reportedly consulted by the Bolognese Dominicans. Interestingly, this scene shows an elderly woman who turns her gaze not toward the miraculous scene but in the opposite direction: for the scholar, the woman could be precisely Cecilia Contarini, depicted looking in the opposite direction from everyone else to emphasize her role as a witness to the events. Serena Romano does not think the same way, who considers erroneous the attempt to derive the tale from the nun’s testimony, due to the fact that in 1264-1265 she had not yet rendered her memoirs, and due to the fact that they were in any case ignored by the leaders of the Dominican Order, nor did they ever become part of the official hagiography, despite the fact that some episodes reported by the nun nevertheless appear in the Legendae Sancti Dominici: Cecilia Contarini had in fact been deemed an unreliable witness (according to Romano, it is also highly unlikely that the old woman depicted in the corner of the scene with the miracle of falling from a horse is a portrait of the nun: it would have been a “highly innovative” expedient, but difficult to prove).

In any case, these are miracles that took place when the saint was still alive: evidently by specific choice of the commissioners it was preferred not to include miracles that Dominic of Guzmán would have performed when dead. Indeed, it has been found that the iconographic program of the sarcophagus was conceived almost as a visual translation of the methods used by St. Dominic during his preaching: doctrine, practical examples, and miracles. As Jacopo da Varazze would explain, doctrine had an effect on the uneducated, for whom the teachings were sufficient; examples, on the other hand, were addressed to those who, once the doctrine was expounded, remained indifferent and therefore needed to see the results of the application of such theories in order to be converted; and finally, miracles were intended for the most obstinate and difficult to convince audience. It is then necessary to imagine the Ark placed in a different spot in the basilica than it is today: it was in all likelihood in a central position, near the partition that separated the space reserved for the friars from that of the laity, with the more spectacular side, the one with the scenes of the two miracles separated by the statue of Our Lady, facing the latter, since the scenes of Napoleon Orsini and the Albigensians are carved in a less complex manner than the others so that they can be well observed even from a distance. The first placement of the ark must therefore have met obvious propagandistic needs.

It was mentioned in the opening that the Ark of St. Dominic had totally innovative characters for the time in which it was made. These characters were well emphasized in Moskowitz’s volume: for example, the idea of representing several scenes in a single relief was novel. And then, although Nicola Pisano had modeled himself after Roman sarcophagi for his Pisa pulpit, the idea of integrating such a model into a modern tomb was entirely new. “The inclusion of an historiated sarcophagus,” Moskowitz wrote, “places the Ark of San Domenico within two traditions: the first, that of using ancient sarcophagi for the tombs of saints, a practice that began in the 8th century with the large-scale translation of martyrs’ relics from the catacombs to Roman basilicas; and the second, the one favored by many popes, especially in the 12th century, namely, that of choosing, as their future tomb, something similar to pagan sarcophagi, perhaps made of porphyry or decorated with triumphal symbols and themes.” Moskowitz went on to note deliberate continuities between the Ark of San Domenico and the tombs of ancient rulers, which like the Bolognese ark were imagined to be viewed from all four sides, and not leaning against a wall: a suggestion, coupled with the old-fashioned reliefs, that may have led the public of the time to make comparisons with the tombs of the ancient rulers, to conclude that the Ark, “though not explicitly based on the ancient imperial sepulchres, was seen as a kind of rival to the ideals the latter represented.” St. Dominic’s miracles and the eternity of God’s word versus, in essence, the ephemeral glory of earthly power. More eminently practical problems could also arise, however: when St. Dominic died, his remains were placed within a simple cypress chest in the church of San Niccolò delle Vigne. Following his canonization in 1234 by Gregory IX, the saint’s remains were interred in a marble sarcophagus placed in one of the side chapels of the recently completed basilica of St. Dominic (work was completed in 1228). Evidently the need had arisen to give greater visibility and, as mentioned in the opening, a more worthy burial to the founder of the order, who especially after his canonization attracted an increasing number of pilgrims to Bologna.

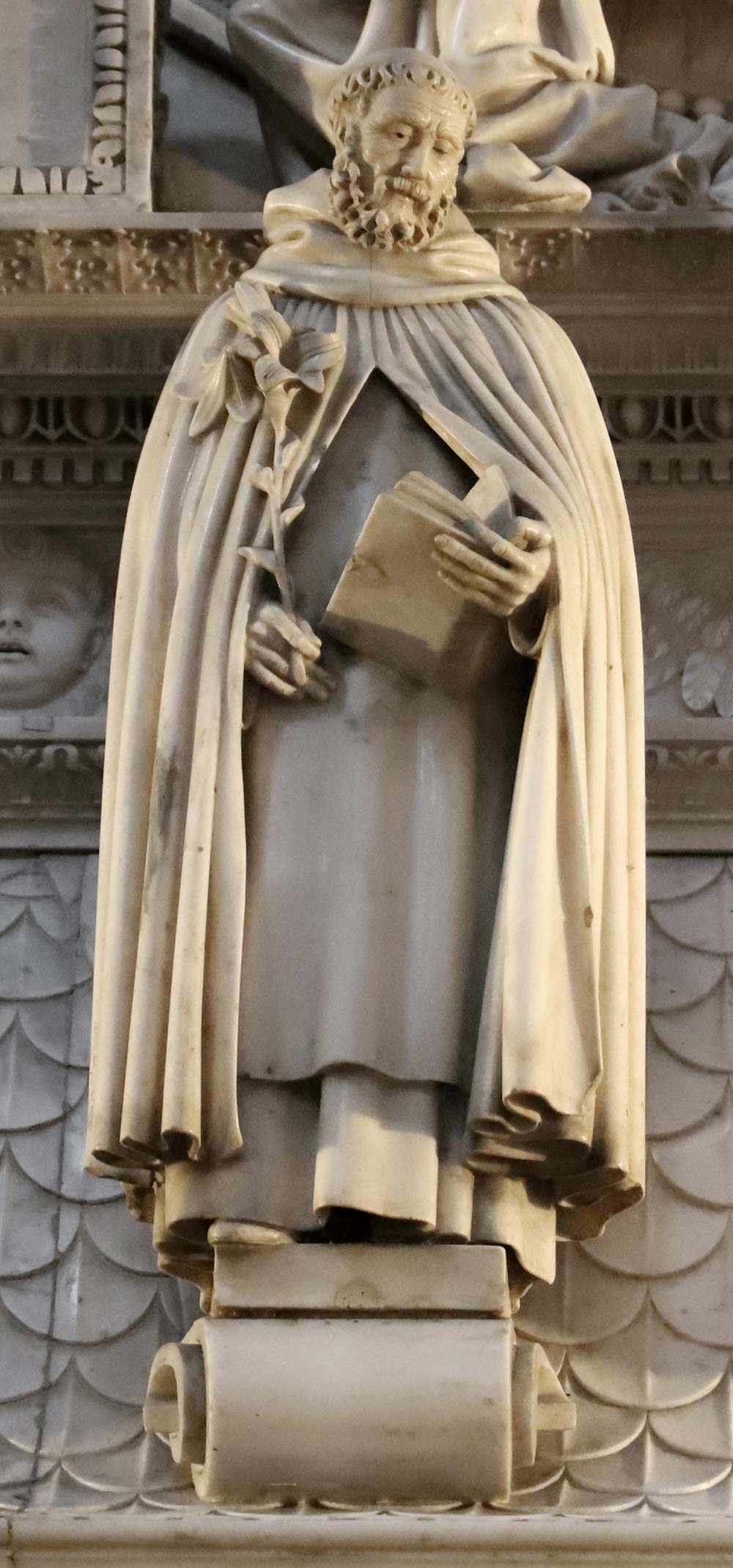

In any case, in the 15th century, the Dominicans, evidently driven by the comparison with other monuments that had been raised after the mid-14th century, such as the Ark of St. Peter Martyr or the Ark of St. Augustine, had to plan to radically renovate the monument to adapt it to the new requirements. The first step, therefore, was to raise the monument considerably in height: the Governor Protonotary Apostolic and the Regiment of the Municipality of Bologna commissioned the cymatium, curiously enough, from another great Apulian sculptor, “magistrum Nicolaum de Pulia,” namely Niccolò dell’Arca (Niccolò da Bari; c. 1435 - Bologna, 1494), whose fame was associated with the undertaking of St. Dominic to the point that the artist received his nickname for this very work. Niccolò was engaged in the execution of the cymatium between 1469 (a transcript of the contract, dated July 20 of that year and containing the iconographic program the artist was to follow, is preserved at the State Archives of Bologna) and 1473, two years longer than the contract stipulated: above the sarcophagus he arranged an elegant flake cover, surmounted by a frieze with cherubs holding two elegant volutes decorated with plant elements that join at the top to form a pinnacle beside which two putti are noted holding festoons of fruit and flowers, below which, along the two volutes, two dolphins are noted. The entire cymatium is decorated with statues: at the top, towering over the pinnacle is the globe with the figure of the Eternal Father, who in turn holds in his hand the sphere symbolizing his dominion over the world. Instead, the elements along the volutes allude to the theme of creation: the festoons symbolize the earth, the cherubs the sky, and the dolphins the water. Further down, we notice a small sarcophagus from which sprouts the figure of the dead Christ between two angels, while on the sides we see the figures of the four evangelists, also read, however, as four prophets because of their unique oriental-like attire. The representation is closed by eight statues arranged along the sides of the cymatium. They are the patron saints of Bologna: Francis, Petronius, Dominic, and Florian on the front, and Agricola, John the Baptist, Proculus, and Vitale on the back (Niccolò dell’Arca completed five out of the eight: the John the Baptist was executed in the late sixteenth century by Girolamo Cortellini, while the remaining two, Petronius and Proculus, as will be seen below, are instead the work of a very young Michelangelo).

Observing the figures sculpted by Niccolò dell’Arca and his collaborators, one witnesses, Eugenio Riccomini has written, "a progressive evolution of his language. TheEterno at the apex of the crowning, and especially the four Prophets inturbantati alla turchesca and enveloped in the rich and repeatedly replicated drapery of their mantles have a sumptuously Burgundian flavor and still recall the imposing figures of Sluter or Flemish painting, while the figures that seem more recent have the swaggering pride of Renaissance taste; the same, in short, that the secular figures in Cossa’s coeval paintings flaunt. And a couple of them look very much like contemporary portraits.“ Indeed, it seems that the figures of Saints Vitale and Agricola depict Niccolò dell’Arca himself ”dressed in the brava, in high boots, with the disheveled hair and surly frown of a man ’fantasticus et barbarus’ (thus complaining of his character, a friar of St. Dominic calls him)," and the lord of Bologna, Giovanni Bentivoglio, “in unleavened garb clad on the inside with fur and with his hand on the pommel of his sword.” Alongside these suggestions, there were then indicated, wrote Grazia Agostini, “precise links with the Marsuppini Tomb of Desiderio da Settignano in Santa Croce, datable around 1455,” although according to Cesare Gnudi the whole is “still linked to the late Gothic taste.”

The realization of the cymatium by Niccolò dell’Arca was, moreover, the result of a collaboration between the Commune and the Dominicans. It was up to the latter to choose the artist, while the city financed the project with a special tax and formed a commission to oversee the progress of the work. This was because in the 15th century the Ark of St. Dominic was no longer important only for the Dominicans, but for the whole city, having assumed the contours of a civic monument in its own right. Consequently, the “formal and programmatic density of the new design,” scholar Randi Klebanoff explained in one of his essays, “can be seen as deliberate and pregnant with meaning. In the 15th century, the focus on the saint’s body as the bearer of predominantly Dominican messages was incorporated into a scheme that reflected the diverse civic body, and modeled a utopian vision of the city as a sacred cosmos.” According to Klebanoff, the complexity of the Ark offers a composite paradigm: there one appreciates an art aimed at the audience of the faithful, pilgrims, and relic worshippers, but also a “display system of magnificence and ostentation typical of Renaissance civic culture.” And indeed the iconographic program of the cymatium conveys much more universal content than that of the sarcophagus, within which messages addressed to the city, represented by its patron saints, are also grafted. Bologna, according to Klebanoff, is depicted here as a city invested with the favor of the Eternal Father, all at a time in history when the pontiff, Paul II, was attempting to reassert papal jurisdiction over the city, but encountering strenuous opposition from Giovanni II Bentivoglio, whose considerable military might the pope feared. A diplomatic mission in 1465 stipulated that the pope would continue to recognize Bentivoglio’s authority over the city in exchange for an annual tribute of twelve thousand ducats: in this sense, the iconographic program of the ark, Klebanoff wrote, is indicative of the fact that “the vicar of God might well have demanded tribute, but God himself had seen fit to endow the city with a priceless treasure,” namely the possession of the relics of St. Dominic, raised to symbolize the favor of divinity.

Alfonso Lombardi,

Alfonso Lombardi, Alfonso Lombardi,

Alfonso Lombardi,

As mentioned, the cymatium was put in place in 1473, but Niccolò dell’Arca had not completed the work: of twenty-one statues planned, only sixteen were delivered. Three of the patron saints, one of the candelabra-holding angels at the base of the Ark, and the figure of the risen Christ were missing. The Christ was never made, the St. John the Baptist, as anticipated, was executed by Girolamo Cortellini in 1539, while the remaining statues, St. Proculus, St. Petronius (which had already been rough-hewn by Niccolò dell’Arca), and the right-hand angel are owed to the hand of the young Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, 1475 - Rome, 1564), who sculpted them between 1494 and 1495. The Florentine artist, not even 20 years old, obtained the commission through the mediation of a Bolognese nobleman, Giovanni Francesco Aldrovandi, who had taken him in after the artist had left Florence following the expulsion of the Medici, his protectors, in precisely 1494. With theAngelo reggicandelabro the artist arrived at a “logical and organic deepening,” as Enzo Carli has written, of the motifs studied in the Madonna della Scala, his early work: in fact, the artist developed his plastic sense by sculpting an angel with powerful forms, inscribed within a cubic pattern, wrapped in drapery far broader and more articulate than that of Niccolò’s Angel dell’Arca, with its “deep indentations” that emphasize the strength of the sculpture’s architectural structure, and to all this must be added an “expression of an internal energy, cooled and thus made more dramatic by the architectural discipline of the cube to which the figure is constrained.”

The same energy is felt in the figure of St. Petronius, animated by a dynamism evident in the pose of the legs, which suggest a figure in the act of moving forward in a solemn and compassionate manner. A strength that is found equally in the St. Proclus, which, although restored in the 16th century by Prospero Sogari Spani due to the fall of a beam that had damaged it, still communicates the pride and heroism of the saint, a Roman officer originally from Bologna who had suffered martyrdom during the persecutions against Christians under the Emperor Diocletian. A tension and monumentality that anticipates the more mature Michelangelo, such as that of the David (note, for example, the hand gesture of St. Proculus, which recalls that of the masterpiece now in the Accademia Gallery in Florence).

Finally, another of the great sculptors of Renaissance Bologna would later take part in the undertaking: this was Alfonso Lombardi (Ferrara, c. 1497 - Bologna, 1537), who in 1532 was in charge, commissioned by the city council, of the stele, the scabellum marmoreum, supporting the sarcophagus, carved on all four sides with theAdoration of the Magi and with four scenes from the life of St. Dominic: the birth, a scene in which he is depicted as a child while sleeping on the floor (in fact, since childhood he had refused to sleep on the bed in order to undergo discipline), the episode of selling books to make money with which to feed the poor (“I don’t want to study on leather books while people are dying of hunger,” he would have said), and Friar Guala’s vision with St. Dominic seated between Christ and Our Lady. The last image, that of the saint’s death and burial carved on the altar, was instead made in 1768 by Frenchman Jean-Baptiste Boudard. Instead, the construction of the present chapel of St. Dominic and the moving of the Ark to the place where everyone can admire it today dates back to the 17th century.

A work thus created in five main phases (Nicola Pisano, Niccolò dell’Arca, Michelangelo, Alfonso Lombardi, Jean-Baptiste Boudard), with additions and modifications that followed one another over the centuries, making the Ark of San Domenico a sort of compendium of five centuries of sculpture in Bologna, with paradigmatic examples of the developments of Italian sculpture as a whole. Within a single monument, which would later inspire several others in turn (such as the aforementioned arks of St. Peter Martyr and St. Augustine, which probably suggested the idea of updating the monument, but which inevitably could not fail to look to their Felsine counterpart), and which for these reasons has no other equal.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.